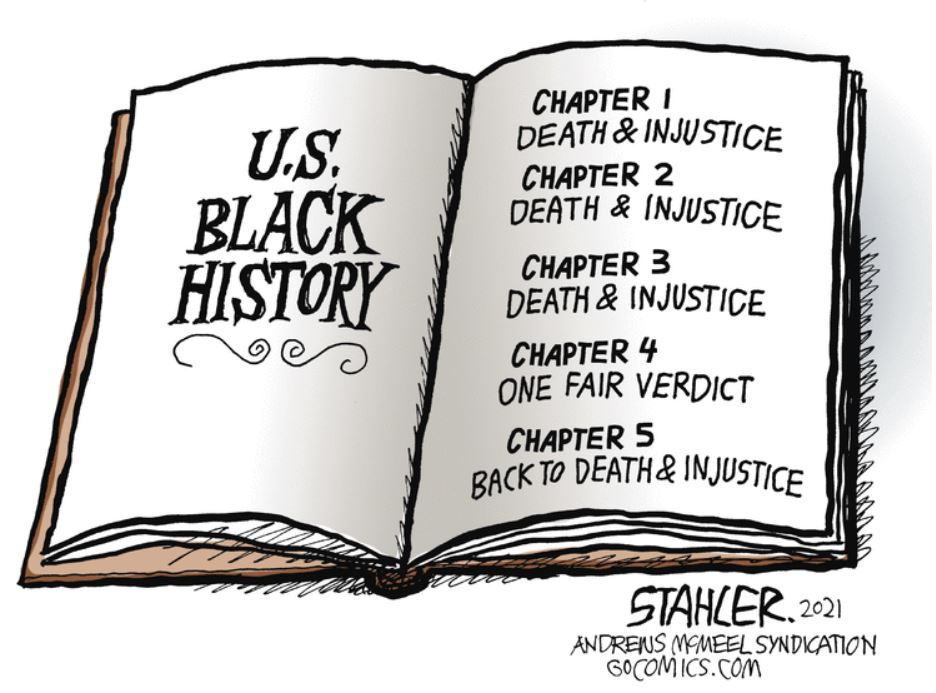

black history

past and present

HISTORY IS A PEOPLE'S MEMORY, AND WITHOUT A MEMORY, MAN IS DEMOTED TO THE

LOWER ANIMALS.

MALCOLM X

FEBRUARY 2023

THE RT. HON. MARCUS GARVEY: "A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots."

The American Negro never can be blamed for his racial animosities

- he is only reacting to 400 years of the conscious racism of the American whites.

Malcolm X

recommended readings

*for those who want the to know the truth*

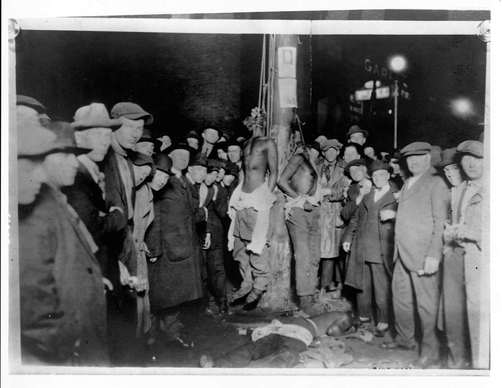

**RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA

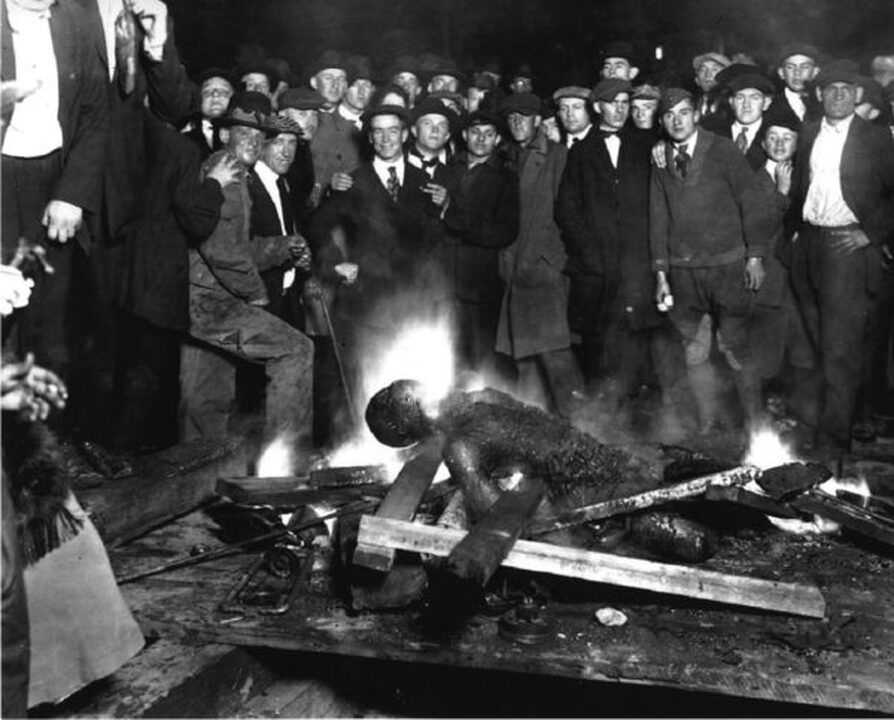

THE REPORT, RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA, DOCUMENTS MORE THAN 2,000 BLACK VICTIMS OF RACIAL TERROR LYNCHINGS KILLED BETWEEN THE END OF THE CIVIL WAR IN 1865 AND THE COLLAPSE OF FEDERAL EFFORTS TO PROTECT THE LIVES AND VOTING RIGHTS OF BLACK AMERICANS IN 1876.

*the apocalypse of settler colonialism by dr. gerald horne

*slavery by another name by douglas a. blackman

*THEY CAME BEFORE COLUMBUS

THE AFRICAN PRESENCE IN ANCIENT AMERICA

BY IVAN VAN SERTIMA

*AMERICAN SLAVE COAST - HISTORY OF THE SLAVE-BREEDING INDUSTRY

BY NED AND CONSTANCE SUBLETTE

*EBONY AND IVY - RACE, SLAVERY, AND THE TROUBLED HISTORY OF AMERICA'S UNIVERSITIES

BY CRAIG STEVEN WILDER

*COMPLICITY: HOW THE NORTH PROMOTED, PROLONGED, AND PROFITED FROM SLAVERY

BY ANNE FARROW

*AMERICA'S ORIGINAL SIN

BY JIM WALLIS

*THE COUNTER REVOLUTION OF 1776

BY GERALD HORNE

*WHITE RAGE" BY CAROL ANDERSON, PHD.

*Stark Mad Abolitionists by robert k. sutton

articles of interest

*HOWARD THURMAN'S "FASCIST MASQUERADE": THE BLACK THINKER WHO SAW THIS COMING, 75 YEARS AGO(ARTICLE BELOW)

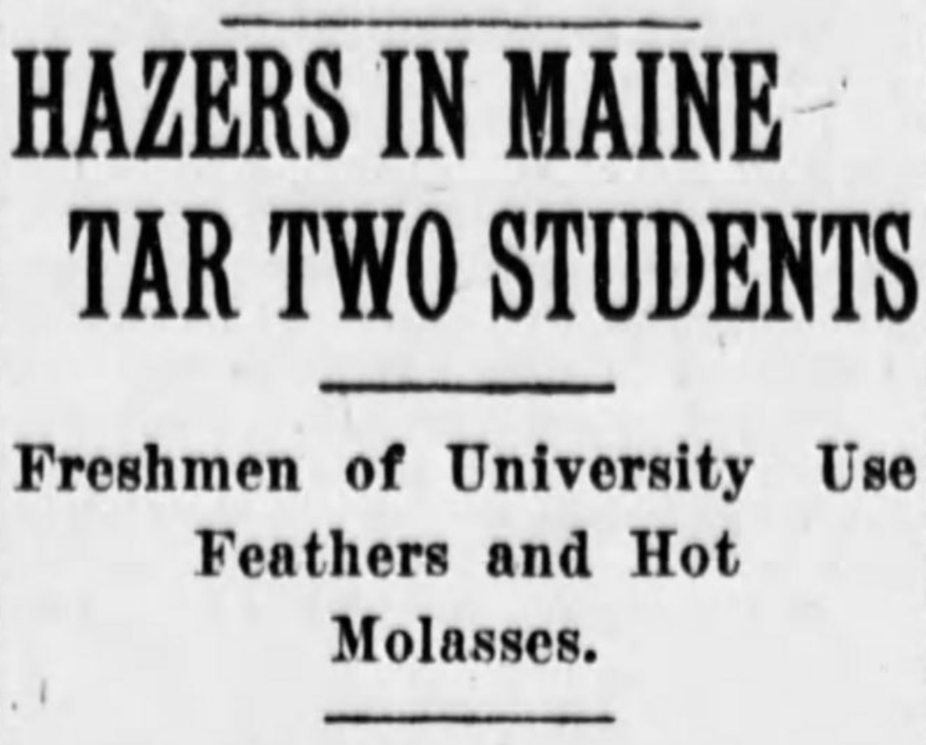

*THE HIDDEN STORY OF WHEN TWO BLACK COLLEGE STUDENTS WERE TARRED AND FEATHERED

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*SLAVE-BUILT INFRASTRUCTURE STILL CREATES WEALTH IN US, SUGGESTING REPARATIONS SHOULD COVER PAST HARMS AND CURRENT VALUE OF SLAVERY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*He fought for Black voting rights after the Civil War. He was almost killed for it.

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Feminism, flour bombs and the first black Miss World

(ARTICLE BELOW)

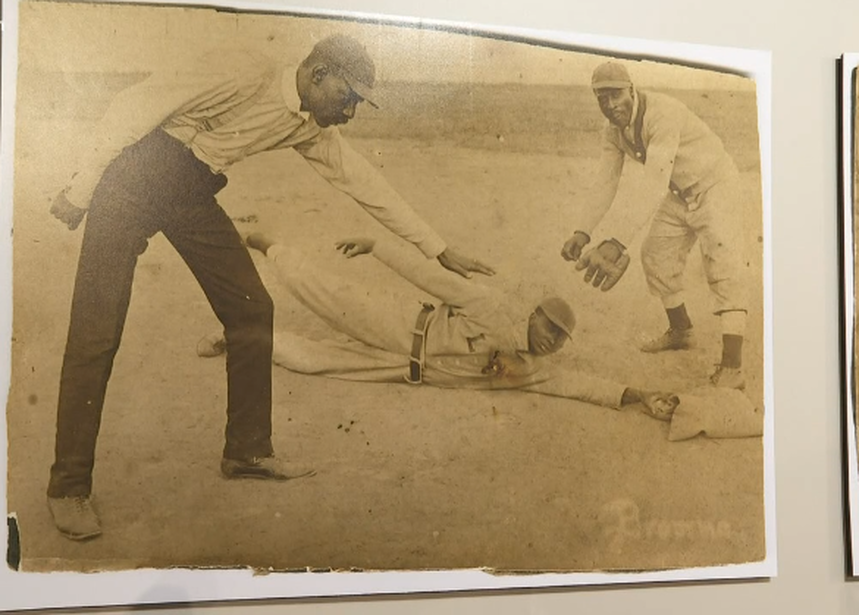

*Curator Uncovers Black Baseball Team That Dominated Before Integration of Sport

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*NEXT FORD-CLASS CARRIER TO BE NAMED AFTER PEARL HARBOR HERO DORIS MILLER

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*GI BILL OPENED DOORS TO COLLEGE FOR MANY VETS, BUT POLITICIANS CREATED A SEPARATE ONE FOR BLACKS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A rural town confronts its buried history of mass killings of black Americans

(ARTICLE BELOW)

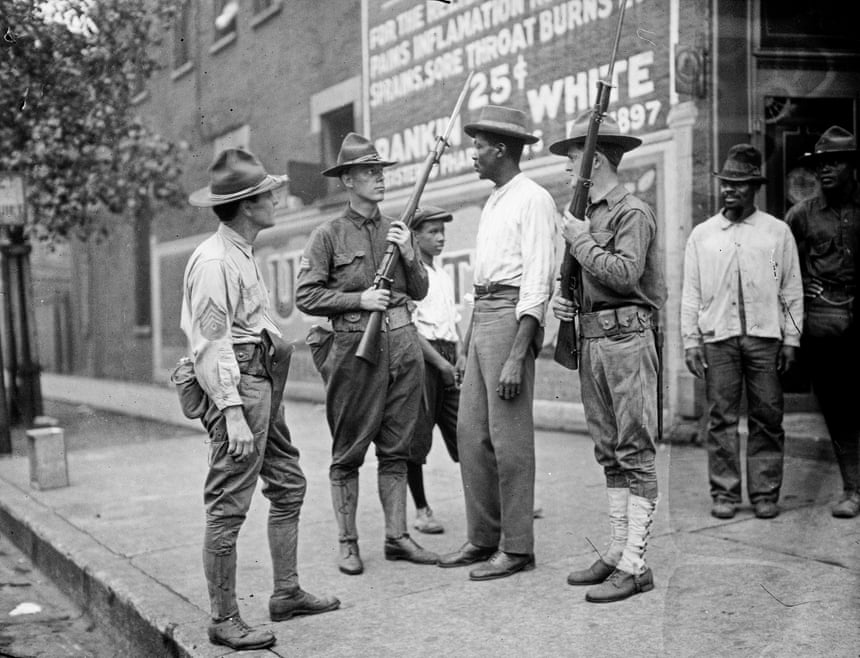

*Red Summer, 100 Years Later: When the White Mob Was Unleashed on Black America

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*6 Important Things You May Not Know About Juneteenth — But Should

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Marsha P. Johnson: Transgender hero of Stonewall riots finally gets her due

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*GROUNDBREAKING WORLD WAR II UNIT OF BLACK WOMEN HONORED DECADES AFTER THEIR SERVICE(ARTICLE BELOW)

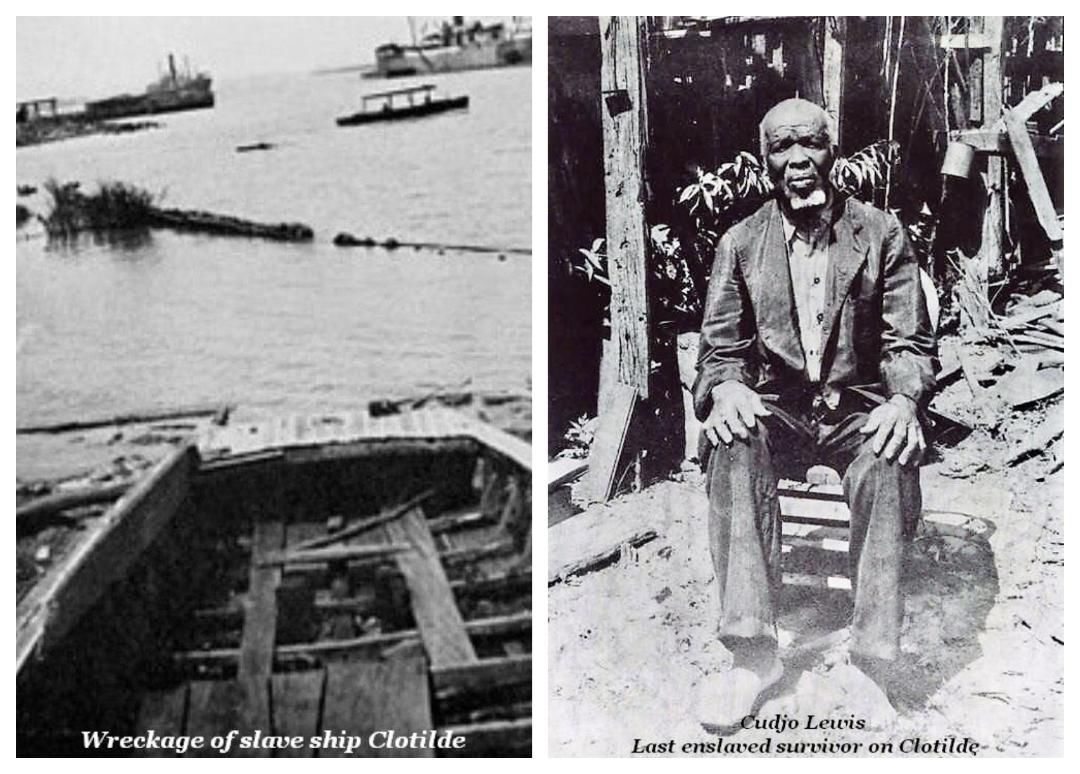

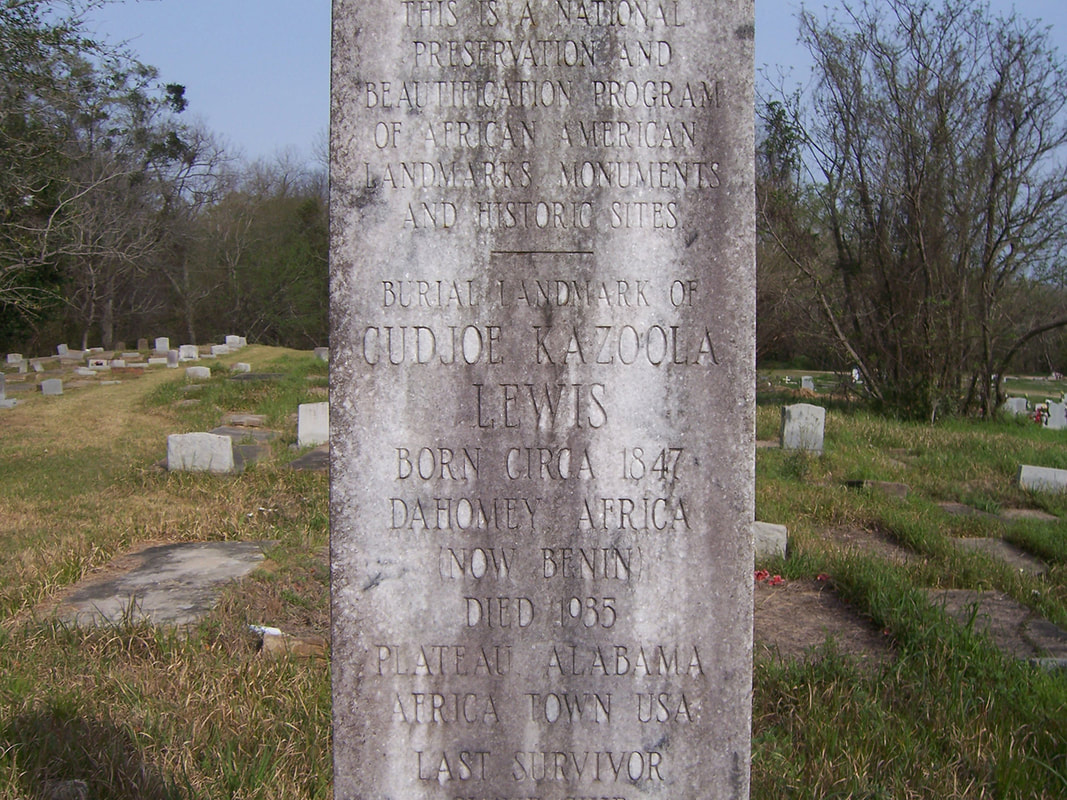

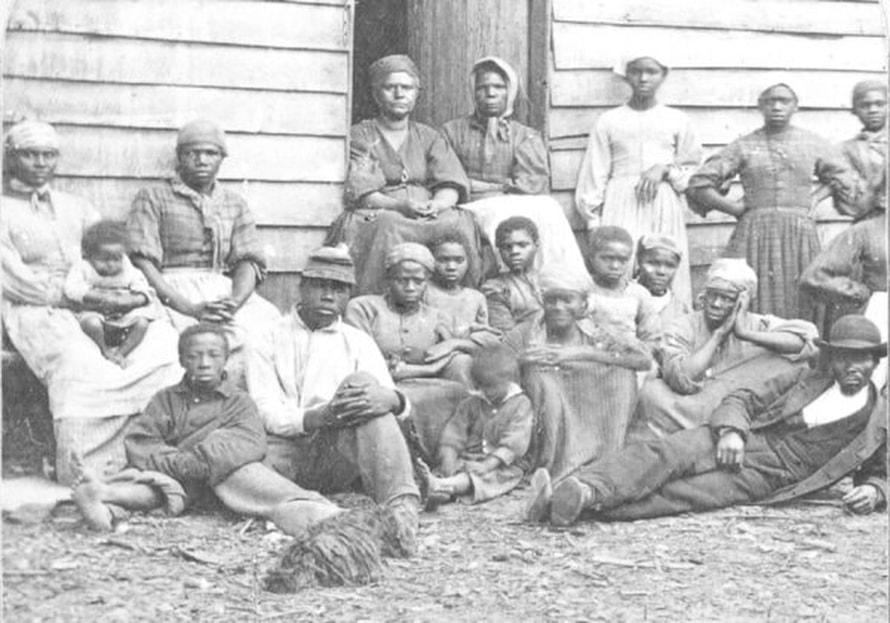

*SLAVERY: LAST KNOWN US SLAVE SHIP FOUND IN ALABAMA

(ARTICLE BELOW)

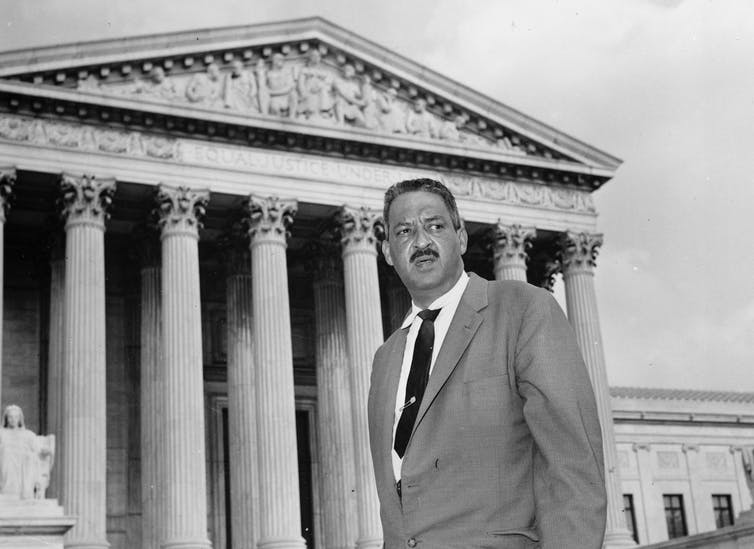

*The Brown V. Board Of Education Case Didn't Start How You Think It Did

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Mary Elizabeth Bowser: Spy of the Confederate White House

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Researchers, Descendents Seek Recognition for Africans Who Were Central to the Success of England’s First Settlement In U.S. (ARTICLE BELOW)

*HERE ARE 9 MLK QUOTES YOU WON’T HEAR MAINSTREAM MEDIA CITE TODAY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

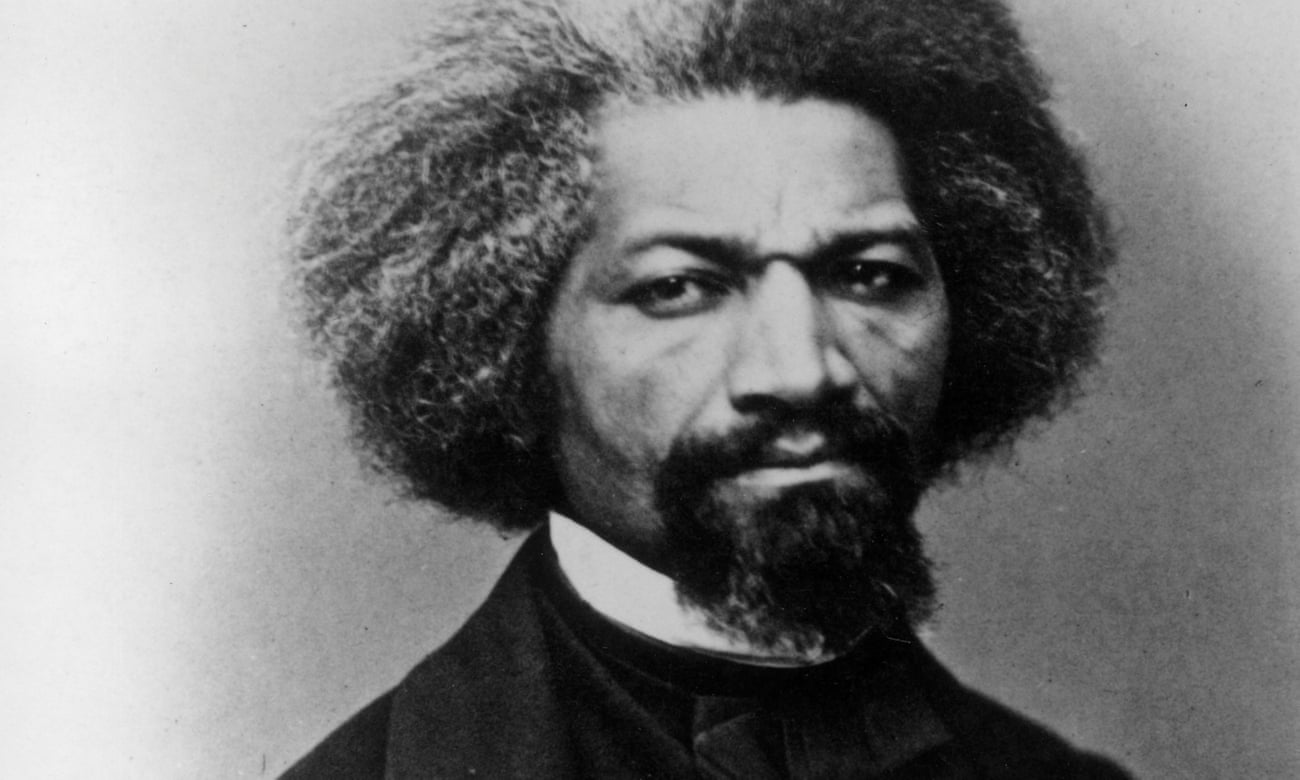

*FREDERICK DOUGLASS: PROPHET OF FREEDOM REVIEW: A MONUMENTAL BIOGRAPHY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Coard: Tuskegee syphilis study’s Black ‘guinea pigs’

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WHEN WHITE MALE RAPE WAS LEGAL

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*U.S., historian battle over unsealing records on 1946 lynching

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Quakers to honor slaves buried on their land in Bucks County

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*'Our history is getting erased': the biggest threat to Sandy Island's Gullah is not hurricanes

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Meet Haiti’s Founding Father — His Black Revolution Was Too Radical for Thomas Jefferson(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A MASS GRAVE OF PRISON LABORERS IN TEXAS SHOULD BE RESPECTED, NOT PAVED OVER

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Legacy of Slavery, Segregation Impacts Debate on Talbot Boys Statue In Maryland

(EXCERPT BELOW)

*Tennessee reopens civil rights cold case from 1940

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Coard: Last slave ship docked 158 years ago

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Burial Site of Nearly 5,000 Newly Freed Blacks Covered by Playground to Get Memorial

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*When the Fourth of July Was a Black Holiday

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*White Politicians Have Been Coercing African-Americans to Vote Since Before the Civil Rights Era(ARTICLE BELOW)

*York plans statue of African-American

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The Army’s First Black Nurses Were Relegated to Caring for Nazi Prisoners of War

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The Last Slave Ship Survivor Gave an Interview in the 1930s. It Just Surfaced

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*How African-Americans disappeared from the Kentucky Derby

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Ida B Wells: the unsung heroine of the civil rights movement

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE NATIONAL MEMORIAL FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*This massacre of black soldiers during the Civil War is reason enough to bring down the Confederate statues(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Women’s Empowerment Was a Big Deal In African Societies, Before Christianity and Islam(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Coard: Ota Benga, an African, caged in American Zoos(ARTICLE BELOW)

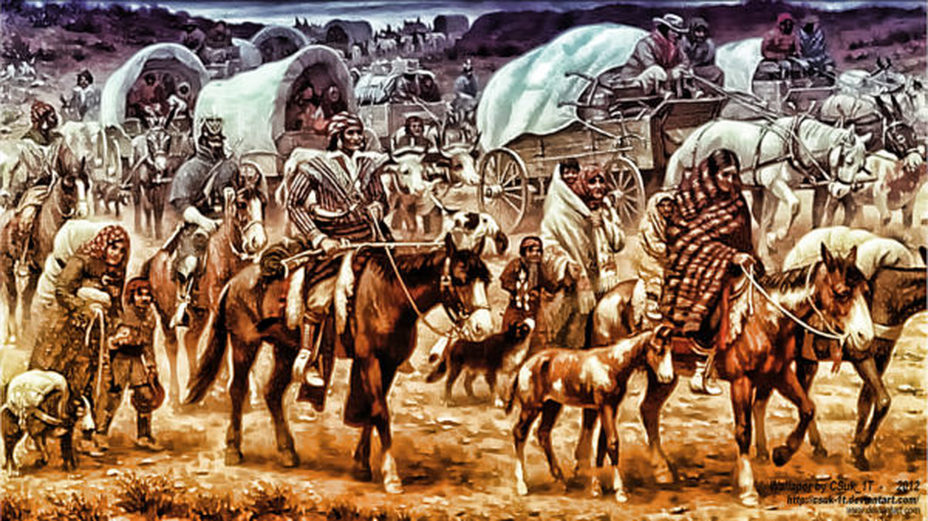

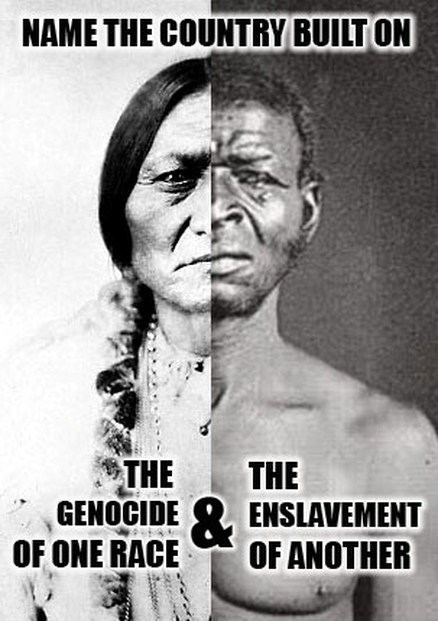

*Enslaved Black People: The Part of the Trail of Tears Narrative No One Told You About

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE BLACK WOMAN WHO RESISTED SEGREGATION IN CANADA WILL NOW APPEAR ON ITS CURRENCY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*J. Ernest Wilkins Jr.: ‘Superb Mathematician’ Broke Barriers at Dawn of Atomic Age

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Their forefathers were enslaved. Now, 400 years later, their children will be landowners

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*COARD: GEORGE WASHINGTON'S TEETH NOT FROM WOOD BUT SLAVES(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Tony McGee got kicked out of Wyoming with the Black 14 but still made it to the Super Bowl

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The Secret History of the White House’s Kitchen Slaves(ARTICLE BELOW)

*'Still fighting': Africatown, site of last US slave shipment, sues over pollution(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The DNA of Iceland's First Known Black Man, Recreated from His Living Descendants

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The Myth of Black Confederates

And the rise of fake racial tolerance(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A CENTURY LATER, A LITTLE-KNOWN MASS HANGING OF BLACK SOLDIERS STILL HAUNTS US(ARTICLE BELOW)

*VROOM VROOM: THE SHORT, BUT POIGNANT HISTORY OF BLACK AMERICANS IN THE WORLD OF NASCAR(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ROY MOORE: ACCEPTANCE OF PEDOPHILLIA IN THE SOUTH IS A LEGACY OF SLAVERY(excerpt below)

*HOW AFRICAN AMERICAN WWII VETERANS WERE SCORNED BY THE G.I. BILL(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE TIRELESS ABOLITIONIST NOBODY EVER HEARD OF(ARTICLE BELOW)

*IGNORANCE EXTOLLED: FORCED ANTHEM ADHERENCE ANTITHETICAL TO JUSTICE(ARTICLE BELOW)

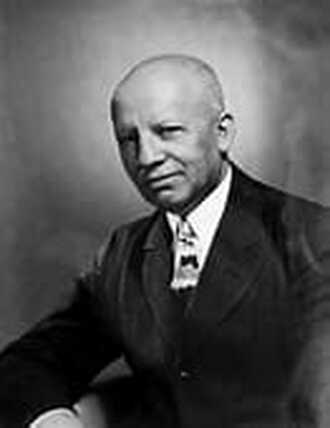

the father of black history

Carter G. Woodson was the second African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard, after W.E.B. Du Bois. Known as the "Father of Black History," Woodson dedicated his career to the field of African American history and lobbied extensively to establish Black History Month as a nationwide institution.

Early Life

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on December 19, 1875, in New Canton, Virginia, to Anna Eliza Riddle Woodson and James Woodson. The fourth of seven children, young Woodson worked as a sharecropper and a miner to help his family. He began high school in his late teens and proved to be an excellent student, completing a four-year course of study in less than two years.

Associations and Publications

In 1915, Woodson helped found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (later named the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), which had the goal of placing African American historical contributions front and center.

Early Life

Carter Godwin Woodson was born on December 19, 1875, in New Canton, Virginia, to Anna Eliza Riddle Woodson and James Woodson. The fourth of seven children, young Woodson worked as a sharecropper and a miner to help his family. He began high school in his late teens and proved to be an excellent student, completing a four-year course of study in less than two years.

Associations and Publications

In 1915, Woodson helped found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (later named the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), which had the goal of placing African American historical contributions front and center.

america!!!

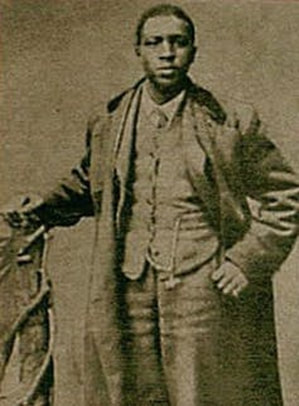

How Stephen Smith, once the richest Black man in U.S., used his wealth to free thousands of African Americans

Stephen Nartey - Face2FaceAfrica

2/6/2023

One of his notable legacies is getting 15,000 people of African descent to move to Canada after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. His commitment to fighting slavery stemmed from the fact that he was born into slavery.

Abolitionist Stephen Smith became aware of his status when he was separated from his mother at the age of five and given out to Pennsylvanian businessman Thomas Boude as an indentured servant. Boude, who was a former revolutionary war officer from Lancaster County, placed Smith in charge of his lumber business, according to Stephen Smith House.

His mother, Nancy Smith, was a slave so she had no choice concerning his fate. But when Smith was 21, he raised $50 to purchase his freedom on January 3, 1816. Smith was born in 1725 in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. He married Harriet Lee on November 17, 1816, while she was still working as a servant in the Jonathan Mifflin home.

He ventured into the lumber business shortly after he gained his freedom. He operated his business in Columbia, Pennsylvania. He expanded his business when he became successful. He partnered with William Whipper in 1830 as part of his vision to establish a global conglomerate with the lumber business as the central focus.

Smith and Whipper ran a lucrative business and soon diversified into coal, real estate, railroad cars as well as other investments in the stock market. Smith became known as the richest Black man in America. As part of giving back to society, Smith and Whipper decided to use their wealth to fight slavery. His efforts earned him the Chairman of the African American Abolitionist Organization in 1830.

In 1831, he was ordained in the Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church on South Fifth Street, Columbia. The white community began sabotaging his business when they realized the success of his business. In 1835 a mob of whites destroyed his office including his documents and records.

Instead of being deterred and cowed into submission, Smith prioritized his agenda of combating slavery. He purchased a safe house where he held meetings with the black community. He helped many enslaved Africans to escape from Maryland to Canada.

He kicked against a policy instituted by the American Colonisation Society and demonstrated his stiff resistance by leading free blacks in Columbia in a public meeting in 1831. He partnered with other abolitionists such as David Ruffles, John Peck, Abraham Shadd and John B. Cash.

Though he was the largest shareholder of the Columbia Bank, the color of his skin made it impossible for them to name him as the President of the bank. The power he had was to name a white man in his stead. His dream was that the African-American community would be empowered and free someday.

Smith died in 1873.

Abolitionist Stephen Smith became aware of his status when he was separated from his mother at the age of five and given out to Pennsylvanian businessman Thomas Boude as an indentured servant. Boude, who was a former revolutionary war officer from Lancaster County, placed Smith in charge of his lumber business, according to Stephen Smith House.

His mother, Nancy Smith, was a slave so she had no choice concerning his fate. But when Smith was 21, he raised $50 to purchase his freedom on January 3, 1816. Smith was born in 1725 in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. He married Harriet Lee on November 17, 1816, while she was still working as a servant in the Jonathan Mifflin home.

He ventured into the lumber business shortly after he gained his freedom. He operated his business in Columbia, Pennsylvania. He expanded his business when he became successful. He partnered with William Whipper in 1830 as part of his vision to establish a global conglomerate with the lumber business as the central focus.

Smith and Whipper ran a lucrative business and soon diversified into coal, real estate, railroad cars as well as other investments in the stock market. Smith became known as the richest Black man in America. As part of giving back to society, Smith and Whipper decided to use their wealth to fight slavery. His efforts earned him the Chairman of the African American Abolitionist Organization in 1830.

In 1831, he was ordained in the Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church on South Fifth Street, Columbia. The white community began sabotaging his business when they realized the success of his business. In 1835 a mob of whites destroyed his office including his documents and records.

Instead of being deterred and cowed into submission, Smith prioritized his agenda of combating slavery. He purchased a safe house where he held meetings with the black community. He helped many enslaved Africans to escape from Maryland to Canada.

He kicked against a policy instituted by the American Colonisation Society and demonstrated his stiff resistance by leading free blacks in Columbia in a public meeting in 1831. He partnered with other abolitionists such as David Ruffles, John Peck, Abraham Shadd and John B. Cash.

Though he was the largest shareholder of the Columbia Bank, the color of his skin made it impossible for them to name him as the President of the bank. The power he had was to name a white man in his stead. His dream was that the African-American community would be empowered and free someday.

Smith died in 1873.

Howard Thurman's "Fascist Masquerade": The Black thinker who saw this coming, 75 years ago

At the end of World War II, pioneering religious thinker Howard Thurman saw fascism coming to Christian America

By PETER EISENSTADT - salon

FEBRUARY 13, 2021 5:00PM (UTC)

...The problem with calling anyone or any movement fascist is that "fascism" is likely the slipperiest term in our political vocabulary. And there is the further problem that there has never been a large avowedly fascist movement in the United States. But if we look at the perpetrators of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol — with their Confederate flags, their claims to be religious warriors for Jesus, their beliefs that those opposing them were traitors — we see elements that have been common in descriptions of American fascism for a century. In the words of one commentator on the subject:

These organizations exploit the active and latent prejudices that the average American has against the non-white races on the one hand and against the Jewish people on the other. They make it possible for a creative rationalization to provide a cloak for group hatreds which can be objectified as true Christianity or true Americanism. In other words, they provide for a legitimizing of sadistic and demonical impulses of which, under normal circumstances they might be ashamed. To appeal to anti-Negro sentiment in many sections, communities and among many groups is a "natural" for the would-be demagogue. It is sure fire.

The word "Negro" is a likely giveaway, but this is not a reflection on recent events. It was written by the African American religious thinker, Howard Thurman (1899–1981), a pioneering advocate of radical nonviolence, an inspiration to the Black Freedom Struggle, a mentor to such civil rights pioneers as James Farmer, Pauli Murray and Martin Luther King Jr., and published in a 1946 essay titled "The Fascist Masquerade." The essay is one of Thurman's most urgent yet enduring political works. Its inspiration was Thurman's sense that the United States, shortly after the end of World War II, was at a crossroads. Either the post-war period would see the furthering of the tentative wartime gains by Black Americans for full citizenship, or it would see those aspirations crushed, as had happened so many times before, by a ferocious pushback by the maintainers and abetters of what Thurman called "the will to segregation."

Thurman, to be sure, was an optimist. In 1944 he left a comfortable position as dean of chapel at Howard University to co-found a small, fledgling congregation in San Francisco, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, one of the first churches in the U.S. intentionally organized on an interracial and interdenominational basis. At the same time, he was a realist. He wrote in 1943 that the war against Japan "has given excellent justification for the expression of the prejudices against non-white peoples just under the surface of the American consciousness." In his wartime travels he found "the picture is the same everywhere — sporadic outbursts of violence, meanness, murder, and bloodshed." Black Americans were angry, and many whites were furious that they were no longer hiding their anger. The United States had to choose between democracy and fascism, and for Thurman the outcome was uncertain. But he was sure that American fascism would hide behind a homegrown vocabulary drawn from a toxic and intolerant Christianity and ultra-Americanism, disguising their real beliefs and intents. This was the fascist masquerade.

For Thurman, the key to the ideology of fascism was the belief in inequality, the belief that the world was invidiously divided between the haves and have-nots, those favored, whom the state would help, and those out of favor, to whom the state disclaimed and denied any responsibility. Fascism was a worldview that built upon all existing inequalities; whether of race, class, nationality or what have you, and consciously tried to exacerbate those differences. And that was how business elites and the common racial prejudices of most white Americans could find common ground in fascism.

By 1946 Thurman was very concerned by the growing strength of anti-union sentiment in post-war America. Among the fascist organizations he considered in detail in his essay was the now quite obscure Christian American Association. Based in Houston, it was a racist, anti-labor and anti-Semitic organization whose one lasting contribution to American history was to popularize the term "right to work" while working to help enact the nation's first such laws, banning the "closed" or union shop, in Arkansas and Florida, in 1944. (One reason for such laws, the organization stated, was so "white men and women" would not be forced to work with "black African apes.") Thurman thought the Christian American Association had the perfect name for an American fascist organization.

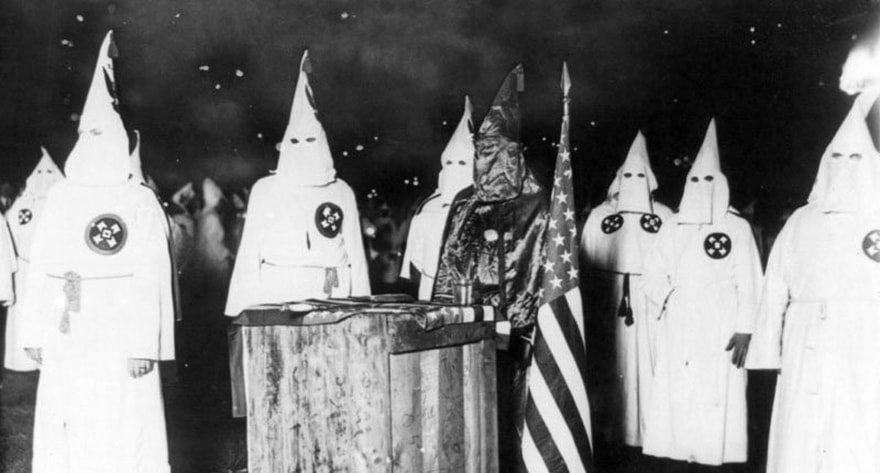

Another, much better-known group Thurman wrote about was the Ku Klux Klan, which some observers had labeled fascist even before Benito Mussolini seized power in Italy in 1922. The Klan, in its various incarnations, had an exceptional longevity whereas, as Thurman wrote, most "hate organizations spring up, flourish for a season, disappear, and reappear in another form." The organizational form of such groups was less important than their continuing appeal, he added, noting that "an important part of the menace of fascism is its property as a catalyst," how its appeal "crystallizes moods, attitudes, and fears already in solution."

Thurman's enduring insight was that was a mistake to see hate organizations like the Klan as somehow outside the political mainstream. They were merely the far edge of a society that tolerated inequalities of all kinds as part of its civic and political life. To counter hate organizations it was "no answer to say" that hate organizations represent "a false interpretation of Christianity" or America. They represented the church and the state only too well. Traditional Protestant Christianity, he thought, with its ironclad division between the saved and the damned, provided the template for all the invidious distinctions that underlined American racism and fascism. As for American democracy, in the gap between the soaring promises of the Declaration of Independence and the uglier realities was a space in which economic and social inequalities could fester and become accepted as natural or even essential parts of American society and religion. This allowed, Thurman wrote, "the various hate-inspired groups to establish squatter's rights" in our basic institutions.

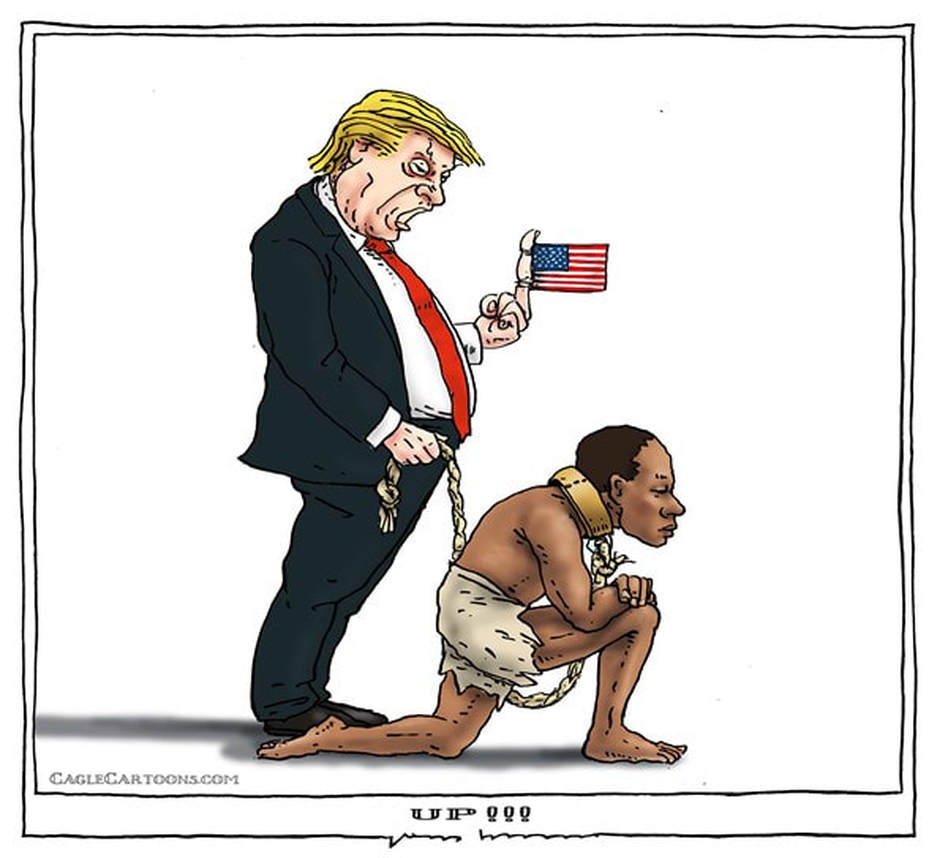

What would Thurman have to say about Donald Trump and the Capitol insurrection? Such retrospective ventriloquizing is always dangerous, but it is fair to say that he would have been appalled, and would have been dismayed that for all the changes in the United States since 1946, the descendants of the Christian American Association are still engaged in a version of the same old Christian American fascist masquerade.

For Thurman, the most pressing danger of the fascist masquerade was its protean quality, its myriad guises and disguises. It was all too easy to become inured to its prevalence. It is not enough to oppose the KKK or their latter-day descendants such as the Proud Boys. We must look to the ways inequalities between persons are tolerated in our society as a whole. We must look to ourselves, and examine the ways we tolerate inequalities of all kinds in our own lives and politics. Thurman argued that we must "rely upon the guarantee of God in whom all life and all of the great potentials of mind and spirit are grounded. Such a position establishes the infinite worth of all individuals and denies that for which fascism stands."

We may see this struggle in more secular terms than Thurman, and we may believe that implementing a society based on the "infinite worth of all individuals," where no one is a means to another person's ends, is a utopian dream. At the same time, we need to confront the reality that almost 75 years after Thurman wrote his essay, the fascist masquerade, with its facades, its lies, its true believers and silent supporters, and its chilling willingness to resort to violence, is still very much with us, and seems to be growing stronger, not weaker. And as Thurman wrote in 1946, in 2021 we still stand at a crossroads, and still face the same stark choice: Democracy or fascism.

These organizations exploit the active and latent prejudices that the average American has against the non-white races on the one hand and against the Jewish people on the other. They make it possible for a creative rationalization to provide a cloak for group hatreds which can be objectified as true Christianity or true Americanism. In other words, they provide for a legitimizing of sadistic and demonical impulses of which, under normal circumstances they might be ashamed. To appeal to anti-Negro sentiment in many sections, communities and among many groups is a "natural" for the would-be demagogue. It is sure fire.

The word "Negro" is a likely giveaway, but this is not a reflection on recent events. It was written by the African American religious thinker, Howard Thurman (1899–1981), a pioneering advocate of radical nonviolence, an inspiration to the Black Freedom Struggle, a mentor to such civil rights pioneers as James Farmer, Pauli Murray and Martin Luther King Jr., and published in a 1946 essay titled "The Fascist Masquerade." The essay is one of Thurman's most urgent yet enduring political works. Its inspiration was Thurman's sense that the United States, shortly after the end of World War II, was at a crossroads. Either the post-war period would see the furthering of the tentative wartime gains by Black Americans for full citizenship, or it would see those aspirations crushed, as had happened so many times before, by a ferocious pushback by the maintainers and abetters of what Thurman called "the will to segregation."

Thurman, to be sure, was an optimist. In 1944 he left a comfortable position as dean of chapel at Howard University to co-found a small, fledgling congregation in San Francisco, the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, one of the first churches in the U.S. intentionally organized on an interracial and interdenominational basis. At the same time, he was a realist. He wrote in 1943 that the war against Japan "has given excellent justification for the expression of the prejudices against non-white peoples just under the surface of the American consciousness." In his wartime travels he found "the picture is the same everywhere — sporadic outbursts of violence, meanness, murder, and bloodshed." Black Americans were angry, and many whites were furious that they were no longer hiding their anger. The United States had to choose between democracy and fascism, and for Thurman the outcome was uncertain. But he was sure that American fascism would hide behind a homegrown vocabulary drawn from a toxic and intolerant Christianity and ultra-Americanism, disguising their real beliefs and intents. This was the fascist masquerade.

For Thurman, the key to the ideology of fascism was the belief in inequality, the belief that the world was invidiously divided between the haves and have-nots, those favored, whom the state would help, and those out of favor, to whom the state disclaimed and denied any responsibility. Fascism was a worldview that built upon all existing inequalities; whether of race, class, nationality or what have you, and consciously tried to exacerbate those differences. And that was how business elites and the common racial prejudices of most white Americans could find common ground in fascism.

By 1946 Thurman was very concerned by the growing strength of anti-union sentiment in post-war America. Among the fascist organizations he considered in detail in his essay was the now quite obscure Christian American Association. Based in Houston, it was a racist, anti-labor and anti-Semitic organization whose one lasting contribution to American history was to popularize the term "right to work" while working to help enact the nation's first such laws, banning the "closed" or union shop, in Arkansas and Florida, in 1944. (One reason for such laws, the organization stated, was so "white men and women" would not be forced to work with "black African apes.") Thurman thought the Christian American Association had the perfect name for an American fascist organization.

Another, much better-known group Thurman wrote about was the Ku Klux Klan, which some observers had labeled fascist even before Benito Mussolini seized power in Italy in 1922. The Klan, in its various incarnations, had an exceptional longevity whereas, as Thurman wrote, most "hate organizations spring up, flourish for a season, disappear, and reappear in another form." The organizational form of such groups was less important than their continuing appeal, he added, noting that "an important part of the menace of fascism is its property as a catalyst," how its appeal "crystallizes moods, attitudes, and fears already in solution."

Thurman's enduring insight was that was a mistake to see hate organizations like the Klan as somehow outside the political mainstream. They were merely the far edge of a society that tolerated inequalities of all kinds as part of its civic and political life. To counter hate organizations it was "no answer to say" that hate organizations represent "a false interpretation of Christianity" or America. They represented the church and the state only too well. Traditional Protestant Christianity, he thought, with its ironclad division between the saved and the damned, provided the template for all the invidious distinctions that underlined American racism and fascism. As for American democracy, in the gap between the soaring promises of the Declaration of Independence and the uglier realities was a space in which economic and social inequalities could fester and become accepted as natural or even essential parts of American society and religion. This allowed, Thurman wrote, "the various hate-inspired groups to establish squatter's rights" in our basic institutions.

What would Thurman have to say about Donald Trump and the Capitol insurrection? Such retrospective ventriloquizing is always dangerous, but it is fair to say that he would have been appalled, and would have been dismayed that for all the changes in the United States since 1946, the descendants of the Christian American Association are still engaged in a version of the same old Christian American fascist masquerade.

For Thurman, the most pressing danger of the fascist masquerade was its protean quality, its myriad guises and disguises. It was all too easy to become inured to its prevalence. It is not enough to oppose the KKK or their latter-day descendants such as the Proud Boys. We must look to the ways inequalities between persons are tolerated in our society as a whole. We must look to ourselves, and examine the ways we tolerate inequalities of all kinds in our own lives and politics. Thurman argued that we must "rely upon the guarantee of God in whom all life and all of the great potentials of mind and spirit are grounded. Such a position establishes the infinite worth of all individuals and denies that for which fascism stands."

We may see this struggle in more secular terms than Thurman, and we may believe that implementing a society based on the "infinite worth of all individuals," where no one is a means to another person's ends, is a utopian dream. At the same time, we need to confront the reality that almost 75 years after Thurman wrote his essay, the fascist masquerade, with its facades, its lies, its true believers and silent supporters, and its chilling willingness to resort to violence, is still very much with us, and seems to be growing stronger, not weaker. And as Thurman wrote in 1946, in 2021 we still stand at a crossroads, and still face the same stark choice: Democracy or fascism.

The hidden story of when two Black college students were tarred and feathered

the conversation

February 8, 2021 8.37am EST

One cold April night in 1919, at around 2 a.m., a mob of 60 rowdy white students at the University of Maine surrounded the dorm room of Samuel and Roger Courtney in Hannibal Hamlin Hall. The mob planned to attack the two Black brothers from Boston in retaliation for what a newspaper article described at the time as their “domineering manner and ill temper.” The brothers were just two among what yearbooks show could not have been more than a dozen Black University of Maine students at the time.

While no first-person accounts or university records of the incident are known to remain, newspaper clippings and photographs from a former student’s scrapbook help fill in the details.

Although outnumbered, the Courtney brothers escaped. They knocked three freshmen attackers out cold in the process. Soon a mob of hundreds of students and community members formed to finish what the freshmen had started. The mob captured the brothers and led them about four miles back to campus with horse halters around their necks.

Before a growing crowd at the livestock-viewing pavilion, members of the mob held down Samuel and Roger as their heads were shaved and their bodies stripped naked in the near-freezing weather. They were forced to slop each other with hot molasses. The mob then covered them with feathers from their dorm room pillows. The victims and bystanders cried out for the mob to stop but to no avail. Local police, alerted hours earlier, arrived only after the incident ended. No arrests were made.

Incidents of tarring and feathering as a form of public torture can be found throughout American history, from colonial times onward. In nearby Ellsworth, Maine, a Know Nothing mob, seen by some as a forerunner to the KKK, tarred and feathered Jesuit priest Father John Bapst in 1851. Especially leading into World War I, this method of vigilantism continued to be used by the KKK and other groups against Black Americans, immigrants and labor organizers, especially in the South and West. As with the Courtney brothers incident, substitutions like molasses or milkweed were made based on what was readily available. Although rarely fatal, victims of tarring and feathering attacks were not only humiliated by being held down, shaved, stripped naked and covered in a boiled sticky substance and feathers, but their skin often became burned and blistered or peeled off when solvents were used to remove the remnants.

Discovering the attack

When I first discovered the Courtney brothers incident in the summer of 2020 – as Black Lives Matter protests took place worldwide following the May death of George Floyd – it felt monumental to me. Not only am I a historian at the university where this shameful event occurred, but I’ve also devoted the past five years to tracking down information about the Red Summer of 1919, the name given to the nationwide wave of violence against Black Americans that year.

University alumni records and yearbooks indicate the Courtney brothers never finished their studies. One article mentions possible legal action against the university, although I couldn’t find evidence of it.

Local media like The Bangor Daily News and the campus newspaper reported nothing on the event. A search of databases populated with millions of pages of historic newspapers yielded just six news accounts of the Courtney brothers incident. Most were published in the greater Boston area where the family was prominent, or in the Black press. While most of white America was unaware of the attack, many Black Americans likely read about it in The Chicago Defender, the most prominent and widely distributed Black paper in the nation at the time.

Anyone with firsthand memory of the incident is long gone. Samuel passed away in 1929 with no descendants. Roger, who worked in real estate investment, died a year later, leaving a pregnant wife and toddler behind. Obituaries for both men are brief and provide no details about their deaths. My efforts to speak with Courtney family members are ongoing.

No condemnationThe tarring and feathering is also missing from official University of Maine histories. A brief statement from the university’s then-president, Robert J. Aley, claimed the event was nothing more than childish hazing that was “likely to happen any time, at any college, the gravity depending much upon the susceptibilities of the victim and the notoriety given it.” Rather than condemn the mob’s violence, his statement highlighted the fact that one of the brothers had previously violated unspecified campus rules, as if that justified the treatment the men received.

A cross-country searchWhen I began my research on the Red Summer in 2015, almost no documents about the events were digitized, and resources were spread out across the country at dozens of different institutions.

I spent much of 2015 on a 7,500-mile cross-country journey, scouring material at over 20 archives, libraries and historical societies nationwide. On that trip, I collected digital copies of over 700 documents about this harrowing spike in anti-Black violence, including photographs of bodies on fire, reports of Black churches burned, court documents and coroners’ reports, telegrams documenting local government reactions and incendiary editorials that fueled the fire.

I built a database of riot dates and locations, number of people killed, sizes of mobs, number of arrests, supposed instigating factors and related archival material to piece together how these events were all connected. This data allowed me to create maps, timelines and other methods of examining that moment in history. While each event was different, many trends emerged, such as the role of labor and housing tension spurred by the first wave of the Great Migration or the prevalence of attacks against Black soldiers that year.

The end result, Visualizing the Red Summer, is now used in classrooms around the country. It has been featured or cited by Teaching Human Rights, the National Archives, History.com and the American Historical Association, among others.

Yet most Americans have still never heard about the Black sharecroppers killed in the Elaine Massacre in Arkansas that year for organizing their labor or the fatal stoning of Black Chicago teenager Eugene Williams for floating into “white waters” in Lake Michigan. They weren’t taught about the Black World War I soldiers attacked in Charleston, South Carolina, and Bisbee, Arizona, during the Red Summer.

There is still work to do, but the recent anniversaries of events like the Tulsa Massacre or the Red Summer, which coincided with modern-day Black Lives Matter protests and the killings of Americans like Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, have sparked a renewed interest in the past.

This new discovery brings my research back home to campus. It has afforded me an opportunity to engage students with the events of the Red Summer in new ways.

As the humanities specialist at the McGillicuddy Humanities Center, I worked with students in a public history class in the fall of 2020 to design a digital exhibit and walking tour of hidden histories at the University of Maine. This tour includes the attack on the Courtney brothers. Intentionally forgotten stories, or those buried out of shame or trauma, exist everywhere. By uncovering these local stories, it will become more clear how acts of violence against people of color are not limited to a particular time or place, but are rather part of collective American history.

While no first-person accounts or university records of the incident are known to remain, newspaper clippings and photographs from a former student’s scrapbook help fill in the details.

Although outnumbered, the Courtney brothers escaped. They knocked three freshmen attackers out cold in the process. Soon a mob of hundreds of students and community members formed to finish what the freshmen had started. The mob captured the brothers and led them about four miles back to campus with horse halters around their necks.

Before a growing crowd at the livestock-viewing pavilion, members of the mob held down Samuel and Roger as their heads were shaved and their bodies stripped naked in the near-freezing weather. They were forced to slop each other with hot molasses. The mob then covered them with feathers from their dorm room pillows. The victims and bystanders cried out for the mob to stop but to no avail. Local police, alerted hours earlier, arrived only after the incident ended. No arrests were made.

Incidents of tarring and feathering as a form of public torture can be found throughout American history, from colonial times onward. In nearby Ellsworth, Maine, a Know Nothing mob, seen by some as a forerunner to the KKK, tarred and feathered Jesuit priest Father John Bapst in 1851. Especially leading into World War I, this method of vigilantism continued to be used by the KKK and other groups against Black Americans, immigrants and labor organizers, especially in the South and West. As with the Courtney brothers incident, substitutions like molasses or milkweed were made based on what was readily available. Although rarely fatal, victims of tarring and feathering attacks were not only humiliated by being held down, shaved, stripped naked and covered in a boiled sticky substance and feathers, but their skin often became burned and blistered or peeled off when solvents were used to remove the remnants.

Discovering the attack

When I first discovered the Courtney brothers incident in the summer of 2020 – as Black Lives Matter protests took place worldwide following the May death of George Floyd – it felt monumental to me. Not only am I a historian at the university where this shameful event occurred, but I’ve also devoted the past five years to tracking down information about the Red Summer of 1919, the name given to the nationwide wave of violence against Black Americans that year.

University alumni records and yearbooks indicate the Courtney brothers never finished their studies. One article mentions possible legal action against the university, although I couldn’t find evidence of it.

Local media like The Bangor Daily News and the campus newspaper reported nothing on the event. A search of databases populated with millions of pages of historic newspapers yielded just six news accounts of the Courtney brothers incident. Most were published in the greater Boston area where the family was prominent, or in the Black press. While most of white America was unaware of the attack, many Black Americans likely read about it in The Chicago Defender, the most prominent and widely distributed Black paper in the nation at the time.

Anyone with firsthand memory of the incident is long gone. Samuel passed away in 1929 with no descendants. Roger, who worked in real estate investment, died a year later, leaving a pregnant wife and toddler behind. Obituaries for both men are brief and provide no details about their deaths. My efforts to speak with Courtney family members are ongoing.

No condemnationThe tarring and feathering is also missing from official University of Maine histories. A brief statement from the university’s then-president, Robert J. Aley, claimed the event was nothing more than childish hazing that was “likely to happen any time, at any college, the gravity depending much upon the susceptibilities of the victim and the notoriety given it.” Rather than condemn the mob’s violence, his statement highlighted the fact that one of the brothers had previously violated unspecified campus rules, as if that justified the treatment the men received.

A cross-country searchWhen I began my research on the Red Summer in 2015, almost no documents about the events were digitized, and resources were spread out across the country at dozens of different institutions.

I spent much of 2015 on a 7,500-mile cross-country journey, scouring material at over 20 archives, libraries and historical societies nationwide. On that trip, I collected digital copies of over 700 documents about this harrowing spike in anti-Black violence, including photographs of bodies on fire, reports of Black churches burned, court documents and coroners’ reports, telegrams documenting local government reactions and incendiary editorials that fueled the fire.

I built a database of riot dates and locations, number of people killed, sizes of mobs, number of arrests, supposed instigating factors and related archival material to piece together how these events were all connected. This data allowed me to create maps, timelines and other methods of examining that moment in history. While each event was different, many trends emerged, such as the role of labor and housing tension spurred by the first wave of the Great Migration or the prevalence of attacks against Black soldiers that year.

The end result, Visualizing the Red Summer, is now used in classrooms around the country. It has been featured or cited by Teaching Human Rights, the National Archives, History.com and the American Historical Association, among others.

Yet most Americans have still never heard about the Black sharecroppers killed in the Elaine Massacre in Arkansas that year for organizing their labor or the fatal stoning of Black Chicago teenager Eugene Williams for floating into “white waters” in Lake Michigan. They weren’t taught about the Black World War I soldiers attacked in Charleston, South Carolina, and Bisbee, Arizona, during the Red Summer.

There is still work to do, but the recent anniversaries of events like the Tulsa Massacre or the Red Summer, which coincided with modern-day Black Lives Matter protests and the killings of Americans like Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, have sparked a renewed interest in the past.

This new discovery brings my research back home to campus. It has afforded me an opportunity to engage students with the events of the Red Summer in new ways.

As the humanities specialist at the McGillicuddy Humanities Center, I worked with students in a public history class in the fall of 2020 to design a digital exhibit and walking tour of hidden histories at the University of Maine. This tour includes the attack on the Courtney brothers. Intentionally forgotten stories, or those buried out of shame or trauma, exist everywhere. By uncovering these local stories, it will become more clear how acts of violence against people of color are not limited to a particular time or place, but are rather part of collective American history.

Slave-built infrastructure still creates wealth in US, suggesting reparations should cover past harms and current value of slavery

THE CONVERSATION

February 5, 2021 1.27pm EST

American cities from Atlanta to New York City still use buildings, roads, ports and rail lines built by enslaved people.

The fact that centuries-old relics of slavery still support the economy of the United States suggests that reparations for slavery would need to go beyond government payments to the ancestors of enslaved people to account for profit-generating, slave-built infrastructure.

Debates about compensating Black Americans for slavery began soon after the Civil War, in the 1860s, with promises of “40 acres and a mule.” A national conversation about reparations has reignited in recent decades. The definition of reparations varies, but most advocates envision it as a two-part reckoning that acknowledges the role slavery played in building the country and directs resources to the communities impacted by slavery.

Through our geographic and urban planning scholarship, we document the contemporary infrastructure created by enslaved Black workers. Our study of what we call the “landscape of race” shows how the globally dominant economy of the United States traces directly back to slavery.

Looking again at railroads

While difficult to calculate, scholars estimate that much of the physical infrastructure built before 1860 in the American South was built with enslaved labor.

Railways were particularly critical infrastructure. According to “The American South,” an in-depth history of the region, railroads “offered solutions to the geographic barriers that segmented the South,” including swamps, mountains and rivers. For inland planters needing to get goods to port, trains were “the elemental precondition to better times.”

Our archival research on Montgomery, Alabama, shows that enslaved workers built and maintained the Montgomery Eufaula Railroad. This 81-mile-long railroad, begun in 1859, connected Montgomery to the Central Georgia Line, which served both Alabama’s fertile cotton-growing region – cotton picked by enslaved hands – and the textile mills of Georgia.

The Eufala Railroad also gave Alabama commercial access to the Port of Savannah. Savannah was a key cotton and rice trading port, and slavery was integral to the growth of the city.

Today, Savannah’s deep-water port remains one of the busiest container ports in the U.S. Among its top exports: cotton.

The Eufala Railroad closed in the 1970s. But the company that funded its construction – Lehman Durr & Co., a prominent Southern cotton brokerage – existed well into the 20th century.

Examining court affidavits and city records located in the Montgomery city archive, we learned the Montgomery Eufaula Railroad Company received US$1.8 million in loans from Lehman Durr & Co. The main backers of Lehman Durr & Co. went on to found Lehman Brothers bank, one of Wall Street’s largest investment banks until it collapsed in 2008, in the U.S. financial crisis.

Slave-built railroads also gave rise to Georgia’s largest city, Atlanta. In the 1830s, Atlanta was the terminus of a rail line that extended into the Midwest.

Some of these same rail lines still drive Georgia’s economy. According to a 2013 state report, railways that went through Georgia in 2012 carried over US$198 billion in agricultural products and raw materials needed for U.S. industry and manufacturing.

Rethinking reparations

Savannah, Atlanta and Montgomery all show how, far from being an artifact of history, as some critics of reparations suggest, slavery has a tangible presence in the American economy.

And not just in the South. Wall Street, in New York City, is associated with the trading of stocks. But in the 18th century, enslaved people were bought and sold there. Even after New York closed its slave markets, local businesses sold and shipped cotton grown in the slaveholding South.

Geographic research like ours could inform thinking on monetary reparations by helping to calculate the ongoing financial value of slavery.

Like scholarship drawing the connection between slavery and modern mass incarceration, however, our work also suggests that direct payments to indviduals cannot truly account for the modern legacy of slavery. It points toward a broader concept of reparations that reflects how slavery is built into the American landscape, still generating wealth.

Such reparations might include government investments in aspects of American life where Black people face disparities.

Last year the city council in Asheville, North Carolina, voted for “reparations in the form of community investment.” Priorities could include efforts to increase access to affordable housing and boost minority business ownership. Asheville will also explore strategies to close the racial gap in health care.

It is very difficult, perhaps impossible, to calculate the total contemporary economic impact of slavery. But we see recognizing that enslaved men, women and children built many of the cities, rail lines and ports that fuel the American economy as a necessary part of any such accounting.

The fact that centuries-old relics of slavery still support the economy of the United States suggests that reparations for slavery would need to go beyond government payments to the ancestors of enslaved people to account for profit-generating, slave-built infrastructure.

Debates about compensating Black Americans for slavery began soon after the Civil War, in the 1860s, with promises of “40 acres and a mule.” A national conversation about reparations has reignited in recent decades. The definition of reparations varies, but most advocates envision it as a two-part reckoning that acknowledges the role slavery played in building the country and directs resources to the communities impacted by slavery.

Through our geographic and urban planning scholarship, we document the contemporary infrastructure created by enslaved Black workers. Our study of what we call the “landscape of race” shows how the globally dominant economy of the United States traces directly back to slavery.

Looking again at railroads

While difficult to calculate, scholars estimate that much of the physical infrastructure built before 1860 in the American South was built with enslaved labor.

Railways were particularly critical infrastructure. According to “The American South,” an in-depth history of the region, railroads “offered solutions to the geographic barriers that segmented the South,” including swamps, mountains and rivers. For inland planters needing to get goods to port, trains were “the elemental precondition to better times.”

Our archival research on Montgomery, Alabama, shows that enslaved workers built and maintained the Montgomery Eufaula Railroad. This 81-mile-long railroad, begun in 1859, connected Montgomery to the Central Georgia Line, which served both Alabama’s fertile cotton-growing region – cotton picked by enslaved hands – and the textile mills of Georgia.

The Eufala Railroad also gave Alabama commercial access to the Port of Savannah. Savannah was a key cotton and rice trading port, and slavery was integral to the growth of the city.

Today, Savannah’s deep-water port remains one of the busiest container ports in the U.S. Among its top exports: cotton.

The Eufala Railroad closed in the 1970s. But the company that funded its construction – Lehman Durr & Co., a prominent Southern cotton brokerage – existed well into the 20th century.

Examining court affidavits and city records located in the Montgomery city archive, we learned the Montgomery Eufaula Railroad Company received US$1.8 million in loans from Lehman Durr & Co. The main backers of Lehman Durr & Co. went on to found Lehman Brothers bank, one of Wall Street’s largest investment banks until it collapsed in 2008, in the U.S. financial crisis.

Slave-built railroads also gave rise to Georgia’s largest city, Atlanta. In the 1830s, Atlanta was the terminus of a rail line that extended into the Midwest.

Some of these same rail lines still drive Georgia’s economy. According to a 2013 state report, railways that went through Georgia in 2012 carried over US$198 billion in agricultural products and raw materials needed for U.S. industry and manufacturing.

Rethinking reparations

Savannah, Atlanta and Montgomery all show how, far from being an artifact of history, as some critics of reparations suggest, slavery has a tangible presence in the American economy.

And not just in the South. Wall Street, in New York City, is associated with the trading of stocks. But in the 18th century, enslaved people were bought and sold there. Even after New York closed its slave markets, local businesses sold and shipped cotton grown in the slaveholding South.

Geographic research like ours could inform thinking on monetary reparations by helping to calculate the ongoing financial value of slavery.

Like scholarship drawing the connection between slavery and modern mass incarceration, however, our work also suggests that direct payments to indviduals cannot truly account for the modern legacy of slavery. It points toward a broader concept of reparations that reflects how slavery is built into the American landscape, still generating wealth.

Such reparations might include government investments in aspects of American life where Black people face disparities.

Last year the city council in Asheville, North Carolina, voted for “reparations in the form of community investment.” Priorities could include efforts to increase access to affordable housing and boost minority business ownership. Asheville will also explore strategies to close the racial gap in health care.

It is very difficult, perhaps impossible, to calculate the total contemporary economic impact of slavery. But we see recognizing that enslaved men, women and children built many of the cities, rail lines and ports that fuel the American economy as a necessary part of any such accounting.

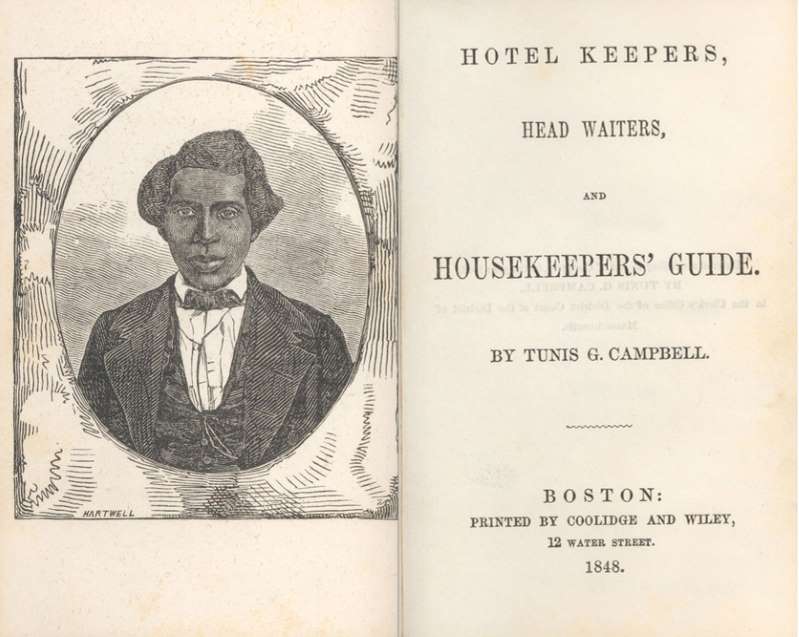

He fought for Black voting rights after the Civil War. He was almost killed for it.

Jess McHugh - washington post

10/25/2020

From the floor of the Georgia Senate, Tunis G. Campbell could see the glint of firearms. As he spoke, his fellow senators moved their hands to the butts of their guns, gesturing ever more threateningly the longer Campbell held the floor. Undeterred, he went on. The state senator continued to speak for seven consecutive days, arguing for a simple right: to stand exactly where he was.

Campbell was Black. It was 1868, and after only a few months in office, his opponents had voted that his skin color alone disqualified him from holding political office. After the eighth day, Campbell headed to Washington to petition the federal government to reinstate him and several other Black political officeholders who had been denied their elected seats. He would stay in Washington for several months to lobby for bills promoting Reconstruction in Georgia. “We went on — although threatened by many rebel sympathizers that if I went to Washington again I should not live in Georgia,” he would later write in his autobiography.

He did return to live in Georgia, this time as a sworn state senator. His fight for the equal rights of Black citizens has been mostly forgotten, but Campbell was one of the earliest people in Reconstruction-era Georgia fighting voter suppression. Using a militia of several hundred people to protect himself and other Black residents from White violence, Campbell served as a labor organizer, justice of the peace, voter registrar and state senator.

Some 150 years later, amid racial justice protests and voter suppression efforts, Campbell remains emblematic of the struggle to ensure Black Americans not only the right to vote, but also to exercise the full scope of citizenship: as activists, as small-business owners and as politicians.

Campbell spent his life championing the rights of Black people, meeting with fierce resistance at every step. During the course of his political career, he would be threatened, suffer an attempted assassination, see his house burned down and even be imprisoned and put on a chain gang. Despite grave danger to his health and family, Campbell dedicated his life to ensuring that freedmen would be free in every sense of the word: safe from physical violence and exploitative labor practices, while being able to practice their constitutional rights. It was his work ensuring the enfranchisement of all voters that left its mark on McIntosh County, Ga., well into the 20th century.

Mississippi’s first black senator was greeted with applause. But it wouldn’t last.

Born in 1812, Campbell was the son of a free blacksmith in New Jersey. He worked as a head waiter in a New York City hotel before gaining recognition as an abolitionist and a preacher. He came to the South by order of a general under President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed Campbell as the guardian of several islands off the coast of Georgia.

By the mid-1860s, he was selected to be a registrar. He and a biracial group of registrars traveled to several counties registering voters, as part of a larger effort across the state. The several dozen statewide Black registrars were often greeted with brutal violence: Campbell and another Black registrar were poisoned. The other registrar died, according to Campbell.

Yet the drive to register voters in Reconstruction Georgia — both Black and White — was exceptionally successful. By the fall of 1867, approximately 80 percent of men, or nearly 200,000 potential voters, had been registered, according to historian Edmund L. Drago. That included not only recently emancipated Black residents, but also some 95,000 low-income White men. The Black registrars also served a symbolic function: providing “the first contact many Southerners, White and Black, ever had with a black office-holder,” Drago wrote.

Lynching and other vicious crimes were a near-daily occurrence across the South during Reconstruction. In 1868 in Georgia alone, there would be 355 “outrages,” or violent attacks against free men, women and children, according to sociologist Richard Hogan.

Campbell forged ahead. He was on the ground at polling places, urging Black voters to stand up for their newly won rights, under any circumstances.

“You see all of the things we see now. We see voter suppression. We see Whites blocking voting venues and courthouses,” said Russell Duncan, a historian and author of a biography on Campbell.

By then, President Andrew Johnson had restored voting rights to former Confederates, but many abstained from the vote for the mere fact that there were Black candidates on the ballot. Black voters did not abstain, however, and many of them cast their first vote ever for Campbell. He cruised to victory.

When Campbell traveled to Washington after White opponents tried to deny him his seat, he spoke to Charles Sumner about the need for a 15th Amendment. Duncan suggests that Campbell’s specific wording for the amendment may have ended up in the Constitution itself. As a state senator, Campbell continued to lobby for fair voting practices, integrated juries, equal opportunities for education, and the abolition of imprisonment for debt.

He was the first Black man elected to Congress. But White lawmakers refused to seat him.

Campbell’s remarkable political career came to an abrupt halt in what one historian called a “judicial lynching.” As a justice of the peace, Campbell arbitrated both Black and White residents. He was known for levying fines on White landowners who mistreated their Black laborers. Some of the people had enslaved hundreds just a few years earlier — and appearing before a Black justice of the peace enraged them.

Campbell would be indicted on multiple charges in the mid-1870s, largely trumped up by those who saw the opportunity to finally oust him from the Georgia political arena. He petitioned many of his allies and sought a pardon from the governor and even from President Ulysses S. Grant. But those efforts failed. Campbell, then in his sixties, served his time — hard labor on a chain gang — and he left Georgia for good shortly afterward.

Just as early Reconstruction had ushered in a brief golden age of Black officeholders, they were violently ushered out. Historians estimate that some 2,000 Black people served in political roles during Reconstruction — as sheriffs, city councilors and members of Congress — a number not to be achieved again until the 1960s.

“There is almost always backlash, throughout U.S. history, to Black people gaining rights or making advancements,” said Ashleigh Lawrence-Sanders, an assistant professor of African American history who researches the Civil War and Reconstruction era. “And it’s not always just the backlash of the virulent racists; it’s also where they’re thrown to the wolves by people who are supposed to be their allies.”

Campbell may never have returned to Georgia, but his work left an indelible mark on McIntosh County. The region would remain — for the next four decades — a stronghold of Black political power.

Campbell was Black. It was 1868, and after only a few months in office, his opponents had voted that his skin color alone disqualified him from holding political office. After the eighth day, Campbell headed to Washington to petition the federal government to reinstate him and several other Black political officeholders who had been denied their elected seats. He would stay in Washington for several months to lobby for bills promoting Reconstruction in Georgia. “We went on — although threatened by many rebel sympathizers that if I went to Washington again I should not live in Georgia,” he would later write in his autobiography.

He did return to live in Georgia, this time as a sworn state senator. His fight for the equal rights of Black citizens has been mostly forgotten, but Campbell was one of the earliest people in Reconstruction-era Georgia fighting voter suppression. Using a militia of several hundred people to protect himself and other Black residents from White violence, Campbell served as a labor organizer, justice of the peace, voter registrar and state senator.

Some 150 years later, amid racial justice protests and voter suppression efforts, Campbell remains emblematic of the struggle to ensure Black Americans not only the right to vote, but also to exercise the full scope of citizenship: as activists, as small-business owners and as politicians.

Campbell spent his life championing the rights of Black people, meeting with fierce resistance at every step. During the course of his political career, he would be threatened, suffer an attempted assassination, see his house burned down and even be imprisoned and put on a chain gang. Despite grave danger to his health and family, Campbell dedicated his life to ensuring that freedmen would be free in every sense of the word: safe from physical violence and exploitative labor practices, while being able to practice their constitutional rights. It was his work ensuring the enfranchisement of all voters that left its mark on McIntosh County, Ga., well into the 20th century.

Mississippi’s first black senator was greeted with applause. But it wouldn’t last.

Born in 1812, Campbell was the son of a free blacksmith in New Jersey. He worked as a head waiter in a New York City hotel before gaining recognition as an abolitionist and a preacher. He came to the South by order of a general under President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed Campbell as the guardian of several islands off the coast of Georgia.

By the mid-1860s, he was selected to be a registrar. He and a biracial group of registrars traveled to several counties registering voters, as part of a larger effort across the state. The several dozen statewide Black registrars were often greeted with brutal violence: Campbell and another Black registrar were poisoned. The other registrar died, according to Campbell.

Yet the drive to register voters in Reconstruction Georgia — both Black and White — was exceptionally successful. By the fall of 1867, approximately 80 percent of men, or nearly 200,000 potential voters, had been registered, according to historian Edmund L. Drago. That included not only recently emancipated Black residents, but also some 95,000 low-income White men. The Black registrars also served a symbolic function: providing “the first contact many Southerners, White and Black, ever had with a black office-holder,” Drago wrote.

Lynching and other vicious crimes were a near-daily occurrence across the South during Reconstruction. In 1868 in Georgia alone, there would be 355 “outrages,” or violent attacks against free men, women and children, according to sociologist Richard Hogan.

Campbell forged ahead. He was on the ground at polling places, urging Black voters to stand up for their newly won rights, under any circumstances.

“You see all of the things we see now. We see voter suppression. We see Whites blocking voting venues and courthouses,” said Russell Duncan, a historian and author of a biography on Campbell.

By then, President Andrew Johnson had restored voting rights to former Confederates, but many abstained from the vote for the mere fact that there were Black candidates on the ballot. Black voters did not abstain, however, and many of them cast their first vote ever for Campbell. He cruised to victory.

When Campbell traveled to Washington after White opponents tried to deny him his seat, he spoke to Charles Sumner about the need for a 15th Amendment. Duncan suggests that Campbell’s specific wording for the amendment may have ended up in the Constitution itself. As a state senator, Campbell continued to lobby for fair voting practices, integrated juries, equal opportunities for education, and the abolition of imprisonment for debt.

He was the first Black man elected to Congress. But White lawmakers refused to seat him.

Campbell’s remarkable political career came to an abrupt halt in what one historian called a “judicial lynching.” As a justice of the peace, Campbell arbitrated both Black and White residents. He was known for levying fines on White landowners who mistreated their Black laborers. Some of the people had enslaved hundreds just a few years earlier — and appearing before a Black justice of the peace enraged them.

Campbell would be indicted on multiple charges in the mid-1870s, largely trumped up by those who saw the opportunity to finally oust him from the Georgia political arena. He petitioned many of his allies and sought a pardon from the governor and even from President Ulysses S. Grant. But those efforts failed. Campbell, then in his sixties, served his time — hard labor on a chain gang — and he left Georgia for good shortly afterward.

Just as early Reconstruction had ushered in a brief golden age of Black officeholders, they were violently ushered out. Historians estimate that some 2,000 Black people served in political roles during Reconstruction — as sheriffs, city councilors and members of Congress — a number not to be achieved again until the 1960s.

“There is almost always backlash, throughout U.S. history, to Black people gaining rights or making advancements,” said Ashleigh Lawrence-Sanders, an assistant professor of African American history who researches the Civil War and Reconstruction era. “And it’s not always just the backlash of the virulent racists; it’s also where they’re thrown to the wolves by people who are supposed to be their allies.”

Campbell may never have returned to Georgia, but his work left an indelible mark on McIntosh County. The region would remain — for the next four decades — a stronghold of Black political power.

Feminism, flour bombs and the first black Miss World

Millions watched as protesters took over the 1970 Miss World contest. Now, as a film recounts the story, Jennifer Hosten tells of winning the crown and her own battle with racism

Rob Walker

the guardian

Sun 9 Feb 2020 02.55 EST

It was the era of apartheid in South Africa, the civil rights movement in America and women’s liberation in Britain. And they all came together at one of the most-watched live television events of the time, when feminist protesters stormed the stage at Miss World 1970, and a black woman walked away from the beauty contest with the crown for the first time.

Fifty years on, that night is being retold in a film, Misbehaviour, inspired by the memoir of Jennifer Hosten, who won the contest and made history. In the decades that have followed, the one-time beauty queen has come to the conclusion that she and the women disrupting the competition had more in common than they might have thought.

“I didn’t realise it fully at the time but we were all using that contest as a way to get a message across,” she told the Observer last week. “For me it was about race and inclusion – for them, it was about female exploitation.”

Hosten, who came from the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada to scoop the crown at the age of 23, was peeking through the stage curtain at the Royal Albert Hall, a few feet from compere Bob Hope as he delivered his now infamous opening remarks.

“I don’t want you to think I’m a dirty old man because I never give women a second thought,” he said. “My first thought covers everything.”

“He was struggling,” remembered Hosten, now 72. She recalled hearing a firecracker go off and seeing people running scared. But the huge bang was from a group of well-dressed women who had started pelting the US comedian with flour bombs, then rose up in outrage. “We’re not beautiful, we’re not ugly. We’re ANGRY!” they screamed.

“It was an incredible commotion,” Hosten said.

The supposed firecracker was actually a football rattle, sounded by a women’s liberation activist and designed as a cue for the other feminists strategically planted among the audience to leap into action. The plan had been to kick things off when the contestants were on stage being paraded around in their swimwear, but Hosten says the women were so outraged by Hope’s jokes that the rattle went off early. “It was a big deal then, it’s still a big deal now!” she added.

Watched on TV by over 22 million people in Britain, and 100 million worldwide, the incident was seen as a galvanising moment for the women’s liberation movement and is to be retold in the film starring Keira Knightley, Gugu Mbatha-Raw and Jessie Buckley later this year. Hosten’s memoir, Miss World 1970, will be published next month.

But for Hosten it was also a big win for racial equality. Not only was she crowned Miss World but her friend, Pearl Jansen from South Africa, was the runner-up. Organisers had been shamed into sending her, a black contestant, at the last minute but Jansen had to be known as Miss Africa South because there was already a white Miss South Africa.

Hosten recalls Jansen telling her there was a reason for black women being represented at the contest that was “much more important than just representing our country”.

Her success, however, outraged sections of the tabloid media. The Sun newspaper presented Hosten’s victory as a conspiracy by black members of the judging panel. “How else could a black girl with 25:1 odds have walked away with the title? That’s what they were saying,” she said.

And it wasn’t only the press. Eric Morley – the then head of the Miss World beauty business – had handpicked 15 of the 58 contestants for a dress rehearsal the night before the event, parading them before the cameras. “They were his favourites,” Hosten said. “But only one of them – Miss Guyana – was a woman of colour. The rest of us were told to go and sit down with the audience.”

Hosten was shocked. Growing up in Grenada she had not thought much about skin colour. That changed when she arrived in Britain for the show.

“It was such an eye-opener, seeing the way the media only saw beauty by European standards. It was supposed to be Miss World – people of different races and different cultures. Most of us were written off before we even started.”

It made her participation much more meaningful, she said. “It made me want to win.”

When she did just that she was celebrated right across the Caribbean. In 1970 Grenada still didn’t have independence from Britain, so it was an opportunity to put her small country on the map. “I showed off my country and showed that women can do anything,” she said.

In the 50 years since then, the world has moved on. Last year, for the first time in history, Miss World, Miss Universe, Miss USA, Miss Teen USA and Miss America were all won by women of colour. “The question is, though, why are we talking about that?” said Hosten. “The fact that we’re talking about it as a big deal means to say that it is still a big deal.”

Fifty years on, that night is being retold in a film, Misbehaviour, inspired by the memoir of Jennifer Hosten, who won the contest and made history. In the decades that have followed, the one-time beauty queen has come to the conclusion that she and the women disrupting the competition had more in common than they might have thought.

“I didn’t realise it fully at the time but we were all using that contest as a way to get a message across,” she told the Observer last week. “For me it was about race and inclusion – for them, it was about female exploitation.”

Hosten, who came from the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada to scoop the crown at the age of 23, was peeking through the stage curtain at the Royal Albert Hall, a few feet from compere Bob Hope as he delivered his now infamous opening remarks.

“I don’t want you to think I’m a dirty old man because I never give women a second thought,” he said. “My first thought covers everything.”

“He was struggling,” remembered Hosten, now 72. She recalled hearing a firecracker go off and seeing people running scared. But the huge bang was from a group of well-dressed women who had started pelting the US comedian with flour bombs, then rose up in outrage. “We’re not beautiful, we’re not ugly. We’re ANGRY!” they screamed.

“It was an incredible commotion,” Hosten said.

The supposed firecracker was actually a football rattle, sounded by a women’s liberation activist and designed as a cue for the other feminists strategically planted among the audience to leap into action. The plan had been to kick things off when the contestants were on stage being paraded around in their swimwear, but Hosten says the women were so outraged by Hope’s jokes that the rattle went off early. “It was a big deal then, it’s still a big deal now!” she added.

Watched on TV by over 22 million people in Britain, and 100 million worldwide, the incident was seen as a galvanising moment for the women’s liberation movement and is to be retold in the film starring Keira Knightley, Gugu Mbatha-Raw and Jessie Buckley later this year. Hosten’s memoir, Miss World 1970, will be published next month.

But for Hosten it was also a big win for racial equality. Not only was she crowned Miss World but her friend, Pearl Jansen from South Africa, was the runner-up. Organisers had been shamed into sending her, a black contestant, at the last minute but Jansen had to be known as Miss Africa South because there was already a white Miss South Africa.

Hosten recalls Jansen telling her there was a reason for black women being represented at the contest that was “much more important than just representing our country”.

Her success, however, outraged sections of the tabloid media. The Sun newspaper presented Hosten’s victory as a conspiracy by black members of the judging panel. “How else could a black girl with 25:1 odds have walked away with the title? That’s what they were saying,” she said.

And it wasn’t only the press. Eric Morley – the then head of the Miss World beauty business – had handpicked 15 of the 58 contestants for a dress rehearsal the night before the event, parading them before the cameras. “They were his favourites,” Hosten said. “But only one of them – Miss Guyana – was a woman of colour. The rest of us were told to go and sit down with the audience.”

Hosten was shocked. Growing up in Grenada she had not thought much about skin colour. That changed when she arrived in Britain for the show.

“It was such an eye-opener, seeing the way the media only saw beauty by European standards. It was supposed to be Miss World – people of different races and different cultures. Most of us were written off before we even started.”

It made her participation much more meaningful, she said. “It made me want to win.”

When she did just that she was celebrated right across the Caribbean. In 1970 Grenada still didn’t have independence from Britain, so it was an opportunity to put her small country on the map. “I showed off my country and showed that women can do anything,” she said.

In the 50 years since then, the world has moved on. Last year, for the first time in history, Miss World, Miss Universe, Miss USA, Miss Teen USA and Miss America were all won by women of colour. “The question is, though, why are we talking about that?” said Hosten. “The fact that we’re talking about it as a big deal means to say that it is still a big deal.”

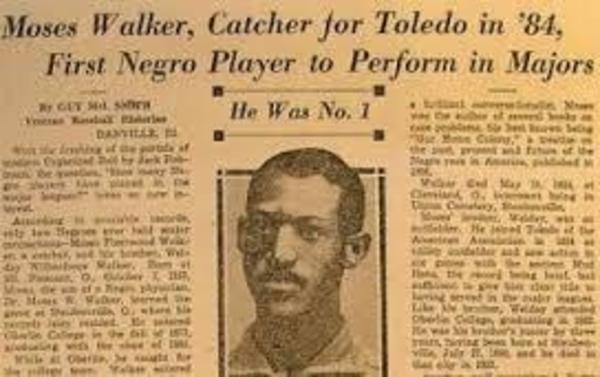

Curator Uncovers Black Baseball Team That Dominated Before Integration of Sport

By Tanasia Kenney - atlanta black star

February 2, 2020

Louisville’s Slugger Museum & Factory is a one-stop shop for all things baseball, so curators were thrilled when they became the new owners of what they thought were snapshots of one Negro Leagues baseball team, the Louisville White Sox.

Little did they know they had stumbled across a rare find.