first americans

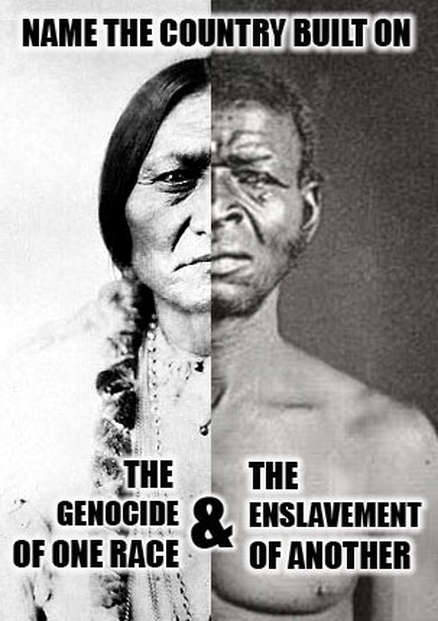

The American Indian Holocaust, known as the “500 year war” and the “World’s Longest Holocaust In The History Of Mankind And Loss Of Human Lives.”

october 2023

*current events*

Life Expectancy for Indigenous Americans Drops by 6.6 Years

BY Chris Walker, Truthout

PUBLISHED September 9, 2022

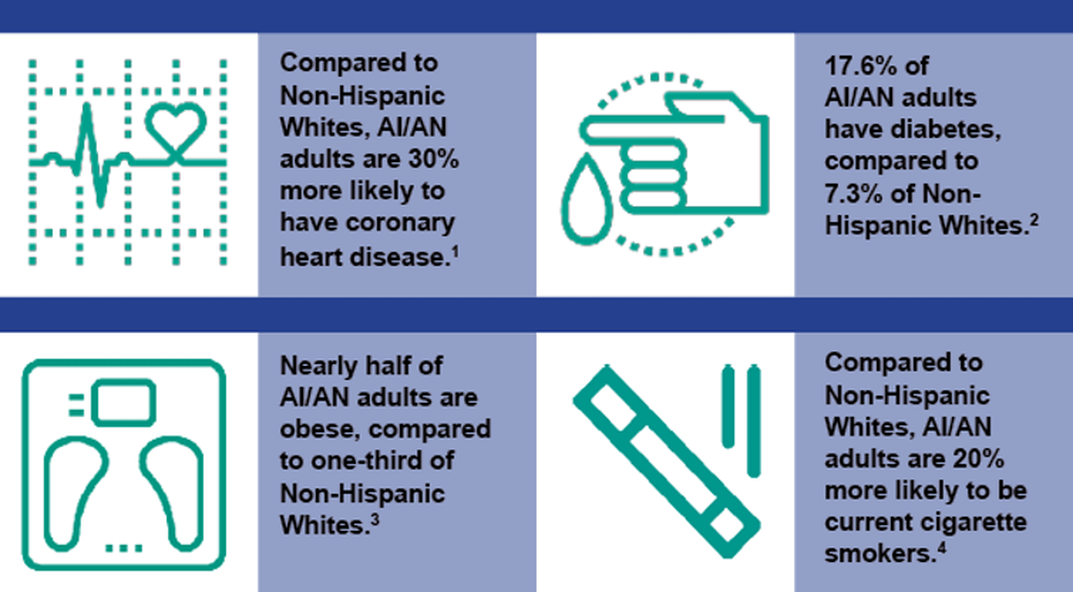

Life expectancy declined for Americans overall over the past two years due primarily to the coronavirus pandemic. But for Indigenous Americans, the decline was far worse, exacerbated by conditions and inequities that existed prior to the virus’s emergence.

Native Americans and Alaska Natives saw their life expectancy rates drop by 6.6 years over the past two years. Their life expectancies — which were already low compared to the rest of the U.S. population before the pandemic began — fell to 65 years old in 2021, according to figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts say there isn’t a singular cause for the dramatic decline, which was more than twice the decline for Americans overall (a 2.75 years drop over the two-year period).

The suffering is inextricably bound to a long history of poverty, inadequate access to health care, poor infrastructure and crowded housing, much of it the legacy of broken government promises and centuries of bigotry,” The New York Times reported late last month.

Researchers were initially surprised at the precipitous drop.

“When I saw a 6.6 year decline over two years, my jaw dropped…I made my staff re-run the numbers to make sure,” said Robert Anderson, chief of the mortality statistics branch of the National Center for Health Statistics.

But for Indigenous people throughout the country, the numbers — though horrifying — weren’t shocking.

“This is simply what happens biologically to populations that are chronically and profoundly stressed and deprived of resources,” said Ann Bullock, former director of diabetes treatment at federal Indian Health Services, and a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, in an interview with The Times.

In fact, it’s highly probable that the decline is even worse than what researchers have discovered.

“It is not uncommon for a Native person to be identified as Native on their birth certificate but listed differently on their death certificates, usually listed as white,” noted Jennie R. Joe, a professor emerita at the University of Arizona’s Wassaja Carlos Montezuma Center for Native American Health. “It is therefore safe to say that the current life expectancy reported for Native Americans is probably a case of undercounting.”

“Discrimination is deadly,” noted Cindy Blackstock, a Canadian Gitxsan activist for child welfare and the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. “With unequal public services and colonial traumas, COVID took a shocking toll” on Indigenous populations, she said.

Notably, life expectancy rates were not uniform across Native American communities, Spiro M. Manson, director of the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado, told Boise State Public Radio News.

“These rates of lowered life expectancy vary enormously by region, and they vary enormously by tribes,” said Manson, who is Pembina Chippewa.

But it’s clear that institutional racism and the ongoing effects of colonialism played a role, experts say.

“I was perusing the recent CDC Vital Statistics report on life expectancy, and one thing struck me this time as a clear indicator of structural racism: On average, white people live *a whole decade* longer than Indigenous people,” said Joseph M. Pierce, a Cherokee Nation Citizen and associate professor at Stony Brook University.

Native Americans and Alaska Natives saw their life expectancy rates drop by 6.6 years over the past two years. Their life expectancies — which were already low compared to the rest of the U.S. population before the pandemic began — fell to 65 years old in 2021, according to figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts say there isn’t a singular cause for the dramatic decline, which was more than twice the decline for Americans overall (a 2.75 years drop over the two-year period).

The suffering is inextricably bound to a long history of poverty, inadequate access to health care, poor infrastructure and crowded housing, much of it the legacy of broken government promises and centuries of bigotry,” The New York Times reported late last month.

Researchers were initially surprised at the precipitous drop.

“When I saw a 6.6 year decline over two years, my jaw dropped…I made my staff re-run the numbers to make sure,” said Robert Anderson, chief of the mortality statistics branch of the National Center for Health Statistics.

But for Indigenous people throughout the country, the numbers — though horrifying — weren’t shocking.

“This is simply what happens biologically to populations that are chronically and profoundly stressed and deprived of resources,” said Ann Bullock, former director of diabetes treatment at federal Indian Health Services, and a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, in an interview with The Times.

In fact, it’s highly probable that the decline is even worse than what researchers have discovered.

“It is not uncommon for a Native person to be identified as Native on their birth certificate but listed differently on their death certificates, usually listed as white,” noted Jennie R. Joe, a professor emerita at the University of Arizona’s Wassaja Carlos Montezuma Center for Native American Health. “It is therefore safe to say that the current life expectancy reported for Native Americans is probably a case of undercounting.”

“Discrimination is deadly,” noted Cindy Blackstock, a Canadian Gitxsan activist for child welfare and the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. “With unequal public services and colonial traumas, COVID took a shocking toll” on Indigenous populations, she said.

Notably, life expectancy rates were not uniform across Native American communities, Spiro M. Manson, director of the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado, told Boise State Public Radio News.

“These rates of lowered life expectancy vary enormously by region, and they vary enormously by tribes,” said Manson, who is Pembina Chippewa.

But it’s clear that institutional racism and the ongoing effects of colonialism played a role, experts say.

“I was perusing the recent CDC Vital Statistics report on life expectancy, and one thing struck me this time as a clear indicator of structural racism: On average, white people live *a whole decade* longer than Indigenous people,” said Joseph M. Pierce, a Cherokee Nation Citizen and associate professor at Stony Brook University.

dakota war

Ruth H. Hopkins, B.S., M.S., J.D. - thread reader

12/26/2020

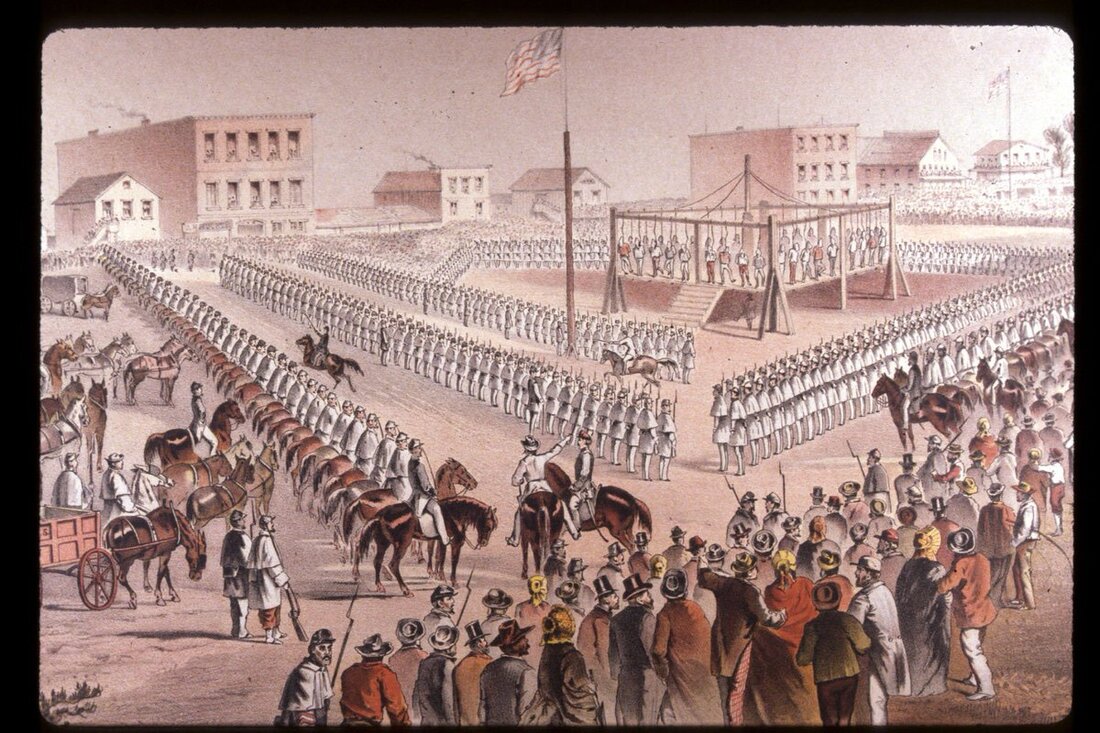

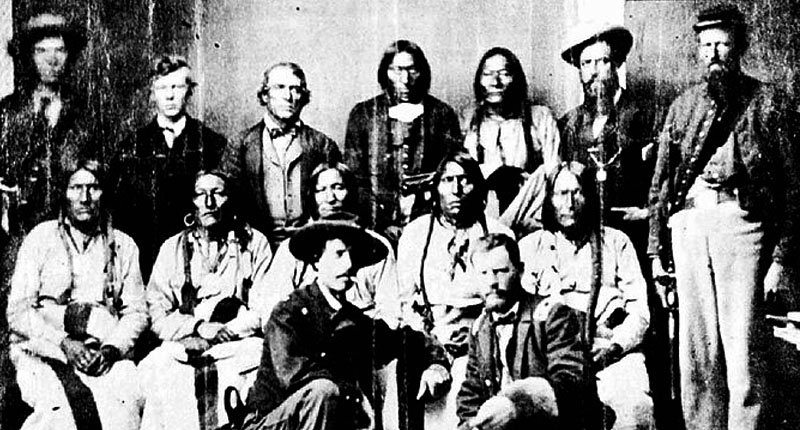

158 years ago today, the largest mass execution in U.S. history took place under the orders of Abraham Lincoln. On Dec 26, 1862, the day after Christmas, 38 Dakota warriors were hanged in Mankato, MN. #Dakota38

The execution happened at the culmination of the Dakota War, which started because the U.S. government unilaterally breached 2 treaties it made with the Dakota. The Dakota gave up land in exchange for $ and food. They weren't given neither & were starving.

U.S. Congress purposely breached treaty by omitting an article in it that set aside lands for Dakota, without telling them. Then the agent charged with providing Dakota with rations said, “Let them eat grass or their own dung,” while Dakota children were dying of starvation.

The Dakota were still abiding by Treaty Law & couldn’t go hunting as they would have before. The war began when some Dakota stole eggs to eat and fighting broke out. Andrew Myrick, the dung-loving agent, was among the first to die. He was found with grass in his mouth. #Dakota38

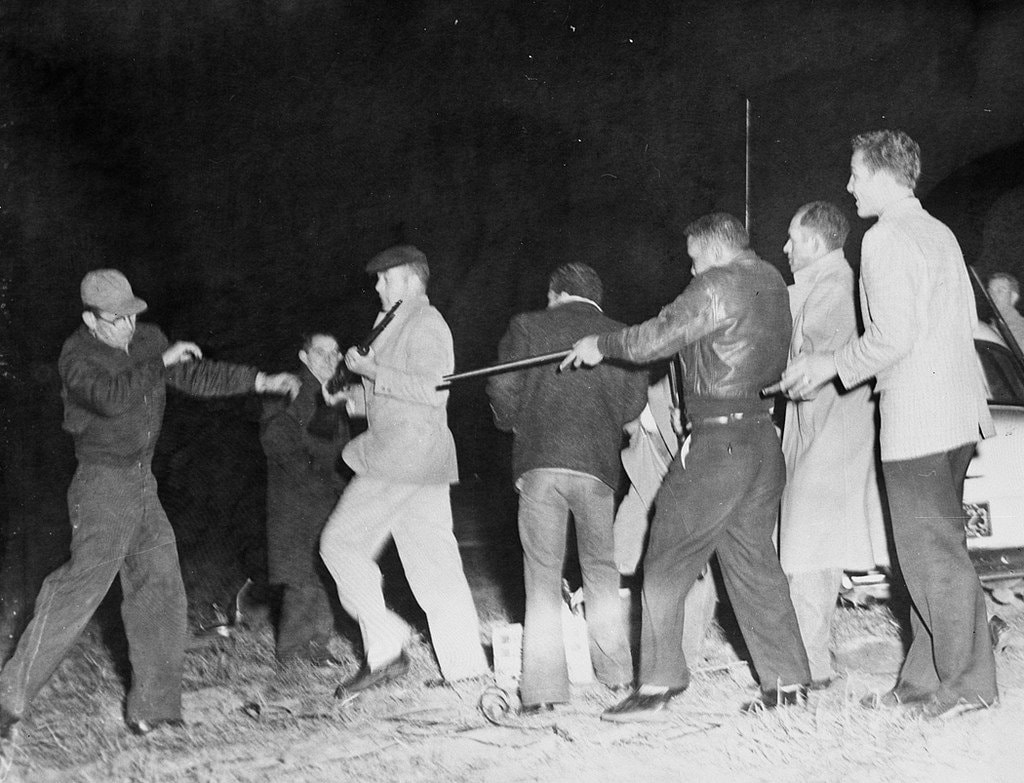

The warriors didn’t receive due process. ‘Trials’ were held in English, a foreign language— they had no legal representation and argument about broken Treaties wasn’t allowed. 38 men, many innocent, were hanged anyway, on a custom made scaffold, in front of a bloodthirsty mob.

---

Dakota women and children were forced to watch the hanging. A Dakota infant was snatched from the arms of their mother by the settler mob and murdered on the spot during the execution. If Dakota women and children defended themselves they could’ve also be killed. #Dakota38

Around 1700 Dakota, mostly women and children, were imprisoned at Fort Snelling. Disease & death were rampant. They buried children every day. This is Chief Little Crow’s wife and children at Fort Snelling. He was later killed by settlers, his body grossly mutilated. #Dakota38

Before the hanging, the warriors prayed with the canupa (pipe) and sang songs. Among them were underaged minors and the mentally disabled. One of them was also a white man who had been adopted and raised by the Dakota. During the execution, some were holding hands. #Dakota38

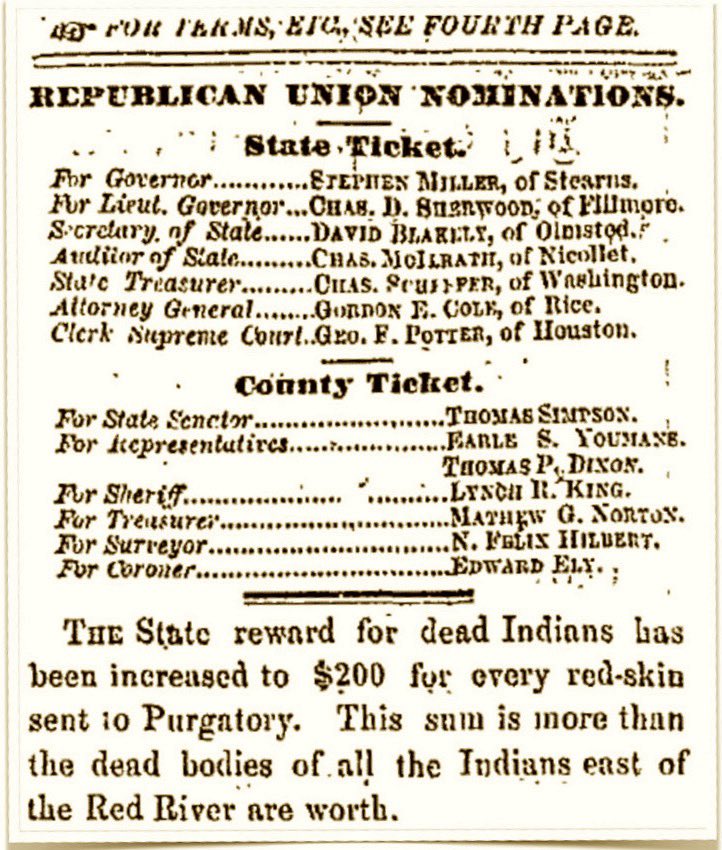

After the hanging, Dakota were exiled from their Minnesota homelands. The state put out a bounty on the scalps of every Dakota man, woman and child.

The execution happened at the culmination of the Dakota War, which started because the U.S. government unilaterally breached 2 treaties it made with the Dakota. The Dakota gave up land in exchange for $ and food. They weren't given neither & were starving.

U.S. Congress purposely breached treaty by omitting an article in it that set aside lands for Dakota, without telling them. Then the agent charged with providing Dakota with rations said, “Let them eat grass or their own dung,” while Dakota children were dying of starvation.

The Dakota were still abiding by Treaty Law & couldn’t go hunting as they would have before. The war began when some Dakota stole eggs to eat and fighting broke out. Andrew Myrick, the dung-loving agent, was among the first to die. He was found with grass in his mouth. #Dakota38

The warriors didn’t receive due process. ‘Trials’ were held in English, a foreign language— they had no legal representation and argument about broken Treaties wasn’t allowed. 38 men, many innocent, were hanged anyway, on a custom made scaffold, in front of a bloodthirsty mob.

---

Dakota women and children were forced to watch the hanging. A Dakota infant was snatched from the arms of their mother by the settler mob and murdered on the spot during the execution. If Dakota women and children defended themselves they could’ve also be killed. #Dakota38

Around 1700 Dakota, mostly women and children, were imprisoned at Fort Snelling. Disease & death were rampant. They buried children every day. This is Chief Little Crow’s wife and children at Fort Snelling. He was later killed by settlers, his body grossly mutilated. #Dakota38

Before the hanging, the warriors prayed with the canupa (pipe) and sang songs. Among them were underaged minors and the mentally disabled. One of them was also a white man who had been adopted and raised by the Dakota. During the execution, some were holding hands. #Dakota38

After the hanging, Dakota were exiled from their Minnesota homelands. The state put out a bounty on the scalps of every Dakota man, woman and child.

OP-ED RACIAL JUSTICE

The Catholic Church Is Responding to Indigenous Protest With Exorcisms

BY Charles Sepulveda, Truthout

PUBLISHED November 26, 2020

On this day, Indigenous activists in New England and beyond are observing a National Day of Mourning to mark the theft of land, cultural assault and genocide that followed after the anchoring of the Mayflower on Wampanoag land in 1620 — a genocide that is erased within conventional “Thanksgiving Day” narratives.

The acts of mourning and resistance taking place today build on the energy of Indigenous People’s Day 2020, which was also a day of uprising. On October 11, 2020, also called “Indigenous People’s Day of Rage,” participants around the country took part in actions such as de-monumenting — the toppling of statues of individuals dedicated to racial nation-building.

In response to Indigenous-led efforts that demanded land back and the toppling of statues, Catholic Church leaders in Oregon and California deemed it necessary to perform exorcisms, thereby casting Indigenous protest as demonic.

The toppled statues included President Abraham Lincoln, President Theodore Roosevelt and Father Junípero Serra, who founded California’s mission system (1769-1834) and was canonized into sainthood by the Catholic Church and Pope Francis in 2015.

What do these leaders whose statues were toppled have in common? They perpetrated and promoted devastating violence against Native peoples.

Abraham Lincoln was responsible for the largest mass execution in United States history when 38 Dakota were hanged in 1862 after being found guilty for their involvement in what is known as the “Minnesota Uprising.”

Theodore Roosevelt gave a speech in 1886 in New York that would have made today’s white supremacists blush when he declared: “I don’t go as far as to think that the only good Indian is the dead Indian, but I believe nine out of every ten are…” This was not his only foray in promoting racial genocide.

Junípero Serra is known for having committed cruel punishments against the Indians of California and enslaved them as part of Spain’s genocidal conquest.

Last month, “Land Back” and “Dakota 38” were scrawled on the base of the now-toppled Lincoln statue in Portland, Oregon. The political statements and demands for land return reveal a Native decolonial spirit based in resistance continuing through multiple generations.

The “Indigenous People’s Day of Rage” came after months of protests in Portland in support of Black Lives Matter. The resistance enacted in Portland coincides with demands for both abolition (the end of racialized policing and imprisonment) and decolonization (the return of land and regeneration of life outside of colonialism). Both of these notions encompass a multifaceted imagining of life beyond white supremacy.

In San Rafael, California, Native activists gathered at the Spanish mission that had been the site of California Indian enslavement. Activists, who included members of the Coast Miwok of Marin, first poured red paint on the statue of Serra and then pulled it down with ropes, while other protesters held signs that read: “Land Back Now” and “We Stand on Unceded Land – Decolonization means #LandBack.” The statue broke at the ankles, leaving only the feet on the base.

What was even more provocative than the toppling of the statues by Native activists and their accomplices, was the response by the Catholic Church, which not only condemned the actions of the Native activists, but also spiritually chastised them. In both Portland and San Rafael, the reaction by the Church was to perform exorcisms.

The purpose of an exorcism, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, is to expel demons or “the liberation from demonic possession through the spiritual authority which Jesus entrusted to his Church.”

In other words, Native activism and demands for land back were deemed blasphemous and evil by two archbishops and were determined to require exorcism.

In Portland, Archbishop Alexander K. Sample led 225 members of his congregation to a city park where he prayed a rosary for peace and conducted an exorcism on October 17, six days after the “Indigenous People’s Day of Rage.” Archbishop Sample stated that there was no better time to come together to pray for peace than in the wake of social unrest and on the eve of the elections. His exorcism was a direct response to Indigenous-led efforts that demanded land back.

San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone held an exorcism on the same day as the one performed in Portland and after the toppling of Saint Junipero Serra’s statue in San Rafael. In his performance of the exorcism, he prayed that God would purify the mission of evil spirits as well as the hearts of those who perpetrated blasphemy. Was he responding to a “demonic possession” or was he exorcising the political motivations of those he did not agree with? Perhaps both, as he also stated that the toppling of the statue was an attack on the Catholic faith that took place on their own property. However, the mission is only Church property because of Native dispossession through conquest and missionization.

The conquest of the Americas by European nations was, as Saint Serra had deemed his own work, a “spiritual conquest.” From the doctrine of discovery to manifest destiny, the possession of Native land was rationalized as divine – from God. Those who threaten colonial possession are attacking the theological rationalization of possession, not their faith.

Demands for land back interfere with the doctrine that enabled Native land to be exorcised from them. Archbishop Cordileone’s exorcism was in the maintenance of property that had been stolen from Indigenous people long ago, and Archbishop Sample’s was in the maintenance of peace and the status quo of Native dispossession.

With a majority-Christian population in the United States and other nations in the Americas, demands for the return of land and decolonization have more to reckon with than racial injustice and white supremacy. Christians must also consider how dominant strains of Christian theology rationalized conquest and its ongoing structures of dispossession. Can a religion, made up of many sects, shift its framework to help end continued Native dispossession and its rationalization? Can we come together to overturn a racialized theological doctrine that functioned through violence and was adopted into a nation’s legal system? Can we imagine life beyond rage and the racialized spiritual possession of stolen land?

The Doctrine of Discovery was the primary international law developed in the 15th and 16th centuries through a series of papal bulls (Catholic decrees) that divided the Americas for white European conquest and authorized the enslavement of non-Christians. In 1823 the Doctrine of Discovery was cited in the U.S. Supreme Court case Johnson v. M’Intosh. Chief Justice John Marshall declared in his ruling that Indians only held occupancy rights to land — ownership belonged to the European nation that discovered it. This case further legalized the theft of Native lands. It continues to be a foundational principal of U.S. property law and has been cited as recently as 2005 by the U.S. Supreme Court (City of Sherrill v. Oneida Nation of Indians) to diminish Native American land rights.

In 2009 the Episcopal Church passed a resolution that repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery. It was the first Christian denomination to do so and has since been followed by several other denominations, including the Anglican Church of Canada (2010), the Religious Society of Friends/Quakers (2009 and 2012), the World Council of Churches (2012), the United Methodist Church (2012), the United Church of Christ (2013) and the Mennonite Church (2014).

Decolonization and land return are as possible as repudiating the legal justification of land theft. Social, cultural, governmental and economic systems are constantly changing, but the land remains — in the hands of the dispossessors. When our faith is held above what we know is true — we will prolong doing what is right.

Native peoples are not ancient peoples of the past only remembered on days such as Thanksgiving, just as our mourning is not all that we are. Native peoples are a myriad of things, including activists who demand land back — which is not a demonic request. Our land can be returned, and we can work together to heal and imagine a future beyond white supremacy and dispossession.

The acts of mourning and resistance taking place today build on the energy of Indigenous People’s Day 2020, which was also a day of uprising. On October 11, 2020, also called “Indigenous People’s Day of Rage,” participants around the country took part in actions such as de-monumenting — the toppling of statues of individuals dedicated to racial nation-building.

In response to Indigenous-led efforts that demanded land back and the toppling of statues, Catholic Church leaders in Oregon and California deemed it necessary to perform exorcisms, thereby casting Indigenous protest as demonic.

The toppled statues included President Abraham Lincoln, President Theodore Roosevelt and Father Junípero Serra, who founded California’s mission system (1769-1834) and was canonized into sainthood by the Catholic Church and Pope Francis in 2015.

What do these leaders whose statues were toppled have in common? They perpetrated and promoted devastating violence against Native peoples.

Abraham Lincoln was responsible for the largest mass execution in United States history when 38 Dakota were hanged in 1862 after being found guilty for their involvement in what is known as the “Minnesota Uprising.”

Theodore Roosevelt gave a speech in 1886 in New York that would have made today’s white supremacists blush when he declared: “I don’t go as far as to think that the only good Indian is the dead Indian, but I believe nine out of every ten are…” This was not his only foray in promoting racial genocide.

Junípero Serra is known for having committed cruel punishments against the Indians of California and enslaved them as part of Spain’s genocidal conquest.

Last month, “Land Back” and “Dakota 38” were scrawled on the base of the now-toppled Lincoln statue in Portland, Oregon. The political statements and demands for land return reveal a Native decolonial spirit based in resistance continuing through multiple generations.

The “Indigenous People’s Day of Rage” came after months of protests in Portland in support of Black Lives Matter. The resistance enacted in Portland coincides with demands for both abolition (the end of racialized policing and imprisonment) and decolonization (the return of land and regeneration of life outside of colonialism). Both of these notions encompass a multifaceted imagining of life beyond white supremacy.

In San Rafael, California, Native activists gathered at the Spanish mission that had been the site of California Indian enslavement. Activists, who included members of the Coast Miwok of Marin, first poured red paint on the statue of Serra and then pulled it down with ropes, while other protesters held signs that read: “Land Back Now” and “We Stand on Unceded Land – Decolonization means #LandBack.” The statue broke at the ankles, leaving only the feet on the base.

What was even more provocative than the toppling of the statues by Native activists and their accomplices, was the response by the Catholic Church, which not only condemned the actions of the Native activists, but also spiritually chastised them. In both Portland and San Rafael, the reaction by the Church was to perform exorcisms.

The purpose of an exorcism, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, is to expel demons or “the liberation from demonic possession through the spiritual authority which Jesus entrusted to his Church.”

In other words, Native activism and demands for land back were deemed blasphemous and evil by two archbishops and were determined to require exorcism.

In Portland, Archbishop Alexander K. Sample led 225 members of his congregation to a city park where he prayed a rosary for peace and conducted an exorcism on October 17, six days after the “Indigenous People’s Day of Rage.” Archbishop Sample stated that there was no better time to come together to pray for peace than in the wake of social unrest and on the eve of the elections. His exorcism was a direct response to Indigenous-led efforts that demanded land back.

San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone held an exorcism on the same day as the one performed in Portland and after the toppling of Saint Junipero Serra’s statue in San Rafael. In his performance of the exorcism, he prayed that God would purify the mission of evil spirits as well as the hearts of those who perpetrated blasphemy. Was he responding to a “demonic possession” or was he exorcising the political motivations of those he did not agree with? Perhaps both, as he also stated that the toppling of the statue was an attack on the Catholic faith that took place on their own property. However, the mission is only Church property because of Native dispossession through conquest and missionization.

The conquest of the Americas by European nations was, as Saint Serra had deemed his own work, a “spiritual conquest.” From the doctrine of discovery to manifest destiny, the possession of Native land was rationalized as divine – from God. Those who threaten colonial possession are attacking the theological rationalization of possession, not their faith.

Demands for land back interfere with the doctrine that enabled Native land to be exorcised from them. Archbishop Cordileone’s exorcism was in the maintenance of property that had been stolen from Indigenous people long ago, and Archbishop Sample’s was in the maintenance of peace and the status quo of Native dispossession.

With a majority-Christian population in the United States and other nations in the Americas, demands for the return of land and decolonization have more to reckon with than racial injustice and white supremacy. Christians must also consider how dominant strains of Christian theology rationalized conquest and its ongoing structures of dispossession. Can a religion, made up of many sects, shift its framework to help end continued Native dispossession and its rationalization? Can we come together to overturn a racialized theological doctrine that functioned through violence and was adopted into a nation’s legal system? Can we imagine life beyond rage and the racialized spiritual possession of stolen land?

The Doctrine of Discovery was the primary international law developed in the 15th and 16th centuries through a series of papal bulls (Catholic decrees) that divided the Americas for white European conquest and authorized the enslavement of non-Christians. In 1823 the Doctrine of Discovery was cited in the U.S. Supreme Court case Johnson v. M’Intosh. Chief Justice John Marshall declared in his ruling that Indians only held occupancy rights to land — ownership belonged to the European nation that discovered it. This case further legalized the theft of Native lands. It continues to be a foundational principal of U.S. property law and has been cited as recently as 2005 by the U.S. Supreme Court (City of Sherrill v. Oneida Nation of Indians) to diminish Native American land rights.

In 2009 the Episcopal Church passed a resolution that repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery. It was the first Christian denomination to do so and has since been followed by several other denominations, including the Anglican Church of Canada (2010), the Religious Society of Friends/Quakers (2009 and 2012), the World Council of Churches (2012), the United Methodist Church (2012), the United Church of Christ (2013) and the Mennonite Church (2014).

Decolonization and land return are as possible as repudiating the legal justification of land theft. Social, cultural, governmental and economic systems are constantly changing, but the land remains — in the hands of the dispossessors. When our faith is held above what we know is true — we will prolong doing what is right.

Native peoples are not ancient peoples of the past only remembered on days such as Thanksgiving, just as our mourning is not all that we are. Native peoples are a myriad of things, including activists who demand land back — which is not a demonic request. Our land can be returned, and we can work together to heal and imagine a future beyond white supremacy and dispossession.

Regrowing Indigenous Agriculture Could Nourish People, Cultures and the Land

European settlement, government policies and monoculture have nearly eradicated Native American farming practices. A growing movement is reclaiming them.

CHRISTINA GISH HILL - IN THESE TIMES

NOVEMBER 21, 2020

Historians know that turkey and corn were part of the first Thanksgiving, when Wampanoag peoples shared a harvest meal with the pilgrims of Plymouth plantation in Massachusetts. And traditional Native American farming practices tell us that squash and beans likely were part of that 1621 dinner too.

For centuries before Europeans reached North America, many Native Americans grew these foods together in one plot, along with the less familiar sunflower. They called the plants sisters to reflect how they thrived when they were cultivated together.

Today three-quarters of Native Americans live off of reservations, mainly in urban areas. And nationwide, many Native American communities lack access to healthy food. As a scholar of Indigenous studies focusing on Native relationships with the land, I began to wonder why Native farming practices had declined and what benefits could emerge from bringing them back.

To answer these questions, I am working with agronomist Marshall McDaniel, horticulturalist Ajay Nair, nutritionist Donna Winham and Native gardening projects in Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Our research project, “Reuniting the Three Sisters,” explores what it means to be a responsible caretaker of the land from the perspective of peoples who have been balancing agricultural production with sustainability for hundreds of years.

Abundant harvests

Historically, Native people throughout the Americas bred indigenous plant varieties specific to the growing conditions of their homelands. They selected seeds for many different traits, such as flavor, texture and color.

Native growers knew that planting corn, beans, squash and sunflowers together produced mutual benefits. Corn stalks created a trellis for beans to climb, and beans’ twining vines secured the corn in high winds. They also certainly observed that corn and bean plants growing together tended to be healthier than when raised separately. Today we know the reason: Bacteria living on bean plant roots pull nitrogen – an essential plant nutrient – from the air and convert it to a form that both beans and corn can use.

Squash plants contributed by shading the ground with their broad leaves, preventing weeds from growing and retaining water in the soil. Heritage squash varieties also had spines that discouraged deer and raccoons from visiting the garden for a snack. And sunflowers planted around the edges of the garden created a natural fence, protecting other plants from wind and animals and attracting pollinators.

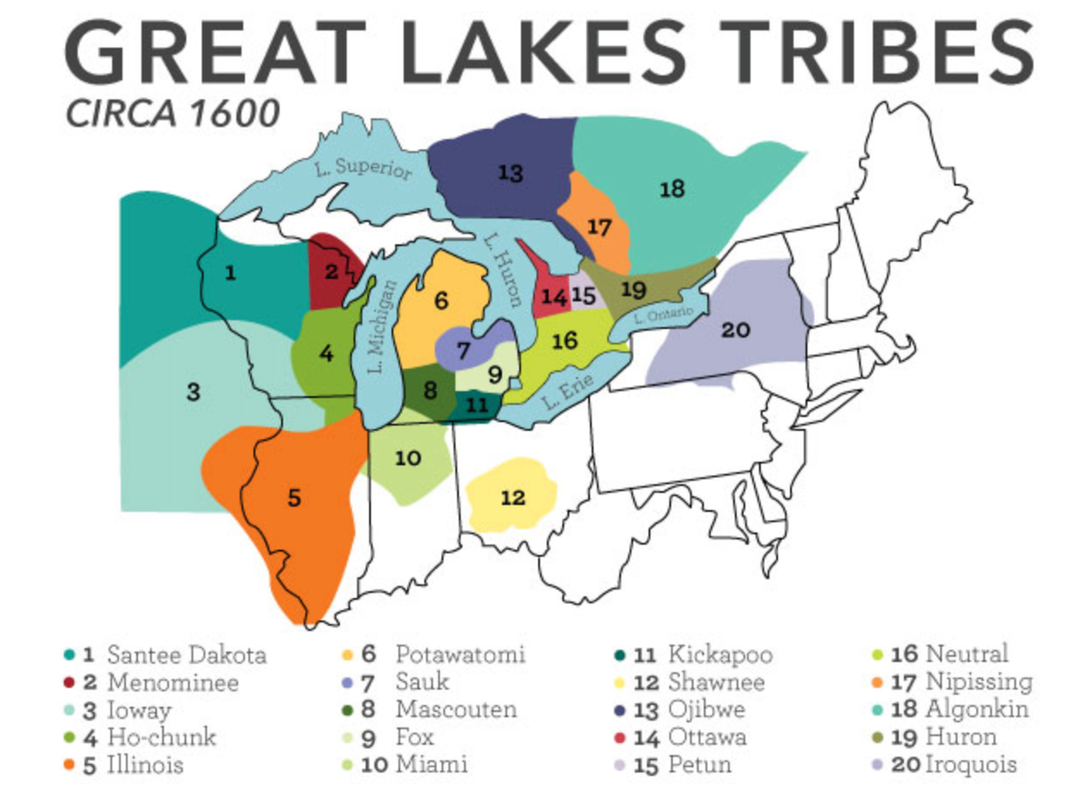

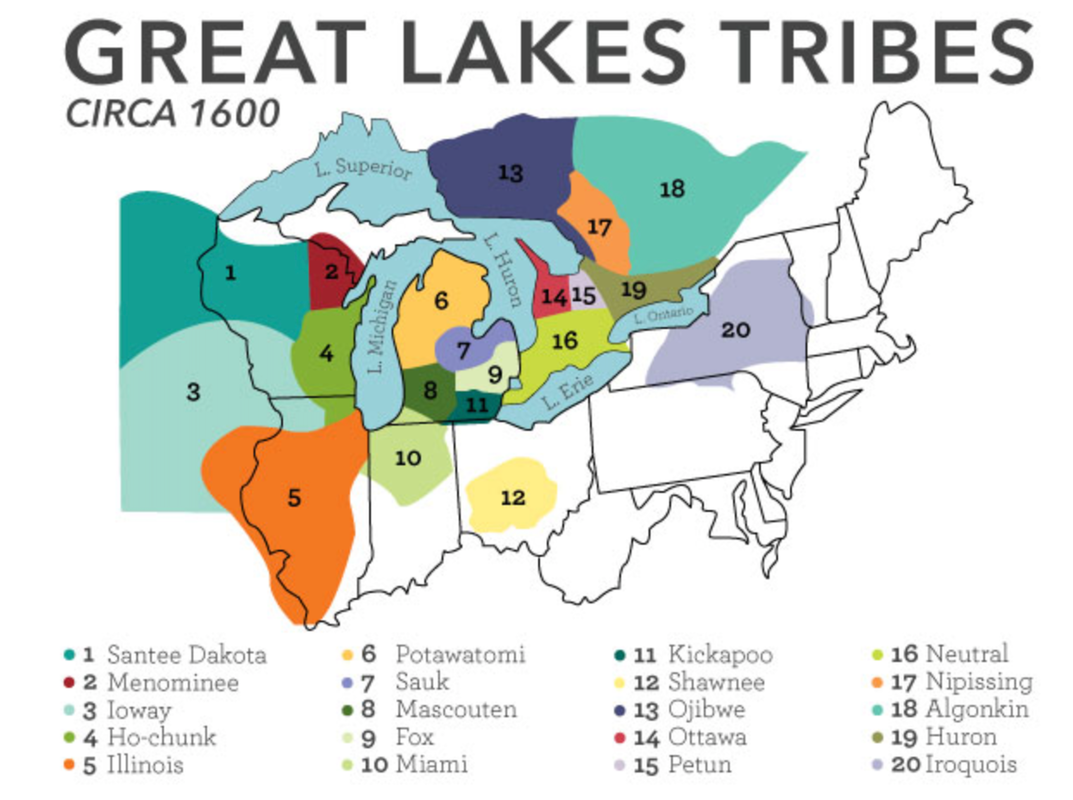

Interplanting these agricultural sisters produced bountiful harvests that sustained large Native communities and spurred fruitful trade economies. The first Europeans who reached the Americas were shocked at the abundant food crops they found. My research is exploring how, 200 years ago, Native American agriculturalists around the Great Lakes and along the Missouri and Red rivers fed fur traders with their diverse vegetable products.

Displaced from the land

As Euro-Americans settled permanently on the most fertile North American lands and acquired seeds that Native growers had carefully bred, they imposed policies that made Native farming practices impossible. In 1830 President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which made it official U.S. policy to force Native peoples from their home locations, pushing them onto subpar lands.

On reservations, U.S. government officials discouraged Native women from cultivating anything larger than small garden plots and pressured Native men to practice Euro-American style monoculture. Allotment policies assigned small plots to nuclear families, further limiting Native Americans’ access to land and preventing them from using communal farming practices.

Native children were forced to attend boarding schools, where they had no opportunity to learn Native agriculture techniques or preservation and preparation of Indigenous foods. Instead they were forced to eat Western foods, turning their palates away from their traditional preferences. Taken together, these policies almost entirely eradicated three sisters agriculture from Native communities in the Midwest by the 1930s.

Reviving Native agriculture

Today Native people all over the U.S. are working diligently to reclaim Indigenous varieties of corn, beans, squash, sunflowers and other crops. This effort is important for many reasons.

Improving Native people’s access to healthy, culturally appropriate foods will help lower rates of diabetes and obesity, which affect Native Americans at disproportionately high rates. Sharing traditional knowledge about agriculture is a way for elders to pass cultural information along to younger generations. Indigenous growing techniques also protect the lands that Native nations now inhabit, and can potentially benefit the wider ecosystems around them.

But Native communities often lack access to resources such as farming equipment, soil testing, fertilizer and pest prevention techniques. This is what inspired Iowa State University’s Three Sisters Gardening Project. We work collaboratively with Native farmers at Tsyunhehkw, a community agriculture program, and the Ohelaku Corn Growers Co-Op on the Oneida reservation in Wisconsin; the Nebraska Indian College, which serves the Omaha and Santee Sioux in Nebraska; and Dream of Wild Health, a nonprofit organization that works to reconnect the Native American community in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, with traditional Native plants and their culinary, medicinal and spiritual uses.

We are growing three sisters research plots at ISU’s Horticulture Farm and in each of these communities. Our project also runs workshops on topics of interests to Native gardeners, encourages local soil health testing and grows rare seeds to rematriate them, or return them to their home communities.

The monocropping industrial agricultural systems that produce much of the U.S. food supply harms the environment, rural communities and human health and safety in many ways. By growing corn, beans and squash in research plots, we are helping to quantify how intercropping benefits both plants and soil.

By documenting limited nutritional offerings at reservation grocery stores, we are demonstrating the need for Indigenous gardens in Native communities. By interviewing Native growers and elders knowledgeable about foodways, we are illuminating how healing Indigenous gardening practices can be for Native communities and people – their bodies, minds and spirits.

Our Native collaborators are benefiting from the project through rematriation of rare seeds grown in ISU plots, workshops on topics they select and the new relationships they are building with Native gardeners across the Midwest. As researchers, we are learning about what it means to work collaboratively and to conduct research that respects protocols our Native collaborators value, such as treating seeds, plants and soil in a culturally appropriate manner. By listening with humility, we are working to build a network where we can all learn from one another.

For centuries before Europeans reached North America, many Native Americans grew these foods together in one plot, along with the less familiar sunflower. They called the plants sisters to reflect how they thrived when they were cultivated together.

Today three-quarters of Native Americans live off of reservations, mainly in urban areas. And nationwide, many Native American communities lack access to healthy food. As a scholar of Indigenous studies focusing on Native relationships with the land, I began to wonder why Native farming practices had declined and what benefits could emerge from bringing them back.

To answer these questions, I am working with agronomist Marshall McDaniel, horticulturalist Ajay Nair, nutritionist Donna Winham and Native gardening projects in Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Our research project, “Reuniting the Three Sisters,” explores what it means to be a responsible caretaker of the land from the perspective of peoples who have been balancing agricultural production with sustainability for hundreds of years.

Abundant harvests

Historically, Native people throughout the Americas bred indigenous plant varieties specific to the growing conditions of their homelands. They selected seeds for many different traits, such as flavor, texture and color.

Native growers knew that planting corn, beans, squash and sunflowers together produced mutual benefits. Corn stalks created a trellis for beans to climb, and beans’ twining vines secured the corn in high winds. They also certainly observed that corn and bean plants growing together tended to be healthier than when raised separately. Today we know the reason: Bacteria living on bean plant roots pull nitrogen – an essential plant nutrient – from the air and convert it to a form that both beans and corn can use.

Squash plants contributed by shading the ground with their broad leaves, preventing weeds from growing and retaining water in the soil. Heritage squash varieties also had spines that discouraged deer and raccoons from visiting the garden for a snack. And sunflowers planted around the edges of the garden created a natural fence, protecting other plants from wind and animals and attracting pollinators.

Interplanting these agricultural sisters produced bountiful harvests that sustained large Native communities and spurred fruitful trade economies. The first Europeans who reached the Americas were shocked at the abundant food crops they found. My research is exploring how, 200 years ago, Native American agriculturalists around the Great Lakes and along the Missouri and Red rivers fed fur traders with their diverse vegetable products.

Displaced from the land

As Euro-Americans settled permanently on the most fertile North American lands and acquired seeds that Native growers had carefully bred, they imposed policies that made Native farming practices impossible. In 1830 President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which made it official U.S. policy to force Native peoples from their home locations, pushing them onto subpar lands.

On reservations, U.S. government officials discouraged Native women from cultivating anything larger than small garden plots and pressured Native men to practice Euro-American style monoculture. Allotment policies assigned small plots to nuclear families, further limiting Native Americans’ access to land and preventing them from using communal farming practices.

Native children were forced to attend boarding schools, where they had no opportunity to learn Native agriculture techniques or preservation and preparation of Indigenous foods. Instead they were forced to eat Western foods, turning their palates away from their traditional preferences. Taken together, these policies almost entirely eradicated three sisters agriculture from Native communities in the Midwest by the 1930s.

Reviving Native agriculture

Today Native people all over the U.S. are working diligently to reclaim Indigenous varieties of corn, beans, squash, sunflowers and other crops. This effort is important for many reasons.

Improving Native people’s access to healthy, culturally appropriate foods will help lower rates of diabetes and obesity, which affect Native Americans at disproportionately high rates. Sharing traditional knowledge about agriculture is a way for elders to pass cultural information along to younger generations. Indigenous growing techniques also protect the lands that Native nations now inhabit, and can potentially benefit the wider ecosystems around them.

But Native communities often lack access to resources such as farming equipment, soil testing, fertilizer and pest prevention techniques. This is what inspired Iowa State University’s Three Sisters Gardening Project. We work collaboratively with Native farmers at Tsyunhehkw, a community agriculture program, and the Ohelaku Corn Growers Co-Op on the Oneida reservation in Wisconsin; the Nebraska Indian College, which serves the Omaha and Santee Sioux in Nebraska; and Dream of Wild Health, a nonprofit organization that works to reconnect the Native American community in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, with traditional Native plants and their culinary, medicinal and spiritual uses.

We are growing three sisters research plots at ISU’s Horticulture Farm and in each of these communities. Our project also runs workshops on topics of interests to Native gardeners, encourages local soil health testing and grows rare seeds to rematriate them, or return them to their home communities.

The monocropping industrial agricultural systems that produce much of the U.S. food supply harms the environment, rural communities and human health and safety in many ways. By growing corn, beans and squash in research plots, we are helping to quantify how intercropping benefits both plants and soil.

By documenting limited nutritional offerings at reservation grocery stores, we are demonstrating the need for Indigenous gardens in Native communities. By interviewing Native growers and elders knowledgeable about foodways, we are illuminating how healing Indigenous gardening practices can be for Native communities and people – their bodies, minds and spirits.

Our Native collaborators are benefiting from the project through rematriation of rare seeds grown in ISU plots, workshops on topics they select and the new relationships they are building with Native gardeners across the Midwest. As researchers, we are learning about what it means to work collaboratively and to conduct research that respects protocols our Native collaborators value, such as treating seeds, plants and soil in a culturally appropriate manner. By listening with humility, we are working to build a network where we can all learn from one another.

How Native Americans’ right to vote has been systematically violated for generations

In the new book Voting in Indian Country, Jean Reith Schroedel weaves together historical and contemporary voting rights conflicts as the election nears

Nina Lakhani in New York

the guardian

Fri 16 Oct 2020 08.00 EDT

oter suppression has taken centre stage in the race to elect potentially the 46th president of the United States. But we’ve heard little about the 5.2 million Native Americans whose ancestors have called this land home before there was a US president.

The rights of indigenous communities – including the right to vote – have been systematically violated for generations with devastating consequences for access to clean air and water, health, education, economic opportunities, housing and sovereignty. Voter turnout for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives is the lowest in the country, and about one in three eligible voters (1.2 million people) are not registered to vote, according to the National Congress of American Indians.

In a new book, Voting in Indian County: The View from the Trenches, Jean Reith Schroedel, professor emerita of political science at Claremont Graduate University, weaves together historical and contemporary voting rights conflicts.

Is the right to vote struggle for Native Americans distinct from the wider struggle faced by marginalized groups in the US?

One thing few Americans understand is that American Indians and Native Alaskans were the last group in the United States to get citizenship and to get the vote. Even after the civil war and the Reconstruction (13th, 14th and 15th) amendments there was a supreme court decision that said indigenous people could never become US citizens, and some laws used to disenfranchise them were still in place in 1975. In fact first-generation violations used to deny – not just dilute voting rights – were in place for much longer for Native Americans than any other group. It’s impossible to understand contemporary voter suppression in Indian Country without understanding this historical context.

Why didn’t the American Indian Citizenship Act 1924 nor the Voting Rights Act (VRA) 1965 guarantee Native Americans equal access to the ballot box?

The motivation for the VRA was the egregious treatment of black people in the south, and for the first 10 years there was a question over whether it even applied to American Indian and Native Alaskan populations. It wasn’t really discussed until a civil rights commission report in 1975 which included cases from South Dakota and Arizona that showed equally egregious discrimination and absolute denial of right to vote towards Native Americans – and also Latinos.

When voter suppression is discussed by politicians, advocates and journalists, it’s mostly about African American voters, and to a lesser degree Latinos. Why are Native Americans still excluded from the conversation?

Firstly they are a small population and secondly most of the most egregious abuses routinely occur in rural isolated parts of Indian Country where there is little media focus. But it’s happening – take Jackson county in South Dakota, a state where the governor has done little to protect people from Covid. The county council has just decided to close the legally mandated early voting centre on the Pine Ridge Reservation, citing concerns about Covid, but not in the voting site in Kadoka, where the white people go. Regardless of the intent, this will absolutely have a detrimental effect on Native people’s ability to vote. And South Dakota, like many other states, is also a very hard place for Native people to vote by mail. In the primary, the number of people who registered to vote by mail increased by 1,000% overall but there was no increase among reservation communities. In Oglala county, which includes the eastern part of Pine Ridge, turnout was about 10%.

The right to vote by mail is a hot political and civil rights issue in the 2020 election – could it help increase turnout in Indian Country?

No, voting by mail is very challenging for Native Americans for multiple reasons. First and foremost, most reservations do not have home mail delivery. Instead, people need to travel to post offices or postal provide sites – little places that offer minimal mail services and are located in places like gas stations and mini-marts. Take the Navajo Nation that encompasses 27,425 square miles – it’s larger than West Virginia, yet there are only 40 places where people can send and receive mail. In West Virginia, there are 725. Not a single PO box on the Navajo Nation has 24-hour access.

Preliminary data from my new research shows that all the mail sent from post offices off-reservation arrived at the election office within one to three days. Whereas around half sent from the reservation took three to 10 days. Rural whites are doing a whole lot better than rural Native Americans. This isn’t the only challenge: South Dakota requires mail ballots to be notarized but there are no notaries on reservations. And the level of trust in voting is generally low among Native Americans, but drops dramatically when asked about voting by mail.

Are Native Americans denied the right to vote because of ID requirements mandated by some states, supposedly to curtail voter fraud?

It can make it very difficult for people who live on reservations where many roads don’t have names or numbers – so-called non-standard addresses, which are very problematic in states requiring IDs with residential addresses. A number of states like South Dakota have chosen to make it a felony offense with prison terms and fines if someone votes using an address different to the one given to register, even though unstable housing is a big issue on reservations, and people crash in different places all the time.

Will Native Americans who only have tribal ID be refused the vote?

Tribal ID has not been accepted in a number of states in the past, including North Dakota and Minnesota. In some places the problem is that the tribal ID may not have a residential street address, because those do not exist on many reservations, or that government entities have in their records an address that was arbitrarily assigned to people with non-standard addresses, and that address does not match another assigned address on a different government list. But with respect to the upcoming election, we honestly won’t know how big an issue it is until people try to vote.

We’ve heard about felony disenfranchisement in black communities, especially in states like Florida. Does this impact Native Americans too?

It’s a major unstudied issue but what we do know is that laws passed after Reconstruction and the VRA specifically to disenfranchise African Americans were also passed in places which didn’t have black people. For example, Idaho put in place felony disenfranchisement around when it became the state, at a time when census data shows there were only 88 black people – it was designed to disenfranchise Native people. Half the states with harshest felony disenfranchisement don’t have many black people, but have big Native Americans or Latino populations.

Why are the Dakotas so important in the struggle for equality at the ballot box?

The Dakotas are the heart of what was the great Sioux Nations, who put together a cross-nation resistance to the incursion by Europeans, US military and militias. It’s a flashpoint where some of the worst massacres took place and it’s been one of the worst places for suppression of the Native American vote. North Dakota has passed one law after another that made it harder and harder for people to vote, which I think [most recently] was a retaliation to further disenfranchise Native people for standing up against the Dakota Access pipeline.

In South Dakota, more than a quarter of the 2016 registered voters in Todd county – which is the Rosebud Sioux – had been purged by 2020. This is huge. Todd county is an unorganized county, so the administration of elections is handled by an adjacent white county. These are red states, so little donor money goes into voting rights, but the white population is ageing, and younger whites are leaving the state. It’s going to be fascinating to watch how the Dakotas deal with the much larger Native American voting populations over the next 10 years.

Which are the states to watch in this election for potential voter suppression of Native American votes?

Arizona because it is a swing state and has all of the above issues; Montana, which can be considered a success story with regards to Native American representation in recent years, but where a lack of in-person voting could have a big impact. Alaska and Nevada have issues, and of course the Dakotas.

The rights of indigenous communities – including the right to vote – have been systematically violated for generations with devastating consequences for access to clean air and water, health, education, economic opportunities, housing and sovereignty. Voter turnout for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives is the lowest in the country, and about one in three eligible voters (1.2 million people) are not registered to vote, according to the National Congress of American Indians.

In a new book, Voting in Indian County: The View from the Trenches, Jean Reith Schroedel, professor emerita of political science at Claremont Graduate University, weaves together historical and contemporary voting rights conflicts.

Is the right to vote struggle for Native Americans distinct from the wider struggle faced by marginalized groups in the US?

One thing few Americans understand is that American Indians and Native Alaskans were the last group in the United States to get citizenship and to get the vote. Even after the civil war and the Reconstruction (13th, 14th and 15th) amendments there was a supreme court decision that said indigenous people could never become US citizens, and some laws used to disenfranchise them were still in place in 1975. In fact first-generation violations used to deny – not just dilute voting rights – were in place for much longer for Native Americans than any other group. It’s impossible to understand contemporary voter suppression in Indian Country without understanding this historical context.

Why didn’t the American Indian Citizenship Act 1924 nor the Voting Rights Act (VRA) 1965 guarantee Native Americans equal access to the ballot box?

The motivation for the VRA was the egregious treatment of black people in the south, and for the first 10 years there was a question over whether it even applied to American Indian and Native Alaskan populations. It wasn’t really discussed until a civil rights commission report in 1975 which included cases from South Dakota and Arizona that showed equally egregious discrimination and absolute denial of right to vote towards Native Americans – and also Latinos.

When voter suppression is discussed by politicians, advocates and journalists, it’s mostly about African American voters, and to a lesser degree Latinos. Why are Native Americans still excluded from the conversation?

Firstly they are a small population and secondly most of the most egregious abuses routinely occur in rural isolated parts of Indian Country where there is little media focus. But it’s happening – take Jackson county in South Dakota, a state where the governor has done little to protect people from Covid. The county council has just decided to close the legally mandated early voting centre on the Pine Ridge Reservation, citing concerns about Covid, but not in the voting site in Kadoka, where the white people go. Regardless of the intent, this will absolutely have a detrimental effect on Native people’s ability to vote. And South Dakota, like many other states, is also a very hard place for Native people to vote by mail. In the primary, the number of people who registered to vote by mail increased by 1,000% overall but there was no increase among reservation communities. In Oglala county, which includes the eastern part of Pine Ridge, turnout was about 10%.

The right to vote by mail is a hot political and civil rights issue in the 2020 election – could it help increase turnout in Indian Country?

No, voting by mail is very challenging for Native Americans for multiple reasons. First and foremost, most reservations do not have home mail delivery. Instead, people need to travel to post offices or postal provide sites – little places that offer minimal mail services and are located in places like gas stations and mini-marts. Take the Navajo Nation that encompasses 27,425 square miles – it’s larger than West Virginia, yet there are only 40 places where people can send and receive mail. In West Virginia, there are 725. Not a single PO box on the Navajo Nation has 24-hour access.

Preliminary data from my new research shows that all the mail sent from post offices off-reservation arrived at the election office within one to three days. Whereas around half sent from the reservation took three to 10 days. Rural whites are doing a whole lot better than rural Native Americans. This isn’t the only challenge: South Dakota requires mail ballots to be notarized but there are no notaries on reservations. And the level of trust in voting is generally low among Native Americans, but drops dramatically when asked about voting by mail.

Are Native Americans denied the right to vote because of ID requirements mandated by some states, supposedly to curtail voter fraud?

It can make it very difficult for people who live on reservations where many roads don’t have names or numbers – so-called non-standard addresses, which are very problematic in states requiring IDs with residential addresses. A number of states like South Dakota have chosen to make it a felony offense with prison terms and fines if someone votes using an address different to the one given to register, even though unstable housing is a big issue on reservations, and people crash in different places all the time.

Will Native Americans who only have tribal ID be refused the vote?

Tribal ID has not been accepted in a number of states in the past, including North Dakota and Minnesota. In some places the problem is that the tribal ID may not have a residential street address, because those do not exist on many reservations, or that government entities have in their records an address that was arbitrarily assigned to people with non-standard addresses, and that address does not match another assigned address on a different government list. But with respect to the upcoming election, we honestly won’t know how big an issue it is until people try to vote.

We’ve heard about felony disenfranchisement in black communities, especially in states like Florida. Does this impact Native Americans too?

It’s a major unstudied issue but what we do know is that laws passed after Reconstruction and the VRA specifically to disenfranchise African Americans were also passed in places which didn’t have black people. For example, Idaho put in place felony disenfranchisement around when it became the state, at a time when census data shows there were only 88 black people – it was designed to disenfranchise Native people. Half the states with harshest felony disenfranchisement don’t have many black people, but have big Native Americans or Latino populations.

Why are the Dakotas so important in the struggle for equality at the ballot box?

The Dakotas are the heart of what was the great Sioux Nations, who put together a cross-nation resistance to the incursion by Europeans, US military and militias. It’s a flashpoint where some of the worst massacres took place and it’s been one of the worst places for suppression of the Native American vote. North Dakota has passed one law after another that made it harder and harder for people to vote, which I think [most recently] was a retaliation to further disenfranchise Native people for standing up against the Dakota Access pipeline.

In South Dakota, more than a quarter of the 2016 registered voters in Todd county – which is the Rosebud Sioux – had been purged by 2020. This is huge. Todd county is an unorganized county, so the administration of elections is handled by an adjacent white county. These are red states, so little donor money goes into voting rights, but the white population is ageing, and younger whites are leaving the state. It’s going to be fascinating to watch how the Dakotas deal with the much larger Native American voting populations over the next 10 years.

Which are the states to watch in this election for potential voter suppression of Native American votes?

Arizona because it is a swing state and has all of the above issues; Montana, which can be considered a success story with regards to Native American representation in recent years, but where a lack of in-person voting could have a big impact. Alaska and Nevada have issues, and of course the Dakotas.

Oklahoma is – and always has been – Native land

Dwanna L. McKay, Colorado College - the conversation

July 16, 2020 8.12am EDT

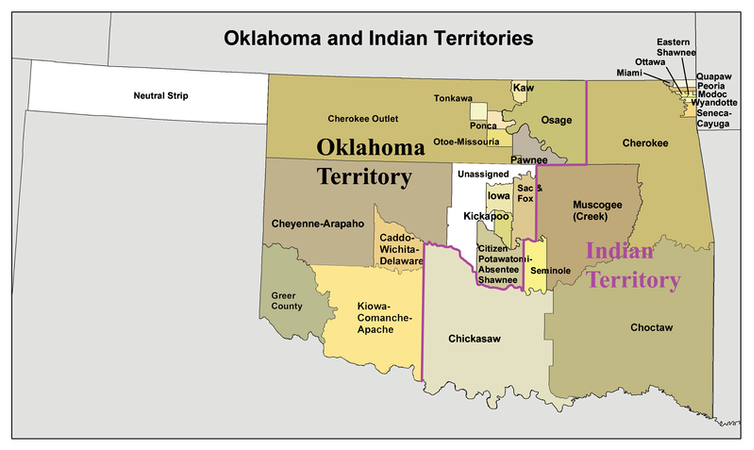

Some Oklahomans are expressing trepidation about the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that much of the eastern part of the state belongs to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. They wonder whether they must now pay taxes to or be governed by the Muscogee.

In alarmist language, Sen. Ted Cruz of neighboring Texas tweeted that the Supreme Court “just gave away half of Oklahoma, literally. Manhattan is next.”

In fact, the landmark July 9 decision applies only to criminal law. It gives federal and tribal courts jurisdiction over felonies committed by tribal citizens within the Creek reservation, not the state of Oklahoma.

Any shock that tribal nations have sovereignty over their own land reflects a serious misunderstanding of American history. For Oklahoma – indeed, all of North America – has always been, for lack of a better term, Indian Country.

‘Indian Country’

As both an educator and scholar, I work to correct the erasure of Indigenous histories through my research and teaching.

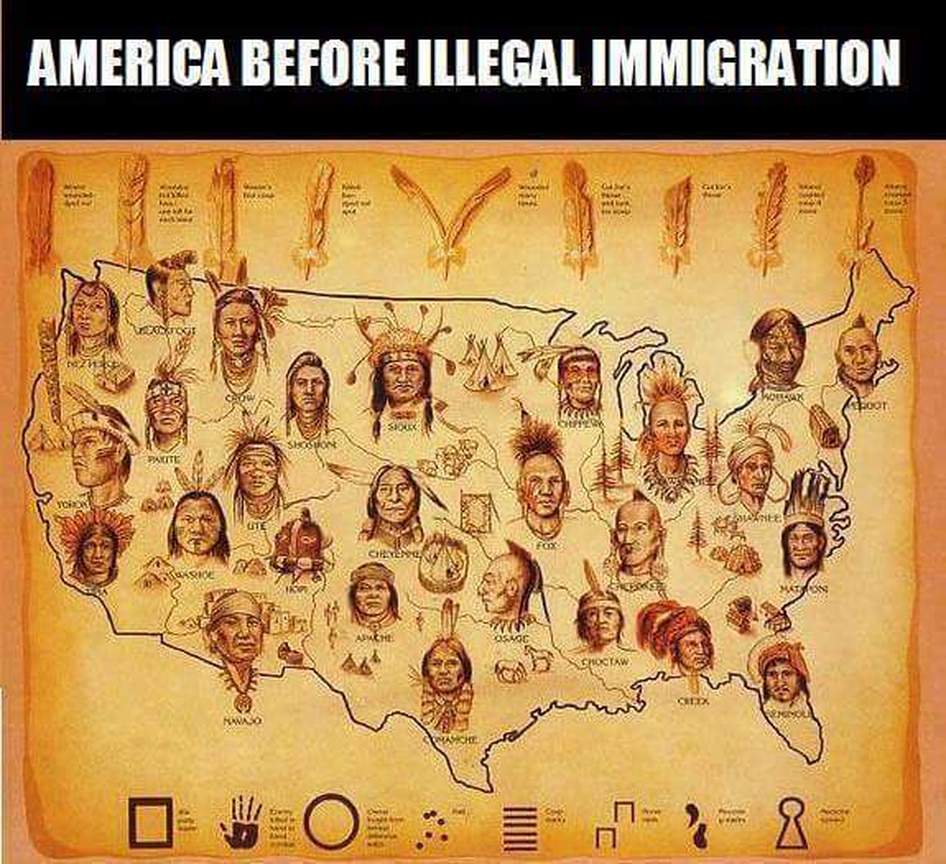

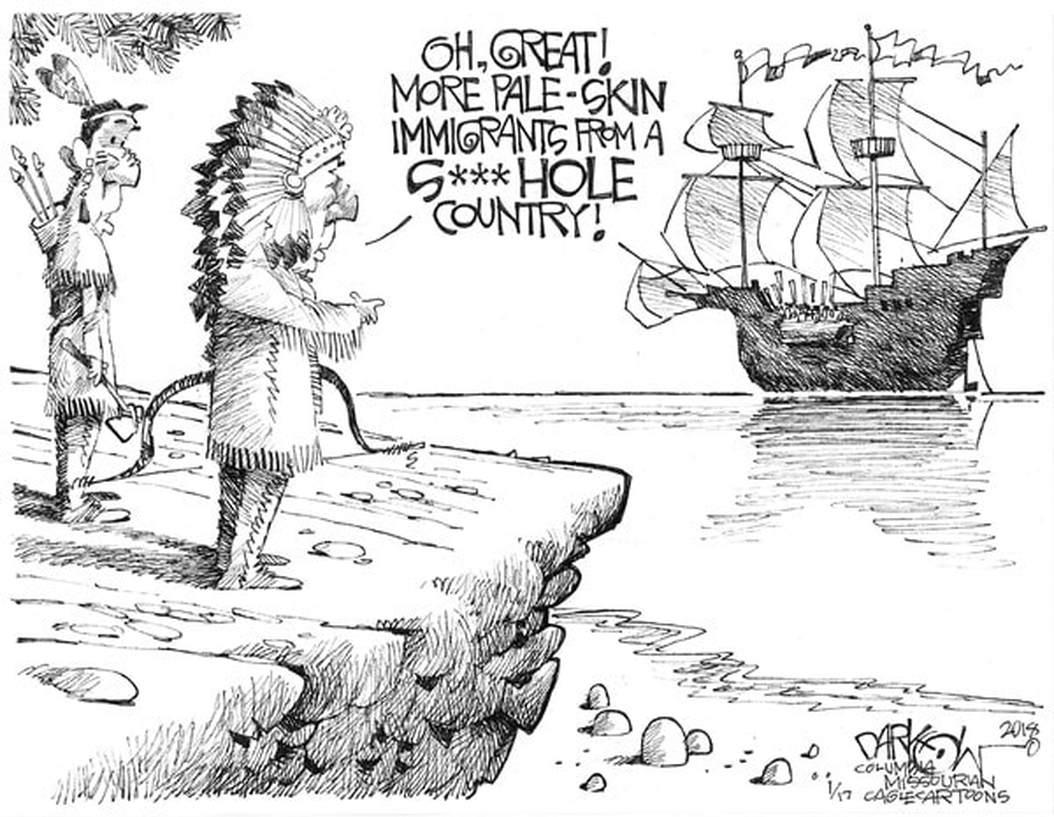

North America was not a vast, unpopulated wilderness when white colonizers arrived in 1620. Up to 100 million people of more than 1,000 sovereign Indigenous nations occupied the area that would become the United States. At the time, fewer than 80 million people lived in Europe.

America’s Indigenous nations were incredibly advanced, with extensive trade networks and economic centers, superior agricultural cultivation, well developed metalwork, pottery and weaving practices, as historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has comprehensively detailed.

Unlike Europe, with its periodic epidemics, North America had little disease, Dunbar-Ortiz says. People used herbal medicines, dentistry, surgery and daily hygienic bathing to salubrious effect.

Historically, Indigenous nations emphasized equity, consensus and community. Though individualism would come to define the United States, my research finds that Native Americans retain these values today, along with our guiding principles of respect, responsibility and reciprocity.

Broken promises and stolen lands

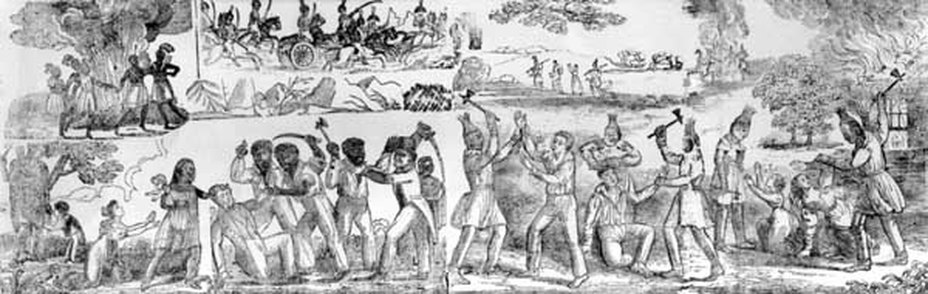

European and American colonizers did not hold these same values. From 1492 to 1900, they pushed inexorably westward across the North American continent, burning Native villages, destroying crops, committing sexual assaults, enslaving people and perpetrating massacres. The government did not punish these atrocities against Indigenous Nations and their citizens.

Citing the so-called “Doctrine of Discovery” and Manifest Destiny, U.S. policymakers argued that the federal government had a divine duty to fully develop the region. Racist in language and logic, they contended that “Indians” did not know how to work or to care for the land because they were inferior to whites.

Oklahoma was born of this institutionalized racism.

Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole nations – known as the Five Tribes – were forced from their ancestral homelands in the southeast and relocated to “Indian Territory,” as Oklahoma was then designated. Half of the Muscogee and Cherokee populations died from brutal and inhumane treatment as they were forcibly marched 2,200 miles across nine states to their new homelands in what most Americans call the Trail of Tears.

Indian Territory, which occupied all Oklahoma minus the panhandle, was almost 44 million acres of fertile rolling prairies, rivers and groves of enormous trees. Several Indian nations already lived in the area, including the Apache, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, Osage and Wichita.

Legally, Indian Territory was to belong to the tribal nations forever, and trespass by settlers was forbidden. But over the next two centuries, Congress would violate every one of the 375 treaties it made with Indian tribes as well as numerous statutory acts, according the United States Commission on Civil Rights.

By 1890, only about 25 million acres of Indian Territory remained. The Muscogee lost nearly half their lands in an 1866 Reconstruction-era treaty. And in 1889, almost 2 million acres in western Oklahoma were redesignated as “Unassigned Lands” and opened to “white settlement.” By 1890, the U.S. Census showed that only 28% of people in Indian Territory were actually “Indian.”

With statehood in 1907, Oklahoma assumed jurisdiction over all its territory, ultimately denying that the Muscogee had ever had a reservation there. That is the historic injustice corrected by the Supreme Court on July 9.

Respect, responsibility and reciprocity

Despite all the brutality and broken promises, the Five Tribes have contributed socially, culturally and economically to Oklahoma far beyond the shrinking bounds of their territories, in ways that benefit all residents.

The public school system created by the Choctaws shortly after their arrival became the model for Oklahoma schools that exists today. Last year, Oklahoma tribes contributed over US$130 million to Oklahoma public schools.

Oklahoma tribes also enrich Oklahoma’s economy, employing over 96,000 people – most of them non-Native – and attracting tourists with their cultural events. In 2017, Oklahoma tribes produced almost $13 billion in goods and services and paid out $4.6 billion in wages and benefits.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation, in particular, invests heavily in the state, creating businesses, building roads and providing jobs, health care and social services in 11 Oklahoma counties.

Still our homelands

Citizens of the Five Tribes have also contributed to broader American society.

Before the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II, the Choctaw Code Talkers used their language as code for the United States in World War I. Lt. Col Ernest Childers, a Muscogee, won the Medal of Honor for his service in World War II. U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, also a Muscogee, is the first Indigenous poet laureate. Mary Ross, a Cherokee, was the first known Indigenous woman engineer. And John Herrington, Chickasaw, was a NASA astronaut. These are but a few examples.

The strong collaborative leadership of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation was apparent after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Principal Chief David Hill’s official response.

“Today’s decision will allow the Nation to honor our ancestors by maintaining our established sovereignty and territorial boundaries,” Hill said, adding: “We will continue to work with federal and state law enforcement agencies to ensure that public safety will be maintained.”

In alarmist language, Sen. Ted Cruz of neighboring Texas tweeted that the Supreme Court “just gave away half of Oklahoma, literally. Manhattan is next.”

In fact, the landmark July 9 decision applies only to criminal law. It gives federal and tribal courts jurisdiction over felonies committed by tribal citizens within the Creek reservation, not the state of Oklahoma.

Any shock that tribal nations have sovereignty over their own land reflects a serious misunderstanding of American history. For Oklahoma – indeed, all of North America – has always been, for lack of a better term, Indian Country.

‘Indian Country’

As both an educator and scholar, I work to correct the erasure of Indigenous histories through my research and teaching.

North America was not a vast, unpopulated wilderness when white colonizers arrived in 1620. Up to 100 million people of more than 1,000 sovereign Indigenous nations occupied the area that would become the United States. At the time, fewer than 80 million people lived in Europe.

America’s Indigenous nations were incredibly advanced, with extensive trade networks and economic centers, superior agricultural cultivation, well developed metalwork, pottery and weaving practices, as historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has comprehensively detailed.

Unlike Europe, with its periodic epidemics, North America had little disease, Dunbar-Ortiz says. People used herbal medicines, dentistry, surgery and daily hygienic bathing to salubrious effect.

Historically, Indigenous nations emphasized equity, consensus and community. Though individualism would come to define the United States, my research finds that Native Americans retain these values today, along with our guiding principles of respect, responsibility and reciprocity.

Broken promises and stolen lands

European and American colonizers did not hold these same values. From 1492 to 1900, they pushed inexorably westward across the North American continent, burning Native villages, destroying crops, committing sexual assaults, enslaving people and perpetrating massacres. The government did not punish these atrocities against Indigenous Nations and their citizens.

Citing the so-called “Doctrine of Discovery” and Manifest Destiny, U.S. policymakers argued that the federal government had a divine duty to fully develop the region. Racist in language and logic, they contended that “Indians” did not know how to work or to care for the land because they were inferior to whites.

Oklahoma was born of this institutionalized racism.

Under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole nations – known as the Five Tribes – were forced from their ancestral homelands in the southeast and relocated to “Indian Territory,” as Oklahoma was then designated. Half of the Muscogee and Cherokee populations died from brutal and inhumane treatment as they were forcibly marched 2,200 miles across nine states to their new homelands in what most Americans call the Trail of Tears.

Indian Territory, which occupied all Oklahoma minus the panhandle, was almost 44 million acres of fertile rolling prairies, rivers and groves of enormous trees. Several Indian nations already lived in the area, including the Apache, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, Osage and Wichita.

Legally, Indian Territory was to belong to the tribal nations forever, and trespass by settlers was forbidden. But over the next two centuries, Congress would violate every one of the 375 treaties it made with Indian tribes as well as numerous statutory acts, according the United States Commission on Civil Rights.

By 1890, only about 25 million acres of Indian Territory remained. The Muscogee lost nearly half their lands in an 1866 Reconstruction-era treaty. And in 1889, almost 2 million acres in western Oklahoma were redesignated as “Unassigned Lands” and opened to “white settlement.” By 1890, the U.S. Census showed that only 28% of people in Indian Territory were actually “Indian.”

With statehood in 1907, Oklahoma assumed jurisdiction over all its territory, ultimately denying that the Muscogee had ever had a reservation there. That is the historic injustice corrected by the Supreme Court on July 9.

Respect, responsibility and reciprocity

Despite all the brutality and broken promises, the Five Tribes have contributed socially, culturally and economically to Oklahoma far beyond the shrinking bounds of their territories, in ways that benefit all residents.

The public school system created by the Choctaws shortly after their arrival became the model for Oklahoma schools that exists today. Last year, Oklahoma tribes contributed over US$130 million to Oklahoma public schools.

Oklahoma tribes also enrich Oklahoma’s economy, employing over 96,000 people – most of them non-Native – and attracting tourists with their cultural events. In 2017, Oklahoma tribes produced almost $13 billion in goods and services and paid out $4.6 billion in wages and benefits.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation, in particular, invests heavily in the state, creating businesses, building roads and providing jobs, health care and social services in 11 Oklahoma counties.

Still our homelands

Citizens of the Five Tribes have also contributed to broader American society.

Before the Navajo Code Talkers of World War II, the Choctaw Code Talkers used their language as code for the United States in World War I. Lt. Col Ernest Childers, a Muscogee, won the Medal of Honor for his service in World War II. U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, also a Muscogee, is the first Indigenous poet laureate. Mary Ross, a Cherokee, was the first known Indigenous woman engineer. And John Herrington, Chickasaw, was a NASA astronaut. These are but a few examples.

The strong collaborative leadership of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation was apparent after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Principal Chief David Hill’s official response.

“Today’s decision will allow the Nation to honor our ancestors by maintaining our established sovereignty and territorial boundaries,” Hill said, adding: “We will continue to work with federal and state law enforcement agencies to ensure that public safety will be maintained.”

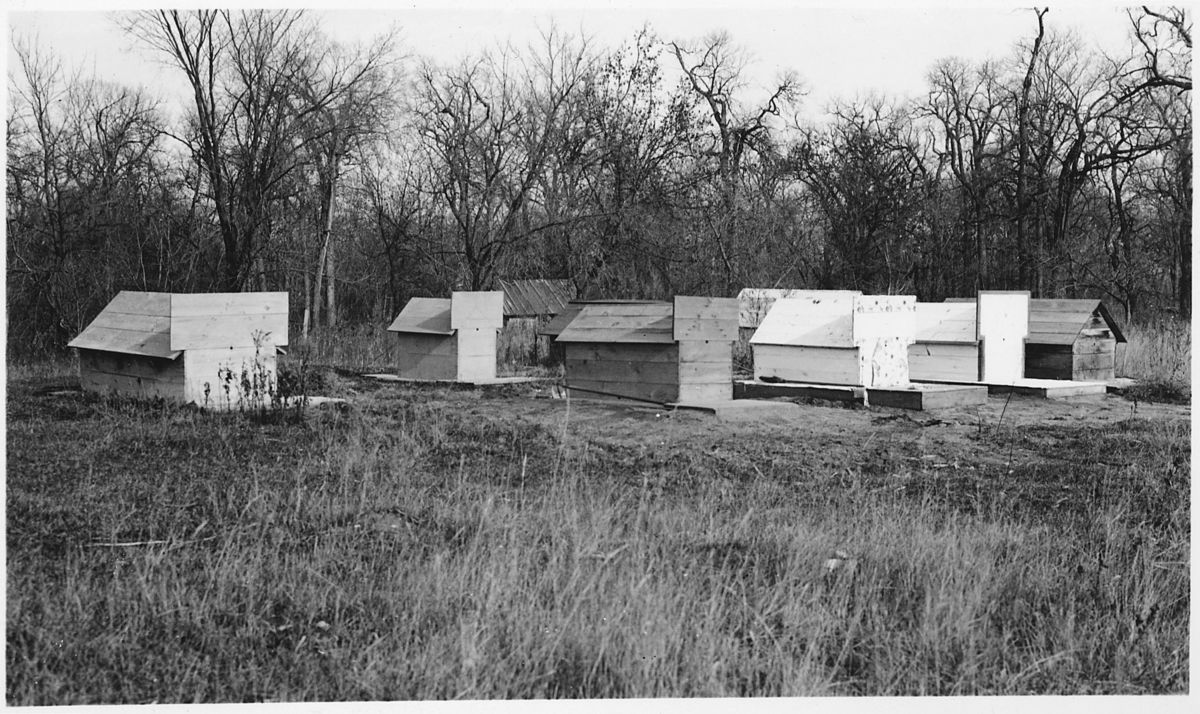

more environmental racism and screwing the poor!!!

US Environmental Protection Agency

Wood heaters too dirty to sell are clean enough to give to tribes, says EPA

Stoves that produce pollutants known to make people sick can be donated to tribes and Appalachian communities

Emily Holden in Washington

thew guardian

Thu 18 Jun 2020 06.00 EDT

Wood heaters that US regulators have deemed too dirty to sell can now be donated to tribal nations and Appalachian communities, under a program organized by a trade group and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Public health experts warn the donations could force more pollution on already vulnerable populations amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Wood-burning devices emit pollutants known to make people sick, including fine particle pollution and chemicals like benzene, formaldehyde, acrolein and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

“What’s disappointing is there have been efforts to really find solutions that help these areas in need, understanding they are looking to reduce home-heating costs,” said Lisa Rector, policy director of a non-profit association of north-eastern air quality agencies.

“It’s especially concerning that in this time when we’re dealing with a pandemic that attacks the respiratory system that we’re not really carefully thinking through this.”

But the industry and the communities set to receive the heaters argue they will replace much worse alternatives that are in use.

The divide highlights how environmental inequities persist in the US. Decisions about which Americans are best protected from pollution often come down to cost, with environmental racism dictating which communities get investments and which ones are subjected to more pollution and worse healthcare.

Billie Toledo, an environmental technician who co-leads the National Tribal Air Association working group on wood smoke, praised the program while acknowledging the donated stoves don’t meet the more updated rigorous standards for pollution.

“There might be an individual out there in a tribe within Indian country that is using a 55-gallon metal burn barrel,” Toledo said, and the replacement will be much safer despite the health risks.

Some tribes and non-profits have been working to replace the dirtiest stoves and educate people about best practices, including only burning dry wood to create less smoke. Sufficient funds are often not available, though.

Rachel Feinstein, government affairs manager at the industry trade group the Hearth, Patio and Barbecue Association, said the donations are going to communities in need where “the products that are in people’s homes are pretty much manufactured and installed before 1990 when the first EPA regulation for wood stoves came into effect.”

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said: “without this donation program, it is likely that these older, higher-emitting stoves would continue to operate and would not be changed out with [newer] appliances in the near future.”

The EPA in 2015 began to phase in standards to require new wood heaters, also called stoves, to burn more efficiently and create less smoke and soot that people inhale as particle pollution.

Breathing in those fine particles can worsen asthma and trigger heart attacks, stroke, irregular heart rhythms and heart failure, especially in people already at risk for these conditions, according to the EPA. Other pollutants from wood stoves are known carcinogens.

For the first five years, retailers could sell wood heaters that emitted no more than 4.5 grams per hour of particulate matter (PM). After that, the heaters would need to be even cleaner, emitting no more than 2 grams per hour of PM.

As a 15 May deadline to switch to cleaner heaters was approaching this year, businesses complained they hadn’t been able to sell all their older stoves, in part because of the coronavirus pandemic. The EPA declined to extend the deadline and instead agreed to a plan from the Hearth, Patio and Barbecue Association to set up the donation program. Companies donating the older stoves would be able to take tax deductions to offset their losses. Ahead of the deadline, 15 retailers donated 66 stoves.

But then the EPA reversed its position. On 15 May, the agency proposed to let retailers sell the older stoves through November – leaving further donations in limbo. the EPA said it would temporarily relax enforcement of the standard.

Environmental groups are opposing the extension, saying the industry has had plenty of time to sell its non-compliant stoves. They say the donation program could also be misguided, particularly because of the communities it targets.

“Five years was a very generous amount of time to make this transition. The industry has moved on – the leading manufacturers got there a long time ago,” said Timothy Ballo, a staff attorney for Earthjustice. “There’s no reason to reward manufacturers and retailers who decided to bank on the prospect of getting the extension.”

Ballo said it was not “a great option” to burden struggling communities with more pollution.

Tribal communities and indigenous Alaskans have “long experienced lower health status when compared to other Americans”, according to the Indian Health Service. That includes a lower life expectancy and disproportionate disease burden.

Appalachia also has higher mortality rates than the nation in seven leading causes of death, including heart disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), injury, stroke, diabetes and suicide, according to the Appalachian Regional Commission.

“I understand for a family that needs a source of heat, having that stove as an option through a donation program is probably better than nothing, but it is inflicting harm on their neighbors and that’s something you have to weigh as a countervailing concern,” Ballo said.

Public health experts warn the donations could force more pollution on already vulnerable populations amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Wood-burning devices emit pollutants known to make people sick, including fine particle pollution and chemicals like benzene, formaldehyde, acrolein and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

“What’s disappointing is there have been efforts to really find solutions that help these areas in need, understanding they are looking to reduce home-heating costs,” said Lisa Rector, policy director of a non-profit association of north-eastern air quality agencies.

“It’s especially concerning that in this time when we’re dealing with a pandemic that attacks the respiratory system that we’re not really carefully thinking through this.”

But the industry and the communities set to receive the heaters argue they will replace much worse alternatives that are in use.