TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

WELCOME TO REALITY TRIVIA

earth

it ain't flat, just endangered by the foolish and the greedy!

AUGUST 2022

"The modern conservative [and, I would say, the human supremacist] is engaged in one of man’s oldest exercises in moral philosophy; that is, the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness."

—John Kenneth Galbraith

The Myth of Human Supremacy by Derrick Jensen (Seven Stories Press, 2016):

headlines ~ ENVIRONMENT and climate change

*EARTH IS SPINNING FASTER THAN IT SHOULD BE AND NO ONE IS SURE WHY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Wait, We Can Mine Valuable Metals Using Shrubbery?

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A SLOWING CURRENT SYSTEM IN THE ATLANTIC OCEAN SPELLS TROUBLE FOR EARTH

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Forest the size of France regrown worldwide over 20 years, study finds

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ATLANTIC OCEAN CIRCULATION AT WEAKEST IN A MILLENNIUM, SAY SCIENTISTS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Fifth of countries at risk of ecosystem collapse, analysis finds

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Satellite images show rapid growth of glacial lakes worldwide

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A methane leak in Antarctica provides new insight into how methane-eating microbes evolve (ARTICLE BELOW)

*North Atlantic right whales now officially 'one step from extinction'

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*World has six months to avert climate crisis, says energy expert

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Russia says ‘years’ needed to clean up Arctic spill

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Lockdowns trigger dramatic fall in global carbon emissions

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*One billion people will live in insufferable heat within 50 years – study

(ARTICLE BELOW)

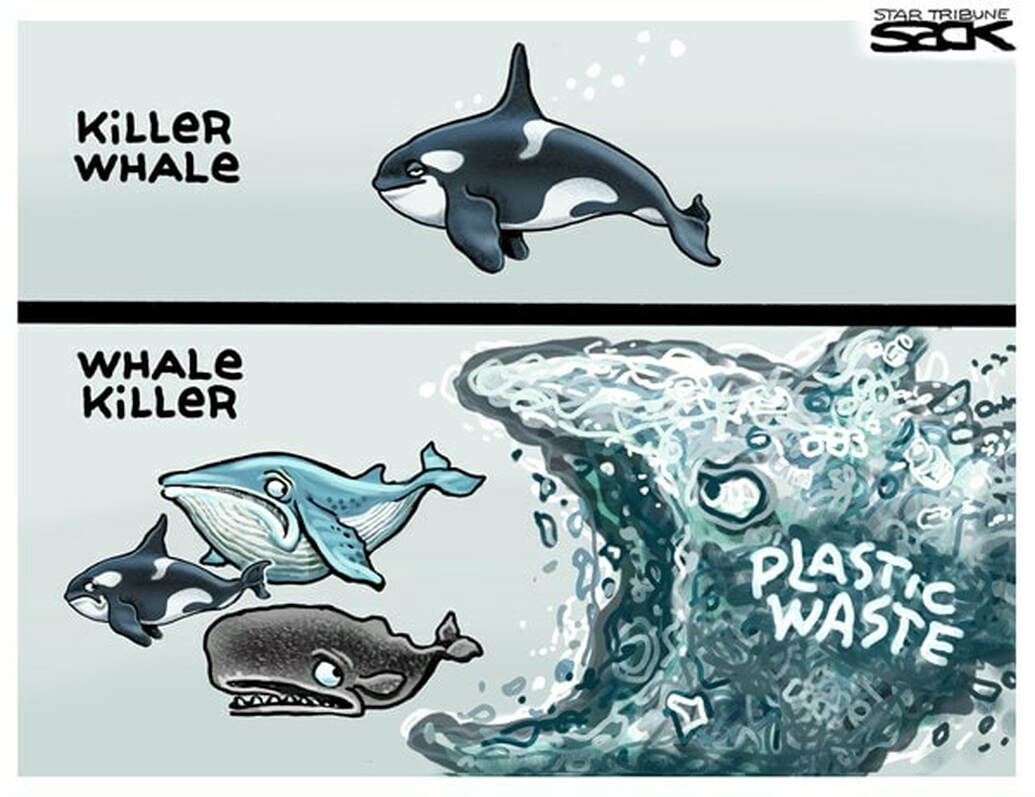

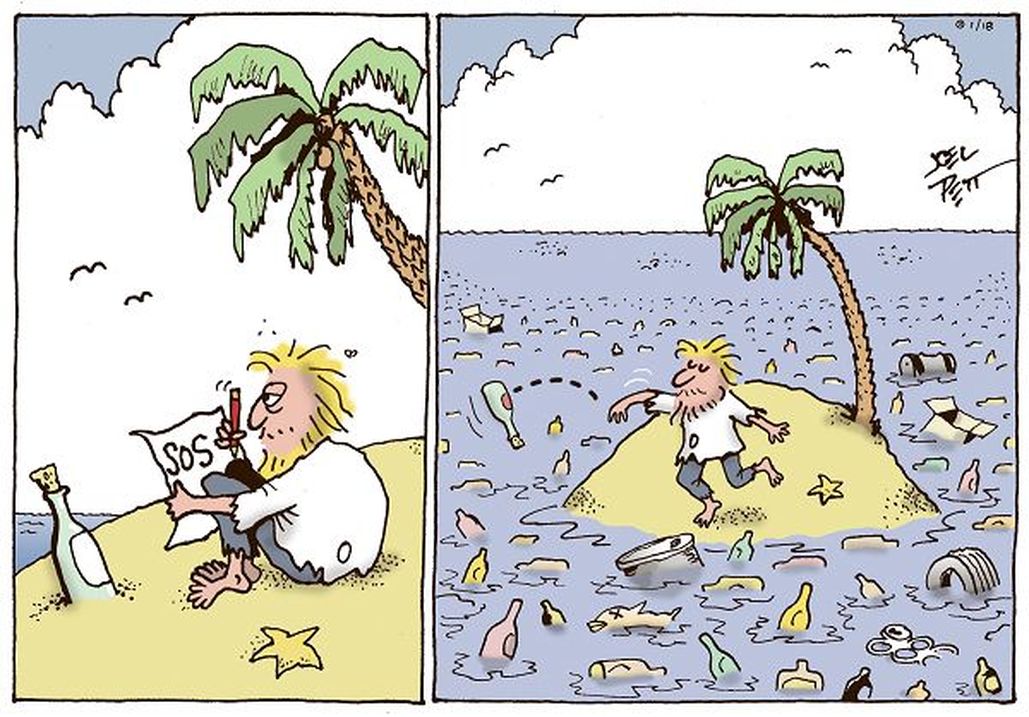

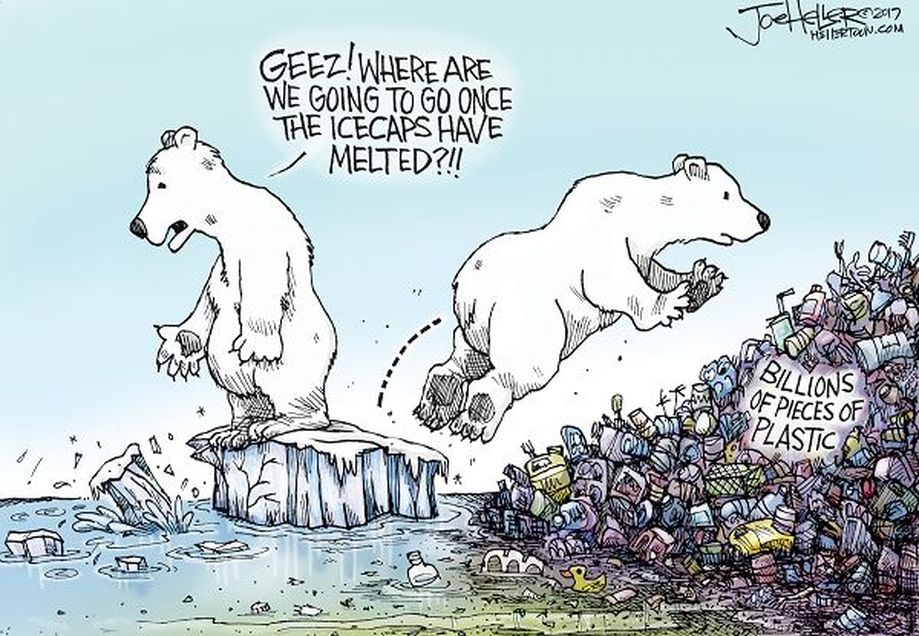

*Ocean plastic was choking Chile’s shores. Now it’s in Patagonia’s hats

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Global warming to cause ‘catastrophic’ species loss: study

(ARTICLE BELOW)

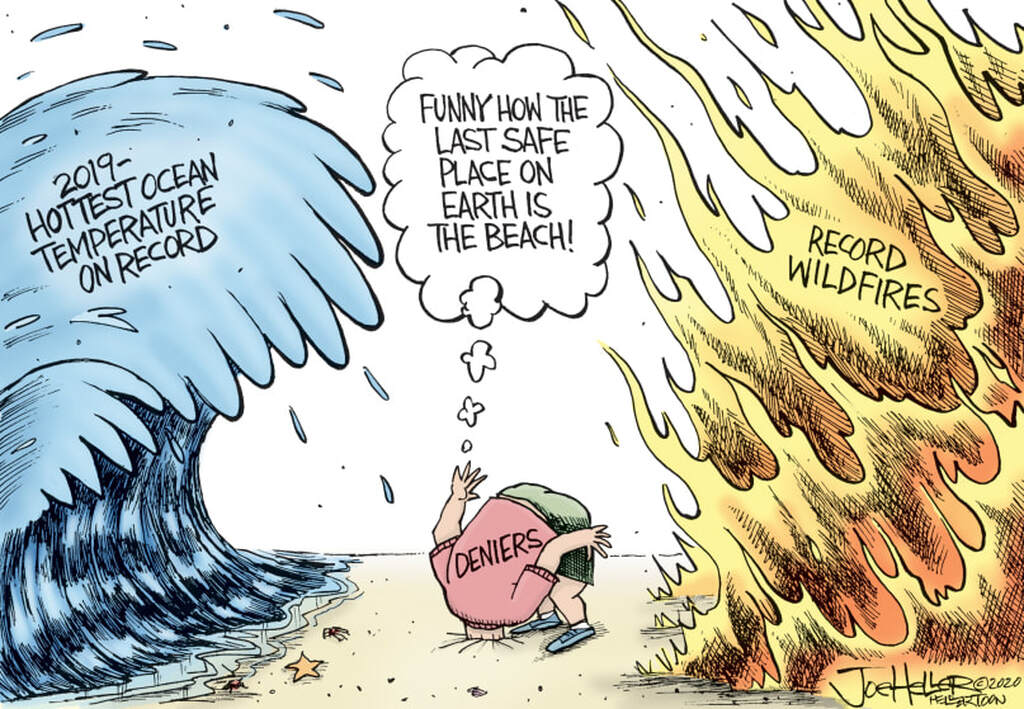

*Polar ice caps melting six times faster than in 1990s

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*NEW SPECIES FOUND IN EARTH'S DEEPEST TRENCH HAS PLASTIC IN ITS BODY—SO SCIENTISTS HAVE NAMED IT EURYTHENES (ARTICLE BELOW)

*STUDY: AIR POLLUTION SHORTENS LIVES BY AVERAGE OF 2.9 YEARS, CAUSES 8.8 MILLION EARLY DEATHS A YEAR(ARTICLE BELOW)

*World's beaches disappearing due to climate crisis – study

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The world is failing to ensure children have a 'liveable planet', report finds

(ARTICLE BELOW)

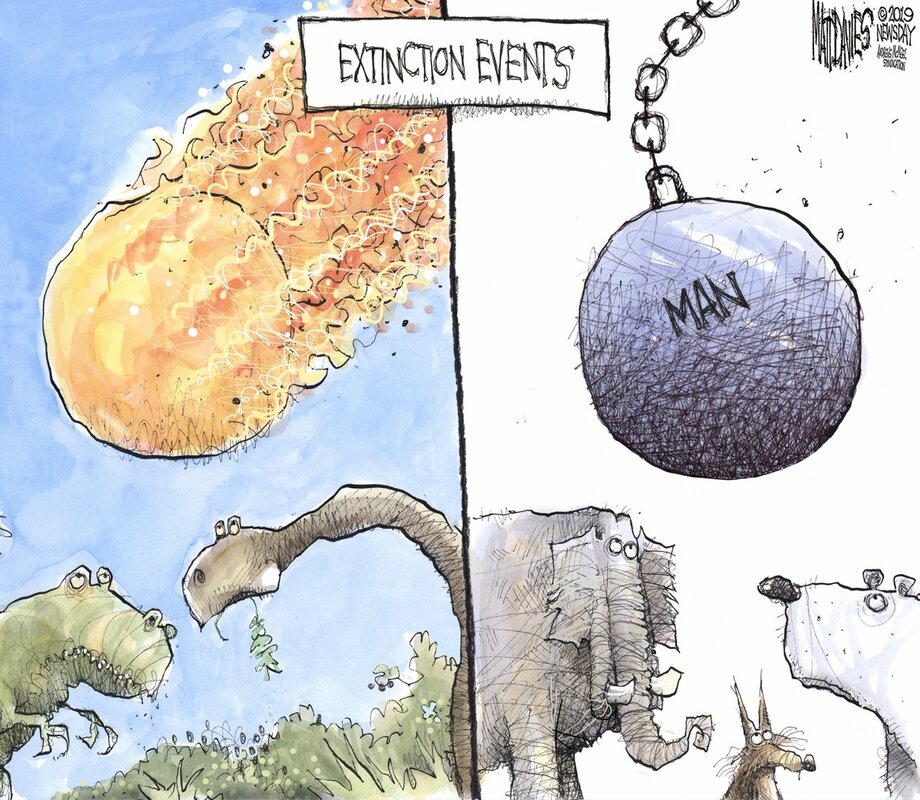

*HALF-A-MILLION INSECT SPECIES FACE EXTINCTION: SCIENTISTS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Scientists fear the ‘doomsday glacier’ is in even more trouble than we feared

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Relative of extinct tortoise located in Galapagos

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Tropical Forests Are Losing the Ability to Absorb CO2, Study Says

(excerpt BELOW)

*Race to exploit the world’s seabed set to wreak havoc on marine life

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Study finds shock rise in levels of potent greenhouse gas

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Ocean temperatures hit record high as rate of heating accelerates

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Statistic of the decade: The massive deforestation of the Amazon

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Climate-heating greenhouse gases hit new high, UN reports

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Last Surviving Sumatran Rhino in Malaysia Dies

(ARTICLE BELOW)

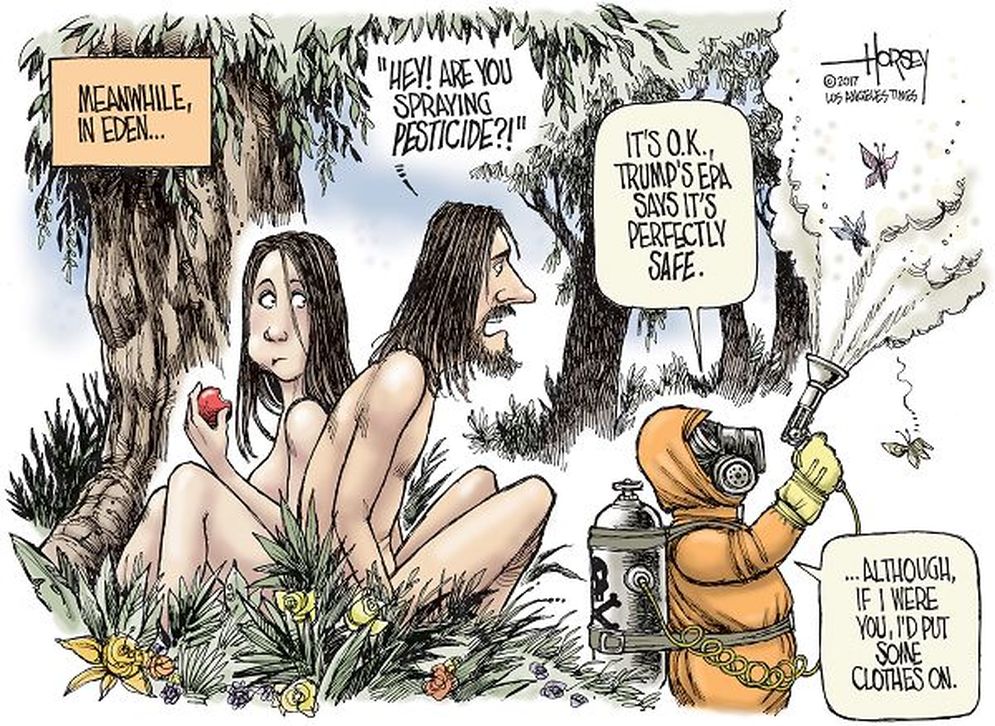

*Regenerative, Organic Agriculture is Essential to Fighting Climate Change

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Scientists Say a Quarter of Pigs Around the World Could Die of Swine Fever

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*SEA 'BOILING' WITH METHANE DISCOVERED IN SIBERIA: 'NO ONE HAS EVER RECORDED ANYTHING LIKE THIS BEFORE'(ARTICLE BELOW)

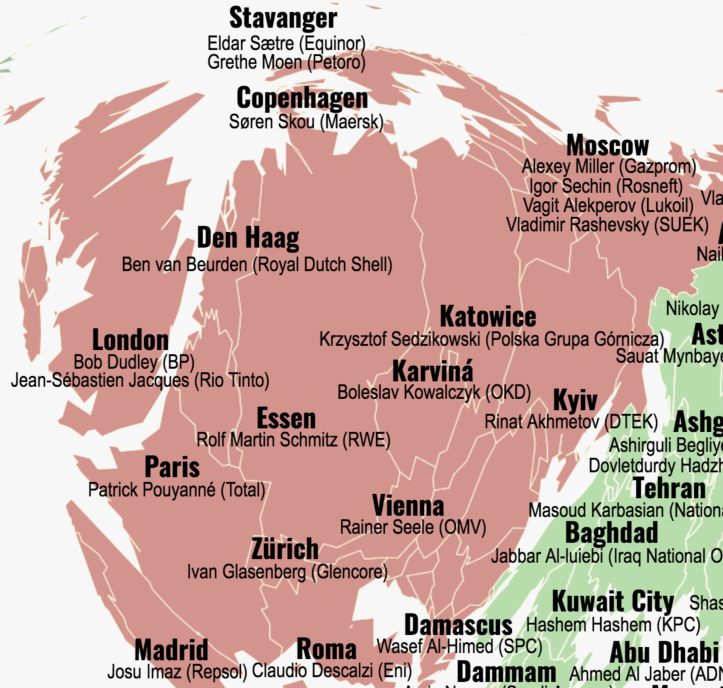

*Names and Locations of the Top 100 People Killing the Planet

(ARTICLE BELOW)

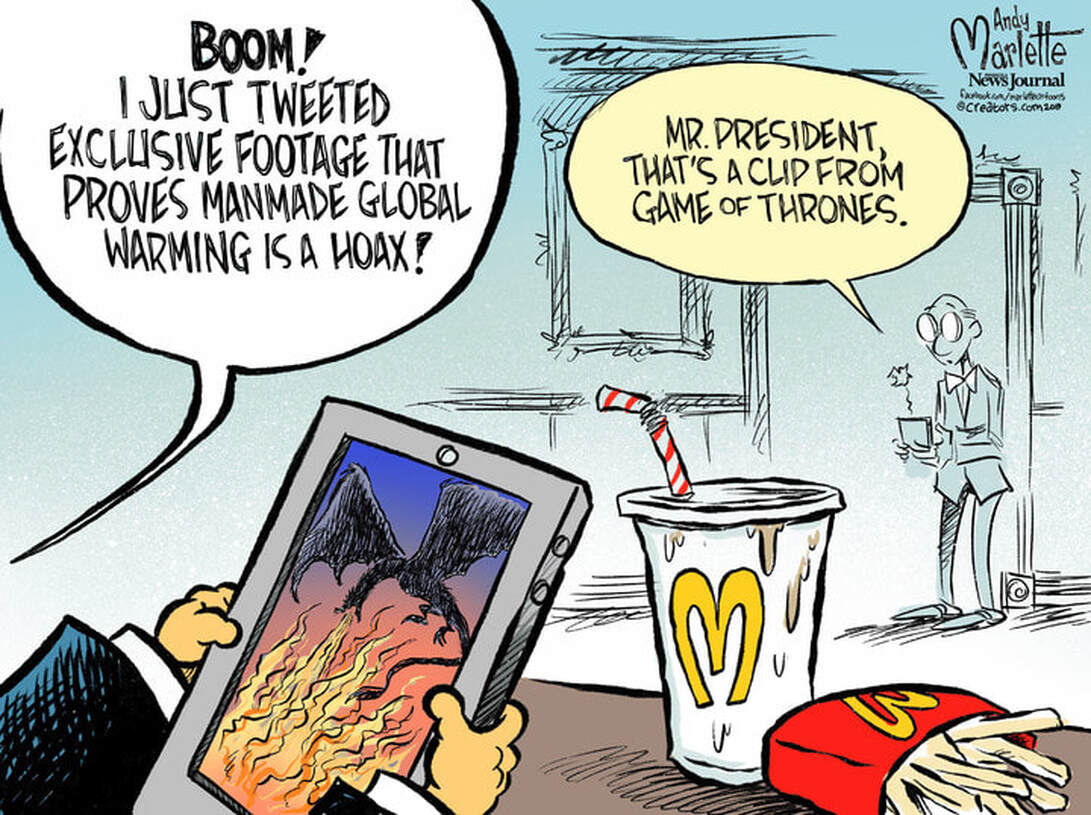

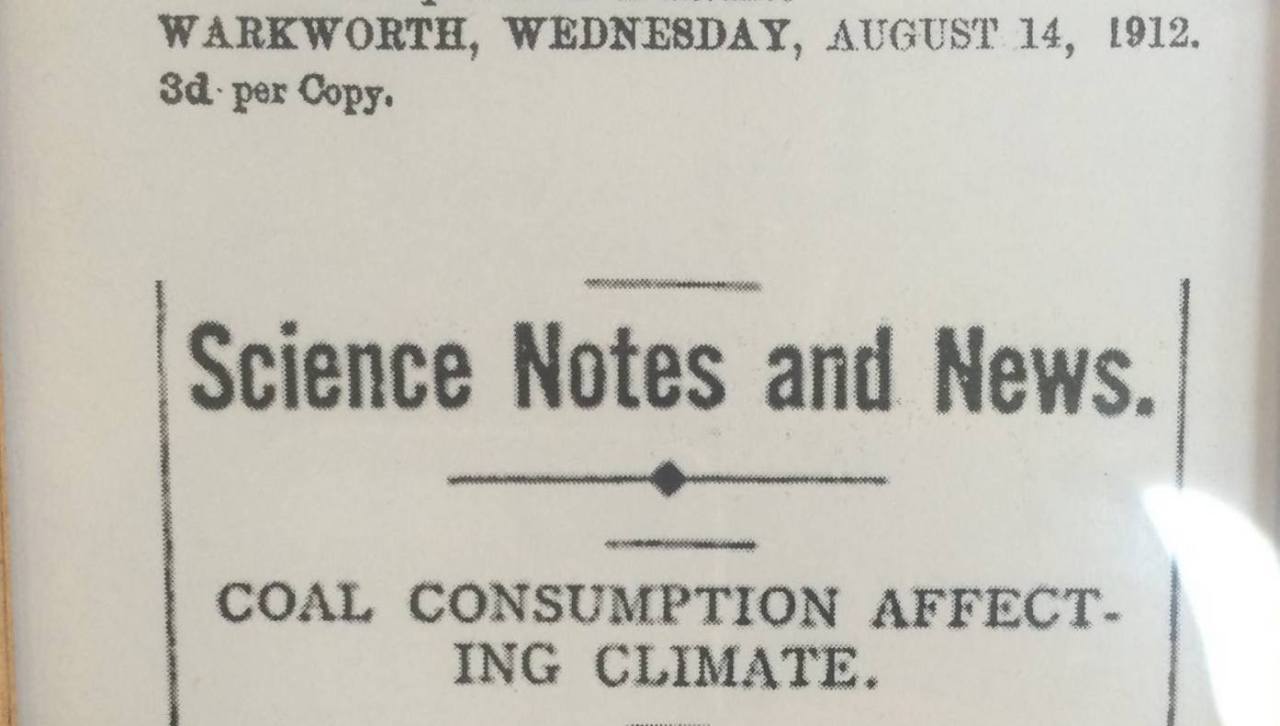

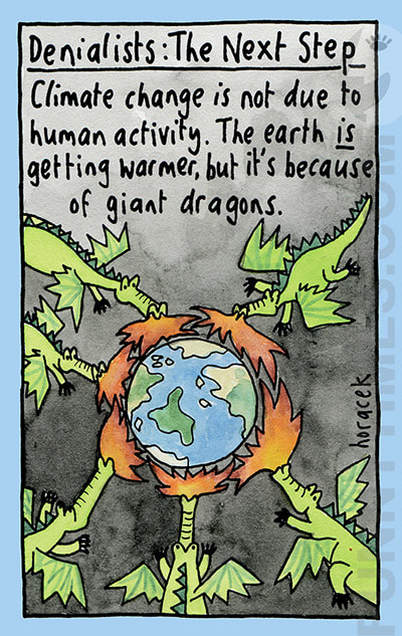

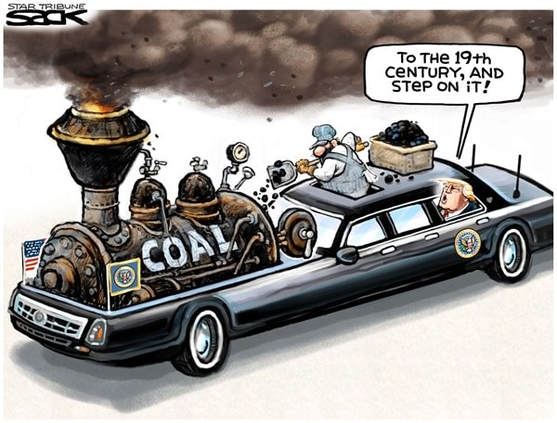

*SCIENTISTS HAVE KNOWN BURNING COAL WARMS THE CLIMATE FOR A LONG TIME. THIS 1912 HEADLINE PROVES IT.(ARTICLE BELOW)

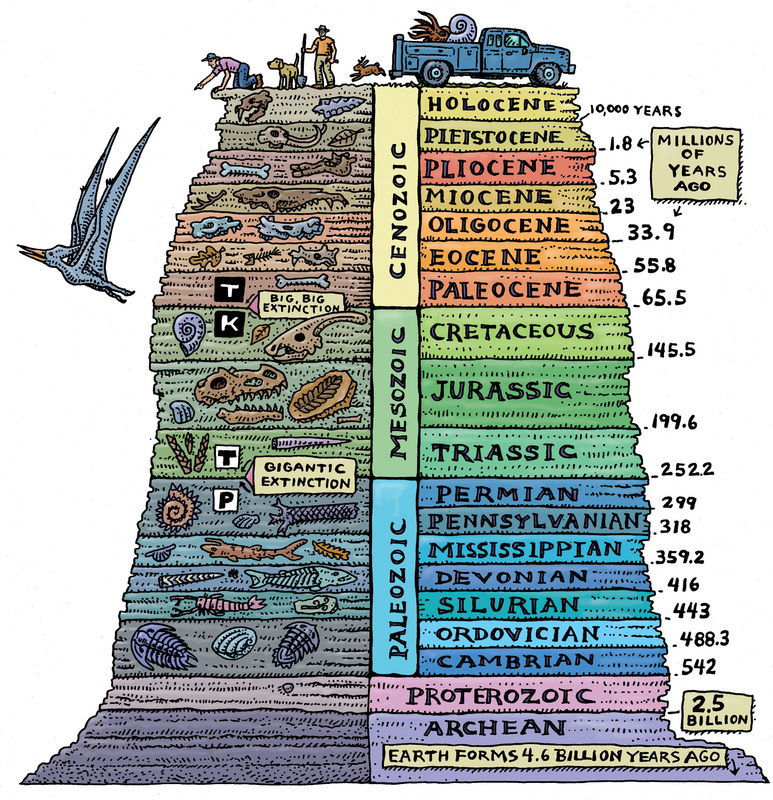

*The Anthropocene epoch: scientists declare dawn of human-influenced age(excerpt below)

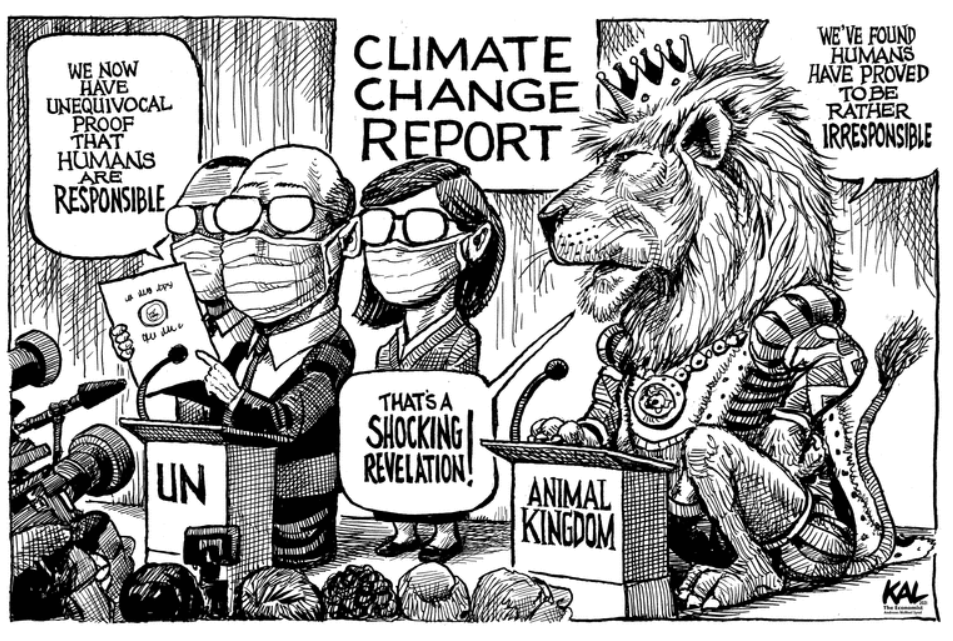

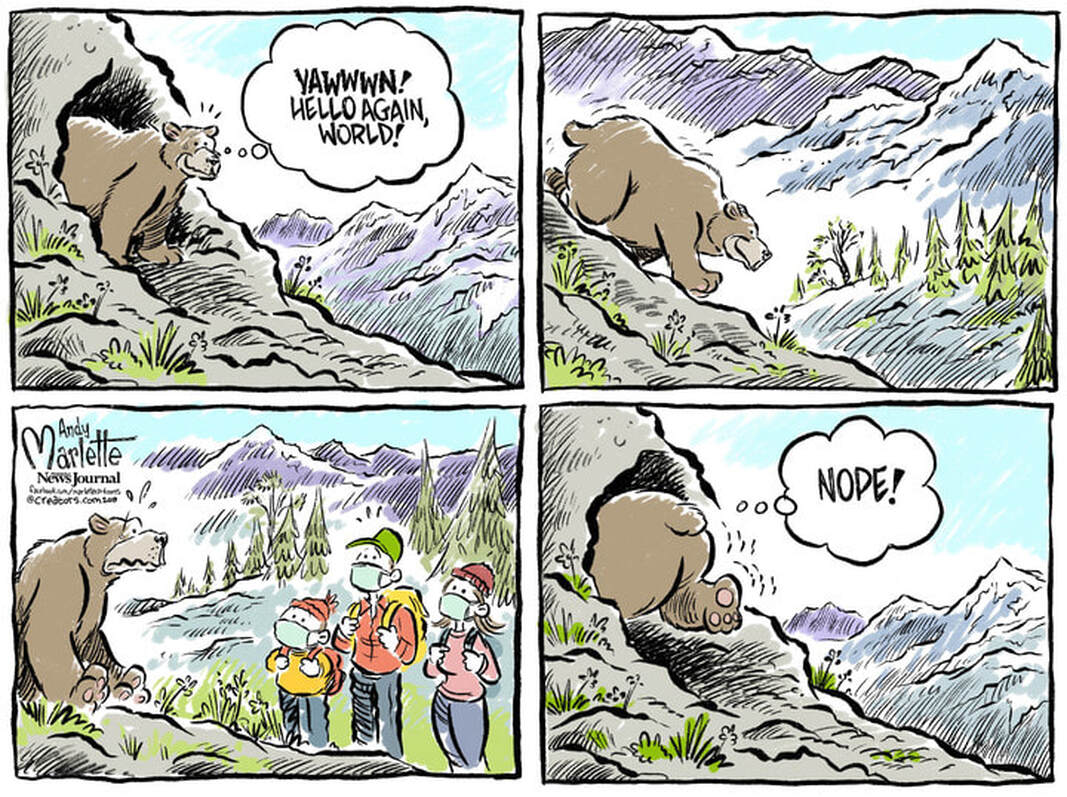

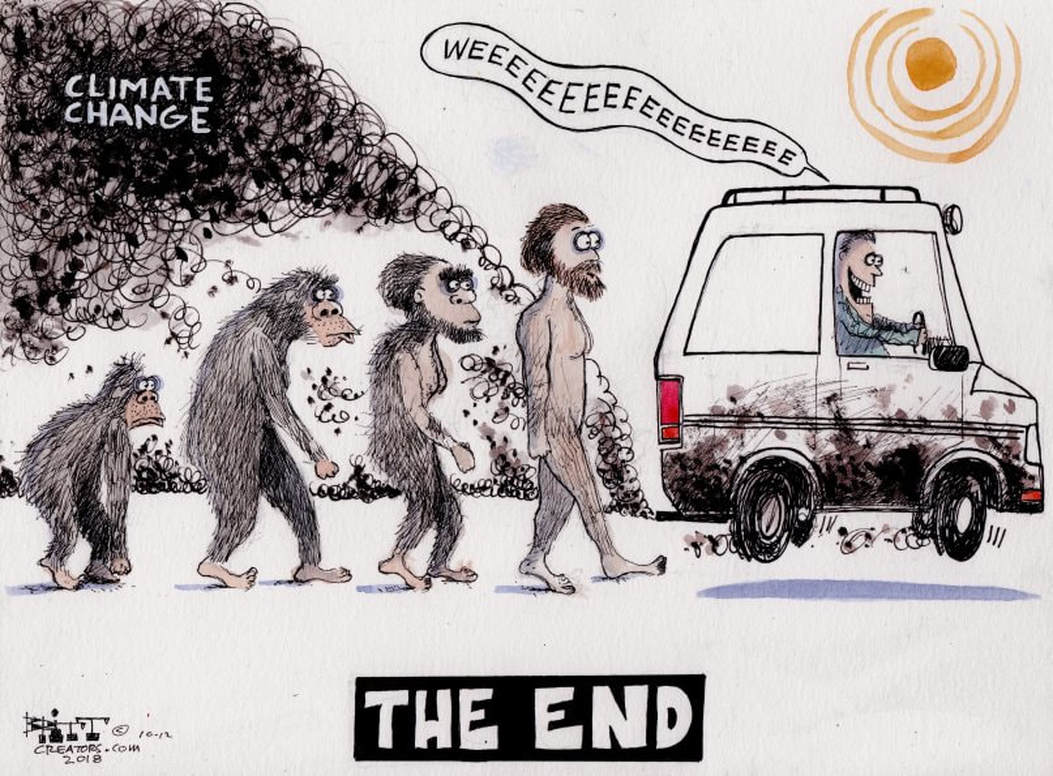

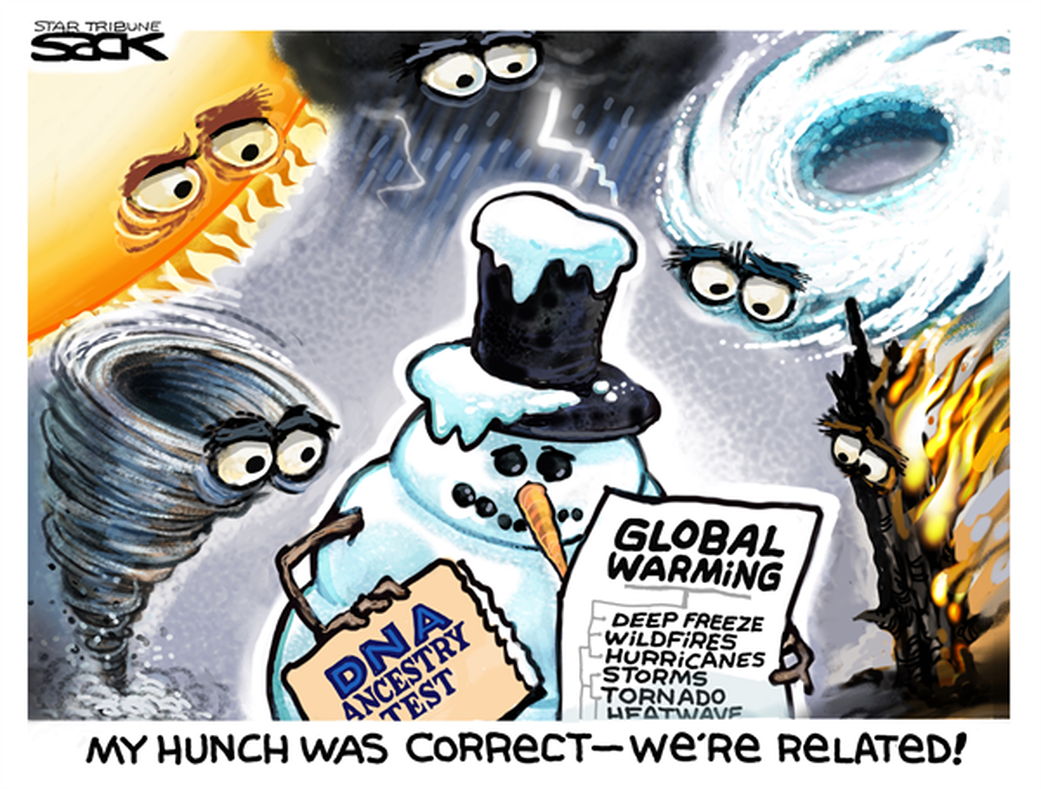

*earth funnies(at the end)

Earth is spinning faster than it should be and no one is sure why

The planet recorded two of its shortest days in recent history. What is going on?

By NICOLE KARLIS - salon

PUBLISHED AUGUST 5, 2022 4:00PM (EDT)

If the days feel like they get shorter as you get older, you may not be imagining it.

On June 29, 2022, the Earth made one full rotation that took 1.59 milliseconds less than the average day length of 86,400 seconds, or 24 hours. While a 1.59 millisecond shortening might not seem like much, it is part of a larger and peculiar trend.

Indeed, on July 26, 2022, another new record was nearly set when the Earth finished its day 1.50 milliseconds shorter than usual, as reported by The Guardian and the time-tracking website Time and Date. Time and Date notes that the year 2020 had the highest number of short days since scientists started using atomic clocks to take daily measurements in the 1960s. Scientists first started to notice the trend in 2016.

While the length of an average day may vary slightly in the short-term, in the long-term the length of the day has been increasing since the Earth-moon system was formed. That's because over time, the force of gravity has moved energy from the Earth — via the tides — to the Moon, pushing it slightly further away from us. Meanwhile, because the two bodies are in tidal lock — meaning the Moon's rate of rotation and revolution are equivalent such that we only ever see one of its sides — physics dictates that the Earth's day must lengthen if the two bodies are to remain in tidal lock as the moon moves further away. Billions of years ago, the Moon was much closer and the length of Earth's day much shorter.

While scientists know that the Earth's days are shortening on a short-term scale, a definitive reason as to why remains unclear— along with the effect it might have on how we as humans track time.

"The rotation rate of Earth is a complicated business. It has to do with exchange of angular momentum between Earth and the atmosphere and the effects of the ocean and the effect of the moon," Judah Levine, a physicist in the time and frequency division of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, told Discover Magazine. "You're not able to predict what's going to happen very far in the future."

But Fred Watson, Australia's astronomer-at-large, told ABC News in Australia that if nothing is done to stop it, "you are going to gradually get the seasons out of step with the calendar."

"When you start looking at the real nitty gritty, you realize that Earth is not just a solid ball that is spinning," Watson said. "It's got liquid on the inside, it's got liquid on the outside, and it's got an atmosphere and all of these things slosh around a bit."

Matt King from University of Tasmania described the trend to ABC News Australia as "certainly odd."

"Clearly something has changed, and changed in a way we haven't seen since the beginning of precise radio astronomy in the 1970s," King said.

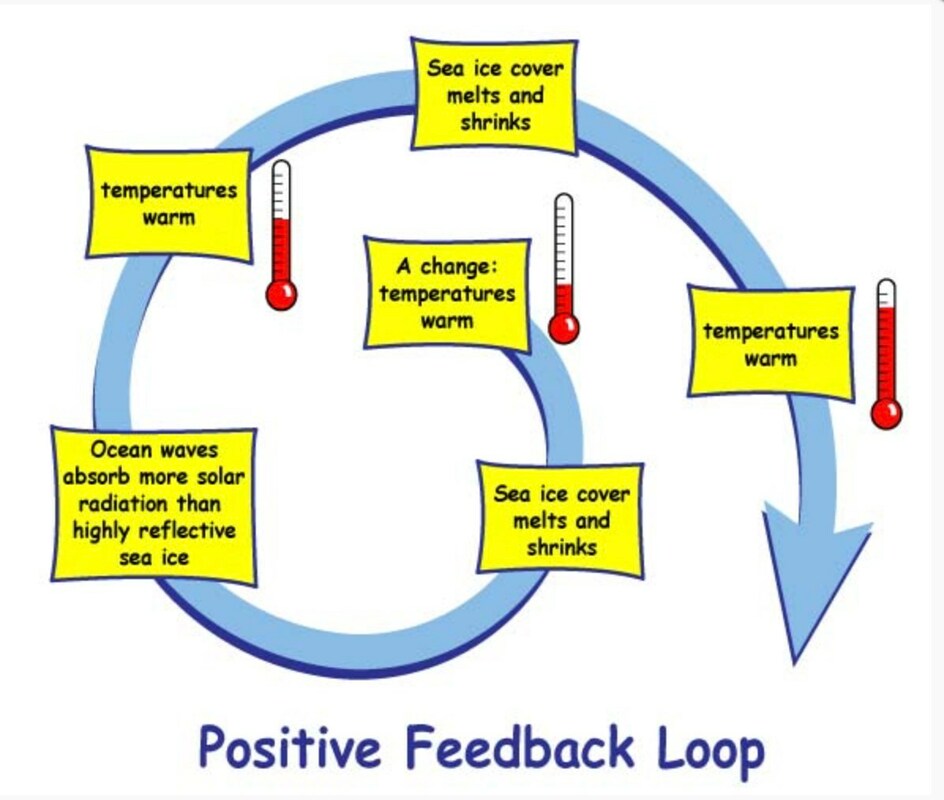

Could it be related to extreme weather patterns? As reported by The Guardian, NASA has reported that Earth's spin can slow stronger winds in El Niño years and can slow down the planet's spin. Likewise, the melting of ice caps moves matter around on Earth and thus can change the rate of spin.

While this minor time-suck has little affect on our everyday life, some scientists have called for the introduction of a negative "leap second," which would subtract one second from a day to keep the world on track for the atomic time system, if the trend continues. Since 1972, leap seconds have been added every fews years. The last one was added in 2016.

"It's quite possible that a negative leap second will be needed if the Earth's rotation rate increases further, but it's too early to say if this is likely to happen," physicist Peter Whibberley of the National Physics Laboratory in the U.K., told The Telegraph. "There are also international discussions taking place about the future of leap seconds, and it's also possible that the need for a negative leap second might push the decision towards ending leap seconds for good."

On June 29, 2022, the Earth made one full rotation that took 1.59 milliseconds less than the average day length of 86,400 seconds, or 24 hours. While a 1.59 millisecond shortening might not seem like much, it is part of a larger and peculiar trend.

Indeed, on July 26, 2022, another new record was nearly set when the Earth finished its day 1.50 milliseconds shorter than usual, as reported by The Guardian and the time-tracking website Time and Date. Time and Date notes that the year 2020 had the highest number of short days since scientists started using atomic clocks to take daily measurements in the 1960s. Scientists first started to notice the trend in 2016.

While the length of an average day may vary slightly in the short-term, in the long-term the length of the day has been increasing since the Earth-moon system was formed. That's because over time, the force of gravity has moved energy from the Earth — via the tides — to the Moon, pushing it slightly further away from us. Meanwhile, because the two bodies are in tidal lock — meaning the Moon's rate of rotation and revolution are equivalent such that we only ever see one of its sides — physics dictates that the Earth's day must lengthen if the two bodies are to remain in tidal lock as the moon moves further away. Billions of years ago, the Moon was much closer and the length of Earth's day much shorter.

While scientists know that the Earth's days are shortening on a short-term scale, a definitive reason as to why remains unclear— along with the effect it might have on how we as humans track time.

"The rotation rate of Earth is a complicated business. It has to do with exchange of angular momentum between Earth and the atmosphere and the effects of the ocean and the effect of the moon," Judah Levine, a physicist in the time and frequency division of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, told Discover Magazine. "You're not able to predict what's going to happen very far in the future."

But Fred Watson, Australia's astronomer-at-large, told ABC News in Australia that if nothing is done to stop it, "you are going to gradually get the seasons out of step with the calendar."

"When you start looking at the real nitty gritty, you realize that Earth is not just a solid ball that is spinning," Watson said. "It's got liquid on the inside, it's got liquid on the outside, and it's got an atmosphere and all of these things slosh around a bit."

Matt King from University of Tasmania described the trend to ABC News Australia as "certainly odd."

"Clearly something has changed, and changed in a way we haven't seen since the beginning of precise radio astronomy in the 1970s," King said.

Could it be related to extreme weather patterns? As reported by The Guardian, NASA has reported that Earth's spin can slow stronger winds in El Niño years and can slow down the planet's spin. Likewise, the melting of ice caps moves matter around on Earth and thus can change the rate of spin.

While this minor time-suck has little affect on our everyday life, some scientists have called for the introduction of a negative "leap second," which would subtract one second from a day to keep the world on track for the atomic time system, if the trend continues. Since 1972, leap seconds have been added every fews years. The last one was added in 2016.

"It's quite possible that a negative leap second will be needed if the Earth's rotation rate increases further, but it's too early to say if this is likely to happen," physicist Peter Whibberley of the National Physics Laboratory in the U.K., told The Telegraph. "There are also international discussions taking place about the future of leap seconds, and it's also possible that the need for a negative leap second might push the decision towards ending leap seconds for good."

ENVIRONMENT

Wait, We Can Mine Valuable Metals Using Shrubbery?

“Phytomining” is a greener way to get commodities like nickel, cobalt, thallium, and selenium.

SANDY MILNE - MOTHER JONES

AUGUST 9, 2021

Malaysia’s Kinabalu Park, which surrounds Mount Kinabalu, the 20th-largest peak in the world, is home to a nickel mine like none other. In lieu of heavy machinery, plumes of sulfur dioxide, or rivers red with runoff, you’ll find four acres of a leafy-green shrub, tended to since 2015 by local villagers. Once or twice per year, they shave off about a foot of growth from the 20-foot-tall plants. Then, they burn that crop to produce an ashy “bio-ore” that is up to 25 percent nickel by weight.

Producing metal by growing plants, or phytomining, has long been tipped as an alternative, environmentally-sustainable way to reshape—if not replace—the mining industry. Of 320,000 recognized plant species, only around 700 are so-called “hyperaccumulators,” like Kinabalu’s P. rufuschaneyi. Over time, they suck the soil dry of metals like nickel, zinc, cobalt, and even gold.

While two-thirds of nickel is used to make stainless steel, the metal is also snapped up by producers of everything from kitchenware to mobile phones, medical equipment to power generation. Zinc, on the other hand, is essential for churning out paints, rubber, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, plastics, inks, soaps, and batteries. And, as supplies of these hard-to-find metals dry up around the world, demand remains as strong as ever.

The idea of phytomining was first put forth in 1983 by an agronomist at the US Department of Agriculture named Rufus L. Chaney. Other research groups before the Malaysia team have shown that the solar-powered and carbon-neutral metal extraction process works in practice—a key step to winning over mining industry investors, who have insisted on field trials of several acres to show proof of principle. The most recent data out of Kinabalu Park, a UNESCO-listed heritage site located on the island of Borneo, is finally turning industry heads, as they show the scales have tipped in favor of phytomining’s commercial viability.

“We can now demonstrate that metal farms can produce between 170 to 280 pounds per acre annually,” said Antony van der Ent, a senior research fellow at Australia’s University of Queensland whose thesis work spurred the Malaysia trial. At the midpoint of that range, a farmer would net a cool $3,800 per acre of nickel at today’s prices--which, van der Ent added, is “on par with some of the best-performing agricultural crops on fertile soils, while operating costs are similar.”

Take, for instance, palm oil – a crop as notorious for its profitability as its role in driving deforestation in Asia and Africa. Farmers planting oil palm trees, prior to the pandemic, stood to clear 3.12 tons of crude oil annually on average--or $2,710 in today’s prices. For farmers in Malaysia and Indonesia, where 90 percent of the world’s palm oil is grown, nickel farming might just prove a more attractive option.

“At this stage, phytomining can go full-scale for nickel immediately, while phytomining for cobalt, thallium, and selenium is within reach,” van der Ent said.

While van der Ent’s team has won over some in the mining industry, adoption of phytomining isn’t yet on the fast track. That’s despite the Malaysia plot and other examples suggesting that while plants are of course less capital intensive and more environmentally friendly than traditional mining, they are also more efficient. Still, in an industry that van der Ent characterizes as resistant to change, phytomining’s immediate future could be more as a complement to traditional mining than its replacement.

Several Indonesian nickel mining companies are now looking to partner with van der Ent’s Malaysia team. “We have lined up several industry partners who’ve agreed to implement trials in Indonesia,” he said. “But due to COVID, this development is currently on hold.”

When travel restrictions are lifted and borders open up, van der Ent hopes to show that there are a number of advantages to phytomining that traditional mining simply can’t offer. “There is an abundance of unconventional ores that could be unlocked through phytomining,” he said. One example is soil abundant in tropical regions that typically contain 0.5 to 1 percent nickel by weight, which is below the cut-off where a company could profitably implement conventional strip mining.

Strip mining takes place in thick layers of soil containing more than 1 percent nickel by weight that occur in places like Brazil, Cuba, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Caledonia, the French territory in the South Pacific. This process involves removing a layer of soil or rock, referred to as overburden, before mining that seam for the target metal. And it comes at great environmental cost. Because nickel is difficult to extract, the process calls for heavy machinery that runs on diesel and generates carbon, as well as large, acid-leaching installations needed to separate the metal from its ore.

Those nickel-rich soils, however, are becoming increasingly scarce—and it might well be that an undersupply eventually drives more and more companies to embrace phytomining. That, and the fact that bio-ore contains 20 to 30 percent nickel by weight, and is also more compact and cheaper to transport than typical ores—which hover around the one to three percent mark by weight.

Still, regardless of how the Indonesia partnerships eventually go, it’s unlikely that major mining companies will swap out strip mines for shrubbery overnight. That’s why phytoremediation, a spin-off technology which complements mining rather than replacing it, might just be the thin end of the wedge.

Currently, as strip mining happens, the surrounding topsoil becomes littered with toxic metal tailings. This layer typically has to be dug out, carted off, and sold to landfills, often at great cost to the mine operator. In the case of coal extraction, the cost of rehabilitation, for strip-mined land, averages $71,000 per acre. In the EU alone, there are an estimated 130 million acres in need of clean up. It’s a hefty bill for mining companies—and that’s if they choose to foot it at all. High-profile inquiries in Indonesia, Australia, and the US show mining companies are all too often willing to shirk rehab responsibilities.

Producing metal by growing plants, or phytomining, has long been tipped as an alternative, environmentally-sustainable way to reshape—if not replace—the mining industry. Of 320,000 recognized plant species, only around 700 are so-called “hyperaccumulators,” like Kinabalu’s P. rufuschaneyi. Over time, they suck the soil dry of metals like nickel, zinc, cobalt, and even gold.

While two-thirds of nickel is used to make stainless steel, the metal is also snapped up by producers of everything from kitchenware to mobile phones, medical equipment to power generation. Zinc, on the other hand, is essential for churning out paints, rubber, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, plastics, inks, soaps, and batteries. And, as supplies of these hard-to-find metals dry up around the world, demand remains as strong as ever.

The idea of phytomining was first put forth in 1983 by an agronomist at the US Department of Agriculture named Rufus L. Chaney. Other research groups before the Malaysia team have shown that the solar-powered and carbon-neutral metal extraction process works in practice—a key step to winning over mining industry investors, who have insisted on field trials of several acres to show proof of principle. The most recent data out of Kinabalu Park, a UNESCO-listed heritage site located on the island of Borneo, is finally turning industry heads, as they show the scales have tipped in favor of phytomining’s commercial viability.

“We can now demonstrate that metal farms can produce between 170 to 280 pounds per acre annually,” said Antony van der Ent, a senior research fellow at Australia’s University of Queensland whose thesis work spurred the Malaysia trial. At the midpoint of that range, a farmer would net a cool $3,800 per acre of nickel at today’s prices--which, van der Ent added, is “on par with some of the best-performing agricultural crops on fertile soils, while operating costs are similar.”

Take, for instance, palm oil – a crop as notorious for its profitability as its role in driving deforestation in Asia and Africa. Farmers planting oil palm trees, prior to the pandemic, stood to clear 3.12 tons of crude oil annually on average--or $2,710 in today’s prices. For farmers in Malaysia and Indonesia, where 90 percent of the world’s palm oil is grown, nickel farming might just prove a more attractive option.

“At this stage, phytomining can go full-scale for nickel immediately, while phytomining for cobalt, thallium, and selenium is within reach,” van der Ent said.

While van der Ent’s team has won over some in the mining industry, adoption of phytomining isn’t yet on the fast track. That’s despite the Malaysia plot and other examples suggesting that while plants are of course less capital intensive and more environmentally friendly than traditional mining, they are also more efficient. Still, in an industry that van der Ent characterizes as resistant to change, phytomining’s immediate future could be more as a complement to traditional mining than its replacement.

Several Indonesian nickel mining companies are now looking to partner with van der Ent’s Malaysia team. “We have lined up several industry partners who’ve agreed to implement trials in Indonesia,” he said. “But due to COVID, this development is currently on hold.”

When travel restrictions are lifted and borders open up, van der Ent hopes to show that there are a number of advantages to phytomining that traditional mining simply can’t offer. “There is an abundance of unconventional ores that could be unlocked through phytomining,” he said. One example is soil abundant in tropical regions that typically contain 0.5 to 1 percent nickel by weight, which is below the cut-off where a company could profitably implement conventional strip mining.

Strip mining takes place in thick layers of soil containing more than 1 percent nickel by weight that occur in places like Brazil, Cuba, Indonesia, the Philippines, and New Caledonia, the French territory in the South Pacific. This process involves removing a layer of soil or rock, referred to as overburden, before mining that seam for the target metal. And it comes at great environmental cost. Because nickel is difficult to extract, the process calls for heavy machinery that runs on diesel and generates carbon, as well as large, acid-leaching installations needed to separate the metal from its ore.

Those nickel-rich soils, however, are becoming increasingly scarce—and it might well be that an undersupply eventually drives more and more companies to embrace phytomining. That, and the fact that bio-ore contains 20 to 30 percent nickel by weight, and is also more compact and cheaper to transport than typical ores—which hover around the one to three percent mark by weight.

Still, regardless of how the Indonesia partnerships eventually go, it’s unlikely that major mining companies will swap out strip mines for shrubbery overnight. That’s why phytoremediation, a spin-off technology which complements mining rather than replacing it, might just be the thin end of the wedge.

Currently, as strip mining happens, the surrounding topsoil becomes littered with toxic metal tailings. This layer typically has to be dug out, carted off, and sold to landfills, often at great cost to the mine operator. In the case of coal extraction, the cost of rehabilitation, for strip-mined land, averages $71,000 per acre. In the EU alone, there are an estimated 130 million acres in need of clean up. It’s a hefty bill for mining companies—and that’s if they choose to foot it at all. High-profile inquiries in Indonesia, Australia, and the US show mining companies are all too often willing to shirk rehab responsibilities.

A slowing current system in the Atlantic Ocean spells trouble for Earth

The potential disruption of an Atlantic current system marks a "big gamble at planetary scale"

By MATTHEW ROZSA - salon

PUBLISHED JUNE 5, 2021 2:00PM (EDT)

It was a seamless synthesis of science and art, expanding the frontiers of human knowledge while being eerily beautiful at the same time. That was the response when, in the 1960s, professor Henry Stommel, a pioneering oceanographer, introduced a model to his colleagues that explained the motions of ocean waters. Decades later, Dr. Michael E. Mann, a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University, still marvels at what he describes as the "elegant" nature of Stommel's model.

"It consisted of two boxes, a cold fresh box at high latitudes and a warm salty box at low latitudes, to represent the North Atlantic ocean," Mann told Salon by email. "He showed that this simple model predicted an overturning 'thermohaline' circulation — a circulation driven by contrasts in ocean water density due to both temperature and salinity, each of which influence water density."

Thus, armed with a model so simple that it can be solved with algebra, scientists now understood the ocean currents in the Atlantic.

This is how scientists figured out what is called the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or "AMOC" for short. When it comes to the motion of the ocean, AMOC is essentially a complex system of conveyor belts. The first belt contains warm water that flows north, where it cools, evaporates and increases the salinity of the ocean water. That water then cools, sinks and flows south, creating a second major belt. These currents are connected to each other by regions in the Nordic Sea, Labrador Sea and Southern Ocean, keeping sea levels down on the United States' eastern seaboard and warming up the weather in Europe.

This current system connects many different pieces of life on Earth: tides, hurricanes, sea levels, ocean life, salinity, fisheries, water pollution, temperatures, weather — all are affected by this current system. A sudden shift in how the Atlantic current system works would drastically change life on Earth.

Yet the more we learn about ocean currents, the more we have cause for alarm. A February study published in the journal Nature Geoscience reconstructed the history of the current going back 1,600 years and found that circulation is weaker now than at any other point in that span. They identified the most likely culprit as global warming. With the Greenland Ice Sheet and Arctic ice melting as the planet heats up, and rain and snow levels increasing, the water flowing north loses much of its salinity and density. This causes the water to flow south more slowly and weakens AMOC overall.

More recently, another study in the journal Nature Geoscience that identified the important role played by winds in causing changes in ocean circulation. As lead author Dr. Yavor Kostov of the University of Exeter said in a press release, scientists have struggled to understand the variability in AMOC because there are so many variables that have an effect on it. He noted that after learning that winds influenced circulation in both sub-tropical and sub-polar locations, scientists concluded that "as the climate continues to change, more efforts should be concentrated on monitoring those winds — especially in key regions on continental boundaries and the eastern coast of Greenland — and understanding what drives changes in them."

The obvious question, then, is: what will happen if climate change continues to weaken AMOC?

"This won't lead to another ice age (like 'The Day After Tomorrow,' which is a caricature of the science), but it may well threaten fish populations and lead to accelerated sea level rise along the U.S. east coast," Mann told Salon. "This is furthermore a reminder that there are surprises in the greenhouse, and often they are unwelcome ones. If we want to avoid more and more of these unwelcome surprises, we need to bring carbon emissions down dramatically in the years ahead."

Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished senior scientist at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, told Salon by email that if AMOC stopped moving heat northwards, the topical Atlantic would get much warmer. That in turn would lead to more frequent and devastating hurricanes, even as Iceland and parts of Europe cool immensely.

"AMOC acts as a relief valve for the Atlantic heat buildup in the tropics," Trenberth explained. "In the Pacific there is no equivalent and the relief valve is ENSO," which stands for "El Niño and the Southern Oscillation."

Ken Caldeira, an atmospheric scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science's Department of Global Ecology, said that it is ultimately impossible to predict with certainty what will happen if AMOC slows down — but that it is very unlikely to be good.

"For me, it is not so much about the direct impacts of this particular change, which I think are highly uncertain, but rather if we are impacting major parts of planetary-scale processes and knocking them out of the range that they operated in (and we adapted to) over the entirety of human history, it is a pretty safe bet that we can anticipate some fairly nasty unknown unknowns," Caldeira wrote to Salon. "That may be just indefensible bias that cannot be rigorously supported, but I for one am not up for big gambles at planetary scale."

"It consisted of two boxes, a cold fresh box at high latitudes and a warm salty box at low latitudes, to represent the North Atlantic ocean," Mann told Salon by email. "He showed that this simple model predicted an overturning 'thermohaline' circulation — a circulation driven by contrasts in ocean water density due to both temperature and salinity, each of which influence water density."

Thus, armed with a model so simple that it can be solved with algebra, scientists now understood the ocean currents in the Atlantic.

This is how scientists figured out what is called the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or "AMOC" for short. When it comes to the motion of the ocean, AMOC is essentially a complex system of conveyor belts. The first belt contains warm water that flows north, where it cools, evaporates and increases the salinity of the ocean water. That water then cools, sinks and flows south, creating a second major belt. These currents are connected to each other by regions in the Nordic Sea, Labrador Sea and Southern Ocean, keeping sea levels down on the United States' eastern seaboard and warming up the weather in Europe.

This current system connects many different pieces of life on Earth: tides, hurricanes, sea levels, ocean life, salinity, fisheries, water pollution, temperatures, weather — all are affected by this current system. A sudden shift in how the Atlantic current system works would drastically change life on Earth.

Yet the more we learn about ocean currents, the more we have cause for alarm. A February study published in the journal Nature Geoscience reconstructed the history of the current going back 1,600 years and found that circulation is weaker now than at any other point in that span. They identified the most likely culprit as global warming. With the Greenland Ice Sheet and Arctic ice melting as the planet heats up, and rain and snow levels increasing, the water flowing north loses much of its salinity and density. This causes the water to flow south more slowly and weakens AMOC overall.

More recently, another study in the journal Nature Geoscience that identified the important role played by winds in causing changes in ocean circulation. As lead author Dr. Yavor Kostov of the University of Exeter said in a press release, scientists have struggled to understand the variability in AMOC because there are so many variables that have an effect on it. He noted that after learning that winds influenced circulation in both sub-tropical and sub-polar locations, scientists concluded that "as the climate continues to change, more efforts should be concentrated on monitoring those winds — especially in key regions on continental boundaries and the eastern coast of Greenland — and understanding what drives changes in them."

The obvious question, then, is: what will happen if climate change continues to weaken AMOC?

"This won't lead to another ice age (like 'The Day After Tomorrow,' which is a caricature of the science), but it may well threaten fish populations and lead to accelerated sea level rise along the U.S. east coast," Mann told Salon. "This is furthermore a reminder that there are surprises in the greenhouse, and often they are unwelcome ones. If we want to avoid more and more of these unwelcome surprises, we need to bring carbon emissions down dramatically in the years ahead."

Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished senior scientist at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, told Salon by email that if AMOC stopped moving heat northwards, the topical Atlantic would get much warmer. That in turn would lead to more frequent and devastating hurricanes, even as Iceland and parts of Europe cool immensely.

"AMOC acts as a relief valve for the Atlantic heat buildup in the tropics," Trenberth explained. "In the Pacific there is no equivalent and the relief valve is ENSO," which stands for "El Niño and the Southern Oscillation."

Ken Caldeira, an atmospheric scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science's Department of Global Ecology, said that it is ultimately impossible to predict with certainty what will happen if AMOC slows down — but that it is very unlikely to be good.

"For me, it is not so much about the direct impacts of this particular change, which I think are highly uncertain, but rather if we are impacting major parts of planetary-scale processes and knocking them out of the range that they operated in (and we adapted to) over the entirety of human history, it is a pretty safe bet that we can anticipate some fairly nasty unknown unknowns," Caldeira wrote to Salon. "That may be just indefensible bias that cannot be rigorously supported, but I for one am not up for big gambles at planetary scale."

Forest the size of France regrown worldwide over 20 years, study finds

Nearly 59m hectares of forests have regrown since 2000, showing that regeneration in some places is paying off

Oliver Milman in New York

the guardian

Tue 11 May 2021 11.13 EDT

An area of forest the size of France has regrown around the world over the past 20 years, showing that regeneration in some places is paying off, a new analysis has found.

Nearly 59m hectares of forests have regrown since 2000, the research found, providing the potential to soak up and store 5.9 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide – more than the annual emissions of the entire US.

The two-year study, conducted via satellite imaging data and on-ground surveys across dozens of countries, identified areas of regrowth in the Atlantic forest in Brazil, where an area the size of the Netherlands has rebounded since 2000 due to conservation efforts and altered industry practices.

Another regrowth area is found in the boreal forests of Mongolia, where 1.2m hectares of forest have regenerated in two decades due to the work of conservationists and the Mongolian government. Forests also made a comeback in parts of central Africa and Canada.

However, the world is still experiencing an overall loss of forests “at a terrifying rate”, the researchers warned, with deforestation occurring much faster than restoration schemes.

Over a similar period outlined in the regrowth study, which was led by WWF as part of the Trillion Trees project, 386m hectares of tree cover were lost worldwide, around seven times the area of regenerated forest.

Previous studies have estimated that an area of forest as large as the UK is being lost each year, largely for timber or to make way for agriculture, such deforestation posing huge threats to wildlife and efforts to contain the climate crisis.

Deforestation spiked sharply last year, with losses concentrated in the vital rainforests in tropical areas.

Trees are being felled and burned at a rapid rate in the Amazon, with more than 430,000 acres already lost in 2021. Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president, has come under increasing international pressure over such deforestation.

“The science is clear – if we are to avoid dangerous climate change and turn around the loss of nature, we must both halt deforestation and restore natural forests,” said William Baldwin-Cantello, director of nature-based solutions at WWF.

“We’ve known for a long time that natural forest regeneration is often cheaper, richer in carbon and better for biodiversity than actively planted forests, and this research tells us where and why regeneration is happening, and how we can recreate those conditions elsewhere.

“But we can’t take this regeneration for granted – deforestation still claims millions of hectares every year, vastly more than is regenerated.”

Nearly 59m hectares of forests have regrown since 2000, the research found, providing the potential to soak up and store 5.9 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide – more than the annual emissions of the entire US.

The two-year study, conducted via satellite imaging data and on-ground surveys across dozens of countries, identified areas of regrowth in the Atlantic forest in Brazil, where an area the size of the Netherlands has rebounded since 2000 due to conservation efforts and altered industry practices.

Another regrowth area is found in the boreal forests of Mongolia, where 1.2m hectares of forest have regenerated in two decades due to the work of conservationists and the Mongolian government. Forests also made a comeback in parts of central Africa and Canada.

However, the world is still experiencing an overall loss of forests “at a terrifying rate”, the researchers warned, with deforestation occurring much faster than restoration schemes.

Over a similar period outlined in the regrowth study, which was led by WWF as part of the Trillion Trees project, 386m hectares of tree cover were lost worldwide, around seven times the area of regenerated forest.

Previous studies have estimated that an area of forest as large as the UK is being lost each year, largely for timber or to make way for agriculture, such deforestation posing huge threats to wildlife and efforts to contain the climate crisis.

Deforestation spiked sharply last year, with losses concentrated in the vital rainforests in tropical areas.

Trees are being felled and burned at a rapid rate in the Amazon, with more than 430,000 acres already lost in 2021. Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president, has come under increasing international pressure over such deforestation.

“The science is clear – if we are to avoid dangerous climate change and turn around the loss of nature, we must both halt deforestation and restore natural forests,” said William Baldwin-Cantello, director of nature-based solutions at WWF.

“We’ve known for a long time that natural forest regeneration is often cheaper, richer in carbon and better for biodiversity than actively planted forests, and this research tells us where and why regeneration is happening, and how we can recreate those conditions elsewhere.

“But we can’t take this regeneration for granted – deforestation still claims millions of hectares every year, vastly more than is regenerated.”

THE MOVIE 'DAY AFTER TOMORROW' WAS RIGHT!!!

Atlantic Ocean circulation at weakest in a millennium, say scientists

Decline in system underpinning Gulf Stream could lead to more extreme weather in Europe and higher sea levels on US east coast

Fiona Harvey Environment correspondent

THE GUARDIAN

Thu 25 Feb 2021 11.00 EST

The Atlantic Ocean circulation that underpins the Gulf Stream, the weather system that brings warm and mild weather to Europe, is at its weakest in more than a millennium, and climate breakdown is the probable cause, according to new data.

Further weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) could result in more storms battering the UK, more intense winters and an increase in damaging heatwaves and droughts across Europe.

Scientists predict that the AMOC will weaken further if global heating continues, and could reduce by about 34% to 45% by the end of this century, which could bring us close to a “tipping point” at which the system could become irrevocably unstable. A weakened Gulf Stream would also raise sea levels on the Atlantic coast of the US, with potentially disastrous consequences.

Stefan Rahmstorf, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who co-authored the study published on Thursday in Nature Geoscience, told the Guardian that a weakening AMOC would increase the number and severity of storms hitting Britain, and bring more heatwaves to Europe.

He said the circulation had already slowed by about 15%, and the impacts were being seen. “In 20 to 30 years it is likely to weaken further, and that will inevitably influence our weather, so we would see an increase in storms and heatwaves in Europe, and sea level rises on the east coast of the US,” he said.

Rahmstorf and scientists from Maynooth University in Ireland and University College London in the UK concluded that the current weakening had not been seen over at least the last 1,000 years, after studying sediments, Greenland ice cores and other proxy data that revealed past weather patterns over that time. The AMOC has only been measured directly since 2004.

The AMOC is one of the world’s biggest ocean circulation systems, carrying warm surface water from the Gulf of Mexico towards the north Atlantic, where it cools and becomes saltier until it sinks north of Iceland, which in turn pulls more warm water from the Caribbean. This circulation is accompanied by winds that also help to bring mild and wet weather to Ireland, the UK and other parts of western Europe.

Scientists have long predicted a weakening of the AMOC as a result of global heating, and have raised concerns that it could collapse altogether. The new study found that any such point was likely to be decades away, but that continued high greenhouse gas emissions would bring it closer.

---

The AMOC is a large part of the Gulf Stream, often described as the “conveyor belt” that brings warm water from the equator. But the bigger weather system would not break down entirely if the ocean circulation became unstable, because winds also play a key role. The circulation has broken down before, in different circumstances, for instance at the end of the last ice age.

The Gulf Stream is separate from the jet stream that has helped to bring extreme weather to the northern hemisphere in recent weeks, though like the jet stream it is also affected by the rising temperatures in the Arctic. Normally, the very cold temperatures over the Arctic create a polar vortex that keeps a steady jet stream of air currents keeping that cold air in place. But higher temperatures over the Arctic have resulted in a weak and wandering jet stream, which has helped cold weather to spread much further south in some cases, while bringing warmer weather further north in others, contributing to the extremes in weather seen in the UK, Europe and the US in recent weeks.

Similarly, the Gulf Stream is affected by the melting of Arctic ice, which dumps large quantities of cold water to the south of Greenland, disrupting the flow of the AMOC. The impacts of variations in the Gulf Stream are seen over much longer periods than variations in the jet stream, but will also bring more extreme weather as the climate warms.

---

“While the AMOC won’t collapse any time soon, the authors warn that the current could become unstable by the end of this century if warming continues unabated,” he said. “It has already been increasing the risk for stronger hurricanes at the US east coast due to warmer ocean waters, as well as potentially altering circulation patterns over western Europe.”

Further weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) could result in more storms battering the UK, more intense winters and an increase in damaging heatwaves and droughts across Europe.

Scientists predict that the AMOC will weaken further if global heating continues, and could reduce by about 34% to 45% by the end of this century, which could bring us close to a “tipping point” at which the system could become irrevocably unstable. A weakened Gulf Stream would also raise sea levels on the Atlantic coast of the US, with potentially disastrous consequences.

Stefan Rahmstorf, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who co-authored the study published on Thursday in Nature Geoscience, told the Guardian that a weakening AMOC would increase the number and severity of storms hitting Britain, and bring more heatwaves to Europe.

He said the circulation had already slowed by about 15%, and the impacts were being seen. “In 20 to 30 years it is likely to weaken further, and that will inevitably influence our weather, so we would see an increase in storms and heatwaves in Europe, and sea level rises on the east coast of the US,” he said.

Rahmstorf and scientists from Maynooth University in Ireland and University College London in the UK concluded that the current weakening had not been seen over at least the last 1,000 years, after studying sediments, Greenland ice cores and other proxy data that revealed past weather patterns over that time. The AMOC has only been measured directly since 2004.

The AMOC is one of the world’s biggest ocean circulation systems, carrying warm surface water from the Gulf of Mexico towards the north Atlantic, where it cools and becomes saltier until it sinks north of Iceland, which in turn pulls more warm water from the Caribbean. This circulation is accompanied by winds that also help to bring mild and wet weather to Ireland, the UK and other parts of western Europe.

Scientists have long predicted a weakening of the AMOC as a result of global heating, and have raised concerns that it could collapse altogether. The new study found that any such point was likely to be decades away, but that continued high greenhouse gas emissions would bring it closer.

---

The AMOC is a large part of the Gulf Stream, often described as the “conveyor belt” that brings warm water from the equator. But the bigger weather system would not break down entirely if the ocean circulation became unstable, because winds also play a key role. The circulation has broken down before, in different circumstances, for instance at the end of the last ice age.

The Gulf Stream is separate from the jet stream that has helped to bring extreme weather to the northern hemisphere in recent weeks, though like the jet stream it is also affected by the rising temperatures in the Arctic. Normally, the very cold temperatures over the Arctic create a polar vortex that keeps a steady jet stream of air currents keeping that cold air in place. But higher temperatures over the Arctic have resulted in a weak and wandering jet stream, which has helped cold weather to spread much further south in some cases, while bringing warmer weather further north in others, contributing to the extremes in weather seen in the UK, Europe and the US in recent weeks.

Similarly, the Gulf Stream is affected by the melting of Arctic ice, which dumps large quantities of cold water to the south of Greenland, disrupting the flow of the AMOC. The impacts of variations in the Gulf Stream are seen over much longer periods than variations in the jet stream, but will also bring more extreme weather as the climate warms.

---

“While the AMOC won’t collapse any time soon, the authors warn that the current could become unstable by the end of this century if warming continues unabated,” he said. “It has already been increasing the risk for stronger hurricanes at the US east coast due to warmer ocean waters, as well as potentially altering circulation patterns over western Europe.”

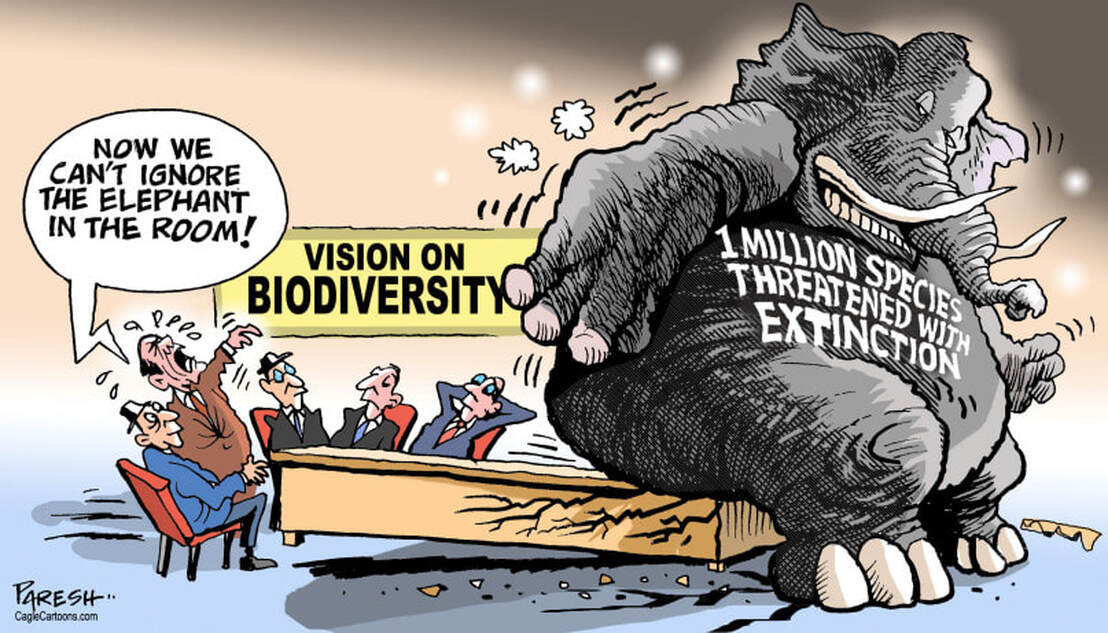

Biodiversity

Fifth of countries at risk of ecosystem collapse, analysis finds

Trillions of dollars of GDP depend on biodiversity, according to Swiss Re report

Damian Carrington Environment editor

the guardian

Mon 12 Oct 2020 05.12 EDT

One-fifth of the world’s countries are at risk of their ecosystems collapsing because of the destruction of wildlife and their habitats, according to an analysis by the insurance firm Swiss Re.

Natural “services” such as food, clean water and air, and flood protection have already been damaged by human activity.

More than half of global GDP – $42tn (£32tn) – depends on high-functioning biodiversity, according to the report, but the risk of tipping points is growing.

Countries including Australia, Israel and South Africa rank near the top of Swiss Re’s index of risk to biodiversity and ecosystem services, with India, Spain and Belgium also highlighted. Countries with fragile ecosystems and large farming sectors, such as Pakistan and Nigeria, are also flagged up.

Countries including Brazil and Indonesia had large areas of intact ecosystems but had a strong economic dependence on natural resources, which showed the importance of protecting their wild places, Swiss Re said.

“A staggering fifth of countries globally are at risk of their ecosystems collapsing due to a decline in biodiversity and related beneficial services,” said Swiss Re, one of the world’s biggest reinsurers and a linchpin of the global insurance industry.

“If the ecosystem service decline goes on [in countries at risk], you would see then scarcities unfolding even more strongly, up to tipping points,” said Oliver Schelske, lead author of the research.

Jeffrey Bohn, Swiss Re’s chief research officer, said: “This is the first index to our knowledge that pulls together indicators of biodiversity and ecosystems to cross-compare around the world, and then specifically link back to the economies of those locations.”

The index was designed to help insurers assess ecosystem risks when setting premiums for businesses but Bohn said it could have a wider use as it “allows businesses and governments to factor biodiversity and ecosystems into their economic decision-making”.

The UN revealed in September that the world’s governments failed to meet a single target to stem biodiversity losses in the last decade, while leading scientists warned in 2019 that humans were in jeopardy from the accelerating decline of the Earth’s natural life-support systems. More than 60 national leaders recently pledged to end the destruction.

The Swiss Re index is built on 10 key ecosystem services identified by the world’s scientists and uses scientific data to map the state of these services at a resolution of one square kilometre across the world’s land. The services include provision of clean water and air, food, timber, pollination, fertile soil, erosion control, and coastal protection, as well as a measure of habitat intactness.

Those countries with more than 30% of their area found to have fragile ecosystems were deemed to be at risk of those ecosystems collapsing. Just one in seven countries had intact ecosystems covering more than 30% of their country area.

Among the G20 leading economies, South Africa and Australia were seen as being most at risk, with China 7th, the US 9th and the UK 16th.

Alexander Pfaff, a professor of public policy, economics and environment at Duke University in the US, said: “Societies, from local to global, can do much better when we not only acknowledge the importance of contributions from nature – as this index is doing – but also take that into account in our actions, private and public.”

Pfaff said it was important to note that the economic impacts of the degradation of nature began well before ecosystem collapse, adding: “Naming a problem may well be half the solution, [but] the other half is taking action.”

Swiss Re said developing and developed countries were at risk from biodiversity loss. Water scarcity, for example, could damage manufacturing sectors, properties and supply chains.

Bohn said about 75% of global assets were not insured, partly because of insufficient data. He said the index could help quantify risks such as crops losses and flooding.

Natural “services” such as food, clean water and air, and flood protection have already been damaged by human activity.

More than half of global GDP – $42tn (£32tn) – depends on high-functioning biodiversity, according to the report, but the risk of tipping points is growing.

Countries including Australia, Israel and South Africa rank near the top of Swiss Re’s index of risk to biodiversity and ecosystem services, with India, Spain and Belgium also highlighted. Countries with fragile ecosystems and large farming sectors, such as Pakistan and Nigeria, are also flagged up.

Countries including Brazil and Indonesia had large areas of intact ecosystems but had a strong economic dependence on natural resources, which showed the importance of protecting their wild places, Swiss Re said.

“A staggering fifth of countries globally are at risk of their ecosystems collapsing due to a decline in biodiversity and related beneficial services,” said Swiss Re, one of the world’s biggest reinsurers and a linchpin of the global insurance industry.

“If the ecosystem service decline goes on [in countries at risk], you would see then scarcities unfolding even more strongly, up to tipping points,” said Oliver Schelske, lead author of the research.

Jeffrey Bohn, Swiss Re’s chief research officer, said: “This is the first index to our knowledge that pulls together indicators of biodiversity and ecosystems to cross-compare around the world, and then specifically link back to the economies of those locations.”

The index was designed to help insurers assess ecosystem risks when setting premiums for businesses but Bohn said it could have a wider use as it “allows businesses and governments to factor biodiversity and ecosystems into their economic decision-making”.

The UN revealed in September that the world’s governments failed to meet a single target to stem biodiversity losses in the last decade, while leading scientists warned in 2019 that humans were in jeopardy from the accelerating decline of the Earth’s natural life-support systems. More than 60 national leaders recently pledged to end the destruction.

The Swiss Re index is built on 10 key ecosystem services identified by the world’s scientists and uses scientific data to map the state of these services at a resolution of one square kilometre across the world’s land. The services include provision of clean water and air, food, timber, pollination, fertile soil, erosion control, and coastal protection, as well as a measure of habitat intactness.

Those countries with more than 30% of their area found to have fragile ecosystems were deemed to be at risk of those ecosystems collapsing. Just one in seven countries had intact ecosystems covering more than 30% of their country area.

Among the G20 leading economies, South Africa and Australia were seen as being most at risk, with China 7th, the US 9th and the UK 16th.

Alexander Pfaff, a professor of public policy, economics and environment at Duke University in the US, said: “Societies, from local to global, can do much better when we not only acknowledge the importance of contributions from nature – as this index is doing – but also take that into account in our actions, private and public.”

Pfaff said it was important to note that the economic impacts of the degradation of nature began well before ecosystem collapse, adding: “Naming a problem may well be half the solution, [but] the other half is taking action.”

Swiss Re said developing and developed countries were at risk from biodiversity loss. Water scarcity, for example, could damage manufacturing sectors, properties and supply chains.

Bohn said about 75% of global assets were not insured, partly because of insufficient data. He said the index could help quantify risks such as crops losses and flooding.

Satellite images show rapid growth of glacial lakes worldwide

Number of glacial lakes rose by 53% in 1990-2018 to reveal impact of increased meltwater

Ian Sample Science editor

the guardian

Mon 31 Aug 2020 11.00 EDT

Glacial lakes have grown rapidly around the world in recent decades, according to satellite images that reveal the impact of increased meltwater draining off retreating glaciers.

Scientists analysed more than quarter of a million satellite images to assess how lakes formed by melting glaciers have been affected by global heating and other processes.

The images show the number of glacial lakes rose by 53% between 1990 and 2018, expanding the amount of the Earth the lakes cover by about 51%. According to the survey, 14,394 glacial lakes spread over nearly 9,000 square km of the planet’s surface.

Based on the figures, the researchers estimate the volume of the world’s glacial lakes grew by 48% over the same period and now hold 156.5 cubic km of water.

“Our findings show how quickly Earth surface systems are responding to climate change, and the global nature of this,” said Stephan Harrison, a professor of climate and environmental change at Exeter University. “More importantly, our results help to fill a gap in the science because, until now, it was not known how much water was held in the world’s glacial lakes.”

Glacial lakes are an important source of fresh water for many of the world’s poorest people, particularly in the mountains of Asia and parts of South America. But the lakes also present a growing threat from outburst floods that can tear down villages, wash away roads and destroy pipelines and other infrastructure.

The fastest-growing lakes are in Scandinavia, Iceland and Russia, which more than doubled in area over the study period. Because many of the lakes are relatively small, the rise in volume is not substantial on a global level.

Elsewhere, such as in Patagonia and Alaska, glacial lakes grew more slowly, at about 80%, but many of the lakes in these regions are vast, making the absolute increase in water volume huge.

According to the report, published in Nature Climate Change, three of the largest Patagonian lakes grew at a much slower rate, but still reached 3,582 square km in 2018, up 27 square km since 1990.

In other regions, the picture was more variable. In the north of Greenland, glacial lakes were growing rapidly, in line with global heating being more extreme in the Arctic. In south-west Greenland, some glacial lakes had shrunk, but often this was because they had already drained.

Though meltwater is crucial for many communities living in valleys beneath glaciers, sudden outbursts from glacial lakes can be devastating. Writing in the journal, the scientists highlight particular threats to hydroelectric power plants in the Himalayas; the Trans-Alaska pipeline, which traverses mountains hosting glacial lakes; major roadways such as the Karakoram highway between China and Pakistan, a corridor that carries billions of dollars of goods annually.

“As lakes get bigger there is more water in them to drain quickly and produce glacial lake outburst floods,” Harrison said. “These are a real hazard in many valleys connected to retreating glaciers in parts of the Himalayas and Andes, for example.

“Such glacial lake outburst floods, or GLOFs, have killed tens of thousands of people over the past century and destroyed valuable infrastructure such as hydroelectric power schemes. However, this is a complex issue. Some lakes become less vulnerable to GLOF triggers as they get bigger, but the more water that is available will tend to make the GLOF worse if one occurs.”

Scientists analysed more than quarter of a million satellite images to assess how lakes formed by melting glaciers have been affected by global heating and other processes.

The images show the number of glacial lakes rose by 53% between 1990 and 2018, expanding the amount of the Earth the lakes cover by about 51%. According to the survey, 14,394 glacial lakes spread over nearly 9,000 square km of the planet’s surface.

Based on the figures, the researchers estimate the volume of the world’s glacial lakes grew by 48% over the same period and now hold 156.5 cubic km of water.

“Our findings show how quickly Earth surface systems are responding to climate change, and the global nature of this,” said Stephan Harrison, a professor of climate and environmental change at Exeter University. “More importantly, our results help to fill a gap in the science because, until now, it was not known how much water was held in the world’s glacial lakes.”

Glacial lakes are an important source of fresh water for many of the world’s poorest people, particularly in the mountains of Asia and parts of South America. But the lakes also present a growing threat from outburst floods that can tear down villages, wash away roads and destroy pipelines and other infrastructure.

The fastest-growing lakes are in Scandinavia, Iceland and Russia, which more than doubled in area over the study period. Because many of the lakes are relatively small, the rise in volume is not substantial on a global level.

Elsewhere, such as in Patagonia and Alaska, glacial lakes grew more slowly, at about 80%, but many of the lakes in these regions are vast, making the absolute increase in water volume huge.

According to the report, published in Nature Climate Change, three of the largest Patagonian lakes grew at a much slower rate, but still reached 3,582 square km in 2018, up 27 square km since 1990.

In other regions, the picture was more variable. In the north of Greenland, glacial lakes were growing rapidly, in line with global heating being more extreme in the Arctic. In south-west Greenland, some glacial lakes had shrunk, but often this was because they had already drained.

Though meltwater is crucial for many communities living in valleys beneath glaciers, sudden outbursts from glacial lakes can be devastating. Writing in the journal, the scientists highlight particular threats to hydroelectric power plants in the Himalayas; the Trans-Alaska pipeline, which traverses mountains hosting glacial lakes; major roadways such as the Karakoram highway between China and Pakistan, a corridor that carries billions of dollars of goods annually.

“As lakes get bigger there is more water in them to drain quickly and produce glacial lake outburst floods,” Harrison said. “These are a real hazard in many valleys connected to retreating glaciers in parts of the Himalayas and Andes, for example.

“Such glacial lake outburst floods, or GLOFs, have killed tens of thousands of people over the past century and destroyed valuable infrastructure such as hydroelectric power schemes. However, this is a complex issue. Some lakes become less vulnerable to GLOF triggers as they get bigger, but the more water that is available will tend to make the GLOF worse if one occurs.”

A methane leak in Antarctica provides new insight into how methane-eating microbes evolve

These ocean-dwelling methane-hungry microbes are one of Earth's great hopes for mitigating global warming

MATTHEW ROZSA - salon

JULY 24, 2020 10:11PM (UTC)

Deep underwater in the Ross Sea off the coast of Antarctica, scientists have discovered a new active leak of methane, a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide. The discovery marked the first time that scientists were able to directly observe a new underwater methane seep, and see how methane-eating microbial life in its proximity evolved over a five-year span.

In a study published in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a research team led by Oregon State University oceanographer Dr. Andrew Thurber explained that the methane gas leak was first discovered in 2011 off Antarctic shores. Antarctica is believed to have as much as a quarter of the planet's ocean-based methane trapped in permafrost and on the continental shelves.

Just as micro-organisms like fungi breed like crazy in the presence of a food source in our homes — say, an open soda can or jam jar left out in the open — methane-eating microbes are present in small numbers spread throughout Earth's oceans, and only multiply precipitously when they find a prominent "food" source like a methane seep. Indeed, the scientists note that by 2016, methane-consuming micro-organisms began appearing by the leak and consuming a small portion of the gas, though not enough to offset the methane venting.

In the case of this Ross Sea methane seep, researchers sought to quantify the "response rate" of the microbial community over time — in other words, how fast these microbes took up residence around the seep, and how much methane they took in before it could reach the atmosphere. Five years after the seep's formation, researchers noted that the microbial mat "had not yet formed a sufficient filter to mitigate the release of methane from the sediment."

The discovery is particularly interesting in that the chronology of these kinds of phenomena is not well-understood; prior to this paper, it was unknown how long microbial life would take to filter methane in a similar methane seep. The researchers said that five years after the seep's forming, the microbes were still in an "early successional stage."

"This study provides the first report of the evolution of a seep system from a non-seep environment, and reveals that the rate of microbial succession may have an unrealized impact on greenhouse gas emission from marine methane reservoirs," they wrote.

The presence of methane increases the amount of heat trapped in the atmosphere. From a warming perspective, it is preferably that microbes consume the methane first and produce carbon dioxide — which is still a greenhouse gas, though not nearly as potent as methane, which absorbs 25 times more heat in the atmosphere compared to carbon dioxide.

"Our results suggest that the accuracy of future global climate models may be improved by considering the time it will take for microbial communities to respond to novel methane input," the authors write.

Salon reached out to a pair of climatologists for their thoughts on the study. The common observation, which was made in the study itself, is that the methane leak itself did not appear to have occurred strictly because of global warming, though that is a scenario that scientists are actively concerned about.

"This study really just demonstrates a potential pathway by which Antarctic marine methane can escape to the atmosphere," Dr. Michael E. Mann, a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University, told Salon by email. "It doesn't demonstrate that climate change has lead to any increase in methane emissions. Relevant to this latter point is a study that just came out a week showing that methane increases in the atmosphere are due to natural gas extraction ('fracking') and livestock methane emissions. There is no evidence that 'methane feedbacks' are contributing to rising methane, at least not presently."

Dr. Kevin Trenberth, a a Distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, made a similar point in an email to Salon.

"Methane concentrations in the atmosphere have increased prominently in the past few years, and a significant source is from leaky fracking installations and the resulting fugitive emissions," Trenberth explained. After reviewing the economics of fracking during the coronavirus pandemic — and in particular how some of the industry has gone bust — Trenberth responded to the paper by writing that it "illuminates largely natural processes in the southern ocean. Carbon of various sorts (wood, sea weed, etc) decays and forms either carbon dioxide (if aerobic) or methane (if anaerobic and immersed in water). Certain different kinds of bacteria flourish under both conditions. My understanding is that a lot of methane from depth in the ocean is absorbed rather than emitted into the atmosphere. That would be a key question."

He added, "What surprises me about this article is that the southern oceans are far from friendly to work in. There are strong winds and huge waves, and how they can even accomplish this work would be of interest. . . . Are their results biased as a result? In any case, evidently rich and new biogeochemistry has been discovered and can only help understanding and modeling."

In a study published in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a research team led by Oregon State University oceanographer Dr. Andrew Thurber explained that the methane gas leak was first discovered in 2011 off Antarctic shores. Antarctica is believed to have as much as a quarter of the planet's ocean-based methane trapped in permafrost and on the continental shelves.

Just as micro-organisms like fungi breed like crazy in the presence of a food source in our homes — say, an open soda can or jam jar left out in the open — methane-eating microbes are present in small numbers spread throughout Earth's oceans, and only multiply precipitously when they find a prominent "food" source like a methane seep. Indeed, the scientists note that by 2016, methane-consuming micro-organisms began appearing by the leak and consuming a small portion of the gas, though not enough to offset the methane venting.

In the case of this Ross Sea methane seep, researchers sought to quantify the "response rate" of the microbial community over time — in other words, how fast these microbes took up residence around the seep, and how much methane they took in before it could reach the atmosphere. Five years after the seep's formation, researchers noted that the microbial mat "had not yet formed a sufficient filter to mitigate the release of methane from the sediment."

The discovery is particularly interesting in that the chronology of these kinds of phenomena is not well-understood; prior to this paper, it was unknown how long microbial life would take to filter methane in a similar methane seep. The researchers said that five years after the seep's forming, the microbes were still in an "early successional stage."

"This study provides the first report of the evolution of a seep system from a non-seep environment, and reveals that the rate of microbial succession may have an unrealized impact on greenhouse gas emission from marine methane reservoirs," they wrote.

The presence of methane increases the amount of heat trapped in the atmosphere. From a warming perspective, it is preferably that microbes consume the methane first and produce carbon dioxide — which is still a greenhouse gas, though not nearly as potent as methane, which absorbs 25 times more heat in the atmosphere compared to carbon dioxide.

"Our results suggest that the accuracy of future global climate models may be improved by considering the time it will take for microbial communities to respond to novel methane input," the authors write.

Salon reached out to a pair of climatologists for their thoughts on the study. The common observation, which was made in the study itself, is that the methane leak itself did not appear to have occurred strictly because of global warming, though that is a scenario that scientists are actively concerned about.

"This study really just demonstrates a potential pathway by which Antarctic marine methane can escape to the atmosphere," Dr. Michael E. Mann, a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University, told Salon by email. "It doesn't demonstrate that climate change has lead to any increase in methane emissions. Relevant to this latter point is a study that just came out a week showing that methane increases in the atmosphere are due to natural gas extraction ('fracking') and livestock methane emissions. There is no evidence that 'methane feedbacks' are contributing to rising methane, at least not presently."

Dr. Kevin Trenberth, a a Distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, made a similar point in an email to Salon.

"Methane concentrations in the atmosphere have increased prominently in the past few years, and a significant source is from leaky fracking installations and the resulting fugitive emissions," Trenberth explained. After reviewing the economics of fracking during the coronavirus pandemic — and in particular how some of the industry has gone bust — Trenberth responded to the paper by writing that it "illuminates largely natural processes in the southern ocean. Carbon of various sorts (wood, sea weed, etc) decays and forms either carbon dioxide (if aerobic) or methane (if anaerobic and immersed in water). Certain different kinds of bacteria flourish under both conditions. My understanding is that a lot of methane from depth in the ocean is absorbed rather than emitted into the atmosphere. That would be a key question."

He added, "What surprises me about this article is that the southern oceans are far from friendly to work in. There are strong winds and huge waves, and how they can even accomplish this work would be of interest. . . . Are their results biased as a result? In any case, evidently rich and new biogeochemistry has been discovered and can only help understanding and modeling."

greed, stupidity, and incompetence on display, again!!!

North Atlantic right whales now officially 'one step from extinction'

International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List changes ocean giants’ status to ‘critically endangered’

Claudia Geib

the guardian

Thu 16 Jul 2020 06.00 EDT

With their population still struggling to recover from over three centuries of whaling, the North Atlantic right whale is now just “one step from extinction”, according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The IUCN last week moved the whale’s status on their Red List from “endangered” to “critically endangered” – the last stop before the species is considered extinct in the wild.

The status change reflects the fact that fewer than 250 mature individuals probably remain in a population of roughly 400. While grim, scientists and conservationists expressed hope that this move may help speed up protections for these dwindling giants.

“As scientists, we’ve been working for many years under the idea that North Atlantic right whales are critically endangered,” said David Wiley, research coordinator for the Stellwagen Bank national marine sanctuary in Massachusetts. “The good thing about this new designation is it does bring them back front and center. Hopefully that will bring them up to the top of political consciousness.”

Moira Brown, senior scientist at the Canadian Whale Institute, who has been working on right whales for over 30 years, said: “For an organization like the IUCN, which weighs a lot of information when they make these changes, to shift the right whale’s status – it brings international recognition. It’s an added layer of: we’re not just blowing smoke here, this animal is really in trouble.”

Often found leisurely filtering plankton at the ocean surface, the right whale species was once highly targeted by whalers: their slow speed made them easy to hunt, and they float when killed, thanks to thick blubber.

That slow surface feeding today leads to these whales being struck by boat propellers or becoming fatally snarled in fishing gear. According to the IUCN, of the 30 deaths or serious injuries to North Atlantic right whales recorded between 2012 and 2016, 26 were caused by fishing gear entanglement.

As a result, many scientists support stricter regulations on the fishing industry, a topic that draws concern from fishing communities: new regulations could mean fishermen must bear the cost of upgrading gear, and they are often concerned that these changes will also reduce their catch. The National Marine Fisheries Service’s 2019 attempt to reduce gear in the water led the Maine Lobstermen’s Association to back out of regional protective measures.

“I think it’s sometimes portrayed as: you have whales, or you can have fishing,” said Amy Knowlton, a senior scientist at the New England Aquarium. “What we’re trying to say is you can still fish if you can do it in a safer way for the whales.”

Knowlton noted that the growing entanglement problem may be partially due to stronger ropes adopted in the 1990s, making it harder for whales to break free. She is now encouraging fishermen to use lines with a weaker breaking strength.

Climate change also plays a big role. Since 1990, the North Atlantic right whale’s primary feeding ground, the Gulf of Maine, has warmed three times faster than the rest of the world’s oceans.

The US and Canadian governments enforce seasonal boat speed limits in areas that right whales frequent. But the whales are changing their usual haunts as they seek cooler waters, taking them into places without these speed limits. Warming waters also make it harder for right whales to find food, which could explain their unusually low birth rate.

Additionally, climate change has caused a lobster boom in northern New England and eastern Canada, which has brought more fishing gear into the whale’s habitat.

There is cause to celebrate small victories for right whales, like the birth of 10 calves this season. But these victories often come hand-in-hand with heartbreak: in June, one of those calves was discovered dead of a ship strike off New Jersey.

Overall, researchers are keenly aware that time is not on the whales’ side, as deaths outpace the speed of regulatory action.

“It’s a very slow process, and keeping the public engaged and keeping funding going is tough when you know you’re not going to see results for 20 years,” said Wiley. “That’s not unique to right whales, but we’re living at the moment in time that things either get better or continue to get worse.”

He added: “The fact that our activity is driving them to extinction is something that isn’t acceptable for us as human beings. We’re better than that.”

The status change reflects the fact that fewer than 250 mature individuals probably remain in a population of roughly 400. While grim, scientists and conservationists expressed hope that this move may help speed up protections for these dwindling giants.