Welcome to reality - trivia

Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today.

Malcolm X

july 2024

TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

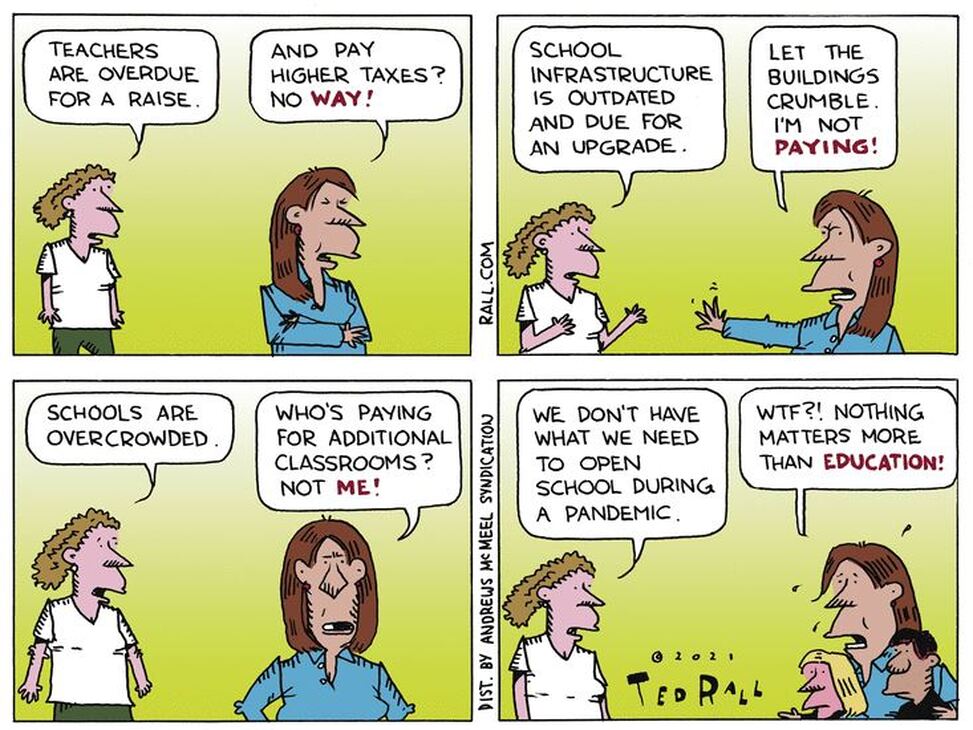

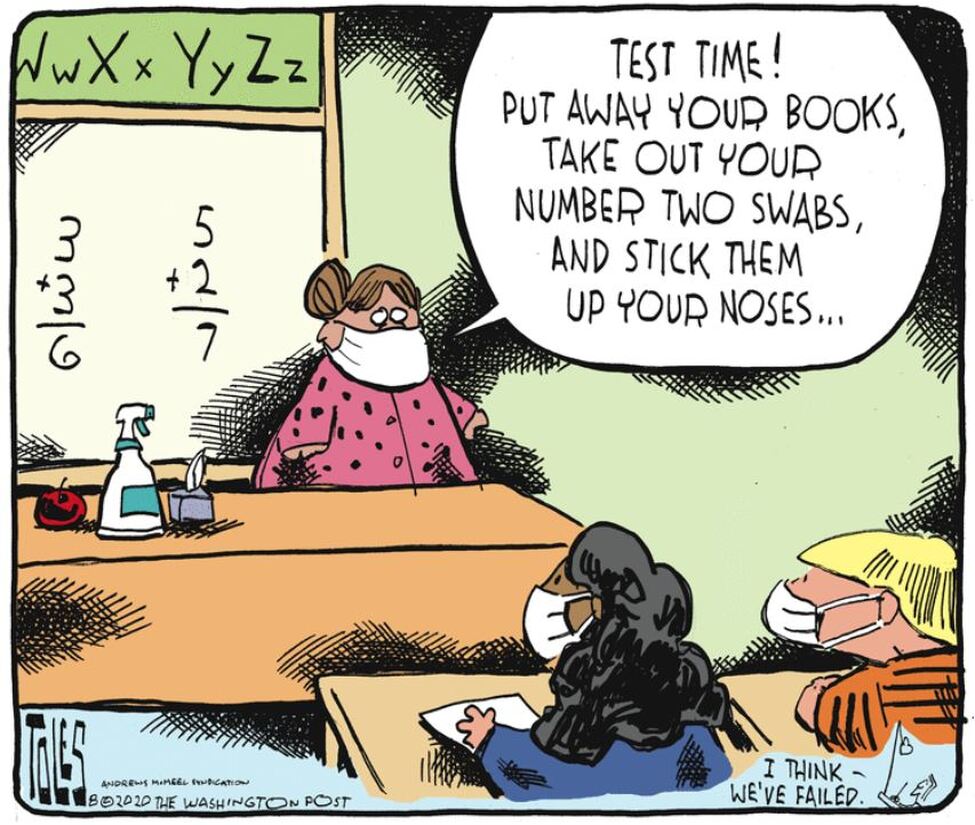

teaching in america

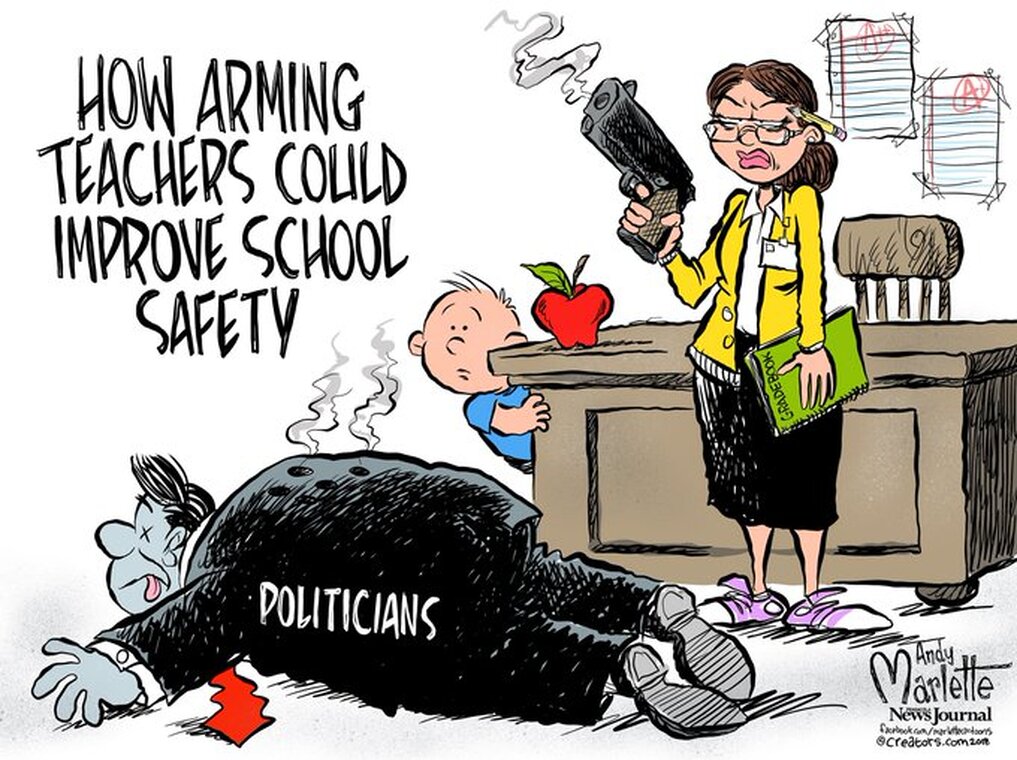

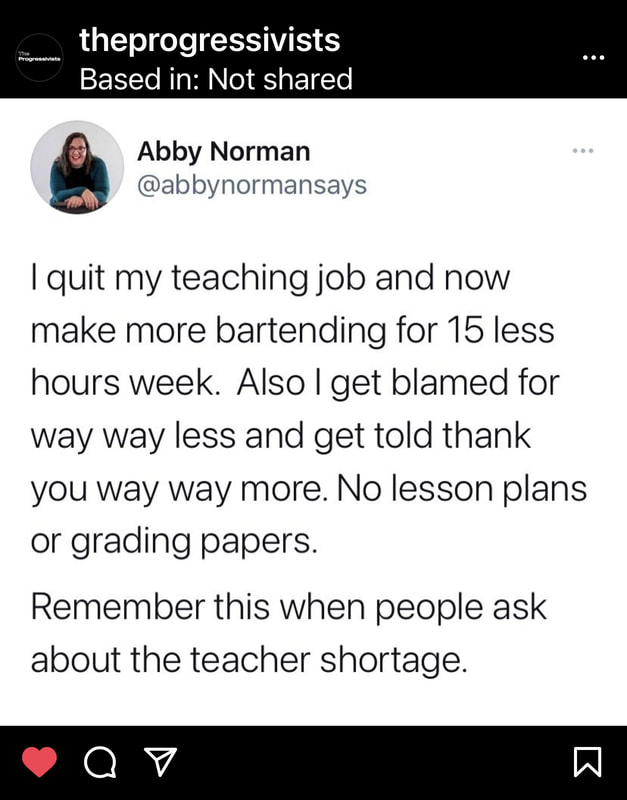

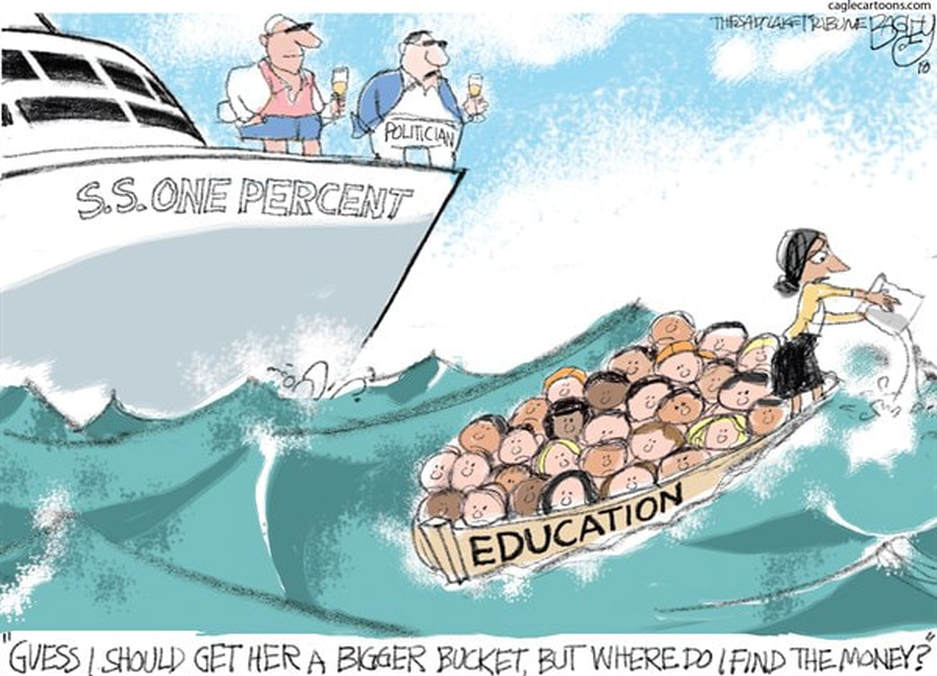

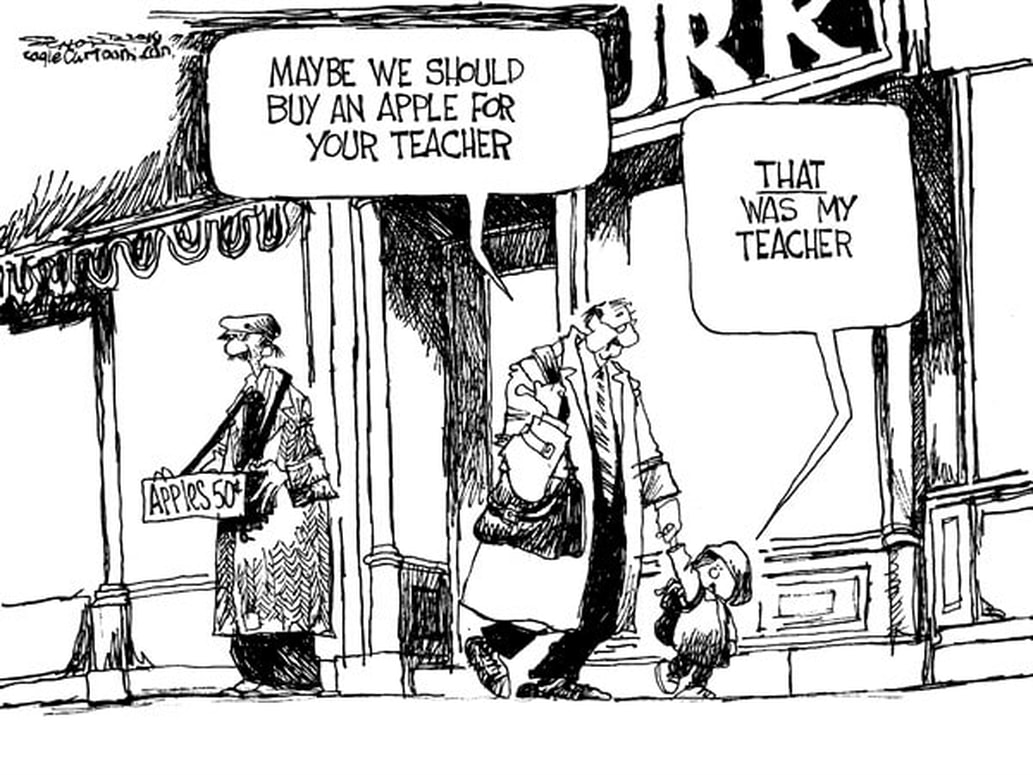

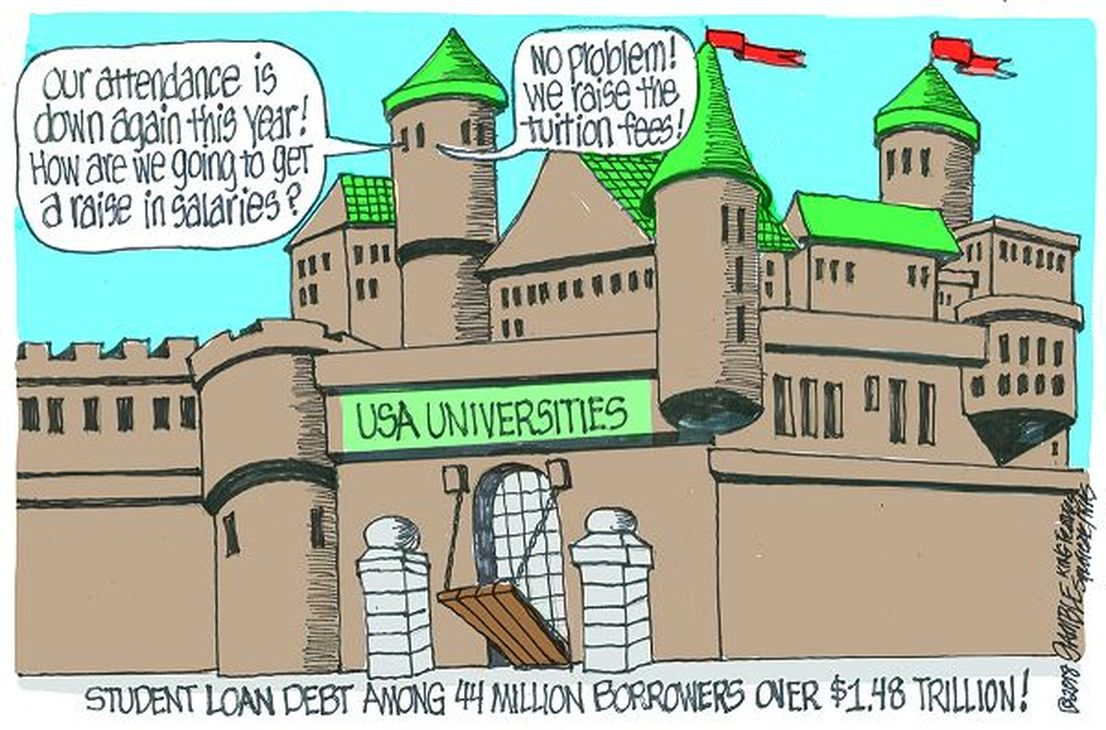

For many teachers, this year’s uprising is decades in the making. The country’s roughly 3.2 million full-time public-school teachers (kindergarten through high school) are experiencing some of the worst wage stagnation of any profession, earning less on average, in inflation-adjusted dollars, than they did in 1990, according to Department of Education (DOE) data.

Meanwhile, the pay gap between teachers and other comparably educated professionals is now the largest on record. In 1994, public-school teachers in the U.S. earned 1.8% less per week than comparable workers, according to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a left-leaning think tank. By last year, they made 18.7% less. The situation is particularly grim in states such as Oklahoma, where teachers’ inflation-adjusted salaries actually decreased by about $8,000 in the last decade, to an average of $45,245 in 2016, according to DOE data. In Arizona, teachers’ average inflation-adjusted annual wages are down $5,000.

http://time.com/longform/teaching-in-america/?xid=time_socialflow_twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=time

Racist and sexist depictions of human evolution still permeate science, education and popular culture today

The Conversation - raw story

April 05, 2023

Systemic racism and sexism have permeated civilization since the rise of agriculture, when people started living in one place for a long time. Early Western scientists, such as Aristotle in ancient Greece, were indoctrinated with the ethnocentric and misogynistic narratives that permeated their society. More than 2,000 years after Aristotle’s writings, English naturalist Charles Darwin also extrapolated the sexist and racist narratives he heard and read in his youth to the natural world.

Darwin presented his biased views as scientific facts, such as in his 1871 book “The Descent of Man,” where he described his belief that men are evolutionarily superior to women, Europeans superior to non-Europeans and hierarchical civilizations superior to small egalitarian societies. In that book, which continues to be studied in schools and natural history museums, he considered “the hideous ornaments and the equally hideous music admired by most savages” to be “not so highly developed as in certain animals, for instance, in birds,” and compared the appearance of Africans to the New World monkey Pithecia satanas.

Science isn’t immune to sexism and racism.

“The Descent of Man” was published during a moment of societal turmoil in continental Europe. In France, the working class Paris Commune took to the streets asking for radical social change, including the overturning of societal hierarchies. Darwin’s claims that the subjugation of the poor, non-Europeans and women was the natural result of evolutionary progress were music to the ears of the elites and those in power within academia. Science historian Janet Browne wrote that Darwin’s meteoric rise within Victorian society did not occur despite his racist and sexist writings but in great part because of them.

It is not coincidence that Darwin had a state funeral in Westminster Abbey, an honor emblematic of English power, and was publicly commemorated as a symbol of “English success in conquering nature and civilizing the globe during Victoria’s long reign.”

Despite the significant societal changes that have occurred in the last 150 years, sexist and racist narratives are still common in science, medicine and education. As a teacher and researcher at Howard University, I am interested in combining my main fields of study, biology and anthropology, to discuss broader societal issues. In research I recently published with my colleague Fatimah Jackson and three medical students at Howard University, we show how racist and sexist narratives are not a thing of the past: They are still present in scientific papers, textbooks, museums and educational materials.

From museums to scientific papers

One example of how biased narratives are still present in science today is the numerous depictions of human evolution as a linear trend from darker and more “primitive” human beings to more “evolved” ones with a lighter skin tone. Natural history museums, websites and UNESCO heritage sites have all shown this trend.

The fact that such depictions are not scientifically accurate does not discourage their continued circulation. Roughly 11% of people living today are “white,” or European descendants. Images showing a linear progression to whiteness do not accurately represent either human evolution or what living humans look like today, as a whole. Furthermore, there is no scientific evidence supporting a progressive skin whitening. Lighter skin pigmentation chiefly evolved within just a few groups that migrated to non-African regions with high or low latitudes, such as the northern regions of America, Europe and Asia.

Illustrations of human evolution tend to depict progressive skin whitening.

Sexist narratives also still permeate academia. For example, in a 2021 paper on a famous early human fossil found in the Sierra de Atapuerca archaeological site in Spain, researchers examined the canine teeth of the remains and found that it was actually that of a girl between 9 and 11 years old. It was previously believed that the fossil was a boy due to a popular 2002 book by one of the authors of that paper, paleoanthropologist José María Bermúdez de Castro. What is particularly telling is that the study authors recognized that there was no scientific reason for the fossil remains to have been designated as a male in the first place. The decision, they wrote, “arose randomly.”

But these choices are not truly “random.” Depictions of human evolution frequently only show men. In the few cases where women are depicted, they tend to be shown as passive mothers, not as active inventors, cave painters or food gatherers, despite available anthropological data showing that pre-historical women were all those things.

Another example of sexist narratives in science is how researchers continue to discuss the “puzzling” evolution of the female orgasm. Darwin constructed narratives about how women were evolutionarily “coy” and sexually passive, even though he acknowledged that females actively select their sexual partners in most mammalian species. As a Victorian, it was difficult for him to accept that women could play an active part in choosing a partner, so he argued that such roles only applied to women in early human evolution. According to Darwin, men later began to sexually select women.

Sexist narratives about women being more “coy” and “less sexual,” including the idea of the female orgasm as an evolutionary puzzle, are contradicted by a wide range of evidence. For instance, women are the ones who actually more frequently experience multiple orgasms as well as more complex, elaborate and intense orgasms on average, compared to men. Women are not biologically less sexual, but sexist stereotypes were accepted as scientific fact.

The vicious cycle of systemic racism and sexism

Educational materials, including textbooks and anatomical atlases used by science and medical students, play a crucial role in perpetuating biased narratives. For example, the 2017 edition of “Netter Atlas of Human Anatomy,” commonly used by medical students and clinical professionals, includes about 180 figures that show skin color. Of those, the vast majority show male individuals with white skin, and only two show individuals with “darker” skin.

This perpetuates the depiction of white men as the anatomical prototype of the human species and fails to display the full anatomical diversity of people.

Textbooks and educational materials can perpetuate the biases of their creators in science and society.

Authors of teaching materials for children also replicate the biases in scientific publications, museums and textbooks. For example, the cover of a 2016 coloring book entitled “The Evolution of Living Things”“ shows human evolution as a linear trend from darker "primitive” creatures to a “civilized” Western man. Indoctrination comes full circle when the children using such books become scientists, journalists, museum curators, politicians, authors or illustrators.

One of the key characteristics of systemic racism and sexism is that it is unconsciously perpetuated by people who often don’t realize that the narratives and choices they make are biased. Academics can address long-standing racist, sexist and Western-centric biases by being both more alert and proactive in detecting and correcting these influences in their work. Allowing inaccurate narratives to continue to circulate in science, medicine, education and the media perpetuates not only these narratives in future generations, but also the discrimination, oppression and atrocities that have been justified by them in the past.

Darwin presented his biased views as scientific facts, such as in his 1871 book “The Descent of Man,” where he described his belief that men are evolutionarily superior to women, Europeans superior to non-Europeans and hierarchical civilizations superior to small egalitarian societies. In that book, which continues to be studied in schools and natural history museums, he considered “the hideous ornaments and the equally hideous music admired by most savages” to be “not so highly developed as in certain animals, for instance, in birds,” and compared the appearance of Africans to the New World monkey Pithecia satanas.

Science isn’t immune to sexism and racism.

“The Descent of Man” was published during a moment of societal turmoil in continental Europe. In France, the working class Paris Commune took to the streets asking for radical social change, including the overturning of societal hierarchies. Darwin’s claims that the subjugation of the poor, non-Europeans and women was the natural result of evolutionary progress were music to the ears of the elites and those in power within academia. Science historian Janet Browne wrote that Darwin’s meteoric rise within Victorian society did not occur despite his racist and sexist writings but in great part because of them.

It is not coincidence that Darwin had a state funeral in Westminster Abbey, an honor emblematic of English power, and was publicly commemorated as a symbol of “English success in conquering nature and civilizing the globe during Victoria’s long reign.”

Despite the significant societal changes that have occurred in the last 150 years, sexist and racist narratives are still common in science, medicine and education. As a teacher and researcher at Howard University, I am interested in combining my main fields of study, biology and anthropology, to discuss broader societal issues. In research I recently published with my colleague Fatimah Jackson and three medical students at Howard University, we show how racist and sexist narratives are not a thing of the past: They are still present in scientific papers, textbooks, museums and educational materials.

From museums to scientific papers

One example of how biased narratives are still present in science today is the numerous depictions of human evolution as a linear trend from darker and more “primitive” human beings to more “evolved” ones with a lighter skin tone. Natural history museums, websites and UNESCO heritage sites have all shown this trend.

The fact that such depictions are not scientifically accurate does not discourage their continued circulation. Roughly 11% of people living today are “white,” or European descendants. Images showing a linear progression to whiteness do not accurately represent either human evolution or what living humans look like today, as a whole. Furthermore, there is no scientific evidence supporting a progressive skin whitening. Lighter skin pigmentation chiefly evolved within just a few groups that migrated to non-African regions with high or low latitudes, such as the northern regions of America, Europe and Asia.

Illustrations of human evolution tend to depict progressive skin whitening.

Sexist narratives also still permeate academia. For example, in a 2021 paper on a famous early human fossil found in the Sierra de Atapuerca archaeological site in Spain, researchers examined the canine teeth of the remains and found that it was actually that of a girl between 9 and 11 years old. It was previously believed that the fossil was a boy due to a popular 2002 book by one of the authors of that paper, paleoanthropologist José María Bermúdez de Castro. What is particularly telling is that the study authors recognized that there was no scientific reason for the fossil remains to have been designated as a male in the first place. The decision, they wrote, “arose randomly.”

But these choices are not truly “random.” Depictions of human evolution frequently only show men. In the few cases where women are depicted, they tend to be shown as passive mothers, not as active inventors, cave painters or food gatherers, despite available anthropological data showing that pre-historical women were all those things.

Another example of sexist narratives in science is how researchers continue to discuss the “puzzling” evolution of the female orgasm. Darwin constructed narratives about how women were evolutionarily “coy” and sexually passive, even though he acknowledged that females actively select their sexual partners in most mammalian species. As a Victorian, it was difficult for him to accept that women could play an active part in choosing a partner, so he argued that such roles only applied to women in early human evolution. According to Darwin, men later began to sexually select women.

Sexist narratives about women being more “coy” and “less sexual,” including the idea of the female orgasm as an evolutionary puzzle, are contradicted by a wide range of evidence. For instance, women are the ones who actually more frequently experience multiple orgasms as well as more complex, elaborate and intense orgasms on average, compared to men. Women are not biologically less sexual, but sexist stereotypes were accepted as scientific fact.

The vicious cycle of systemic racism and sexism

Educational materials, including textbooks and anatomical atlases used by science and medical students, play a crucial role in perpetuating biased narratives. For example, the 2017 edition of “Netter Atlas of Human Anatomy,” commonly used by medical students and clinical professionals, includes about 180 figures that show skin color. Of those, the vast majority show male individuals with white skin, and only two show individuals with “darker” skin.

This perpetuates the depiction of white men as the anatomical prototype of the human species and fails to display the full anatomical diversity of people.

Textbooks and educational materials can perpetuate the biases of their creators in science and society.

Authors of teaching materials for children also replicate the biases in scientific publications, museums and textbooks. For example, the cover of a 2016 coloring book entitled “The Evolution of Living Things”“ shows human evolution as a linear trend from darker "primitive” creatures to a “civilized” Western man. Indoctrination comes full circle when the children using such books become scientists, journalists, museum curators, politicians, authors or illustrators.

One of the key characteristics of systemic racism and sexism is that it is unconsciously perpetuated by people who often don’t realize that the narratives and choices they make are biased. Academics can address long-standing racist, sexist and Western-centric biases by being both more alert and proactive in detecting and correcting these influences in their work. Allowing inaccurate narratives to continue to circulate in science, medicine, education and the media perpetuates not only these narratives in future generations, but also the discrimination, oppression and atrocities that have been justified by them in the past.

Decades of Racial Bias Preceded College Board’s AP Black History Course Changes

The College Board still seems to feel comfortable disappearing the Black educational experience.

By Ngakiya Camara , TRUTHOUT

Published February 16, 2023

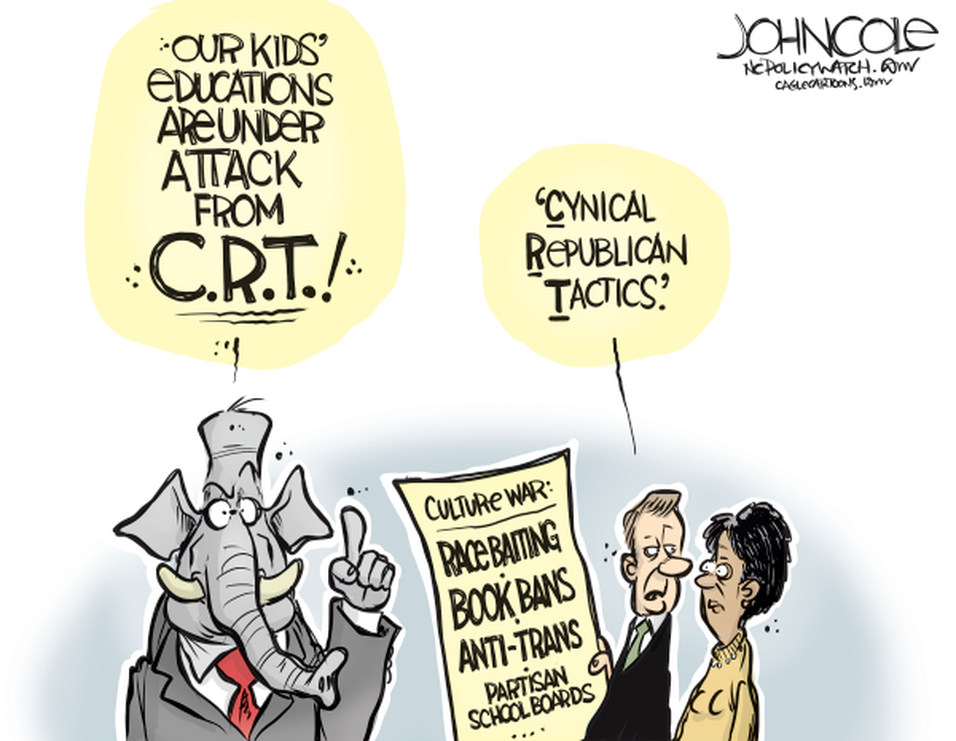

For weeks, prominent scholars and educators, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, Kimberlé Crenshaw and David J. Johns, have called out the College Board for removing contemporary topics and scholarship in Black history from the new Advanced Placement (AP) African American History course being piloted across 60 U.S. schools. Some of these revisions — regarding topics like Black Lives Matter, mass incarceration and reparations — were the same topics of concern outlined in a letter leaked by the Florida Department of Education, which described the College Board’s consistent contact with the DeSantis administration regarding the AP course structure. However, in two separate letters, the College Board denied revising the course on behalf of Gov. Ron DeSantis. The College Board declared instead that the rollout was predetermined, and that Florida’s administration merely sought to claim a nonexistent political victory “by taking credit retroactively for changes we ourselves made but that they never suggested to us.”

Despite the College Board having effectively “set the record straight” in their robust denial of negotiating with Florida’s administration about the course’s content, they have simultaneously made it clear that the revised framework isn’t exactly going anywhere either. This includes downgrading originally required topics like structural racism, racial capitalism, mass incarceration, reparations, intersectionality and Black Lives Matter to now be optional, while introducing research topics like Black conservatism. And while the College Board’s president claims that the removal of works by contemporary Black scholars was because the sources would have been “quite dense” for students, Black educators across the country have a different, more valid theory. Ronda Taylor Bullock, a former teacher and head of the nonprofit anti-racist education center called “we are,” argues that these revisions are the erasure of Black voices and history. The College Board is “cowering to white supremacy — cowering to political power, versus recognizing the academic merits of how the curriculum was from the beginning,” Bullock said.

In fact, cowering to white supremacy and political power may be easy for the College Board because it is an institution forged from racism and eugenics, and designed to preserve higher education for the white, wealthy and privileged. And today, it continues to work exactly the way it was initially intended.

An Instrument of Racism

The College Board is the lucrative nonprofit at the forefront of the college entrance exam establishment and it administers SAT and AP exams. Such exams, especially the SATs, have historically been used by colleges across the country to determine students’ learning capabilities and predict how well they will do in higher education. However, Ibram X. Kendi, Black scholar and author of How to Be an Antiracist, emphasizes that since their inception, standardized tests have been an instrument of racism: “[T]o tell the truth about standardized tests is to tell the story of the eugenicists who created and popularized these tests in the United States more than a century ago.”

In fact, the College Board adopted the SAT test from infamous eugenicist Carl Brigham based on his illusory publication A Study of American Intelligence in 1923, which decried Black people as the lowest on the racial, ethnic and cultural spectrum, and warned of the infiltration of non-white people into white spaces. The resulting exam Brigham developed sought to assess “aptitude for learning” rather than acquired knowledge, which appealed to eugenicists because this aptitude was seen as innate intelligence and thus deeply entrenched with one’s ethnic origins. As a result, aptitude tests could be used to limit the admissions of particular ethnicities deemed “lesser than,” including Black people and Jewish students, especially from Ivy Leagues. Fast-forward to today, the SAT is still accepted as the reliable evaluation for intellectual merit.

However, according to scholars Saul Geiser and Richard Atkinson, it is student GPA (irrespective of the quality of school attended) that is the better predictor of short- and long-term college outcomes. They emphasize that SAT scores actually correlate most with family income and parents’ education — so much so that the supposed predictive power of the SAT signifies the proxy effects of socioeconomic status. High school grades, on the other hand, are less indicative of socioeconomic status, and demonstrate more predictive power of college performance than the SAT even when controls for socioeconomic status are introduced. As a result, prioritizing high school performance over standardized test scores is more equitable, and would expand college opportunities for low-income and marginalized students.

Instead, Black and Latino students bear the brunt of a discriminatory standardized test system, with only 20 percent of Black students and 29 percent of Latino students meeting the benchmark for reading, writing and math portions of the test compared to 57 percent of white students. And these groups bear the brunt for many reasons. In fact, according to scholar Joseph A. Soares, biased test question selection algorithms structurally discriminate against Black people. He argues that, since experimental questions are given to students before the test’s administration, those practice questions where Black students outperform white students are removed so as to maintain the standard bell curve.

Furthermore, the college entry exam business — which includes payments per exam taken, exam prep courses, tutoring, and more — is a multibillion-dollar industry which exploits both parent and student desperation for successful higher education outcomes. As a result, these tests favor white and wealthy test-takers who can not only afford to pay the $60 for each test, but can also spend thousands on prep courses and tutoring, which is one of the only ways to actually improve test scores. This is not an option for poor marginalized folks, who barely have access to nearby SAT testing sites in their areas, let alone money to pay for a weekly SAT tutor.

The College Board’s Advanced Placement program — the system offering the new African American studies course — is yet another instrument of white supremacy which disguises inequity under the facade of intellectual exceptionalism. The AP program, which is said to provide advanced educational opportunities for thriving students, persistently grapples with a lack of Black student enrollment. In fact, Black students account for only 9 percent of AP students nationally despite making up 15 percent of the U.S. population. Access to AP classes remain limited for marginalized students whose schools either do not have AP courses available, or because discriminatory practices can particularly hinder Black and Brown students from enrolling in classes when they are available. Such practices include educator bias in recommending students for courses, admission policies that center students’ past achievements over their interests and ambitions and the failure to communicate with marginalized students about AP’s availability to them.

Feeling unwelcome in AP spaces is yet another prominent reason why marginalized folks may be under-enrolled within the courses. Such is the reason why courses like African American history are crucial, as they not only demonstrate a large portion of erased U.S. history, but they also reflect the real, lived experiences of Black students. Courses like these meet marginalized students where they are and create a space through which they can process and articulate such experiences. However, analyzing Black history through the Advanced Placement framework requires a deep reflection of the College Board system itself, which still seems to feel comfortable disappearing Black educational experience even as it establishes a meaningful curriculum.

Despite the College Board having effectively “set the record straight” in their robust denial of negotiating with Florida’s administration about the course’s content, they have simultaneously made it clear that the revised framework isn’t exactly going anywhere either. This includes downgrading originally required topics like structural racism, racial capitalism, mass incarceration, reparations, intersectionality and Black Lives Matter to now be optional, while introducing research topics like Black conservatism. And while the College Board’s president claims that the removal of works by contemporary Black scholars was because the sources would have been “quite dense” for students, Black educators across the country have a different, more valid theory. Ronda Taylor Bullock, a former teacher and head of the nonprofit anti-racist education center called “we are,” argues that these revisions are the erasure of Black voices and history. The College Board is “cowering to white supremacy — cowering to political power, versus recognizing the academic merits of how the curriculum was from the beginning,” Bullock said.

In fact, cowering to white supremacy and political power may be easy for the College Board because it is an institution forged from racism and eugenics, and designed to preserve higher education for the white, wealthy and privileged. And today, it continues to work exactly the way it was initially intended.

An Instrument of Racism

The College Board is the lucrative nonprofit at the forefront of the college entrance exam establishment and it administers SAT and AP exams. Such exams, especially the SATs, have historically been used by colleges across the country to determine students’ learning capabilities and predict how well they will do in higher education. However, Ibram X. Kendi, Black scholar and author of How to Be an Antiracist, emphasizes that since their inception, standardized tests have been an instrument of racism: “[T]o tell the truth about standardized tests is to tell the story of the eugenicists who created and popularized these tests in the United States more than a century ago.”

In fact, the College Board adopted the SAT test from infamous eugenicist Carl Brigham based on his illusory publication A Study of American Intelligence in 1923, which decried Black people as the lowest on the racial, ethnic and cultural spectrum, and warned of the infiltration of non-white people into white spaces. The resulting exam Brigham developed sought to assess “aptitude for learning” rather than acquired knowledge, which appealed to eugenicists because this aptitude was seen as innate intelligence and thus deeply entrenched with one’s ethnic origins. As a result, aptitude tests could be used to limit the admissions of particular ethnicities deemed “lesser than,” including Black people and Jewish students, especially from Ivy Leagues. Fast-forward to today, the SAT is still accepted as the reliable evaluation for intellectual merit.

However, according to scholars Saul Geiser and Richard Atkinson, it is student GPA (irrespective of the quality of school attended) that is the better predictor of short- and long-term college outcomes. They emphasize that SAT scores actually correlate most with family income and parents’ education — so much so that the supposed predictive power of the SAT signifies the proxy effects of socioeconomic status. High school grades, on the other hand, are less indicative of socioeconomic status, and demonstrate more predictive power of college performance than the SAT even when controls for socioeconomic status are introduced. As a result, prioritizing high school performance over standardized test scores is more equitable, and would expand college opportunities for low-income and marginalized students.

Instead, Black and Latino students bear the brunt of a discriminatory standardized test system, with only 20 percent of Black students and 29 percent of Latino students meeting the benchmark for reading, writing and math portions of the test compared to 57 percent of white students. And these groups bear the brunt for many reasons. In fact, according to scholar Joseph A. Soares, biased test question selection algorithms structurally discriminate against Black people. He argues that, since experimental questions are given to students before the test’s administration, those practice questions where Black students outperform white students are removed so as to maintain the standard bell curve.

Furthermore, the college entry exam business — which includes payments per exam taken, exam prep courses, tutoring, and more — is a multibillion-dollar industry which exploits both parent and student desperation for successful higher education outcomes. As a result, these tests favor white and wealthy test-takers who can not only afford to pay the $60 for each test, but can also spend thousands on prep courses and tutoring, which is one of the only ways to actually improve test scores. This is not an option for poor marginalized folks, who barely have access to nearby SAT testing sites in their areas, let alone money to pay for a weekly SAT tutor.

The College Board’s Advanced Placement program — the system offering the new African American studies course — is yet another instrument of white supremacy which disguises inequity under the facade of intellectual exceptionalism. The AP program, which is said to provide advanced educational opportunities for thriving students, persistently grapples with a lack of Black student enrollment. In fact, Black students account for only 9 percent of AP students nationally despite making up 15 percent of the U.S. population. Access to AP classes remain limited for marginalized students whose schools either do not have AP courses available, or because discriminatory practices can particularly hinder Black and Brown students from enrolling in classes when they are available. Such practices include educator bias in recommending students for courses, admission policies that center students’ past achievements over their interests and ambitions and the failure to communicate with marginalized students about AP’s availability to them.

Feeling unwelcome in AP spaces is yet another prominent reason why marginalized folks may be under-enrolled within the courses. Such is the reason why courses like African American history are crucial, as they not only demonstrate a large portion of erased U.S. history, but they also reflect the real, lived experiences of Black students. Courses like these meet marginalized students where they are and create a space through which they can process and articulate such experiences. However, analyzing Black history through the Advanced Placement framework requires a deep reflection of the College Board system itself, which still seems to feel comfortable disappearing Black educational experience even as it establishes a meaningful curriculum.

Trans Students and Their Teachers Face a School Year Full of Terrifying New Laws

BY Orion Rummler, The 19th

PUBLISHED September 1, 2022

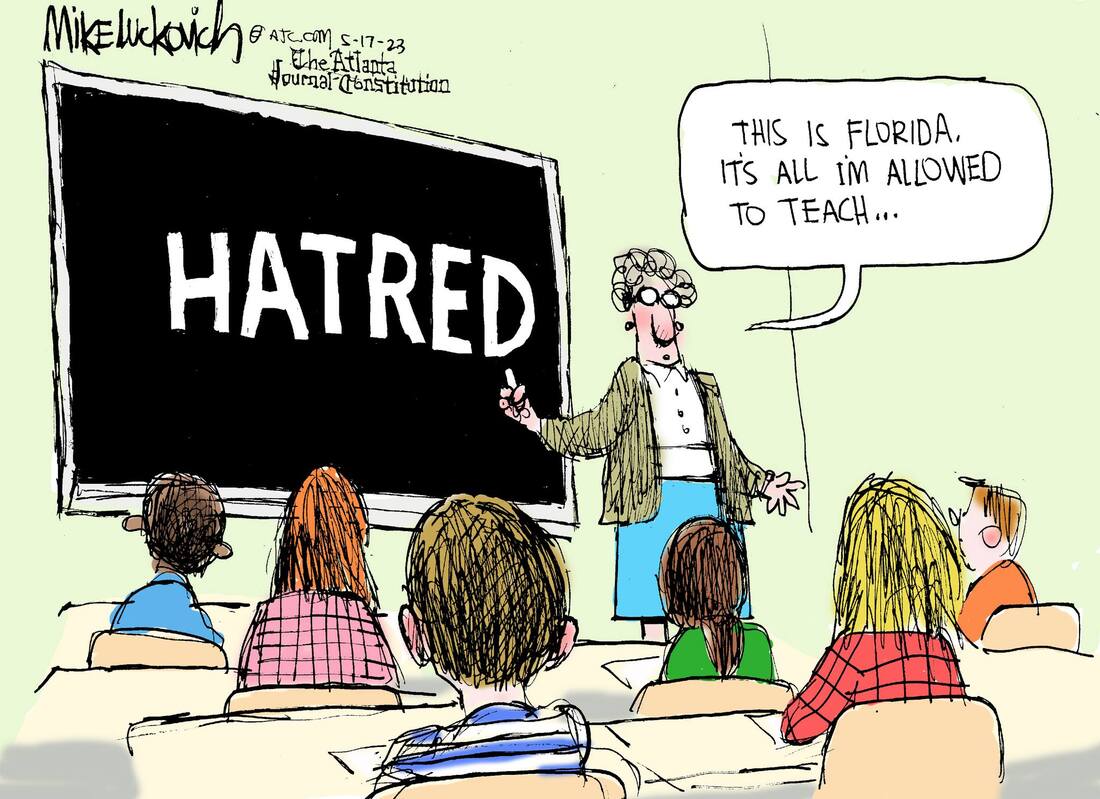

Anita Hatcher, a seventh-grade English language arts teacher in the Florida Panhandle, worries what this school year will bring for her transgender students.

She’s not alone.

Trans students and their teachers in Florida, Alabama and Texas — three states where legislators and governors’ offices have been the most vocal in efforts to restrict trans youths’ access to bathrooms and gender-affirming care, on top of education restrictions and sports bans — are worried about what the new school year may bring.

“I’m most worried about the first time I take up a written test and someone’s name doesn’t match what’s on my roster,” said Hatcher, whose classes began August 10. She’s also worried about respecting her trans students’ names and identities — without outing them. “How can I call on a student, show them respect, be equitable, not out them, involve them in class discussion?”

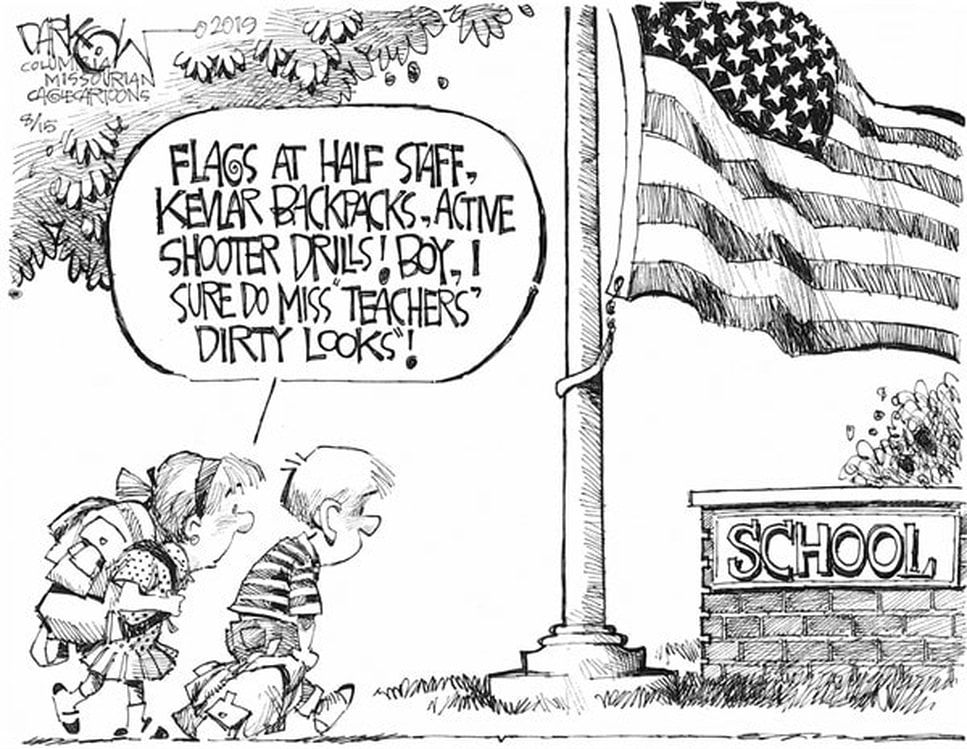

Florida’s law restricting classroom discussion on gender and sexuality, nicknamed “Don’t Say Gay” by advocates, went into effect in early July. It faces a lawsuit from Equality Florida backed by attorneys general from 16 states. While the bill’s explicit limitations apply to students through third grade, additional language in the bill mandates “age-appropriate and developmentally appropriate” lessons, which advocates say could affect LGBTQ+ students in higher grade levels.

For Hatcher, the fear among teachers in Florida is palpable and is even pushing some educators to leave, exacerbating a teacher shortage. Her school follows guidance set by Leon County, and she’s worried that even policies meant to be inclusive will out her transgender students. If a trans child uses a locker room or restroom that matches their gender identity, which the school district stresses that students are allowed to do, then their peers’ parents may be warned in writing: “A student who is open about their gender identity may be in your child’s Physical Education class or extra/co-curricular activity.”

That note would not be sent if the family has sought privacy about their child’s identity and accepted other accommodations “that will provide privacy for all students.” The guide does not define what such accommodations would be offered. Hatcher said that there hasn’t been training provided to faculty or staff at her school on the guide.

“Not every child is out at home before they’re out at school,” said Hatcher, who was a plaintiff in Equality Florida’s initial Don’t Say Gay lawsuit. With some of her own students, she has known about their LGBTQ+ identity before their parents. The Leon County school district did not respond to a request for comment.

In Alabama, a bathroom bill that also went into effect July 1 prohibits public schools from allowing classroom discussion on sexual orientation or gender identity for kindergarteners up to fifth grade. A separate Alabama law requires school counselors and teachers to tell parents if their child comes out as trans or gender-nonconforming.

Harleigh Walker, a 15-year-old trans girl at Auburn High School, is starting tenth grade this year. She’s worried about her other transgender friends’ mental health and safety, especially those who aren’t out to their parents — and about what could happen if her friends accidentally say the wrong thing near a teacher or counselor.

“I just don’t want to see a whole bunch of these trans kids going through possibly being outed to their parents,” she said.

Walker started classes August 9. So far, she hasn’t seen any incidents around bathroom or locker room access and is feeling optimistic. But, she also expects her school and others to get more strict as the year progresses.

When asked what policies have been put in place in response to recent anti-trans laws, Auburn High School principal Shannon Pignato said in a statement that “educators are not required to initiate contact with parents,” but “if a student discloses information, open communication among stakeholders is considered a priority especially in matters of mental health and safety.” Pignato did not respond when asked what information or stakeholders she was referring to.

In Alabama and Florida, individual teachers are being tasked with finding where to draw the line in response to new state laws as their school districts update policies and grapple with what those laws mean in practice.

A 13-year-old nonbinary transmasculine student in Birmingham, Alabama, who asked to be anonymous because he’s afraid that speaking publicly would make current bullying worse, said that his physical education teacher is not letting any students use the locker rooms during class right now — because he wants to use the boys’ locker rooms.

“It’s just really stupid and they’re making a giant deal out of it,” he said, adding that the situation has made him feel singled out by a teacher who has otherwise been supportive and who has tried to use his correct name and pronouns. The decision was explained to him privately during their second PE class, he said. When he went to see his counselor to address the issue, she explained that the school, which is privately run, planned to have further discussions on what to do.

Joseph Rawlins, who teaches special education at Atlantic Coast High School, a public school in Jacksonville, Florida, also oversees the school’s Gender and Sexuality Alliance. The GSA meets regularly virtually on Microsoft Teams and in-person twice a month — with its first meeting this year scheduled for Thursday.

Under the state’s new laws, Rawlins has to figure out how to affirm and protect trans students in his classroom — as well as within a club that is meant to give LGBTQ+ students a place to be themselves and to freely talk about their identities.

“What’s the point of a GSA if I can’t make it a safe space?” he said. It’s difficult to know what is and isn’t safe to share for students who don’t want to be out to their families or to the rest of the school — including their name and pronouns. It’s also unclear when teachers are obligated to call home to report a student, although his district in Duval County has finalized new rules in its student support guide.

In a draft version of the Duval County school rules released in May and reviewed by The 19th, student ID cards can be updated to reflect a student’s name that affirms their gender identity — after the parent has been notified. The same rule applies to class rosters, yearbooks, and school newspapers. Atlantic Coast’s principal declined to comment on the school’s policies over email.

The line that must be crossed to alert a student’s family, in Rawlins’ mind, is if a student asks for a roster change or for their yearbook to be updated with their preferred name — anything that has a digital or paper record. Figuring out the rules of engagement is even harder considering the law went into effect only a month ago, but Rawlins said he feels supported by his school and the district in trying to untangle the mess.

Now, when students send emails to teachers before classes start explaining their name and pronouns — and when that name doesn’t match the legal name on the class roster — they’re potentially incriminating themselves, Rawlins said. Before classes began August 15, one student sent an email to eight teachers alerting them to his name and pronouns — and made it clear that his family does not support addressing him that way, Rawlins said.

“Well, now what do we do? Because a kid has sent through a public school email system, now it’s a matter of public record that they want to go by these pronouns, they want to use this name. But they don’t want parents to find out,” he said.

Those scenarios are prompting teachers like Rawlins to ask their students if they are sure that they want to follow through with what they’re asking for — to be acknowledged and affirmed in their gender identity — and if they understand what Florida’s law says.

“It’s just tough,” he said. “For some of them, it’s fine, because they’ve got supportive families. For those kids, things are actually going pretty well this year. … But for those who don’t have a supportive household, it’s tough right now.”

In Texas, the legislative body is out of session after introducing more than 40 bills targeting transgender youth last year, out of which only one passed into law. And at the local level, efforts to restrict education are making headway. A school district in Grapevine, Texas, recently voted to require students to use bathrooms dictated by their sex assigned at birth and to encourage teachers to ignore students’ requests on using their current pronouns, the Texas Tribune reports.

For one 16-year-old trans girl with a supportive family who’s starting her junior year in Austin’s Independent School District, this year marks feeling more confident — in her sense of style, in having more friends and being more able to express herself after transitioning during pandemic school shutdowns. She asked to be anonymous due to Texas’ attempts to criminalize families that obtain gender-affirming care for trans minors.

She feels safe at her school largely due to supportive teachers and friends — and because not many of the people she knows at school know or care that she is transgender. This year, teachers asked students to fill out a Google doc with their pronouns and preferred name — and if those are the same at home and at school. That helped her feel at ease.

“I am worried about other kids who aren’t as well off or as privileged as me,” she said. “If there’s a kid and they’re trans, but they’re not out to their parents or they haven’t had that gender marker change or the name change … it’s hard to go through school while also being validated and just respected.”

Jason Stanford, spokesperson for the Austin school district, said that the district aims to be welcoming for LGBTQ+ and trans students, who should be able to use bathrooms according to their gender identity, or single-stall facilities if that student is worried about bullying.

“If I have to choose between an angry parent and making a kid feel safe, me and everyone I work with is going to make the same choice,” he said. “I think too often in these discussions, we center the emotional security of adults at the expense of children.”

She’s not alone.

Trans students and their teachers in Florida, Alabama and Texas — three states where legislators and governors’ offices have been the most vocal in efforts to restrict trans youths’ access to bathrooms and gender-affirming care, on top of education restrictions and sports bans — are worried about what the new school year may bring.

“I’m most worried about the first time I take up a written test and someone’s name doesn’t match what’s on my roster,” said Hatcher, whose classes began August 10. She’s also worried about respecting her trans students’ names and identities — without outing them. “How can I call on a student, show them respect, be equitable, not out them, involve them in class discussion?”

Florida’s law restricting classroom discussion on gender and sexuality, nicknamed “Don’t Say Gay” by advocates, went into effect in early July. It faces a lawsuit from Equality Florida backed by attorneys general from 16 states. While the bill’s explicit limitations apply to students through third grade, additional language in the bill mandates “age-appropriate and developmentally appropriate” lessons, which advocates say could affect LGBTQ+ students in higher grade levels.

For Hatcher, the fear among teachers in Florida is palpable and is even pushing some educators to leave, exacerbating a teacher shortage. Her school follows guidance set by Leon County, and she’s worried that even policies meant to be inclusive will out her transgender students. If a trans child uses a locker room or restroom that matches their gender identity, which the school district stresses that students are allowed to do, then their peers’ parents may be warned in writing: “A student who is open about their gender identity may be in your child’s Physical Education class or extra/co-curricular activity.”

That note would not be sent if the family has sought privacy about their child’s identity and accepted other accommodations “that will provide privacy for all students.” The guide does not define what such accommodations would be offered. Hatcher said that there hasn’t been training provided to faculty or staff at her school on the guide.

“Not every child is out at home before they’re out at school,” said Hatcher, who was a plaintiff in Equality Florida’s initial Don’t Say Gay lawsuit. With some of her own students, she has known about their LGBTQ+ identity before their parents. The Leon County school district did not respond to a request for comment.

In Alabama, a bathroom bill that also went into effect July 1 prohibits public schools from allowing classroom discussion on sexual orientation or gender identity for kindergarteners up to fifth grade. A separate Alabama law requires school counselors and teachers to tell parents if their child comes out as trans or gender-nonconforming.

Harleigh Walker, a 15-year-old trans girl at Auburn High School, is starting tenth grade this year. She’s worried about her other transgender friends’ mental health and safety, especially those who aren’t out to their parents — and about what could happen if her friends accidentally say the wrong thing near a teacher or counselor.

“I just don’t want to see a whole bunch of these trans kids going through possibly being outed to their parents,” she said.

Walker started classes August 9. So far, she hasn’t seen any incidents around bathroom or locker room access and is feeling optimistic. But, she also expects her school and others to get more strict as the year progresses.

When asked what policies have been put in place in response to recent anti-trans laws, Auburn High School principal Shannon Pignato said in a statement that “educators are not required to initiate contact with parents,” but “if a student discloses information, open communication among stakeholders is considered a priority especially in matters of mental health and safety.” Pignato did not respond when asked what information or stakeholders she was referring to.

In Alabama and Florida, individual teachers are being tasked with finding where to draw the line in response to new state laws as their school districts update policies and grapple with what those laws mean in practice.

A 13-year-old nonbinary transmasculine student in Birmingham, Alabama, who asked to be anonymous because he’s afraid that speaking publicly would make current bullying worse, said that his physical education teacher is not letting any students use the locker rooms during class right now — because he wants to use the boys’ locker rooms.

“It’s just really stupid and they’re making a giant deal out of it,” he said, adding that the situation has made him feel singled out by a teacher who has otherwise been supportive and who has tried to use his correct name and pronouns. The decision was explained to him privately during their second PE class, he said. When he went to see his counselor to address the issue, she explained that the school, which is privately run, planned to have further discussions on what to do.

Joseph Rawlins, who teaches special education at Atlantic Coast High School, a public school in Jacksonville, Florida, also oversees the school’s Gender and Sexuality Alliance. The GSA meets regularly virtually on Microsoft Teams and in-person twice a month — with its first meeting this year scheduled for Thursday.

Under the state’s new laws, Rawlins has to figure out how to affirm and protect trans students in his classroom — as well as within a club that is meant to give LGBTQ+ students a place to be themselves and to freely talk about their identities.

“What’s the point of a GSA if I can’t make it a safe space?” he said. It’s difficult to know what is and isn’t safe to share for students who don’t want to be out to their families or to the rest of the school — including their name and pronouns. It’s also unclear when teachers are obligated to call home to report a student, although his district in Duval County has finalized new rules in its student support guide.

In a draft version of the Duval County school rules released in May and reviewed by The 19th, student ID cards can be updated to reflect a student’s name that affirms their gender identity — after the parent has been notified. The same rule applies to class rosters, yearbooks, and school newspapers. Atlantic Coast’s principal declined to comment on the school’s policies over email.

The line that must be crossed to alert a student’s family, in Rawlins’ mind, is if a student asks for a roster change or for their yearbook to be updated with their preferred name — anything that has a digital or paper record. Figuring out the rules of engagement is even harder considering the law went into effect only a month ago, but Rawlins said he feels supported by his school and the district in trying to untangle the mess.

Now, when students send emails to teachers before classes start explaining their name and pronouns — and when that name doesn’t match the legal name on the class roster — they’re potentially incriminating themselves, Rawlins said. Before classes began August 15, one student sent an email to eight teachers alerting them to his name and pronouns — and made it clear that his family does not support addressing him that way, Rawlins said.

“Well, now what do we do? Because a kid has sent through a public school email system, now it’s a matter of public record that they want to go by these pronouns, they want to use this name. But they don’t want parents to find out,” he said.

Those scenarios are prompting teachers like Rawlins to ask their students if they are sure that they want to follow through with what they’re asking for — to be acknowledged and affirmed in their gender identity — and if they understand what Florida’s law says.

“It’s just tough,” he said. “For some of them, it’s fine, because they’ve got supportive families. For those kids, things are actually going pretty well this year. … But for those who don’t have a supportive household, it’s tough right now.”

In Texas, the legislative body is out of session after introducing more than 40 bills targeting transgender youth last year, out of which only one passed into law. And at the local level, efforts to restrict education are making headway. A school district in Grapevine, Texas, recently voted to require students to use bathrooms dictated by their sex assigned at birth and to encourage teachers to ignore students’ requests on using their current pronouns, the Texas Tribune reports.

For one 16-year-old trans girl with a supportive family who’s starting her junior year in Austin’s Independent School District, this year marks feeling more confident — in her sense of style, in having more friends and being more able to express herself after transitioning during pandemic school shutdowns. She asked to be anonymous due to Texas’ attempts to criminalize families that obtain gender-affirming care for trans minors.

She feels safe at her school largely due to supportive teachers and friends — and because not many of the people she knows at school know or care that she is transgender. This year, teachers asked students to fill out a Google doc with their pronouns and preferred name — and if those are the same at home and at school. That helped her feel at ease.

“I am worried about other kids who aren’t as well off or as privileged as me,” she said. “If there’s a kid and they’re trans, but they’re not out to their parents or they haven’t had that gender marker change or the name change … it’s hard to go through school while also being validated and just respected.”

Jason Stanford, spokesperson for the Austin school district, said that the district aims to be welcoming for LGBTQ+ and trans students, who should be able to use bathrooms according to their gender identity, or single-stall facilities if that student is worried about bullying.

“If I have to choose between an angry parent and making a kid feel safe, me and everyone I work with is going to make the same choice,” he said. “I think too often in these discussions, we center the emotional security of adults at the expense of children.”

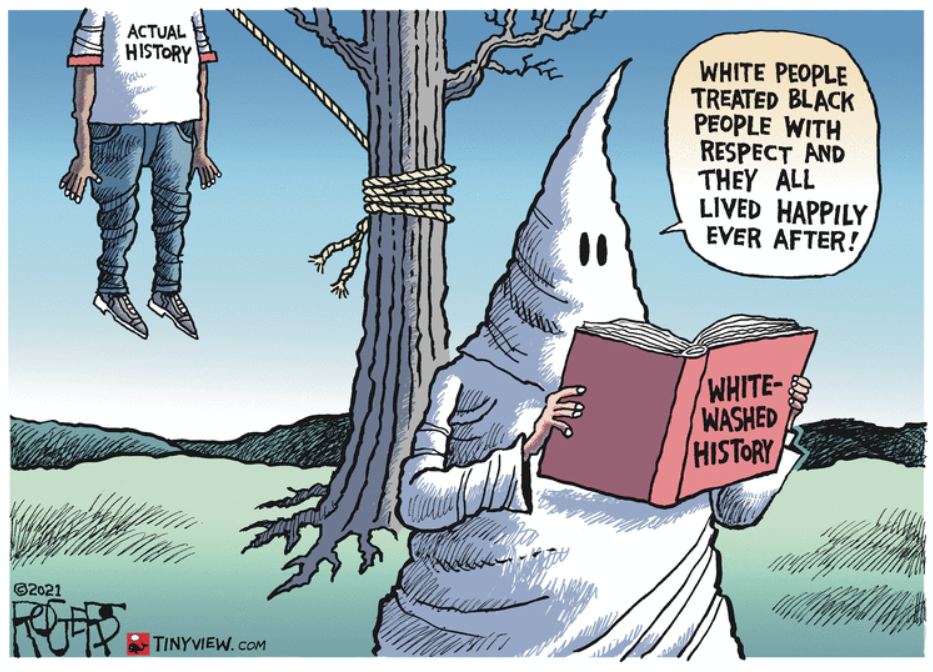

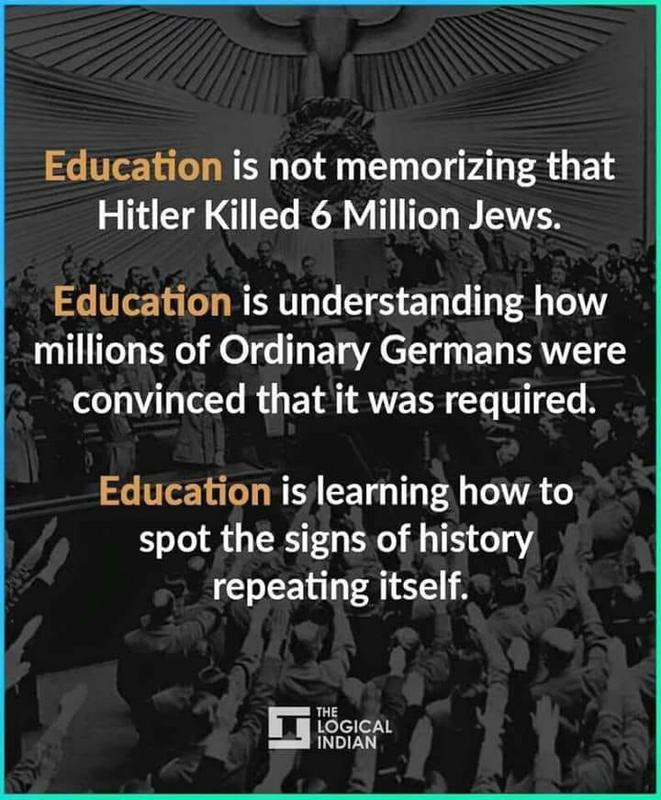

THE EDUCATION OF A RACIST!!!

IT STARTS AT HOME AND CONTINUES IN AMERICA'S PUBLIC SCHOOL!

We Found the Textbooks of Senators Who Oppose The 1619 Project and Suddenly Everything Makes Sense

ByMichael Harriot - the root

5/06/21

...The Root decided to see what some of the signatories to Mitch McConnell’s Strawberry Letter knew about slavery and Black history. We dug through state curriculum standards, yearbooks and spoke with teachers to see which interpretation of history the white tears-spewing politicians learned when they were in elementary and high school. In doing so, there are certain things we realized:

Knowing this, we dug through bios, school archives and academic resources to find out how these GOP legislators gained their knowledge of America’s past. In most cases, we were able to find the exact textbook each legislator’s school district used for one of the state or American history courses. In other cases, we were able to find contemporaneous descriptions of the textbooks from academic journals or reports. To our surprise, most received a well-rounded education on the history of Black people in America.

Just kidding. They all learned variations of the same white lies. And, apparently, they’d like to keep it that way.

Here’s what we found.

Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.)

What she said: “The 1619 Project is nothing more than left-wing propaganda. Tennesseans don’t want it in our schools. We want our children to learn about our nation’s history.”

What she read: Although she represents Tennessee, Marsha Blackburn attended elementary and high school in Laurel, Miss. In 1959, the year Sen. Marsha Blackburn would have entered kindergarten in Mississippi, the state legislature handed control of choosing textbooks to Gov. Ross Barnett. At the request of the Mississippi State Society of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), the state had already mandated a ninth-grade course in Mississippi history, which means Blackburn learned the history of her state from John K. Bettersworth’s textbook Mississippi: a History.

The New York Times wrote in 1975 that Bettersworth’s catalogs “treat blacks of old as complacent darkies or as a problem to whites.” When The Root reviewed the text, we noticed that the entire history of the 250-year institution of slavery was reduced to five pages. Bettersworth’s book was based on UDC propaganda that taught children that the slave master treated his slaves “as his own,” but noted that most of the human chattel were so lazy that “it took two to help; one to do nothing.” However, Bettersworth was sure to point out the kindness of the masters who educated the enslaved “as they taught their own children.”

Mississippi: A History also treats the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education case as a travesty, insisting that Mississippians were largely satisfied with segregated schools. “Incidents had been extremely rare,” it explained. “[F]or by and large, each race—its parents, its pupils and their teachers, had found it advantageous to remain in an ‘equal but separate’ status.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy play an outsized role in the way we learn history. Formed in the late 19th century, the group is not only responsible for most of the Confederate monuments in America but perhaps their biggest memorial to the white supremacist utopia known as the Confederacy is how they instilled their beliefs in schools across America. By turning Southern housewives into lobbyists for the Lost Cause ideology, they transformed history into a fictional version of the past, complete with happy slaves and brave, honorable white men who just wanted low taxes. By the early 1920s, they had become so powerful that a history book didn’t stand a chance of being approved if it contained a negative portrayal of the Antebellum South or the Civil War.

Blackburn’s alma mater, Northeast Jones, integrated in the fall of 1970, the year after Blackburn graduated.

---

Ted Cruz (R-Texas)

What he said: “Why should the false revisionist history not be used as the basis of K-12 education across the nation? Not because of ‘cancel culture,’ which you support. But because it wrong & deliberately deceptive.”

What he read: Because Ted Cruz attended private Christian academies for his entire educational career, we could not verify the specific book used by Cruz’s elementary school to teach Texas history. However, his Advanced Placement U.S. History class—required in Second Baptist High School’s curriculum—likely used the eighth edition of The American Pageant, which contained most of the same passages outlined earlier. As late as 2016, the text still contained racist themes, according to CBS.

If Second Baptist High School adhered to the standards of the Texas Department of Education, we can surmise that Cruz had to learn speeches from Jefferson Davis, but not that slavery caused the Civil War, which wasn’t taught in Texas schools until 2018. Texas’ social studies curriculum “deemphasized slavery, questioned New Deal entitlements and mandated study of the “optimism’ of ‘thankful’ immigrants,” before 2010, according to the Texas Tribune. The state also believed Harriet Tubman was too sensitive a subject for third-graders but taught that slavery was the “third-most-influential cause of the war.”

Before graduating in 1988, Cruz was a member of the ultra-libertarian Constitutional Corroborators, the high school junior varsity team for the Free Enterprise Institute, which still promotes the belief that the Civil War was mostly about tariffs and economics. We also know that Cruz’s alma mater was affiliated with the pro-Confederate Southern Baptist Convention, which finally reckoned with its racist past in 2018. The institution seceded from the larger organization in 1845 over slavery.

---

Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.)

What he said: “I think America is a unique experiment that stood the test of time. We’re better today than we were 10 years ago and, hopefully, 10 years from now, we’ll be better. Striving to be better is always the goal. But, no, I do not believe my state, I do not believe my nation, is systematically racist.”

What he read: Although Brown v. Board of Education officially outlawed segregation in 1955, Lindsey Graham’s school district in Pickens County, S.C., didn’t desegregate until 1970. So it’s understandable why he learned history from The History of South Carolina, published from 1840 until 1970 by three generations of descendants of pro-Confederate William Simms. While Simms’ early versions opined about the “irresponsible, uneducated, unmoral and, in many cases brutish Africans,” Graham likely used the 1958 edition where Mary C. Simms Oliphant, Simm’s granddaughter, had a much more progressive view.

“Most masters treated their slaves kindly,” wrote Oliphant. “Africans were brought from a worse life to a better one. As slaves, they were trained in the ways of civilization. Above all, the landowners argued, the slaves were given the opportunity to become Christians in a Christian land, instead of remaining heathen in a savage country.”[...]

READ MORE

- There is no one Social Studies curriculum: Most states’ departments of educations create a K-12 social studies curriculum that sets a minimum standard for what students should learn by a certain grade (Here is Georgia’s). The rest is usually left up to the districts, schools and even the teachers.

- There are two histories: As someone who was homeschooled, this was a revelation to me. The majority of K-12 students cycle through two levels of social studies. The basics of geography, civics and history are usually taught in elementary and middle school. Students learn another, more detailed history and civics curriculum in high school that usually includes separate courses for civics/government, world history, and American history.

- But really, there are three histories: Many states mandate a “state history” course, usually from a limited selection of one or two state-approved textbooks. In some cases, the state course totally contradicts what the students learn in American history classes.

- Sometimes there are four histories. There are some states where students take two different state history courses—one elementary level class and one high school level class.

- ...Or six histories: Take Georgia, for instance. In elementary school, students learn the basics of American history and state history. In middle school, they take world history and another year of state history. In high school, they do it over again, with mandatory courses in world history and U.S. history. However, in Georgia, and in most states, students use textbooks from different publishers and authors, many of which tell completely contradictory versions of the same stories.

- But no Black history: Aside from cursory mentions of the Civil War, Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement, most state educational curriculums don’t specify how much history should be dedicated to Black history. In Georgia, students have courses on Native American history, Latin American and Caribbean culture, a course that combines African and Asian geography, but nothing specifically on Black history.

Knowing this, we dug through bios, school archives and academic resources to find out how these GOP legislators gained their knowledge of America’s past. In most cases, we were able to find the exact textbook each legislator’s school district used for one of the state or American history courses. In other cases, we were able to find contemporaneous descriptions of the textbooks from academic journals or reports. To our surprise, most received a well-rounded education on the history of Black people in America.

Just kidding. They all learned variations of the same white lies. And, apparently, they’d like to keep it that way.

Here’s what we found.

Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.)

What she said: “The 1619 Project is nothing more than left-wing propaganda. Tennesseans don’t want it in our schools. We want our children to learn about our nation’s history.”

What she read: Although she represents Tennessee, Marsha Blackburn attended elementary and high school in Laurel, Miss. In 1959, the year Sen. Marsha Blackburn would have entered kindergarten in Mississippi, the state legislature handed control of choosing textbooks to Gov. Ross Barnett. At the request of the Mississippi State Society of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), the state had already mandated a ninth-grade course in Mississippi history, which means Blackburn learned the history of her state from John K. Bettersworth’s textbook Mississippi: a History.

The New York Times wrote in 1975 that Bettersworth’s catalogs “treat blacks of old as complacent darkies or as a problem to whites.” When The Root reviewed the text, we noticed that the entire history of the 250-year institution of slavery was reduced to five pages. Bettersworth’s book was based on UDC propaganda that taught children that the slave master treated his slaves “as his own,” but noted that most of the human chattel were so lazy that “it took two to help; one to do nothing.” However, Bettersworth was sure to point out the kindness of the masters who educated the enslaved “as they taught their own children.”

Mississippi: A History also treats the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education case as a travesty, insisting that Mississippians were largely satisfied with segregated schools. “Incidents had been extremely rare,” it explained. “[F]or by and large, each race—its parents, its pupils and their teachers, had found it advantageous to remain in an ‘equal but separate’ status.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy play an outsized role in the way we learn history. Formed in the late 19th century, the group is not only responsible for most of the Confederate monuments in America but perhaps their biggest memorial to the white supremacist utopia known as the Confederacy is how they instilled their beliefs in schools across America. By turning Southern housewives into lobbyists for the Lost Cause ideology, they transformed history into a fictional version of the past, complete with happy slaves and brave, honorable white men who just wanted low taxes. By the early 1920s, they had become so powerful that a history book didn’t stand a chance of being approved if it contained a negative portrayal of the Antebellum South or the Civil War.

Blackburn’s alma mater, Northeast Jones, integrated in the fall of 1970, the year after Blackburn graduated.

---

Ted Cruz (R-Texas)

What he said: “Why should the false revisionist history not be used as the basis of K-12 education across the nation? Not because of ‘cancel culture,’ which you support. But because it wrong & deliberately deceptive.”

What he read: Because Ted Cruz attended private Christian academies for his entire educational career, we could not verify the specific book used by Cruz’s elementary school to teach Texas history. However, his Advanced Placement U.S. History class—required in Second Baptist High School’s curriculum—likely used the eighth edition of The American Pageant, which contained most of the same passages outlined earlier. As late as 2016, the text still contained racist themes, according to CBS.

If Second Baptist High School adhered to the standards of the Texas Department of Education, we can surmise that Cruz had to learn speeches from Jefferson Davis, but not that slavery caused the Civil War, which wasn’t taught in Texas schools until 2018. Texas’ social studies curriculum “deemphasized slavery, questioned New Deal entitlements and mandated study of the “optimism’ of ‘thankful’ immigrants,” before 2010, according to the Texas Tribune. The state also believed Harriet Tubman was too sensitive a subject for third-graders but taught that slavery was the “third-most-influential cause of the war.”

Before graduating in 1988, Cruz was a member of the ultra-libertarian Constitutional Corroborators, the high school junior varsity team for the Free Enterprise Institute, which still promotes the belief that the Civil War was mostly about tariffs and economics. We also know that Cruz’s alma mater was affiliated with the pro-Confederate Southern Baptist Convention, which finally reckoned with its racist past in 2018. The institution seceded from the larger organization in 1845 over slavery.

---

Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.)

What he said: “I think America is a unique experiment that stood the test of time. We’re better today than we were 10 years ago and, hopefully, 10 years from now, we’ll be better. Striving to be better is always the goal. But, no, I do not believe my state, I do not believe my nation, is systematically racist.”

What he read: Although Brown v. Board of Education officially outlawed segregation in 1955, Lindsey Graham’s school district in Pickens County, S.C., didn’t desegregate until 1970. So it’s understandable why he learned history from The History of South Carolina, published from 1840 until 1970 by three generations of descendants of pro-Confederate William Simms. While Simms’ early versions opined about the “irresponsible, uneducated, unmoral and, in many cases brutish Africans,” Graham likely used the 1958 edition where Mary C. Simms Oliphant, Simm’s granddaughter, had a much more progressive view.

“Most masters treated their slaves kindly,” wrote Oliphant. “Africans were brought from a worse life to a better one. As slaves, they were trained in the ways of civilization. Above all, the landowners argued, the slaves were given the opportunity to become Christians in a Christian land, instead of remaining heathen in a savage country.”[...]

READ MORE

Low Literacy Levels Among U.S. Adults Could Be Costing The Economy $2.2 Trillion A Year

Michael T. Nietzel - FORBES

Sep 9, 2020

A new study by Gallup on behalf of the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy finds that low levels of adult literacy could be costing the U.S. as much $2.2 trillion a year.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, 54% of U.S. adults 16-74 years old - about 130 million people - lack proficiency in literacy, reading below the equivalent of a sixth-grade level. That’s a shocking number for several reasons, and its dollars and cents implications are enormous because literacy is correlated with several important outcomes such as personal income, employment levels, health, and overall economic growth.

Commenting on the significance of the study, British A. Robinson, president and CEO of the Barbara Bush Foundation, said, “America’s low literacy crisis is largely ignored, historically underfunded and woefully under-researched, despite being one of the great solvable problems of our time. We’re proud to enrich the collective knowledge base with this first-of-its-kind study, documenting literacy’s key role in equity and economic mobility in families, communities and our nation as a whole.”

The new research by Gallup attempts to estimate the gains in GDP that could result from improving adult literacy rates for the nation as a whole as well as in the individual states and major metropolitan areas. Here’s the basic methodology of the study, entitled “Assessing the Economic Gains of Eradicating Illiteracy Nationally and Regionally in the United States,” under the direction of lead author Dr. Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

Rothwell relied on an international assessment of adult skills called the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) that classifies literacy into several levels. The Department of Education used those results to create and publish estimated literacy levels for every U.S. county.

Adults who scored below Level 3 for literacy on the PIAAC were defined as at least partially illiterate. Adults below or at Level 1 may struggle to understand texts beyond filling out basic forms, and they find it difficult to make inferences from written material. Adults at Level 2 can read well enough to evaluate product reviews and perform other tasks requiring comparisons and simple inferences, but they’re unlikely to correctly evaluate the reliability of texts or draw sophisticated inferences. Adults at Level 3 and above were considered fully literate. They’re able to evaluate sources, as well as infer sophisticated meaning and complex ideas from written sources.

To estimate national income gains, the study compared the incomes of people with different levels of literacy. Since literacy varies by age, race, gender, and other demographic characteristics, the study adjusted for these factors in order to better determine how income rises with literacy for individuals who are otherwise alike. That allowed it to estimate the average income gains that could be expected for an individual moving from below-proficiency in literacy to minimal proficiency.

A similar approach was used at the county and state levels, using newly created literacy estimates from the U.S. Department of Education and estimated income differences based on data from the Census Bureau.

“This study translates into dollars and cents what the literacy field has known for decades: low literacy prevents millions of Americans from fully participating in our society and our economy as parents, workers and citizens,” said Robinson. “It lies at the core of multigenerational cycles of poverty, poor health, and low educational attainment, contributing to the enormous equity gap that exists in our country.”

She continued, “This research clearly shows that investing in adult literacy is absolutely critical to the strength of our nation, now and for generations to come. It proves that what Barbara Bush said more than 30 years ago is still true today: ‘Literacy is everyone’s business. Period.’”

Key Findings

Income is strongly related to literacy.

The average annual income of adults who are at the minimum proficiency level for literacy (Level 3) is nearly $63,000, significantly higher than the average of roughly $48,000 earned by adults who are just below proficiency (Level 2) and much higher than those at the lowest levels of literacy (Levels 0 and 1), who earn just over $34,000 on average.

Because individuals with varying levels of literacy different in several other ways, such as age, gender, urbanicity, race, ethnicity, and parental education, the authors controlled for those differences and found that while the large income differences between people with different literacy skills shrank, they were still quite large:

Eradicating illiteracy would yield huge economic benefits.

If all U.S. adults were able to move up to at least Level 3 of literacy proficiency, it would generate an additional $2.2 trillion in annual income for the country, equal to 10% of the gross domestic product.

Areas with the lowest levels of literacy would see the largest gains.

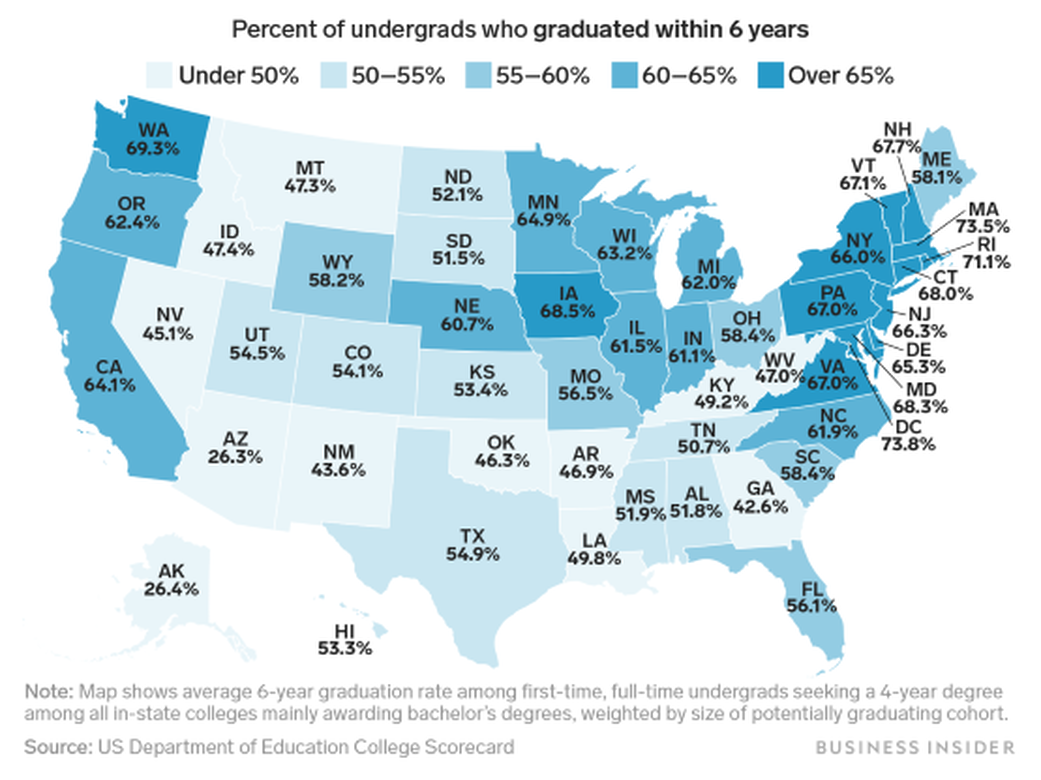

States that have a disproportionate share of adults with low levels of literacy would gain the most economically from increasing literacy skills. For example, in Alabama, an estimated 61% of adults fall below Level 3 literacy on the PIACC. If they could be moved to Level 3, the gains would be 15.6% of Alabama’s GDP.

By contrast, gains from eradicating illiteracy would be relatively small - 5% of local GNP - in Washington, D.C., where 47% of the population is nonproficient. In North Dakota, where there’re relatively high-paying opportunities for less educated workers, the individual gains from literacy are smaller. North Dakota also has low rates of nonproficiency (45%). These two factors in combination explain why North Dakota would see income gains of only 3.9% of its GDP.

Big economic gains would be achieved in large metropolitan areas.

The study also found that the nation’s largest metropolitan areas – including New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago and Dallas – would all gain at or just above 10% of their GDP by bringing all adults to a sixth grade reading level

_____________

“The U.S. confronts a long-standing challenge of high-income inequality, with strikingly large gaps in wealth and income between people of different races,” said lead author, Jonathan Rothwell. “On top of these long-term challenges, the Covid-19 pandemic has weakened the economy and overlapped with a robust movement addressing racial injustice. Eradicating literacy would not solve every problem, but it would help make substantial progress in reducing inequality in the long-term and give a much-needed boost to local and regional economies throughout the country.”

“Eradicating literacy would be enormously valuable under any circumstances,” Rothwell continued. “Given the current economic and health challenges, there is even more at stake in ensuring that everyone can fully participate in society.”

According to the U.S. Department of Education, 54% of U.S. adults 16-74 years old - about 130 million people - lack proficiency in literacy, reading below the equivalent of a sixth-grade level. That’s a shocking number for several reasons, and its dollars and cents implications are enormous because literacy is correlated with several important outcomes such as personal income, employment levels, health, and overall economic growth.

Commenting on the significance of the study, British A. Robinson, president and CEO of the Barbara Bush Foundation, said, “America’s low literacy crisis is largely ignored, historically underfunded and woefully under-researched, despite being one of the great solvable problems of our time. We’re proud to enrich the collective knowledge base with this first-of-its-kind study, documenting literacy’s key role in equity and economic mobility in families, communities and our nation as a whole.”

The new research by Gallup attempts to estimate the gains in GDP that could result from improving adult literacy rates for the nation as a whole as well as in the individual states and major metropolitan areas. Here’s the basic methodology of the study, entitled “Assessing the Economic Gains of Eradicating Illiteracy Nationally and Regionally in the United States,” under the direction of lead author Dr. Jonathan Rothwell, Gallup’s principal economist.

Rothwell relied on an international assessment of adult skills called the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) that classifies literacy into several levels. The Department of Education used those results to create and publish estimated literacy levels for every U.S. county.

Adults who scored below Level 3 for literacy on the PIAAC were defined as at least partially illiterate. Adults below or at Level 1 may struggle to understand texts beyond filling out basic forms, and they find it difficult to make inferences from written material. Adults at Level 2 can read well enough to evaluate product reviews and perform other tasks requiring comparisons and simple inferences, but they’re unlikely to correctly evaluate the reliability of texts or draw sophisticated inferences. Adults at Level 3 and above were considered fully literate. They’re able to evaluate sources, as well as infer sophisticated meaning and complex ideas from written sources.

To estimate national income gains, the study compared the incomes of people with different levels of literacy. Since literacy varies by age, race, gender, and other demographic characteristics, the study adjusted for these factors in order to better determine how income rises with literacy for individuals who are otherwise alike. That allowed it to estimate the average income gains that could be expected for an individual moving from below-proficiency in literacy to minimal proficiency.

A similar approach was used at the county and state levels, using newly created literacy estimates from the U.S. Department of Education and estimated income differences based on data from the Census Bureau.

“This study translates into dollars and cents what the literacy field has known for decades: low literacy prevents millions of Americans from fully participating in our society and our economy as parents, workers and citizens,” said Robinson. “It lies at the core of multigenerational cycles of poverty, poor health, and low educational attainment, contributing to the enormous equity gap that exists in our country.”

She continued, “This research clearly shows that investing in adult literacy is absolutely critical to the strength of our nation, now and for generations to come. It proves that what Barbara Bush said more than 30 years ago is still true today: ‘Literacy is everyone’s business. Period.’”

Key Findings

Income is strongly related to literacy.

The average annual income of adults who are at the minimum proficiency level for literacy (Level 3) is nearly $63,000, significantly higher than the average of roughly $48,000 earned by adults who are just below proficiency (Level 2) and much higher than those at the lowest levels of literacy (Levels 0 and 1), who earn just over $34,000 on average.