WELCOME TO BLACK HISTORY

PAGE 2

CONTINUING THE HIDDEN HISTORY

ARTICLES OF INTEREST

‘A STORY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE’: A HISTORY OF RACIAL SEGREGATION AND SWIMMING

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*COARD: PHILLY'S TIES TO BIRTH OF SLAVERY 398 YEARS AGO

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*‘DISPLACED & ERASED’: THE UNTOLD STORY OF BLACK CLAYTON, MISSOURI RESIDENTS BEING PUSHED OUT OF THEIR COMMUNITY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*UNTOLD U.S. HEROES(ARTICLE BELOW)

*FROM 15 MILLION ACRES TO 1 MILLION: HOW BLACK PEOPLE LOST THEIR LAND?

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE UNTOLD STORY OF MEMORIAL DAY: FORMER SLAVES HONORING AND MOURNING THE DEAD

THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY OF THE FEDERAL HOLIDAY HAS BEEN NEARLY WIPED FROM PUBLIC MEMORY. (ARTICLE BELOW)

*THEY FOUGHT AND DIED FOR FREEDOM: BLACK SOLDIERS IN THE U.S. CIVIL WAR

( ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE UNTOLD STORY OF MEMORIAL DAY: FORMER SLAVES HONORING AND MOURNING THE DEAD (ARTICLE BELOW)

**THE EASTER SUNDAY MASSACRE IN COLFAX, LOUISIANA, AND THE AWFUL SUPREME COURT DECISION THAT FOLLOWED(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE ROLE OF SLAVERY AND THE SLAVE TRADE IN BUILDING NORTHERN WEALTH(EXCERPT BELOW)

*HOW THE SLAVE TRADE HELPED FINANCE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*DEVIL’S PUNCHBOWL — AN AMERICAN CONCENTRATION CAMP SO HORRIFIC IT WAS ERASED FROM HISTORY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*185TH ANNIVERSARY OF NAT TURNER'S REBELLION(ARTICLE BELOW)

*PAUL ROBESON, A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*SLAVES: THE CAPITAL THAT MADE CAPITALISM(ARTICLE BELOW)

*"THE MEANING OF JULY FOURTH FOR THE NEGRO"(ARTICLE BELOW)

6 Startling Things About Sex Farms During Slavery That You May Not Know

By Curtis Bunn - atlanta black star

‘A story of social justice’: a history of racial segregation and swimming

A new exhibition highlights a shameful history of racism in pools but also a recognition of Black swimming heroes

Lisa Wong Macabasco - the guardian

Wed 23 Mar 2022 01.28 EDT

Aquatic-safety advocate Angela Beale-Tawfeeq grew up swimming at the public pool in her predominantly Black neighborhood. “We always say, ‘In North Philadelphia, born and raised, in the swimming pool is where we spent most of our days,’ she recites, referencing the familiar lyrics of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air theme song.

Now the education and research director of Diversity in Aquatics (one of the nation’s only organizations of Black and brown aquatics professionals), Beale-Tawfeeq is one of the many compelling voices contributing to Pool: A Social History of Segregation, a new wide-ranging exhibition about the United States’s history of segregated swimming and its connection to today’s alarming drowning rates in Black communities. Encompassing history, artworks and storytelling across a broad array of media, the immersive presentation uses public swimming pools as a lens through which to ponder social justice and public health.

The 4,700-sq-ft exhibition is now on view at Philadelphia’s historic Fairmount Water Works, a neo-classical landmark abutting the Schuylkill River that pumped water into the city until the turn of the 20th century and later became an aquarium and then one of the city’s first integrated pools, backed by the father of the actor Grace Kelly. After decades of preservation efforts, most of the building reopened in 2003 as an environmental education center, but the three-lane cement pool area was never restored due to lack of funding, according to Victoria Prizzia, the exhibition organizer.

“It felt very important to have that sacred space – a historic site and former public pool that had been neglected and captured in a state of arrested decay,” says Prizzia, a former lifeguard and competitive swimmer who since 2009 has directed many projects about water issues and the environment. “When you step inside, you really are transported. This is a reclaiming of that space, to tell the story in a different way.”

The exhibition’s projections bring the walls of the space to life. Near the entrance lies a digital pool of water that visitors are encouraged to sit around and virtually dip their feet into while listening to interview excerpts from athletes, activists and academics. “I love when you have the architectural elements speak for themselves, and in this case they really become another character,” Prizzia notes. (And this character has seen its share of floods due to its riverbank location: the exhibition was all set to open in September, but Hurricane Ida swept through mere hours after the opening reception; the space flooded, but miraculously nothing was damaged.)

Public pools have long been contested sites that reflect America’s racial and economic divisions, since the 1920s when pools began to be segregated by race instead of, as previously, by sex or class. A deep anxiety emerged around that time about people of different races and sexes sharing such intimate spaces. In the south, segregation was mandated through city ordinances and other official exclusionary rules; in northern states, de facto segregation occurred as a result of building public pools in white neighborhoods or, more frequently, through intimidation, harassment and violence.

A digital animation commission by the noted Philadelphia playwright James Ijames titled Moving Portraits interweaves the history of segregated swimming with the achievements of Black swimming heroes. Cast on to the Water Works’ historic facade opposite custom stadium seating evoking the golden era of public pools, it’s a highlight of the exhibition, according to Prizzia: “We’re not only showing tragedy but also revealing this other current – the accomplishments that have been forgotten, happening in parallel, by Black swimmers.”

Also largely overlooked is the fact that many non-European peoples were proficient swimmers until the late 1800s, at which point a nascent white beach and pool culture drove people of color away from those spaces. In Pool, this essential and little-known historical context comes via archival images and narratives from Kevin Dawson, author of the 2018 book Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora. “The exhibit is really important in that it’s helping to encourage Black people to get back into the water,” Dawson tells the Guardian. “Many are seeing swimming as kind of their historical heritage that Jim Crow racism denied them.”

The legacy of that shameful history, compounded by the slashing of funds for public pools, is evident in today’s grim drowning disparities: in Pennsylvania, Black children have a 50% higher rate of accidental drowning than white children. Nationwide, Black youth are almost six times more likely than white children to drown in a swimming pool, and 69% of Black children have little to no swimming ability, compared with 42% of white children. “The story of water is really a story of social justice,” says Prizzia, pointing to inequities in land use, infrastructure and pollution in addition to access to swimming spaces.

Philadelphia has a uniquely rich public pool culture, opening the first outdoor municipal pool in the US in 1883 (which functioned as a public bath for poor and immigrant communities who didn’t have indoor plumbing) and, with more than 70 pools, still boasting the largest number of public pools per resident of any large American city. In response to an outcry over drownings in nearby rivers and creeks, seven swim clubs cropped up around the middle of the century to serve both urban and suburban Black swimmers. (Several are still going strong today, including the nation’s first Black-owned swim club.) “Philadelphians love their pools,” Prizzia says. “They’re really important to the fabric of local neighborhoods. They’re like your extended family.”

Beale-Tawfeeq knows that well: “I grew up understanding that learning to swim can actually save lives in more ways than one.” She joined the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation diving team at age 10, later was coached by the visionary Jim Ellis (who formed the country’s first Black swim team and was the subject of the 2007 film Pride), and eventually attended Howard University on an athletic scholarship. Now a physical-education educator, she touts swimming’s health benefits: “It’s a physical activity you can do from six months old until you’re 100.”

Beale-Tawfeeq notes there’s trauma in the exhibition’s narratives, but an exuberant mural at the exhibition entrance hopes to balance that. Created by El Salvador– born, Philadelphia-based artist Calo Rosa and representing an offering to a Yoruba water goddess, the piece exhorts visitors to “dive in”. “We wanted to create an invitation to come in and enjoy too,” Prizzia says. “By excluding people from swimming, you’re also excluding them from a very natural joy. People gravitate toward water; everyone wants to play in it. Hopefully the exhibition is a pathway for people to learn to swim and have access to something that would bring them joy.”

Now the education and research director of Diversity in Aquatics (one of the nation’s only organizations of Black and brown aquatics professionals), Beale-Tawfeeq is one of the many compelling voices contributing to Pool: A Social History of Segregation, a new wide-ranging exhibition about the United States’s history of segregated swimming and its connection to today’s alarming drowning rates in Black communities. Encompassing history, artworks and storytelling across a broad array of media, the immersive presentation uses public swimming pools as a lens through which to ponder social justice and public health.

The 4,700-sq-ft exhibition is now on view at Philadelphia’s historic Fairmount Water Works, a neo-classical landmark abutting the Schuylkill River that pumped water into the city until the turn of the 20th century and later became an aquarium and then one of the city’s first integrated pools, backed by the father of the actor Grace Kelly. After decades of preservation efforts, most of the building reopened in 2003 as an environmental education center, but the three-lane cement pool area was never restored due to lack of funding, according to Victoria Prizzia, the exhibition organizer.

“It felt very important to have that sacred space – a historic site and former public pool that had been neglected and captured in a state of arrested decay,” says Prizzia, a former lifeguard and competitive swimmer who since 2009 has directed many projects about water issues and the environment. “When you step inside, you really are transported. This is a reclaiming of that space, to tell the story in a different way.”

The exhibition’s projections bring the walls of the space to life. Near the entrance lies a digital pool of water that visitors are encouraged to sit around and virtually dip their feet into while listening to interview excerpts from athletes, activists and academics. “I love when you have the architectural elements speak for themselves, and in this case they really become another character,” Prizzia notes. (And this character has seen its share of floods due to its riverbank location: the exhibition was all set to open in September, but Hurricane Ida swept through mere hours after the opening reception; the space flooded, but miraculously nothing was damaged.)

Public pools have long been contested sites that reflect America’s racial and economic divisions, since the 1920s when pools began to be segregated by race instead of, as previously, by sex or class. A deep anxiety emerged around that time about people of different races and sexes sharing such intimate spaces. In the south, segregation was mandated through city ordinances and other official exclusionary rules; in northern states, de facto segregation occurred as a result of building public pools in white neighborhoods or, more frequently, through intimidation, harassment and violence.

A digital animation commission by the noted Philadelphia playwright James Ijames titled Moving Portraits interweaves the history of segregated swimming with the achievements of Black swimming heroes. Cast on to the Water Works’ historic facade opposite custom stadium seating evoking the golden era of public pools, it’s a highlight of the exhibition, according to Prizzia: “We’re not only showing tragedy but also revealing this other current – the accomplishments that have been forgotten, happening in parallel, by Black swimmers.”

Also largely overlooked is the fact that many non-European peoples were proficient swimmers until the late 1800s, at which point a nascent white beach and pool culture drove people of color away from those spaces. In Pool, this essential and little-known historical context comes via archival images and narratives from Kevin Dawson, author of the 2018 book Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora. “The exhibit is really important in that it’s helping to encourage Black people to get back into the water,” Dawson tells the Guardian. “Many are seeing swimming as kind of their historical heritage that Jim Crow racism denied them.”

The legacy of that shameful history, compounded by the slashing of funds for public pools, is evident in today’s grim drowning disparities: in Pennsylvania, Black children have a 50% higher rate of accidental drowning than white children. Nationwide, Black youth are almost six times more likely than white children to drown in a swimming pool, and 69% of Black children have little to no swimming ability, compared with 42% of white children. “The story of water is really a story of social justice,” says Prizzia, pointing to inequities in land use, infrastructure and pollution in addition to access to swimming spaces.

Philadelphia has a uniquely rich public pool culture, opening the first outdoor municipal pool in the US in 1883 (which functioned as a public bath for poor and immigrant communities who didn’t have indoor plumbing) and, with more than 70 pools, still boasting the largest number of public pools per resident of any large American city. In response to an outcry over drownings in nearby rivers and creeks, seven swim clubs cropped up around the middle of the century to serve both urban and suburban Black swimmers. (Several are still going strong today, including the nation’s first Black-owned swim club.) “Philadelphians love their pools,” Prizzia says. “They’re really important to the fabric of local neighborhoods. They’re like your extended family.”

Beale-Tawfeeq knows that well: “I grew up understanding that learning to swim can actually save lives in more ways than one.” She joined the Philadelphia Parks and Recreation diving team at age 10, later was coached by the visionary Jim Ellis (who formed the country’s first Black swim team and was the subject of the 2007 film Pride), and eventually attended Howard University on an athletic scholarship. Now a physical-education educator, she touts swimming’s health benefits: “It’s a physical activity you can do from six months old until you’re 100.”

Beale-Tawfeeq notes there’s trauma in the exhibition’s narratives, but an exuberant mural at the exhibition entrance hopes to balance that. Created by El Salvador– born, Philadelphia-based artist Calo Rosa and representing an offering to a Yoruba water goddess, the piece exhorts visitors to “dive in”. “We wanted to create an invitation to come in and enjoy too,” Prizzia says. “By excluding people from swimming, you’re also excluding them from a very natural joy. People gravitate toward water; everyone wants to play in it. Hopefully the exhibition is a pathway for people to learn to swim and have access to something that would bring them joy.”

Coard: Philly's ties to birth of slavery 398 years ago

Michael Coard

From Philly Tribune: On Aug. 20, it will be exactly 398 years ago to the day that slavery in this country was birthed — actually spawned like a demonic creature — by European/British devilment in 1619. And that racist devil lived throughout America, including here in the so-called City of Brotherly Love.

Before exposing the history of slavery and this city’s ties to it, I gotta give a big shoutout to former FLOTUS, Michelle Obama, Esquire, for telling the truth and literally shaming the “devils” last year in Philly during her powerful sermon at the Democratic National Convention, when she said “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.” Despite the racist news commentators who said she didn’t know what she was talking about, she, being the scholarly Ivy League-educated lawyer that she is, knew exactly what she was talking about. Even the pre-eminent White House Association, a private educational organization founded in 1961, disclosed that the federal government used “African-Americans — both enslaved and free — to provide the bulk of labor that built the White House.” Moreover, the association pointed out that enslaved Blacks also built the “United States Capitol (1793-1800) and other early government buildings.” Now let’s get back to slavery’s origins in this country.

On that fateful Aug. 20, 1619, date as noted by English settler John Rolfe, a rich tobacco planter, “… there came a Dutch man of warre that sold us twenty and odd Negars” in the Virginia Colony at Old Point Comfort (now Fort Comfort in Hampton), making them the first enslaved Blacks on this land. Following raids in southern Africa by Luis Mendes de Vasconcellos and his Portuguese troops beginning in 1617, he invaded the village of Ndongo in Luanda, Angola two years later and loaded 60 of those Kimbundu-speaking human beings aboard the slave ship Sao Joao Bautista before ordering it sent to Vera Cruz, Mexico. After setting sail, that ship encountered an English privateer called the Treasurer, which was accompanied by its enforcer, the White Lion, a ferociously armed Dutch war vessel. Together, they later encountered the Sao Joao Bautista in the waters of the West Indies, attacked it, and robbed it of its entire cargo, including the Africans. Twenty of those 60 were loaded onto the White Lion, which arrived at Old Point Comfort on Aug. 20. The Treasurer arrived a few days later and its captain attempted to trade the remaining 40 but couldn’t get the value he wanted, so he transported them to Bermuda where they, too, were held in brutal bondage.

Among the 20 captured Angolans left at Old Point Comfort, two, namely Antonio and Isabella (whose Spanish Christian names were forced upon them like we name our pets today), were traded to Captain William Tucker for “badly needed provisions.” By the way, four years later, Antonio and Isabella became the parents of the first Black child whose birth was officially documented in Colonial America. And the name imposed upon him was William Tucker — the very same name of the very same captain who enslaved his parents. A third identified person, who was given the name Pedro, and the remaining 17 others were traded for additional products to Governor George Yeardley and his Cape Merchant Abraham Piersey who forced them to labor at plantations along the nearby James River in what would become Charles City.

But such trading, selling and forced labor were not unique to Charles City or James River plantations or Old Point Comfort or Virginia or even the South. They happened right here in Philly, too. On the southwest corner of Front and High — now Market — Street stood the London Coffee House, which opened in 1754 with funds provided by 200 local merchants. It was where shippers, businessmen and local officials, including the governor, socialized, drank coffee and alcohol, and ate in private booths while making deals. It was where, on the High Street side, auctions were held for carriages, foodstuffs and horses — and, by the way, human beings, specifically African humans beings who had just been unloaded from ships that docked right across the street at the Delaware River.

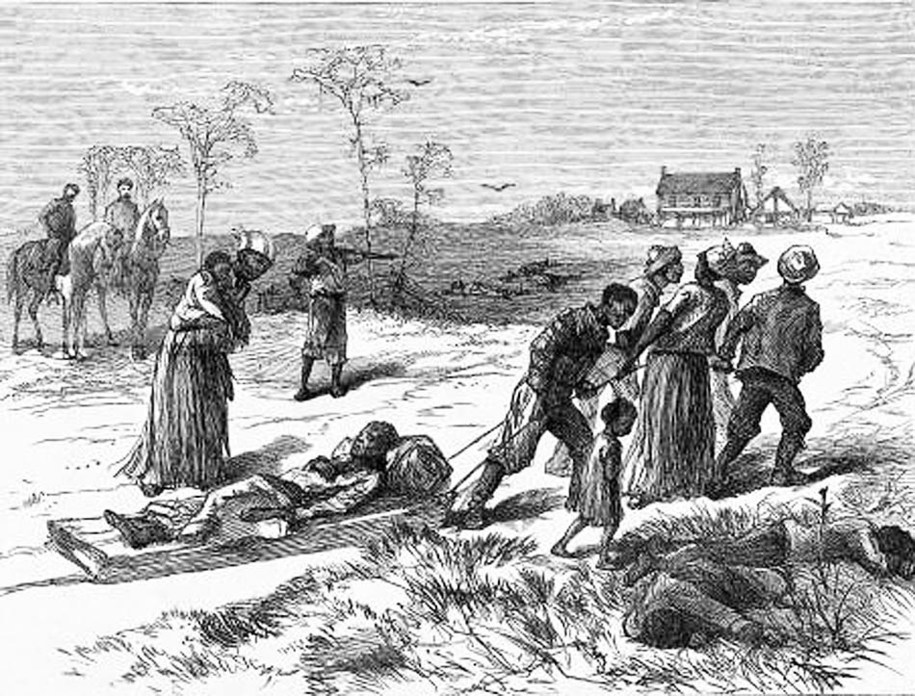

In 1991, a historical marker was installed on the corner of Front and Market streets which reads: “Scene of political and commercial activity in the colonial period, the London Coffee House … served as a place to inspect Black ‘slaves’ recently arrived from Africa and to bid for their purchase at public auctions.” The biddings happened like this: The captured Black men, women and children, usually about five or six at a time, were placed on a thick wooden board that was approximately three feet wide and eight feet long and that was set atop two heavy barrels on each end. These whipped and shackled human beings were paraded onto the boards, displayed by being forced to slowly turn around and bend over, inspected by having their mouths forced open, their genitals grabbed, their limbs and muscles flexed, and then they were auctioned to the highest bidder. Immediately afterward, they were sold off — mother from daughter, father from son, brother from sister, husband from wife. Following these forced separations, they were scattered across the country. And they would never touch or even see one another again.

Slavery was a key component of daily life in Pennsylvania generally and Philadelphia particularly. In the 1760s, nearly 4,500 enslaved Blacks labored in the colony. About one of every six white households in the city held at least one Black person in bondage. This cruel institution began here in 1684 when the slave ship Isabella from Bristol, England, anchored in Philadelphia with 150 captured Africans. A year later, William Penn himself held three Black persons in bondage at his Pennsbury manor, 20 miles north of Philly. Even George Washington enslaved Blacks; 316 to be exact. And he held nine of them right here in the so-called City of Brotherly Love at America’s first “White House,” which was known as the President’s House at Sixth and Market (then High) streets.

Remember Aug. 20, 1619, even after 398 years! In fact, never forget and always avenge. And you can do that by attending a memorial event sponsored by Avenging The Ancestors Coalition (ATAC) on Sunday, Aug. 20 at 3 p.m. at the Slavery Memorial/President’s House at Sixth and Market streets. For more info, call 215-552-8751.

The spirit often moves me to end my weekly columns, whenever appropriate, with a particular inspirational quote from one of the greatest rappers in hip-hop history. In his song entitled “1-9-9-9,” Common said and I’m now saying, “Check it. It’s like I’m fightin’ for freedom, writin’ for freedom. ... My ancestors, when I’m writin’ I see ‘em and talk with ‘em. Hoping in the promised land I can walk with ‘em.”

Before exposing the history of slavery and this city’s ties to it, I gotta give a big shoutout to former FLOTUS, Michelle Obama, Esquire, for telling the truth and literally shaming the “devils” last year in Philly during her powerful sermon at the Democratic National Convention, when she said “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.” Despite the racist news commentators who said she didn’t know what she was talking about, she, being the scholarly Ivy League-educated lawyer that she is, knew exactly what she was talking about. Even the pre-eminent White House Association, a private educational organization founded in 1961, disclosed that the federal government used “African-Americans — both enslaved and free — to provide the bulk of labor that built the White House.” Moreover, the association pointed out that enslaved Blacks also built the “United States Capitol (1793-1800) and other early government buildings.” Now let’s get back to slavery’s origins in this country.

On that fateful Aug. 20, 1619, date as noted by English settler John Rolfe, a rich tobacco planter, “… there came a Dutch man of warre that sold us twenty and odd Negars” in the Virginia Colony at Old Point Comfort (now Fort Comfort in Hampton), making them the first enslaved Blacks on this land. Following raids in southern Africa by Luis Mendes de Vasconcellos and his Portuguese troops beginning in 1617, he invaded the village of Ndongo in Luanda, Angola two years later and loaded 60 of those Kimbundu-speaking human beings aboard the slave ship Sao Joao Bautista before ordering it sent to Vera Cruz, Mexico. After setting sail, that ship encountered an English privateer called the Treasurer, which was accompanied by its enforcer, the White Lion, a ferociously armed Dutch war vessel. Together, they later encountered the Sao Joao Bautista in the waters of the West Indies, attacked it, and robbed it of its entire cargo, including the Africans. Twenty of those 60 were loaded onto the White Lion, which arrived at Old Point Comfort on Aug. 20. The Treasurer arrived a few days later and its captain attempted to trade the remaining 40 but couldn’t get the value he wanted, so he transported them to Bermuda where they, too, were held in brutal bondage.

Among the 20 captured Angolans left at Old Point Comfort, two, namely Antonio and Isabella (whose Spanish Christian names were forced upon them like we name our pets today), were traded to Captain William Tucker for “badly needed provisions.” By the way, four years later, Antonio and Isabella became the parents of the first Black child whose birth was officially documented in Colonial America. And the name imposed upon him was William Tucker — the very same name of the very same captain who enslaved his parents. A third identified person, who was given the name Pedro, and the remaining 17 others were traded for additional products to Governor George Yeardley and his Cape Merchant Abraham Piersey who forced them to labor at plantations along the nearby James River in what would become Charles City.

But such trading, selling and forced labor were not unique to Charles City or James River plantations or Old Point Comfort or Virginia or even the South. They happened right here in Philly, too. On the southwest corner of Front and High — now Market — Street stood the London Coffee House, which opened in 1754 with funds provided by 200 local merchants. It was where shippers, businessmen and local officials, including the governor, socialized, drank coffee and alcohol, and ate in private booths while making deals. It was where, on the High Street side, auctions were held for carriages, foodstuffs and horses — and, by the way, human beings, specifically African humans beings who had just been unloaded from ships that docked right across the street at the Delaware River.

In 1991, a historical marker was installed on the corner of Front and Market streets which reads: “Scene of political and commercial activity in the colonial period, the London Coffee House … served as a place to inspect Black ‘slaves’ recently arrived from Africa and to bid for their purchase at public auctions.” The biddings happened like this: The captured Black men, women and children, usually about five or six at a time, were placed on a thick wooden board that was approximately three feet wide and eight feet long and that was set atop two heavy barrels on each end. These whipped and shackled human beings were paraded onto the boards, displayed by being forced to slowly turn around and bend over, inspected by having their mouths forced open, their genitals grabbed, their limbs and muscles flexed, and then they were auctioned to the highest bidder. Immediately afterward, they were sold off — mother from daughter, father from son, brother from sister, husband from wife. Following these forced separations, they were scattered across the country. And they would never touch or even see one another again.

Slavery was a key component of daily life in Pennsylvania generally and Philadelphia particularly. In the 1760s, nearly 4,500 enslaved Blacks labored in the colony. About one of every six white households in the city held at least one Black person in bondage. This cruel institution began here in 1684 when the slave ship Isabella from Bristol, England, anchored in Philadelphia with 150 captured Africans. A year later, William Penn himself held three Black persons in bondage at his Pennsbury manor, 20 miles north of Philly. Even George Washington enslaved Blacks; 316 to be exact. And he held nine of them right here in the so-called City of Brotherly Love at America’s first “White House,” which was known as the President’s House at Sixth and Market (then High) streets.

Remember Aug. 20, 1619, even after 398 years! In fact, never forget and always avenge. And you can do that by attending a memorial event sponsored by Avenging The Ancestors Coalition (ATAC) on Sunday, Aug. 20 at 3 p.m. at the Slavery Memorial/President’s House at Sixth and Market streets. For more info, call 215-552-8751.

The spirit often moves me to end my weekly columns, whenever appropriate, with a particular inspirational quote from one of the greatest rappers in hip-hop history. In his song entitled “1-9-9-9,” Common said and I’m now saying, “Check it. It’s like I’m fightin’ for freedom, writin’ for freedom. ... My ancestors, when I’m writin’ I see ‘em and talk with ‘em. Hoping in the promised land I can walk with ‘em.”

‘Displaced & Erased’: The Untold Story of Black Clayton, Missouri Residents Being Pushed Out of Their Community

By Gus T. Renegade - August 1, 2017

From Atlanta Black Star: Sounding as if she were describing a mafia hit, Donna Rogers-Beard said Clayton, Missouri’s Black “community was slowly suffocated and then finally snuffed out.” Rogers-Beard, a retired Clayton educator, and other Clayton citizens describe this mid-20th century expulsion in the new documentary film “Displaced & Erased.” Filmmaker Emma Riley exhibits how hundreds of Black residents, many of them homeowners, were methodically ejected from the region beginning in the 1950s. Urban renewal (infamously rebranded “Negro removal”) campaigns nonviolently compelled Black residents to leave and compensated them with market value for their property. City planners plotted an agenda for a prosperous new town, that, according to recent census data, has fewer than 10 percent Black citizens today. Rogers-Beard and scores of former residents described tremendous anguish about being forced to abandon prime property. Nestled minutes beyond the St. Louis city limits, Clayton is now a plush, commercial, nearly all-white enclave.

The eviction of Clayton’s Black inhabitants is part of a pattern in American history of repeated instances of often violent mass expulsions of Black people. The evictions and killings are censored from history, and the Clayton removal is only a more recent illustration of Blacks being wiped off a land.

Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Elliot Jaspin devotes a book to the history of racial cleansings but was forced to limit his work to a dozen of the “worst of the worst” incidents. In “Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America,” Jaspin concludes there were more than 260 incidents where whites violently forced all Black people to flee an entire county. Jaspin’s tally omits nonviolent or small-town removals like Clayton, although he concedes hundreds of these “lesser” cleansings occurred.

A linchpin of Jaspin’s book and the Clayton documentary is white lies. Riley describes this deception as “deliberately leaving information out.” Years after locales like Clayton, Mo., and Forsyth County, Ga., (one of the “worst of the worst” racial cleansings in “Bitter Waters”) were melanin-free, Jaspin submits, “The white community would construct a lie.” As opposed to acknowledging that grandma and grandpa were racist goons who criminally ejected, or killed, legions of Black people, many white descendants offer bogus histories about voluntary, cordial departures of Black residents. Jaspin believes the lies absolve whites of guilt for the ransacking of Black people and further obscure Black property claims and legitimate requests for restitution.

In 2006, the Wilmington Race Riot Commission published findings to offset more than a century of constructed lies about the November 1898 purge of Wilmington, North Carolina. The New York Times provides a tidy summation of their findings: “Scores of black citizens were killed during the uprising — no one yet knows how many — and prominent Blacks and whites were banished from the city under threat of death.”

Filmmaker Christopher Everett, a North Carolina native and creator of the documentary “Wilmington on Fire,” believes the untold number of Black casualties could top a thousand. Highlighting that Wilmington was a majority-Black town at the time of the massacre, Everett cites census data showing Wilmington lost half its Black population in the year following the “cleansing.”

“You had thousands of people that were exiled, but the population change was too drastic for just a hundred or a couple hundred people to get killed,” says Everett.

Texas native E.R. Bills was inspired to investigate the 1910 slaughter and expulsion of Black citizens from Slocum, Texas because of the dubiously low numbers of casualties reported. The conservative estimates of two dozen fatalities or fewer strongly clashed with his extensive research, which includes testimony from the white sheriff at the time of the massacre. Bills says the lawman reported, “There are Black bodies everywhere. Mobs of white people went around killing as many Black people as they could find and run down.” The sheriff’s record and corresponding mass grave sites compelled Bills to conclude the number of Black casualties could easily exceed two hundred.

While writing “The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas,” Bills worked with Constance Hollie-Jawaid, whose great-grandfather was a Slocum business owner and a victim of the massacre and expulsion. While advocating for a historical marker recognizing the assault on Black Texans, Hollie-Jawaid said that some whites thought her ancestor was “uppity,” and used the purge to return him to “his place.”

“They spread rumors and lies, and killed members of my family. Shot and wounded members of my family. And took the granary, the mercantile store, and seven hundred acres of prime fertile land in east Texas. And Texas still refuses to give it back,” said Hollie-Jawaid.

Jaspin reminds us that these expulsions happened more than 260 times.

When describing the long-term economic violence of the Clayton eviction, Emma Riley told St. Louis Public Radio, “This has greater implications for how wealth is transferred from generation to generation because these weren’t just Black people who were renting. They were property owners.”

Underscoring the pattern, John Hopkins University historian N.D.B. Connolly notes similar financial plunder in the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma slaughter, where approximately 300 people died according to the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot Commission. In addition to the bloodletting, Connolly says whites “burned whatever proof existed about the land owners.”

Connolly adds that the confiscation of Black land undergoes upgrades. What was smash and loot in 1898 Wilmington, becomes “eminent domain” and “urban renewal” in 1950 Clayton. But the result is the same. “Negro (wealth) removal.”

“Displaced and Erased” was screened at the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase near the three-year anniversary of the shooting death of Ferguson’s Michael Brown Jr. This year is also the centennial anniversary of the 1917 East St. Louis “race riots,” where the number of casualties remains unknown. All three tragedies reflect the unending racist violence targeting individual, collective, and generational Black well-being. (video)

The eviction of Clayton’s Black inhabitants is part of a pattern in American history of repeated instances of often violent mass expulsions of Black people. The evictions and killings are censored from history, and the Clayton removal is only a more recent illustration of Blacks being wiped off a land.

Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Elliot Jaspin devotes a book to the history of racial cleansings but was forced to limit his work to a dozen of the “worst of the worst” incidents. In “Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America,” Jaspin concludes there were more than 260 incidents where whites violently forced all Black people to flee an entire county. Jaspin’s tally omits nonviolent or small-town removals like Clayton, although he concedes hundreds of these “lesser” cleansings occurred.

A linchpin of Jaspin’s book and the Clayton documentary is white lies. Riley describes this deception as “deliberately leaving information out.” Years after locales like Clayton, Mo., and Forsyth County, Ga., (one of the “worst of the worst” racial cleansings in “Bitter Waters”) were melanin-free, Jaspin submits, “The white community would construct a lie.” As opposed to acknowledging that grandma and grandpa were racist goons who criminally ejected, or killed, legions of Black people, many white descendants offer bogus histories about voluntary, cordial departures of Black residents. Jaspin believes the lies absolve whites of guilt for the ransacking of Black people and further obscure Black property claims and legitimate requests for restitution.

In 2006, the Wilmington Race Riot Commission published findings to offset more than a century of constructed lies about the November 1898 purge of Wilmington, North Carolina. The New York Times provides a tidy summation of their findings: “Scores of black citizens were killed during the uprising — no one yet knows how many — and prominent Blacks and whites were banished from the city under threat of death.”

Filmmaker Christopher Everett, a North Carolina native and creator of the documentary “Wilmington on Fire,” believes the untold number of Black casualties could top a thousand. Highlighting that Wilmington was a majority-Black town at the time of the massacre, Everett cites census data showing Wilmington lost half its Black population in the year following the “cleansing.”

“You had thousands of people that were exiled, but the population change was too drastic for just a hundred or a couple hundred people to get killed,” says Everett.

Texas native E.R. Bills was inspired to investigate the 1910 slaughter and expulsion of Black citizens from Slocum, Texas because of the dubiously low numbers of casualties reported. The conservative estimates of two dozen fatalities or fewer strongly clashed with his extensive research, which includes testimony from the white sheriff at the time of the massacre. Bills says the lawman reported, “There are Black bodies everywhere. Mobs of white people went around killing as many Black people as they could find and run down.” The sheriff’s record and corresponding mass grave sites compelled Bills to conclude the number of Black casualties could easily exceed two hundred.

While writing “The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas,” Bills worked with Constance Hollie-Jawaid, whose great-grandfather was a Slocum business owner and a victim of the massacre and expulsion. While advocating for a historical marker recognizing the assault on Black Texans, Hollie-Jawaid said that some whites thought her ancestor was “uppity,” and used the purge to return him to “his place.”

“They spread rumors and lies, and killed members of my family. Shot and wounded members of my family. And took the granary, the mercantile store, and seven hundred acres of prime fertile land in east Texas. And Texas still refuses to give it back,” said Hollie-Jawaid.

Jaspin reminds us that these expulsions happened more than 260 times.

When describing the long-term economic violence of the Clayton eviction, Emma Riley told St. Louis Public Radio, “This has greater implications for how wealth is transferred from generation to generation because these weren’t just Black people who were renting. They were property owners.”

Underscoring the pattern, John Hopkins University historian N.D.B. Connolly notes similar financial plunder in the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma slaughter, where approximately 300 people died according to the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot Commission. In addition to the bloodletting, Connolly says whites “burned whatever proof existed about the land owners.”

Connolly adds that the confiscation of Black land undergoes upgrades. What was smash and loot in 1898 Wilmington, becomes “eminent domain” and “urban renewal” in 1950 Clayton. But the result is the same. “Negro (wealth) removal.”

“Displaced and Erased” was screened at the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase near the three-year anniversary of the shooting death of Ferguson’s Michael Brown Jr. This year is also the centennial anniversary of the 1917 East St. Louis “race riots,” where the number of casualties remains unknown. All three tragedies reflect the unending racist violence targeting individual, collective, and generational Black well-being. (video)

UNTOLD U.S. HEROES

John N. Mitchell Tribune Staff Writer

From Philly Tribune: Perhaps no people had tougher decisions to make regarding the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) than did African-Americans, free or enslaved.

At issue was fighting for the 13 colonies, all of which had slavery in some form in 1776, or fighting alongside the Armies of the British Empire.

It is estimated that as many as 5,000 Blacks fought in the Continental Army in some capacity. However, records show that Blacks opting to fight in the Armies of the British Empire numbered anywhere from 10,000 to as high as 30,000 30,000.

“It was an incredibly complex life and death decision for people of African descent to make,” said Phillip Mead, chief historian and director of curatorial affairs at the Museum of the American Revolution.

The museum has committed an entire portion of its exhibit to the complex role of Blacks in the Revolutionary War. Titled “Finding Freedom,” the exhibit focuses primarily on the role Blacks played in the war and the some of the legal battles that were fought for freedom.

Focused mostly on the summer of 1781 in Virginia, which at the time had the largest slave population, both armies were moving through the state and casualties were high.

One story is that of London Pleasants, a 15-year-old slave owned by Quaker Robert Pleasants. Robert Pleasants wanted to free his slaves, and it was written in his father’s will. However, Virginia law did not permit the freeing of slaves.

In 1779, British General Henry Clinton published the Phillipsburg Proclamation, intended to encourage slaves to run away and join the Royal forces. Infamous traitor Benedict Arnold, now a British general, offered London Pleasants his freedom. Pleasants accepted the offer and became a trumpeter in the Royal Army.

London Pleasants’ story is just one of five interactive displays in the exhibit that tells the story of the quest for freedom.

The Phillipsburg Proclamation was the second enticement for slaves to join the Royal Army; Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775, which offered the first large-scale emancipation of slave and servant labor in the history of colonial British America, was the first.

Born a free man in Philadelphia, 15-year-old James Forten loved his life in the colonies, so much so that he joined a maritime service to fight the British. Captured and offered both his freedom and an education in Britain, Forten requested and received a return to the United States.

This worked well for Forten, according to Mead, as Forten “came back here and became quite wealthy and an abolitionist.

“He could have had his freedom in either place but he chose the United States,” Mead said.

The Treaty of Paris, which marked the British surrender in 1783, promised the return of all property, including slaves. However, the British kept their promise of freedom to the runaways, never returning about 3,000 slaves to former masters and instead freeing them to British territories such as Nova Scotia.

Mead said there were probably many other Blacks who helped the Continental Army — mostly from northern states where some Blacks already had their freedom and slavery was far less brutal — than history accounts for. However, he added that it made sense for slaves in places such as Virginia and the Carolinas to join the Royal Army with its promise of freedom.

“It’s tempting to say one side is fighting for freedom and the other isn’t,” he said. “It’s a complicated story. In some ways the British and the U.S. were competing to say they were the land of liberty. It became a big issue for both sides.”

At issue was fighting for the 13 colonies, all of which had slavery in some form in 1776, or fighting alongside the Armies of the British Empire.

It is estimated that as many as 5,000 Blacks fought in the Continental Army in some capacity. However, records show that Blacks opting to fight in the Armies of the British Empire numbered anywhere from 10,000 to as high as 30,000 30,000.

“It was an incredibly complex life and death decision for people of African descent to make,” said Phillip Mead, chief historian and director of curatorial affairs at the Museum of the American Revolution.

The museum has committed an entire portion of its exhibit to the complex role of Blacks in the Revolutionary War. Titled “Finding Freedom,” the exhibit focuses primarily on the role Blacks played in the war and the some of the legal battles that were fought for freedom.

Focused mostly on the summer of 1781 in Virginia, which at the time had the largest slave population, both armies were moving through the state and casualties were high.

One story is that of London Pleasants, a 15-year-old slave owned by Quaker Robert Pleasants. Robert Pleasants wanted to free his slaves, and it was written in his father’s will. However, Virginia law did not permit the freeing of slaves.

In 1779, British General Henry Clinton published the Phillipsburg Proclamation, intended to encourage slaves to run away and join the Royal forces. Infamous traitor Benedict Arnold, now a British general, offered London Pleasants his freedom. Pleasants accepted the offer and became a trumpeter in the Royal Army.

London Pleasants’ story is just one of five interactive displays in the exhibit that tells the story of the quest for freedom.

The Phillipsburg Proclamation was the second enticement for slaves to join the Royal Army; Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775, which offered the first large-scale emancipation of slave and servant labor in the history of colonial British America, was the first.

Born a free man in Philadelphia, 15-year-old James Forten loved his life in the colonies, so much so that he joined a maritime service to fight the British. Captured and offered both his freedom and an education in Britain, Forten requested and received a return to the United States.

This worked well for Forten, according to Mead, as Forten “came back here and became quite wealthy and an abolitionist.

“He could have had his freedom in either place but he chose the United States,” Mead said.

The Treaty of Paris, which marked the British surrender in 1783, promised the return of all property, including slaves. However, the British kept their promise of freedom to the runaways, never returning about 3,000 slaves to former masters and instead freeing them to British territories such as Nova Scotia.

Mead said there were probably many other Blacks who helped the Continental Army — mostly from northern states where some Blacks already had their freedom and slavery was far less brutal — than history accounts for. However, he added that it made sense for slaves in places such as Virginia and the Carolinas to join the Royal Army with its promise of freedom.

“It’s tempting to say one side is fighting for freedom and the other isn’t,” he said. “It’s a complicated story. In some ways the British and the U.S. were competing to say they were the land of liberty. It became a big issue for both sides.”

FROM 15 MILLION ACRES TO 1 MILLION: HOW BLACK PEOPLE LOST THEIR LAND?

BY DAVID LOVE - JUNE 30, 2017

From Atlanta Black Star: At its height, Black land ownership was impressive. At the turn of the 20th century, formerly enslaved Black people and their heirs owned 15 million acres of land, primarily in the South, mostly used for farming. In 1920, the 925,000 African-American farms represented 14 percent of the farms in America. Sadly, things turned for the worse, as 600,000 Black farmers were forced off their land, with only 45,000 Black farms remaining in 1975. Now, Black folks are only 1 percent of rural landowners in the U.S., and under 2 percent of farmers. Of the 1 billion acres of arable land in America, Black people today own a little more than 1 million acres, according to AP.

During the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Agriculture settled with Black farmers for $2.3 billion for their longstanding claims of discrimination in farm loans and other government programs.

Over the years, Black people have lost their land through a number of circumstances, including government action, deception and a reign of domestic terror in the South that forced Black people from their homes through threats of violence and lynching. That terror and economic exploitation precipitated the Great Migration, which resulted in the uprooting of over 6 million Black people from the South and their relocation to the North, Midwest and West between 1916 and 1970.

How we lost the land is an untold story. An investigation by AP documented the process by which people were tricked or intimated out of their property. In this study of 107 land takings in 13 Southern and border states, 406 landowners lost over 24,000 acres of farm and timber land and 85 properties such as city lots and stores. The property, which today is owned by white people and corporations, is valued in the tens of millions of dollars. In recent years, groups such as the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in Atlanta and the Land Loss Prevention Project in Durham, N.C., receive new reports of land takings on a regular basis, while the Penn Center in St. Helena Island, S.C., has gathered 2,000 such cases. One story from the AP provides the context by which families lost their land to thievery and violence:

After midnight on Oct. 4, 1908, 50 hooded white men surrounded the home of a black farmer in Hickman, Ky., and ordered him to come out for a whipping. When David Walker refused and shot at them instead, the mob poured coal oil on his house and set it afire, according to contemporary newspaper accounts. Pleading for mercy, Walker ran out the front door, followed by four screaming children and his wife, carrying a baby in her arms. The mob shot them all, wounding three children and killing the others. Walker’s oldest son never escaped the burning house. No one was ever charged with the killings, and the surviving children were deprived of the farm their father died defending. Land records show that Walker’s 2 1/2-acre farm was simply folded into the property of a white neighbor. The neighbor soon sold it to another man, whose daughter owns the undeveloped land today.

Land is among the most important assets people can own. Certainly, for the rural society in which many African Americans traditionally have lived, land represented prosperity, intergenerational wealth, family and community. According to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), land can be “a vital part of cultural and social identities, a valuable asset to stimulate economic growth and a central component to preserving natural resources and building societies that are inclusive, resilient and sustainable.”

“It’s more about land as a home, it’s about economics and culture, all rolled up into one,” Jennie L. Stephens, executive director of the Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation said. Based in Charleston, S.C., the organization serves 15 counties in the Palmetto State, including the Lowcountry, where Gullah-Geechee have struggled to hold onto their ancestral homelands on the Sea Islands in the face of development, gentrification and corporate intrusion. For generations, families have had the land, procured through the blood, sweat and tears of their ancestors, until many are forced to sell it.[...]

(read more)

During the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Agriculture settled with Black farmers for $2.3 billion for their longstanding claims of discrimination in farm loans and other government programs.

Over the years, Black people have lost their land through a number of circumstances, including government action, deception and a reign of domestic terror in the South that forced Black people from their homes through threats of violence and lynching. That terror and economic exploitation precipitated the Great Migration, which resulted in the uprooting of over 6 million Black people from the South and their relocation to the North, Midwest and West between 1916 and 1970.

How we lost the land is an untold story. An investigation by AP documented the process by which people were tricked or intimated out of their property. In this study of 107 land takings in 13 Southern and border states, 406 landowners lost over 24,000 acres of farm and timber land and 85 properties such as city lots and stores. The property, which today is owned by white people and corporations, is valued in the tens of millions of dollars. In recent years, groups such as the Federation of Southern Cooperatives in Atlanta and the Land Loss Prevention Project in Durham, N.C., receive new reports of land takings on a regular basis, while the Penn Center in St. Helena Island, S.C., has gathered 2,000 such cases. One story from the AP provides the context by which families lost their land to thievery and violence:

After midnight on Oct. 4, 1908, 50 hooded white men surrounded the home of a black farmer in Hickman, Ky., and ordered him to come out for a whipping. When David Walker refused and shot at them instead, the mob poured coal oil on his house and set it afire, according to contemporary newspaper accounts. Pleading for mercy, Walker ran out the front door, followed by four screaming children and his wife, carrying a baby in her arms. The mob shot them all, wounding three children and killing the others. Walker’s oldest son never escaped the burning house. No one was ever charged with the killings, and the surviving children were deprived of the farm their father died defending. Land records show that Walker’s 2 1/2-acre farm was simply folded into the property of a white neighbor. The neighbor soon sold it to another man, whose daughter owns the undeveloped land today.

Land is among the most important assets people can own. Certainly, for the rural society in which many African Americans traditionally have lived, land represented prosperity, intergenerational wealth, family and community. According to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), land can be “a vital part of cultural and social identities, a valuable asset to stimulate economic growth and a central component to preserving natural resources and building societies that are inclusive, resilient and sustainable.”

“It’s more about land as a home, it’s about economics and culture, all rolled up into one,” Jennie L. Stephens, executive director of the Center for Heirs’ Property Preservation said. Based in Charleston, S.C., the organization serves 15 counties in the Palmetto State, including the Lowcountry, where Gullah-Geechee have struggled to hold onto their ancestral homelands on the Sea Islands in the face of development, gentrification and corporate intrusion. For generations, families have had the land, procured through the blood, sweat and tears of their ancestors, until many are forced to sell it.[...]

(read more)

The Untold Story of Memorial Day: Former Slaves Honoring and Mourning the Dead

The African-American history of the federal holiday has been nearly wiped from public memory.

By Sarah Lazare / AlterNet May 30, 2016

Union General John Logan is often credited with founding Memorial Day. The commander-in-chief of a Union veterans’ organization called the Grand Army of the Republic, Logan issued a decree establishing what was then named “Decoration Day” on May 5, 1868, declaring it “designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land.”

Today, cities across the North and South claim credit for establishing the first Decoration Day—from Macon, Georgia to Richmond, Virginia to Carbondale, Illinois. Yet, a key story of the holiday has been nearly erased from public memory and most official accounts, including that offered by the the Department of Veterans Affairs.

During the spring of 1865, African-Americans in Charleston, South Carolina—most of them former slaves—held a series of memorials and rituals to honor unnamed fallen Union soldiers and boldly celebrate the struggle against slavery. One of the largest such events took place on May first of that year but had been largely forgotten until David Blight, a history professor at Yale University, found records at a Harvard archive. In a New York Times article published in 2011, Blight described the scene. While it is difficult to pinpoint the precise birthplace of the holiday, it is fair to say that ceremonies like the following are largely erased from the American narrative of Memorial Day.

During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the city’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club into an outdoor prison. Union captives were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand.

After the Confederate evacuation of Charleston black workmen went to the site, reburied the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

The symbolic power of this Low Country planter aristocracy’s bastion was not lost on the freedpeople, who then, in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged a parade of 10,000 on the track. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

The procession was led by 3,000 black schoolchildren carrying armloads of roses and singing the Union marching song “John Brown’s Body.” Several hundred black women followed with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses. Then came black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantrymen. Within the cemetery enclosure a black children’s choir sang “We’ll Rally Around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner” and spirituals before a series of black ministers read from the Bible.

After the dedication the crowd dispersed into the infield and did what many of us do on Memorial Day: enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches and watched soldiers drill. Among the full brigade of Union infantrymen participating were the famous 54th Massachusetts and the 34th and 104th United States Colored Troops, who performed a special double-columned march around the gravesite.

This story of Memorial Day, also reported by Victoria M. Massie of Vox, was not merely excluded from the history books but appears to have been actively suppressed. The park where the race course prison camp once stood was eventually named Hampton Park after the Confederate General Wade Hampton who became South Carolina’s governor following the civil war.

In 1966, former President Lyndon B. Johnson declared Waterloo, New York to be the official birthplace of Memorial Day. Then, in 1971, Congress established “Memorial Day” as an official federal holiday to honor all Americans who have fallen in U.S. Wars. In an article published in 2013 on Snopes.com, writer David Mikkelson used these official declarations, as well as the decree issued by Logan, to bolster his argument that African-Americans in Charleston probably should not be credited for establishing the holiday. He further noted that numerous other towns and cities claim to have created the first ceremonies. Yet, Mikkelson's reasoning fails to account for the systematic and proven appropriation, erasure and distortion of African-American history by presidents, lawmakers, generals and scholars alike. The fact that the role of African-Americans is missing from the official record is precisely the problem. At the very least, the contribution of Black people in Charleston has been erased from the public narrative of Memorial Day and deserves to be recognized.

World War II veteran Howard Zinn argued in 1976 that the holiday has since become an uncritical celebration of war-making. “Memorial Day should be a day for putting flowers on graves and planting trees,” he wrote. “Also, for destroying the weapons of death that endanger us more than they protect us, that waste our resources and threaten our children and grandchildren.”

Yet Memorial Day has other troubling modern-day manifestations. Today, while confederate symbols across the United States are increasingly rejected as racist, civil war reenactors still gather in Charleston for a public ceremony, held shortly after Memorial Day, to honor the confederacy on the anniversary of General Stonewall Jackson’s death in 1863. The ceremony is slated to take place next weekend, even after last summer’s white supremacist massacre at Charleston's Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in nine African-Americans were slaughtered.

Charleston officials have taken some small steps towards recognizing the city's African-American history. Following a community campaign, the city of Charleston finally held its first formal commemoration of the African-American roots of Memorial Day in 2010, and the following year it established a plaque. Yet, the history of former slaves’ efforts to give the union dead a proper burial is missing from the park’s official history, made available online by the Parks Conservancy.

Dot Scott, president of the Charleston branch of the NAACP, told AlterNet, “Many of the issues we have around race are based on the fact that these stories have not been told. It sends the message that the contributions of African-Americans are not valued and respected."

Today, cities across the North and South claim credit for establishing the first Decoration Day—from Macon, Georgia to Richmond, Virginia to Carbondale, Illinois. Yet, a key story of the holiday has been nearly erased from public memory and most official accounts, including that offered by the the Department of Veterans Affairs.

During the spring of 1865, African-Americans in Charleston, South Carolina—most of them former slaves—held a series of memorials and rituals to honor unnamed fallen Union soldiers and boldly celebrate the struggle against slavery. One of the largest such events took place on May first of that year but had been largely forgotten until David Blight, a history professor at Yale University, found records at a Harvard archive. In a New York Times article published in 2011, Blight described the scene. While it is difficult to pinpoint the precise birthplace of the holiday, it is fair to say that ceremonies like the following are largely erased from the American narrative of Memorial Day.

During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the city’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club into an outdoor prison. Union captives were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand.

After the Confederate evacuation of Charleston black workmen went to the site, reburied the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

The symbolic power of this Low Country planter aristocracy’s bastion was not lost on the freedpeople, who then, in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged a parade of 10,000 on the track. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”

The procession was led by 3,000 black schoolchildren carrying armloads of roses and singing the Union marching song “John Brown’s Body.” Several hundred black women followed with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses. Then came black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantrymen. Within the cemetery enclosure a black children’s choir sang “We’ll Rally Around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner” and spirituals before a series of black ministers read from the Bible.

After the dedication the crowd dispersed into the infield and did what many of us do on Memorial Day: enjoyed picnics, listened to speeches and watched soldiers drill. Among the full brigade of Union infantrymen participating were the famous 54th Massachusetts and the 34th and 104th United States Colored Troops, who performed a special double-columned march around the gravesite.

This story of Memorial Day, also reported by Victoria M. Massie of Vox, was not merely excluded from the history books but appears to have been actively suppressed. The park where the race course prison camp once stood was eventually named Hampton Park after the Confederate General Wade Hampton who became South Carolina’s governor following the civil war.

In 1966, former President Lyndon B. Johnson declared Waterloo, New York to be the official birthplace of Memorial Day. Then, in 1971, Congress established “Memorial Day” as an official federal holiday to honor all Americans who have fallen in U.S. Wars. In an article published in 2013 on Snopes.com, writer David Mikkelson used these official declarations, as well as the decree issued by Logan, to bolster his argument that African-Americans in Charleston probably should not be credited for establishing the holiday. He further noted that numerous other towns and cities claim to have created the first ceremonies. Yet, Mikkelson's reasoning fails to account for the systematic and proven appropriation, erasure and distortion of African-American history by presidents, lawmakers, generals and scholars alike. The fact that the role of African-Americans is missing from the official record is precisely the problem. At the very least, the contribution of Black people in Charleston has been erased from the public narrative of Memorial Day and deserves to be recognized.

World War II veteran Howard Zinn argued in 1976 that the holiday has since become an uncritical celebration of war-making. “Memorial Day should be a day for putting flowers on graves and planting trees,” he wrote. “Also, for destroying the weapons of death that endanger us more than they protect us, that waste our resources and threaten our children and grandchildren.”

Yet Memorial Day has other troubling modern-day manifestations. Today, while confederate symbols across the United States are increasingly rejected as racist, civil war reenactors still gather in Charleston for a public ceremony, held shortly after Memorial Day, to honor the confederacy on the anniversary of General Stonewall Jackson’s death in 1863. The ceremony is slated to take place next weekend, even after last summer’s white supremacist massacre at Charleston's Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, in nine African-Americans were slaughtered.

Charleston officials have taken some small steps towards recognizing the city's African-American history. Following a community campaign, the city of Charleston finally held its first formal commemoration of the African-American roots of Memorial Day in 2010, and the following year it established a plaque. Yet, the history of former slaves’ efforts to give the union dead a proper burial is missing from the park’s official history, made available online by the Parks Conservancy.

Dot Scott, president of the Charleston branch of the NAACP, told AlterNet, “Many of the issues we have around race are based on the fact that these stories have not been told. It sends the message that the contributions of African-Americans are not valued and respected."

The Easter Sunday massacre in Colfax, Louisiana, and the awful Supreme Court decision that followed

By Denise Oliver Velez

Sunday Apr 16, 2017 · 6:00 AM PDT

From Daily Kos: When Christians think of the meaning of Easter Sunday, it symbolizes resurrection and hope. When I think of Easter Sunday in the black community, I think of all the ladies in their wonderful hats heading off to church. However, I don’t ever forget that Easter Sunday also marked one of the most horrible massacres of black citizens in U.S. history. It’s hard to erase the images in my mind of black bodies riddled with bullets, blown apart by cannon fire. They died at the hands of white supremacists who lost the Civil War but who won the years ahead, because they were able to destroy Reconstruction. I take a moment of silence and say a prayer for the dead, many of whose names we will never know.

This story from The Root on the Colfax Massacre, written by Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., gives the details. It’s worth reading in its entirety.

In Colfax, La., on Easter Sunday 1873, a mob of white insurgents, including ex-Confederate and Union soldiers, led an assault on the Grant Parish Courthouse, the center of civic life in the community, which was occupied and surrounded — and defended — by black citizens determined to safeguard the results of the state's most recent election. They, too, were armed, but they did not have the ammunition to outlast their foes, who, outflanking them, proceeded to mow down dozens of the courthouse's black defenders, even when they surrendered their weapons. The legal ramifications were as horrifying as the violence — and certainly more enduring; in an altogether different kind of massacre, United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the U.S. Supreme Court tossed prosecutors' charges against the killers in favor of severely limiting the federal government's role in protecting the emancipated from racial targeting, especially at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan.

Historians know this tragedy as the Colfax Massacre, though in the aftermath, even today, some whites refer to it as the Colfax Riot in order to lay blame at the feet of those who, lifeless, could not tell their tale. In his canonical history of the period, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, Eric Foner has called the Colfax Massacre "[t]he bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era."

Listening to the testimony of now Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch (heaven help us all) in which he harped on “judicial precedent” over and over again brought to mind Supreme Court precedents like Dred Scott v. Sanford, Plessy v. Ferguson, and the aforementioned United States v. Cruikshank—all of which have the dubious distinction of residing on lists of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time. ...

...For the detailed story of the massacre and the heinous Supreme Court decision that ensued, read The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, by Charles Lane.

This story from The Root on the Colfax Massacre, written by Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., gives the details. It’s worth reading in its entirety.

In Colfax, La., on Easter Sunday 1873, a mob of white insurgents, including ex-Confederate and Union soldiers, led an assault on the Grant Parish Courthouse, the center of civic life in the community, which was occupied and surrounded — and defended — by black citizens determined to safeguard the results of the state's most recent election. They, too, were armed, but they did not have the ammunition to outlast their foes, who, outflanking them, proceeded to mow down dozens of the courthouse's black defenders, even when they surrendered their weapons. The legal ramifications were as horrifying as the violence — and certainly more enduring; in an altogether different kind of massacre, United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the U.S. Supreme Court tossed prosecutors' charges against the killers in favor of severely limiting the federal government's role in protecting the emancipated from racial targeting, especially at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan.

Historians know this tragedy as the Colfax Massacre, though in the aftermath, even today, some whites refer to it as the Colfax Riot in order to lay blame at the feet of those who, lifeless, could not tell their tale. In his canonical history of the period, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, Eric Foner has called the Colfax Massacre "[t]he bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era."

Listening to the testimony of now Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch (heaven help us all) in which he harped on “judicial precedent” over and over again brought to mind Supreme Court precedents like Dred Scott v. Sanford, Plessy v. Ferguson, and the aforementioned United States v. Cruikshank—all of which have the dubious distinction of residing on lists of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time. ...

...For the detailed story of the massacre and the heinous Supreme Court decision that ensued, read The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction, by Charles Lane.

The role of slavery and the slave trade in building northern wealth

By Denise Oliver Velez

Sunday Feb 12, 2017

From Daily Kos: On my way to work, I drive past a statue and memorial park dedicated to Sojourner Truth in Port Ewan, Esopus, New York. It depicts young Isabella Baumfree, who was enslaved in that village. When I get to the campus where I teach at SUNY New Paltz, I frequently use the resources of the library — which is named after Sojourner Truth and has documented her time here in Ulster County.

I was pleased to see local news coverage recently about her and the park.

Not many people outside Ulster County know where the abolitionist Sojourner Truth is from. In the 1840s and 1850s, she traveled through New England and Western states teaching about the horrors of slavery. Her message will forever live on through history. “Trying to convert the common people to understand that what was happening was not only a crime but a sin,” said former Ulster County Historian Anne Gordon.

Sojourner Truth was born in the town of Esopus and was sold many times in the county. A statue in Esopus shows the brutality she endured as a slave. Trina Greene made the Sojourner Truth Sculpture, which depicts marks from where her master whipped her. “He whipped her because she spoke only Dutch,” said Greene.

She spent much of her life in Ulster County, but it was on a road in West Park where she escaped slavery and found freedom in Rifton. “She decides she’s in control here and she’s going to decide what happens in her life,” said Gordon. That determination took her to Ulster County Court in Kingston where she sued the man who sold her son into slavery. With that act, she became the first black woman to successfully sue a white man in court...

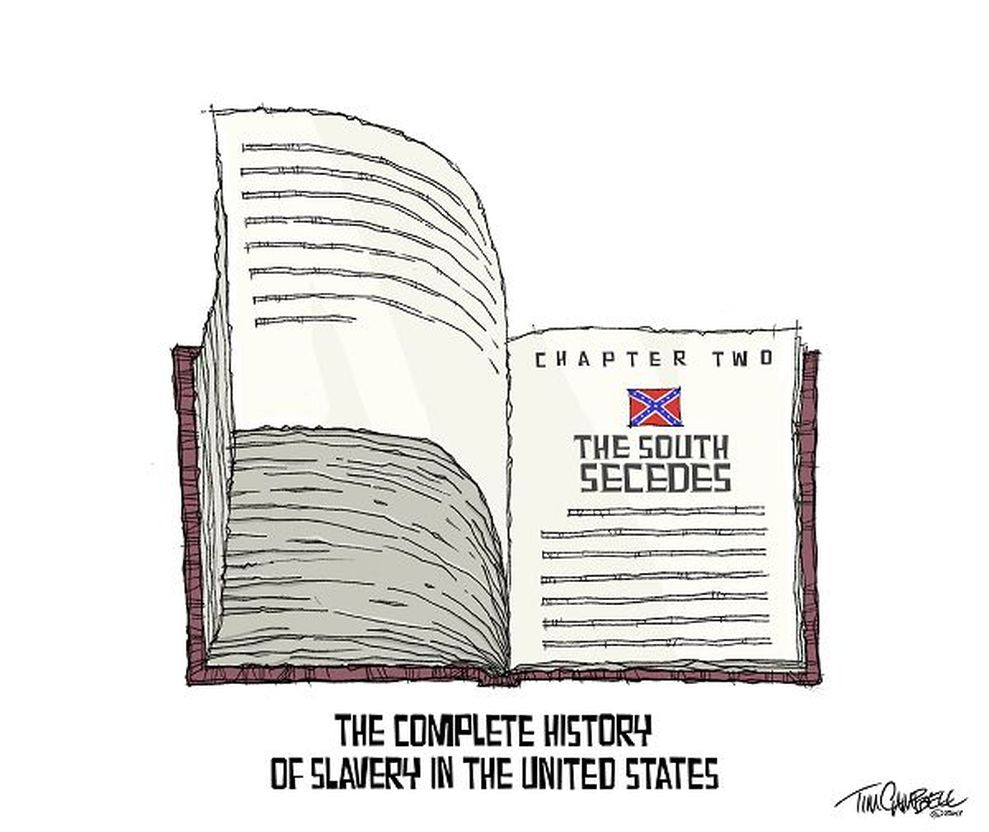

...It never ceases to amaze that even students who use our school library on an everyday basis, when asked for their thoughts about slavery, immediately mention the South and the Civil War. Those who are not bIack see no connection between their present and our past. If they mention the North at all, it is as the destination point for escape from the South via the Underground Railroad. They cite Harriet Tubman or the place from which former slaves waged mighty abolitionist battles, like those spearheaded by Frederick Douglass (don’t get me started on current White House occupant’s ignorance on Douglass). A few mention ancestors who fought in the Civil War—for the Union. This lopsided view of American history colors current day discussions of race and racism with too much finger-pointing only at the South and white southerners. It is rare to hear discourse on northern culpability. This oversight encourages a disassociation with white privilege benefits reaped by northerners who can say, “but … but … my family came here after slavery was over,” or “my ancestors didn’t own slaves.”

Racism is not regional and the enslavement legacy inherited from the time of the founding of our country affects all of us in the U.S., no matter our color, location, or date of immigration...

...Sylvester Manor was not the only enslavement site on Long Island, as detailed in “Confronting Slavery at Long Island’s Oldest Estates.”

New York City’s slave market was second in size only to Charleston’s. Even after the Revolution, New York was the most significant slaveholding state north of the Mason-Dixon line. In 1790, nearly 40 percent of households in the area immediately around New York City owned slaves — a greater percentage than in any Southern state as a whole, according to one study.

In contrast to the image of large gangs working in cotton fields before retiring to a row of cabins, slaveholdings in New York State were small, with the enslaved often living singly or in small groups, working alongside and sleeping in the same houses as their owners. Privacy was scant, and in contrast to any notion of a less severe Northern slavery, the historical record is full of accounts of harsh punishments for misbehavior. “Slavery in the North was different, but I don’t think it was any easier,” Mr. McGill said. “The enslaved were a lot more scrutinized in those places, a lot more restricted. That would have been very tough to endure.”

Slavery in Southampton, the oldest English settlement in New York, dates almost to its founding in the 1640s. A slave and Indian uprising burned many buildings in the 1650s. Census records show that by 1686, roughly 10 percent of the village’s nearly 800 inhabitants were slaves, many of whom helped work the rich agricultural land. But this is not a part of its history that the town, better known for its spectacular beach and staggeringly expensive real estate, has been eager to embrace. “I think for a while a lot of people didn’t know or didn’t want to acknowledge there were slaves out here,” said Brenda Simmons, executive director of the Southampton African-American Museum, which plans to open in an old barbershop — the village’s first designated African-American landmark — on North Sea Road. Mr. McGill’s visit, she said, “will help confirm the truth of the matter.”...

...

The website for the film includes a wealth of instructional materials. One I use frequently is “Myths About Slavery.” Here’s the PDF:

Contrary to popular belief:

I was pleased to see local news coverage recently about her and the park.