TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

july 2024

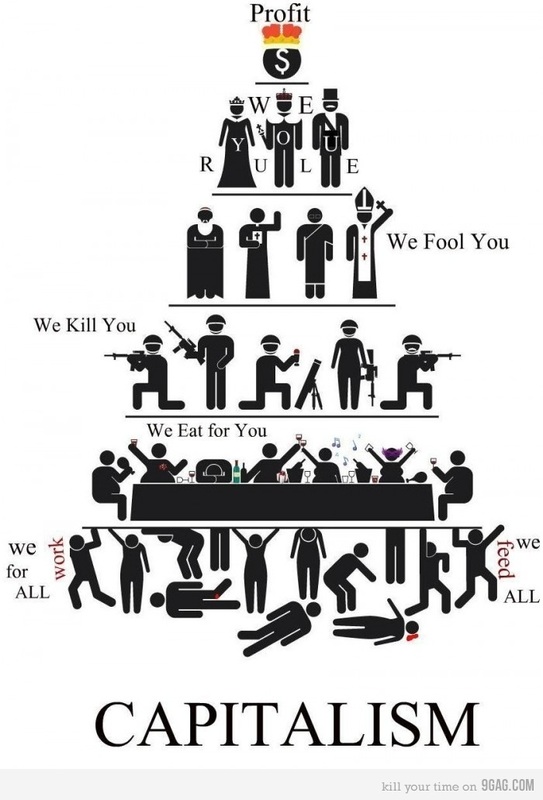

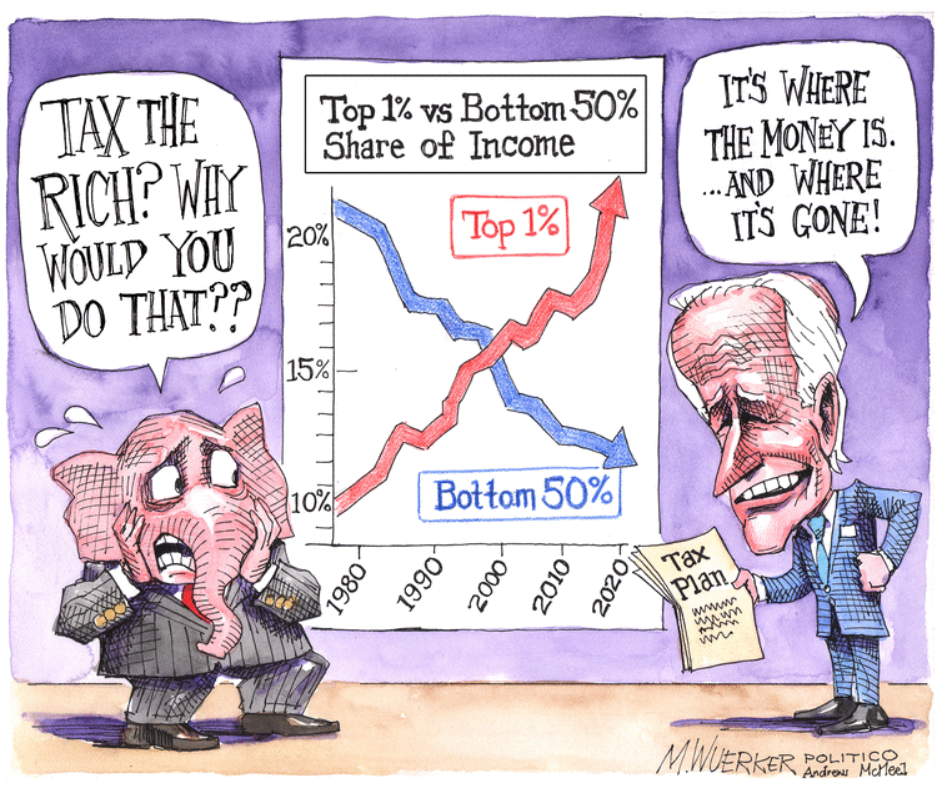

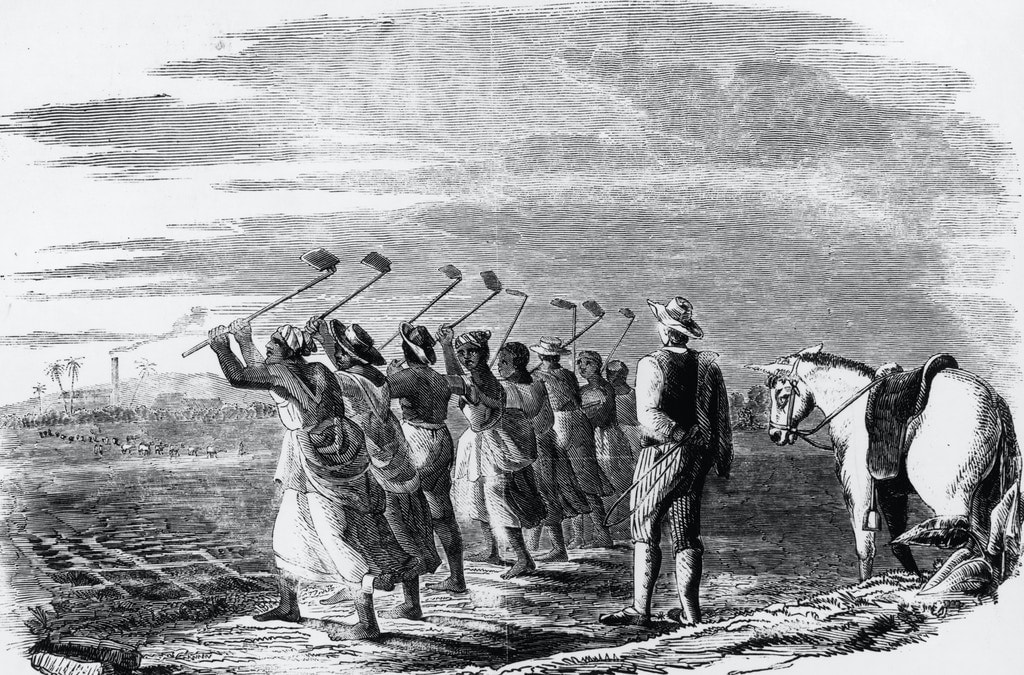

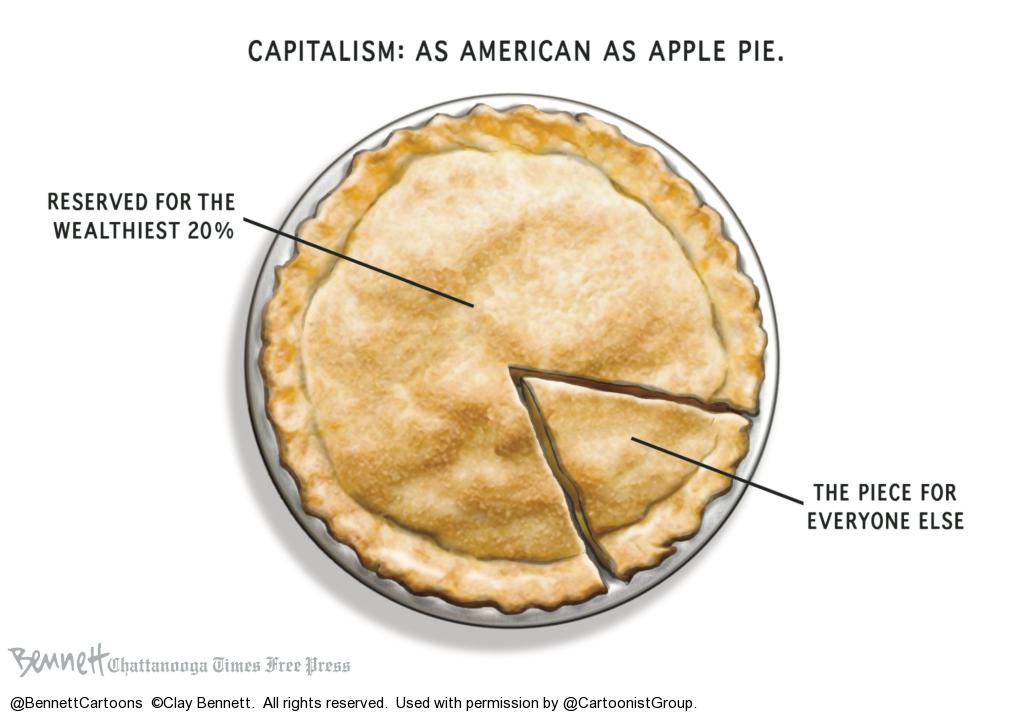

CAPITALISM REPRESENTED ITSELF AS FREEING SERFS, SLAVES, ETC. FREEDOM BECAME CAPITALISM'S SELF-CELEBRATION WHICH IT LARGELY REMAINS. YET THE REALITY OF CAPITALISM IS DIFFERENT FROM ITS CELEBRATORY SELF-IMAGE. THE MASS OF EMPLOYEES ARE NOT FREE INSIDE CAPITALIST ENTERPRISES TO PARTICIPATE IN THE DECISIONS THAT AFFECT THEIR LIVES (E.G., WHAT THE ENTERPRISE WILL PRODUCE, WHAT TECHNOLOGY IT WILL USE, WHERE PRODUCTION WILL OCCUR, AND WHAT WILL BE DONE WITH THE PROFIT WORKERS' EFFORTS HELP TO PRODUCE). IN THEIR EXCLUSION FROM SUCH DECISIONS, MODERN CAPITALISM'S EMPLOYEES RESEMBLE SLAVES AND SERFS. YES, PARLIAMENTS, UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE, ETC. HAVE ACCOMPANIED CAPITALISM - AN ADVANCE OVER SERFDOM AND SLAVERY. YET EVEN THAT ADVANCE HAS BEEN LARGELY UNDERMINED BY THE INFLUENCE OF THE HIGHLY UNEQUALLY DISTRIBUTED WEALTH AND INCOME THAT CAPITALISM HAS EVERYWHERE GENERATED.

RICHARD D. WOLFF

---------------------------------------------------------

The rapacity of contemporary capitalism is enabled by the weakness,

dishonesty, and cowardice of the flaccid and collaborationist left.

Luciana Bohne

--------------------------------------------------------

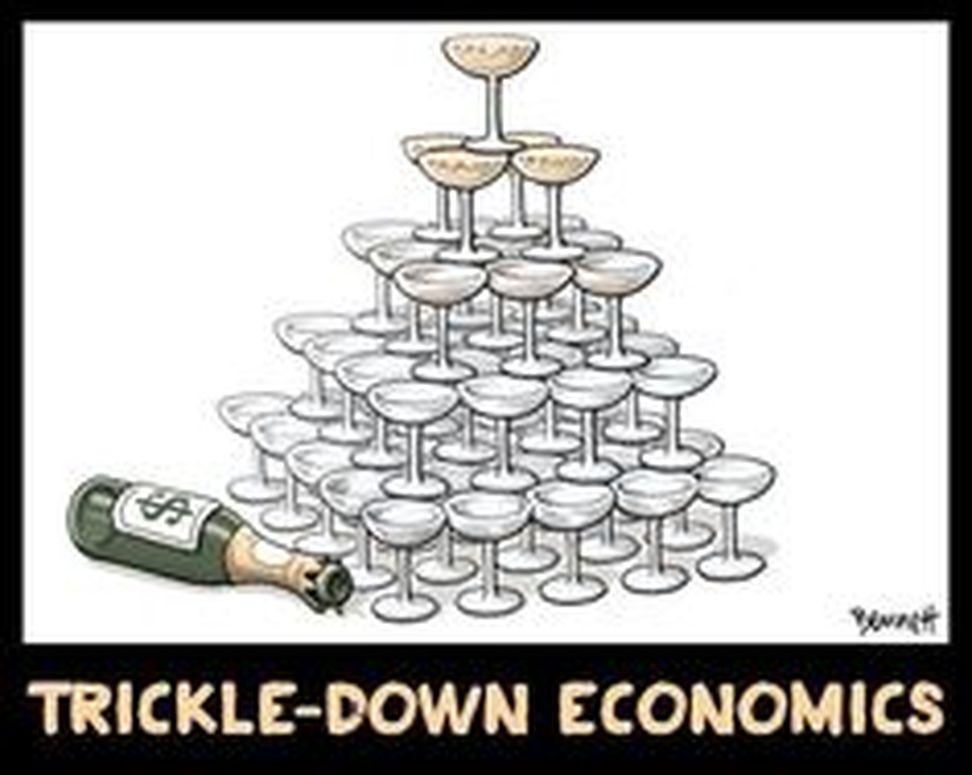

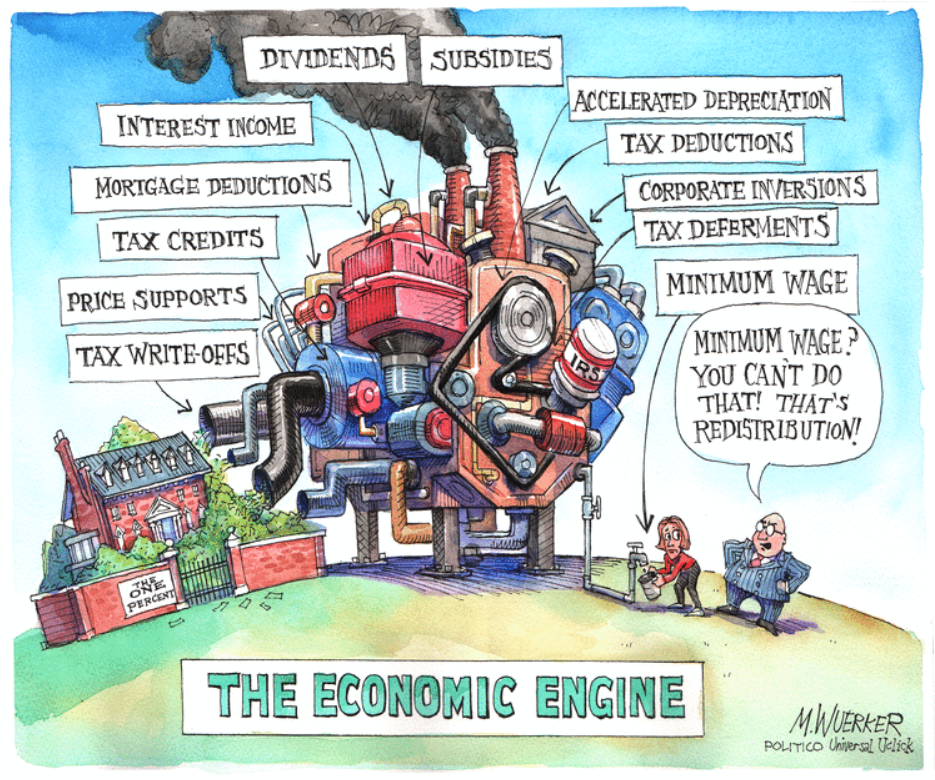

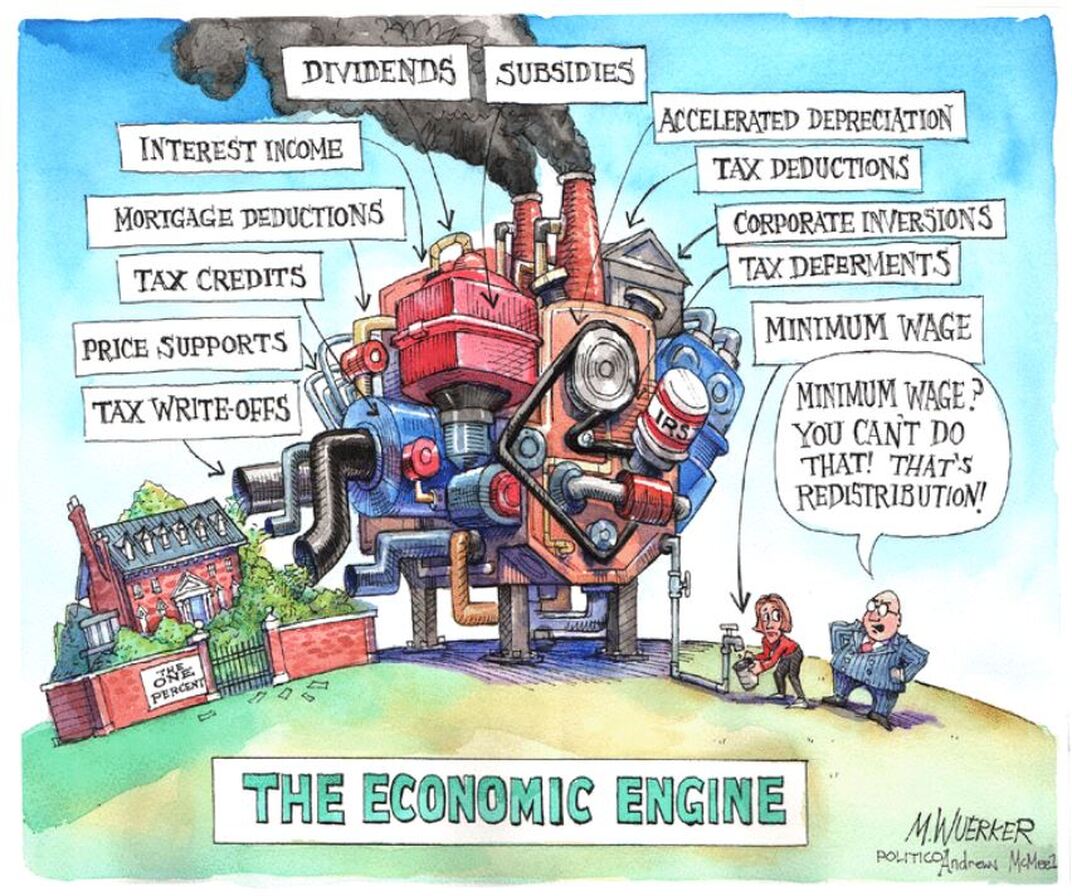

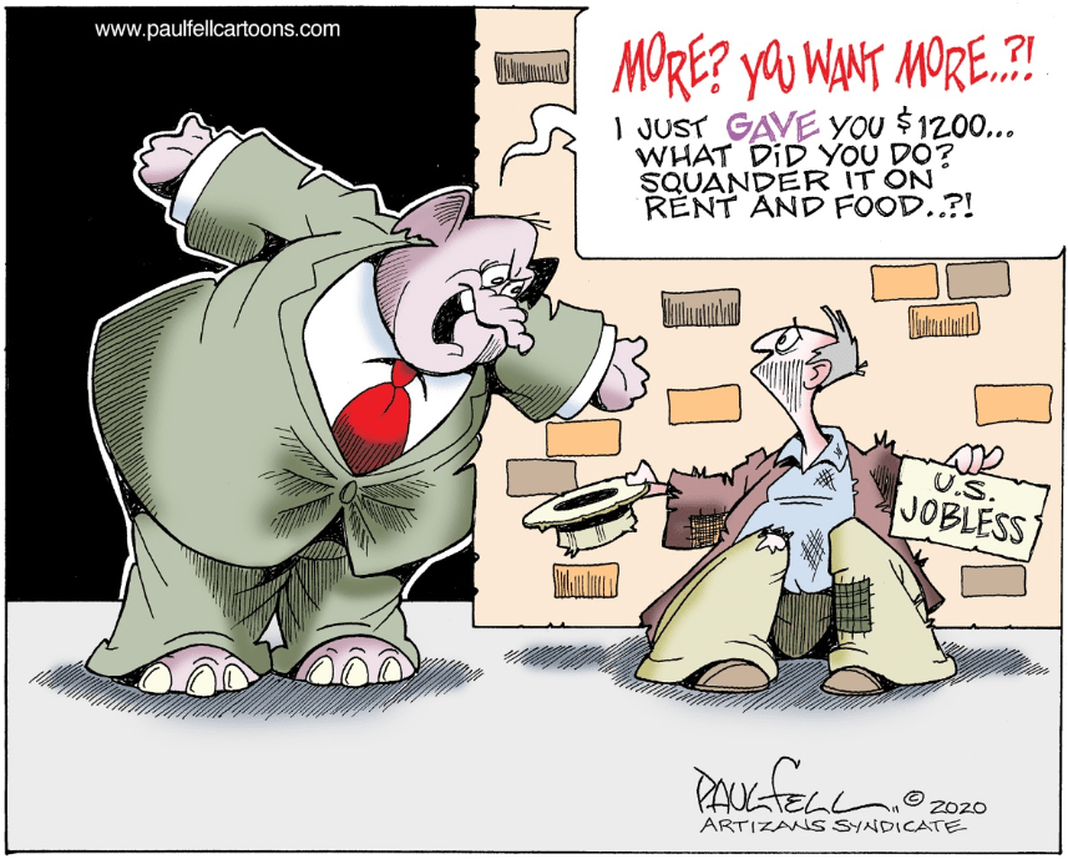

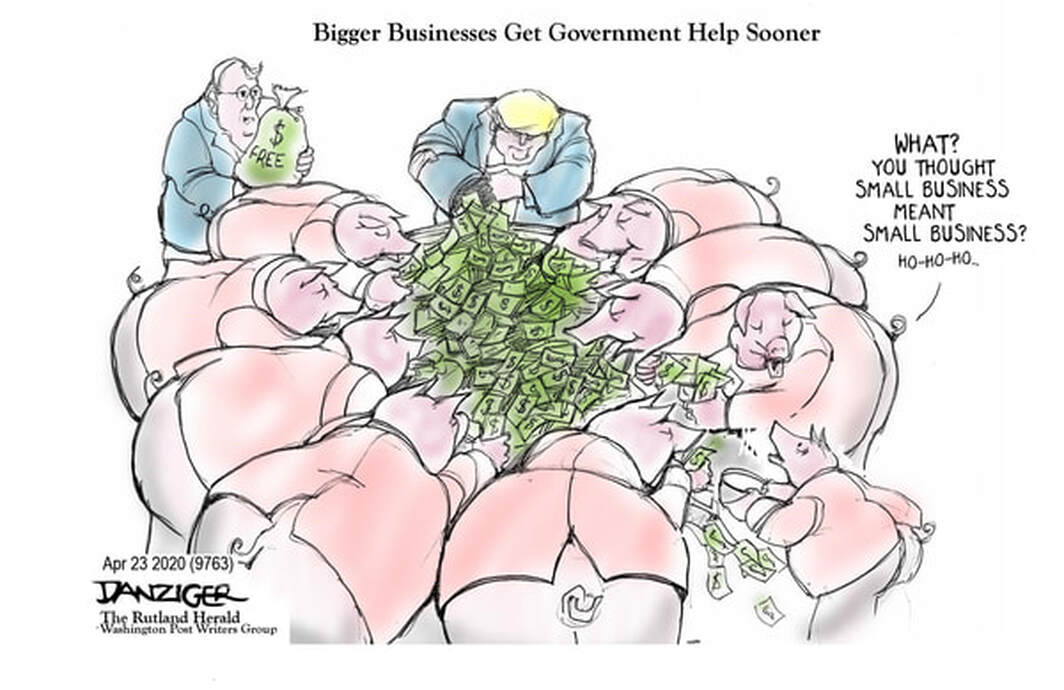

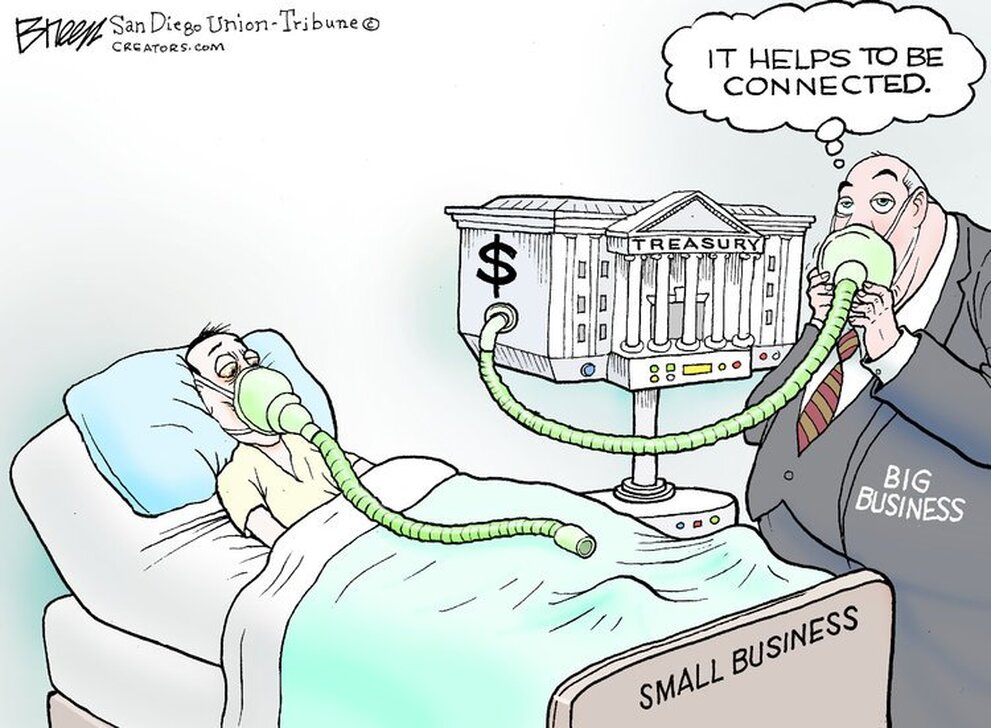

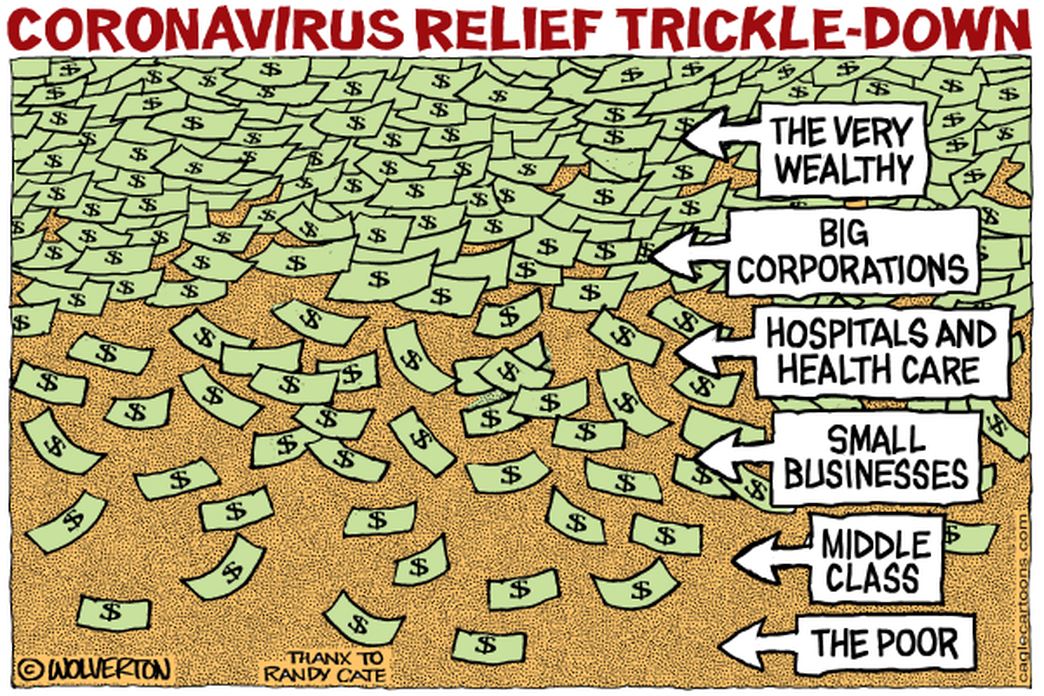

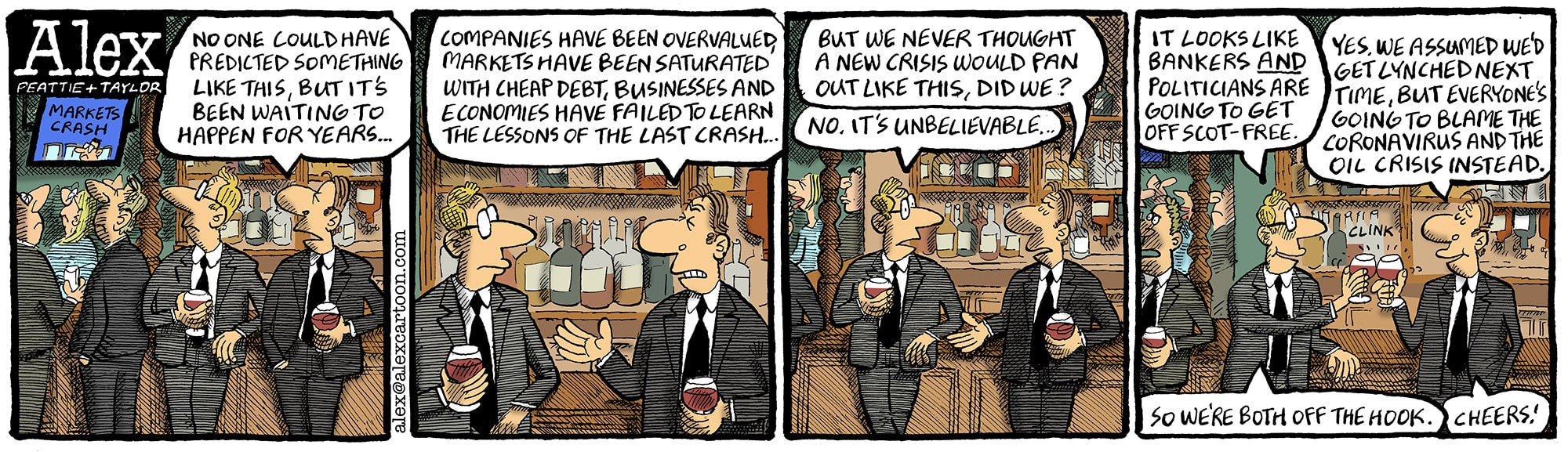

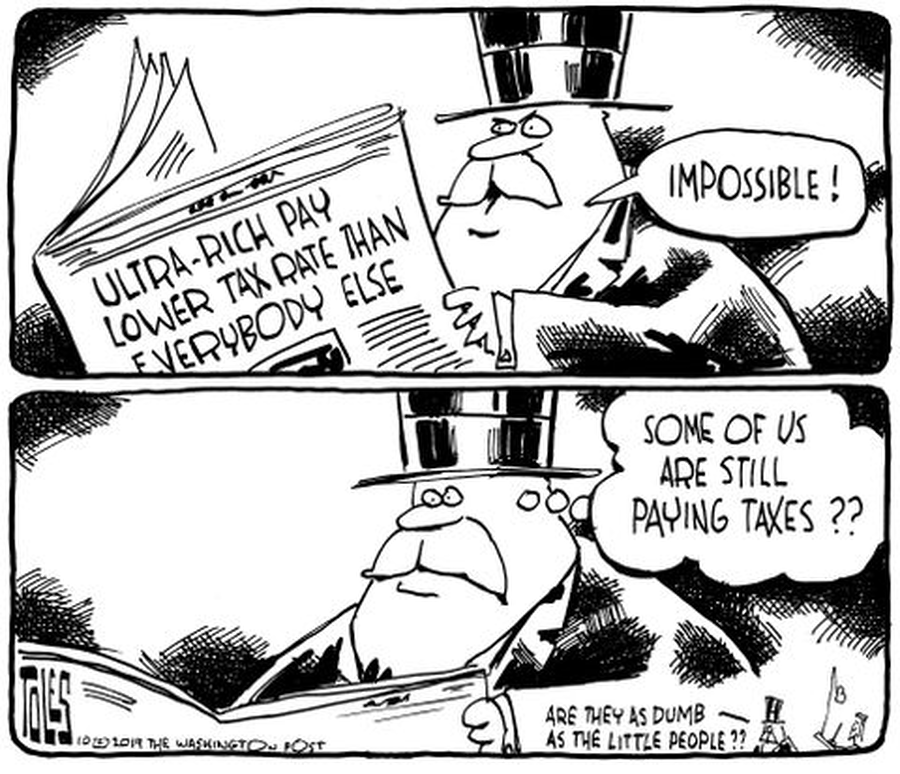

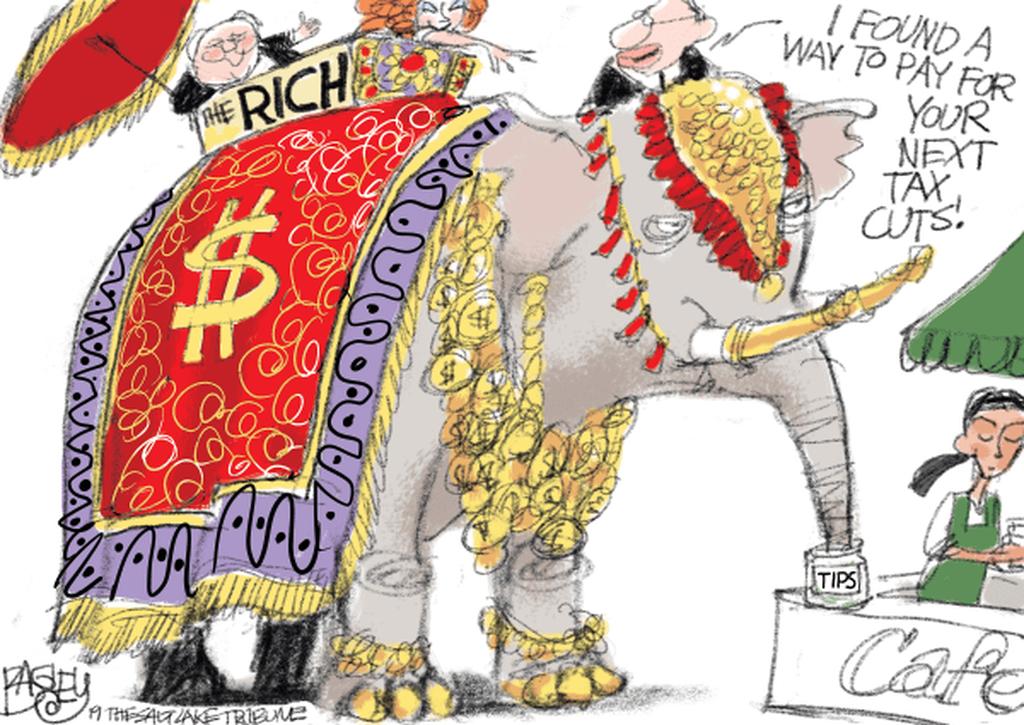

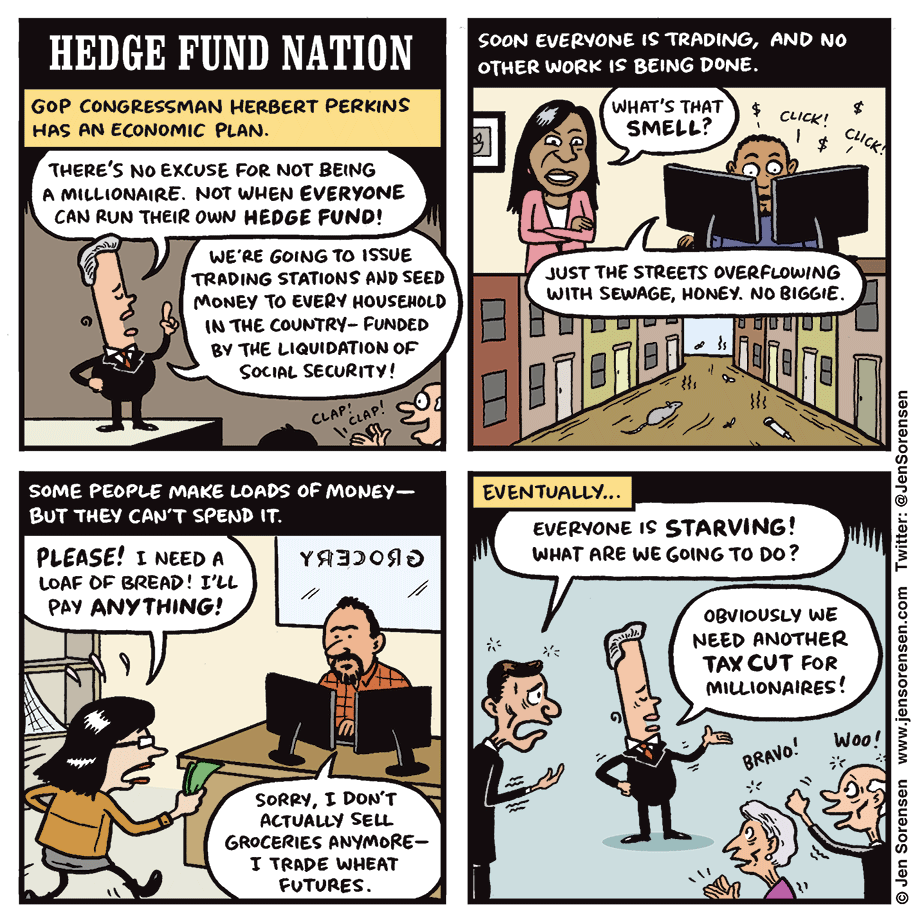

Socialism for the Rich, Capitalism for the Poor

Noam Chomsky: Consider this: Every time there is a crisis, the taxpayer is called on to bail out the banks and the major financial institutions. If you had a real capitalist economy in place, that would not be happening. Capitalists who made risky investments and failed would be wiped out. But the rich and powerful do not want a capitalist system. They want to be able to run the nanny state so when they are in trouble the taxpayer will bail them out. The conventional phrase is "too big to fail."

The IMF did an interesting study a few years ago on profits of the big US banks. It attributed most of them to the many advantages that come from the implicit government insurance policy -- not just the featured bailouts, but access to cheap credit and much else -- including things the IMF researchers didn't consider, like the incentive to undertake risky transactions, hence highly profitable in the short term, and if anything goes wrong, there's always the taxpayer. Bloomberg Businessweek estimated the implicit taxpayer subsidy at over $80 billion per year.

-----------------------------------------------

“As soon as you're born they make you feel small

By giving you no time instead of it all

'Til the pain is so big you feel nothing at all…

Keep you doped with religion, and sex, and T.V.

And you think you're so clever and classless and free

But you're still fucking peasants as far as I can see…”

— John Lennon, “Working Class Hero

The reason we have poverty is that we have no imagination. There are a great many people accumulating what they think is vast wealth, but it's only money... they don't know how to enjoy it, because they have no imagination.

alan watts

articles

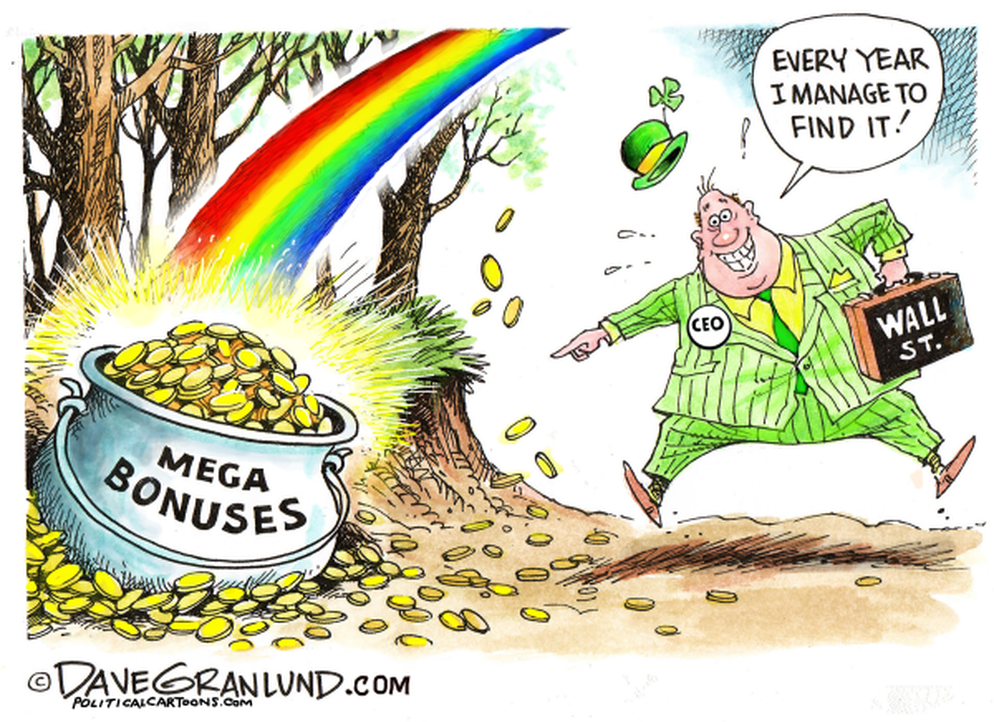

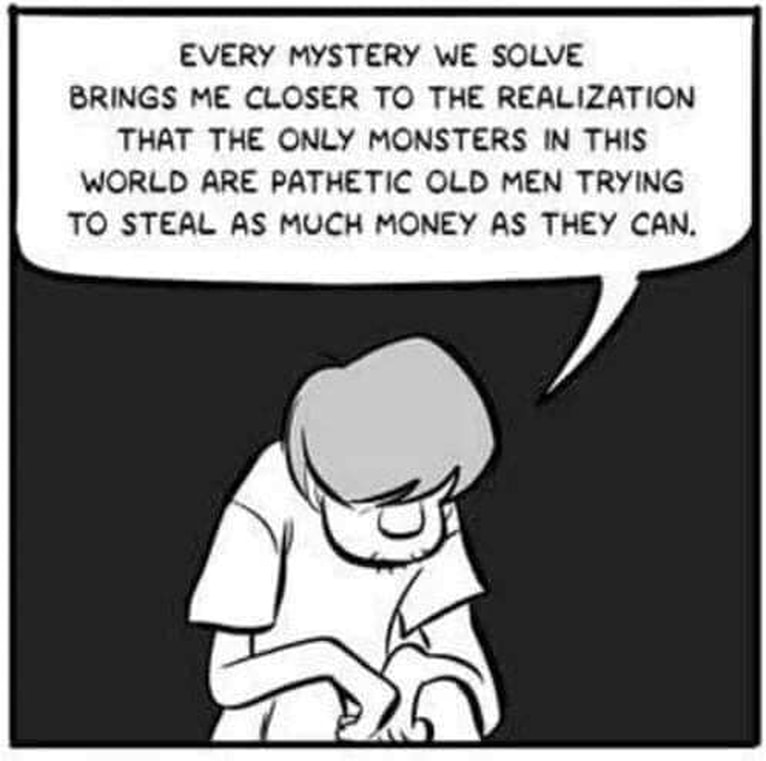

*REPORT: CEOS ARE DRIVING “GREEDFLATION,” RAISING PRICES TO PAY THEMSELVES MORE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CORPORATE PROFITS SOARED TO HIGHEST LEVELS IN 7 DECADES LAST YEAR

(ARTICLE BELOW)

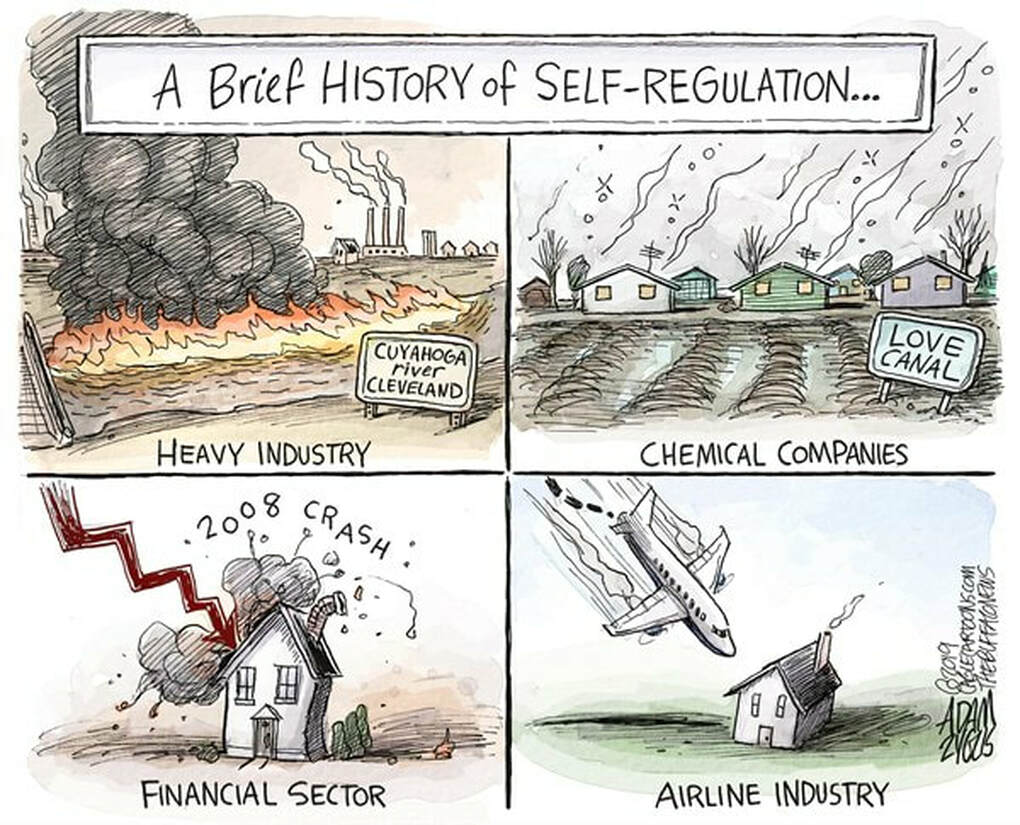

*BABY FORMULA INDUSTRY SUCCESSFULLY LOBBIED TO WEAKEN BACTERIA SAFETY TESTING STANDARDS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*FIRST QUARTER OF 2022 SEES RECORD $1 BILLION SPENT ON LOBBYING

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CORPORATE PROFITEERS BLAMED PRICE INCREASES ON LABOR COSTS — THEN GAVE BIG RAISES TO CEOS(ARTICLE BELOW)

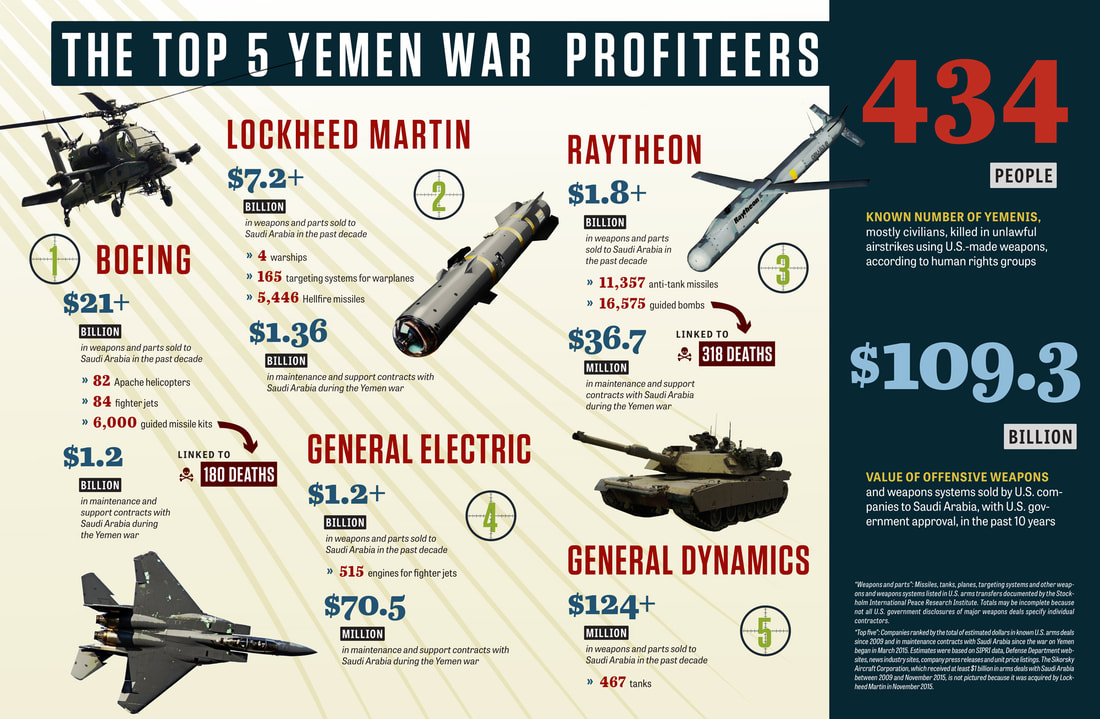

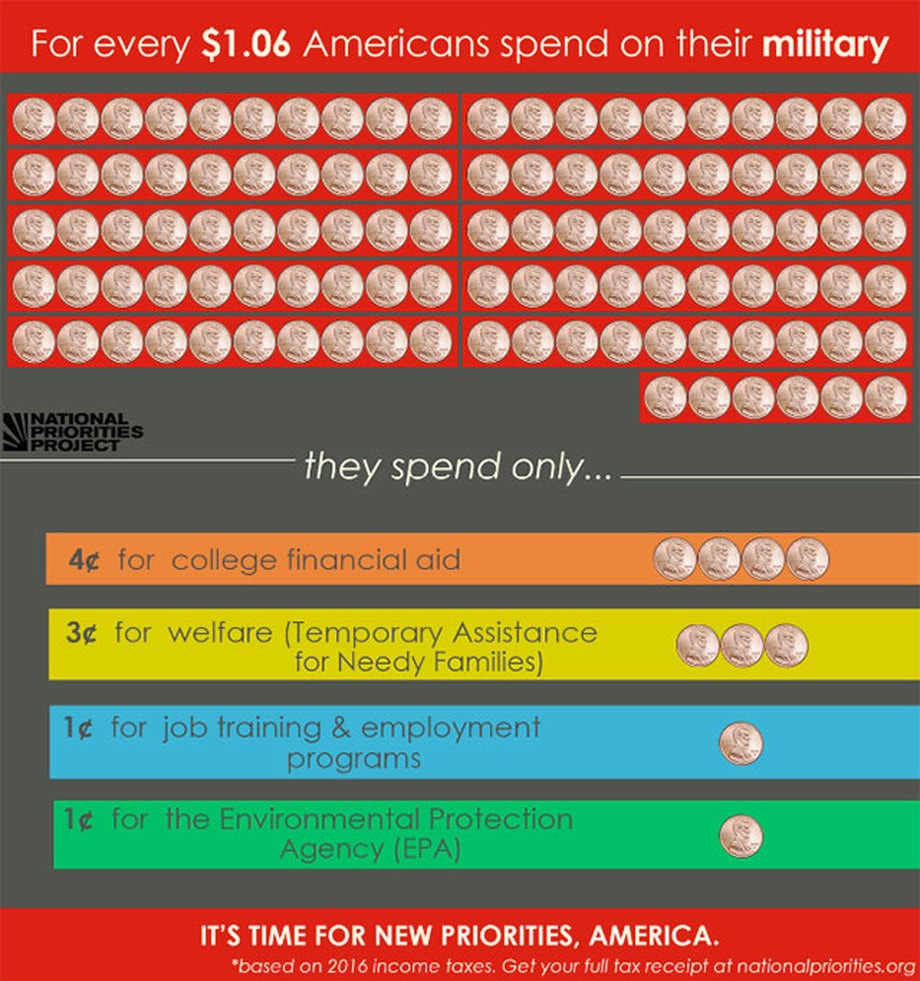

*AVERAGE US TAXPAYER GAVE $900 TO MILITARY CONTRACTORS LAST YEAR

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CORPORATIONS ARE SUPPRESSING WAGES. THERE’S AN EASY FIX FOR THAT.

(ARTICLE BELOW)

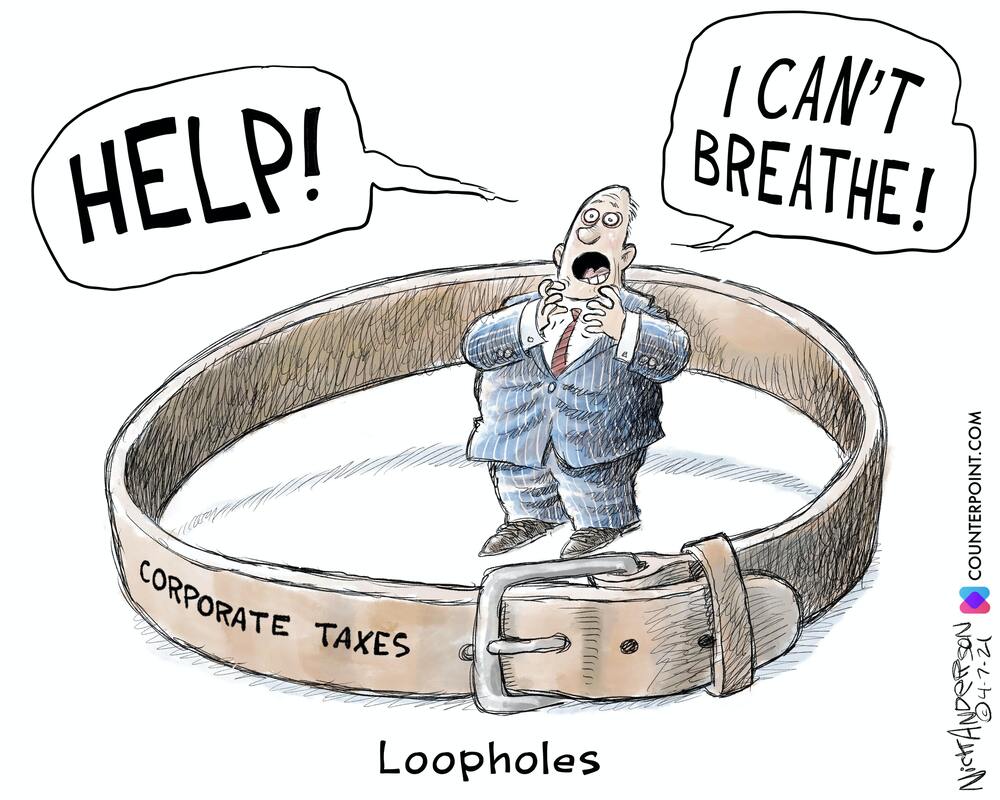

*AMAZON DODGED $5.2 BILLION IN TAXES LAST YEAR, REPORT FINDS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

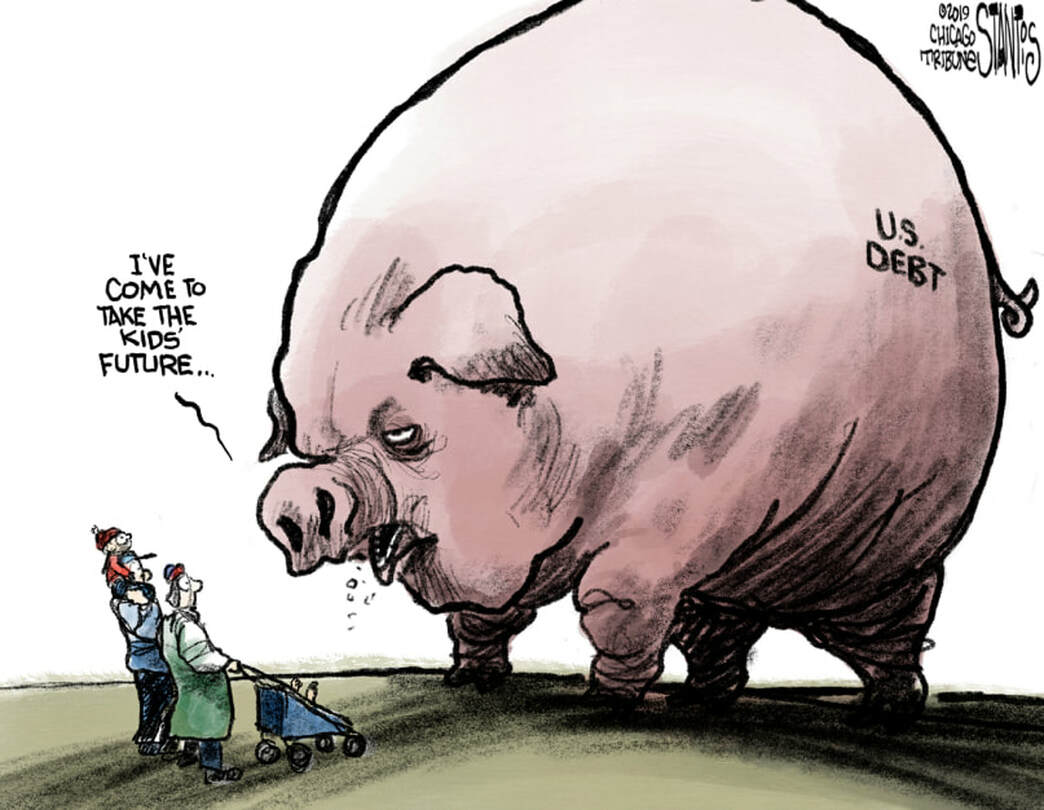

*US’S RICHEST FAMILIES SET TO DODGE $8.4 TRILLION IN TAXES OVER NEXT DECADES

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WYOMING REVEALED AS ONE OF WORLD'S TOP TAX HAVENS WITH 'COWBOY COCKTAIL' SCHEME TO HIDE MONEY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*MERCK SELLS FEDERALLY FINANCED COVID PILL TO U.S. FOR 40 TIMES WHAT IT COSTS TO MAKE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*TRASHING THE PLANET AND HIDING THE MONEY ISN’T A PERVERSION OF CAPITALISM. IT IS CAPITALISM(ARTICLE BELOW)

*MORE THAN HALF OF AMERICA’S 100 RICHEST PEOPLE EXPLOIT SPECIAL TRUSTS TO AVOID ESTATE TAXES(ARTICLE BELOW)

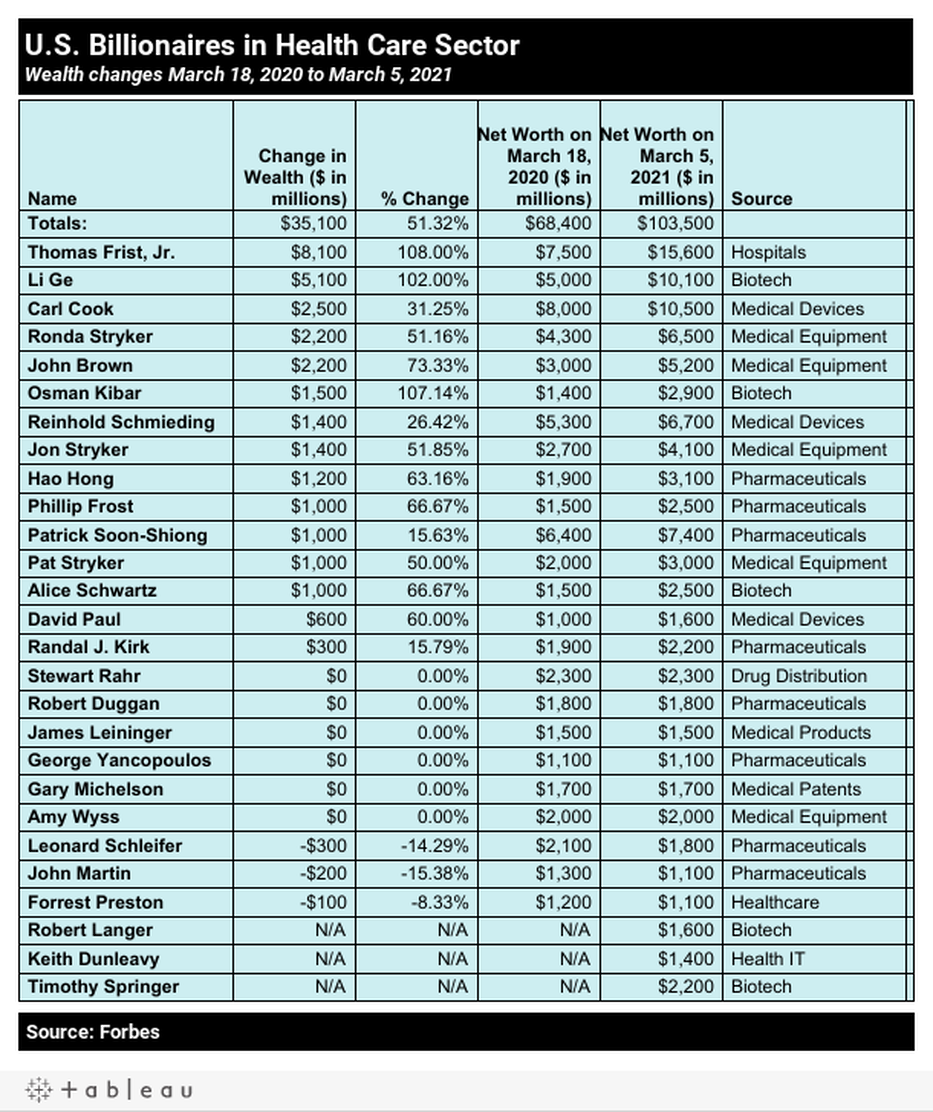

*PANDEMIC PROFITS: TOP US HEALTH INSURERS MAKE BILLIONS IN SECOND QUARTER

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*REPORT: REAL ESTATE GROUPS PAID GOP LAWMAKERS HUGE SUMS TO REINSTATE EVICTIONS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*DCREPORT UNCOVERS A HUGE SECRET TAX FAVOR FOR SUPER WEALTHY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*MICROSOFT IRISH SUBSIDIARY PAID ZERO CORPORATE TAX ON £220BN PROFIT LAST YEAR

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The Business Class Has Been Fearmongering About Worker Shortages for Centuries

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*HERE'S HOW MUCH BIG COMPANIES LIKE MCDONALD'S AND WALMART WOULD PAY UNDER SANDERS' AND WARREN'S TAX ON CEO PAY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*OWNERS OF HOSPITAL CONGLOMERATE MADE BILLIONS AS HEALTH CARE WORKERS LACKED PPE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE DAMNING TRUTH ABOUT CEO PAY HAS BEEN REVEALED BY THIS RESEARCH

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*RICH AMERICANS WHO FEAR HIGHER TAXES HURRY TO MOVE MONEY NOW

(ARTICLE BELOW)

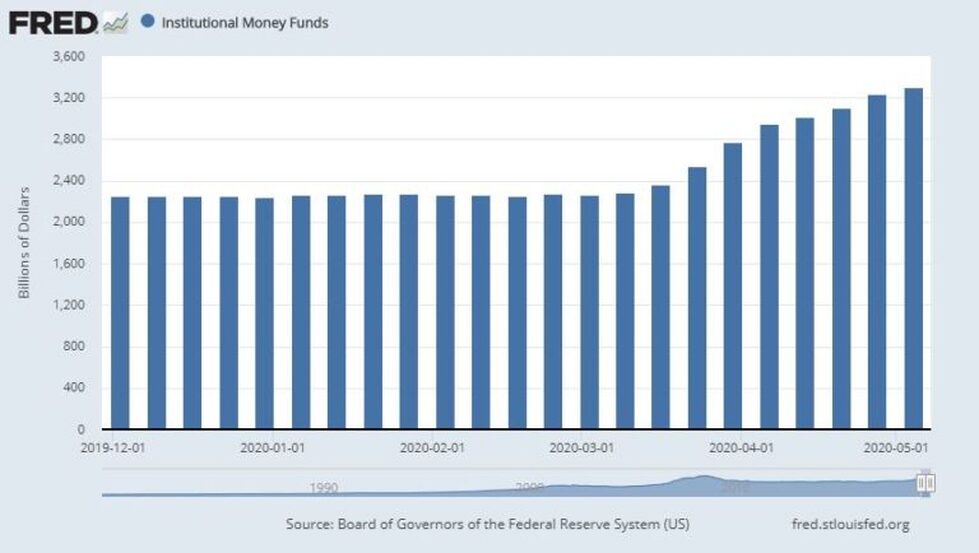

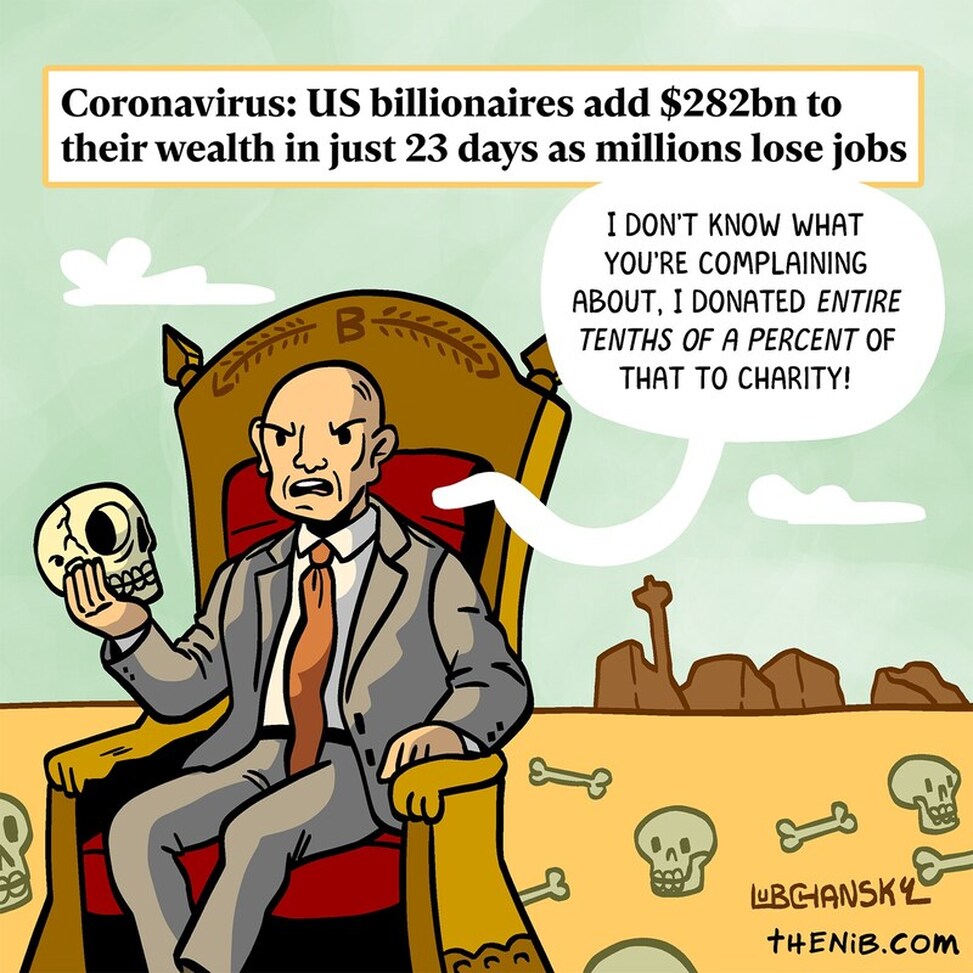

*NEW REPORT SHOWS TOP BILLIONAIRES’ WEALTH SKYROCKETING DURING PANDEMIC

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION ALLOWED AVIATION COMPANIES TO TAKE BAILOUT FUNDS AND LAY OFF WORKERS, SAYS HOUSE REPORT(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Capitalism Made Women of Color More Vulnerable to the COVID Recession

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Economist Richard Wolff: Capitalism is the reason COVID-19 is ravaging America

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*How the U.S. Chamber of Commerce wrecked the economy — and made the pandemic worse(ARTICLE BELOW)

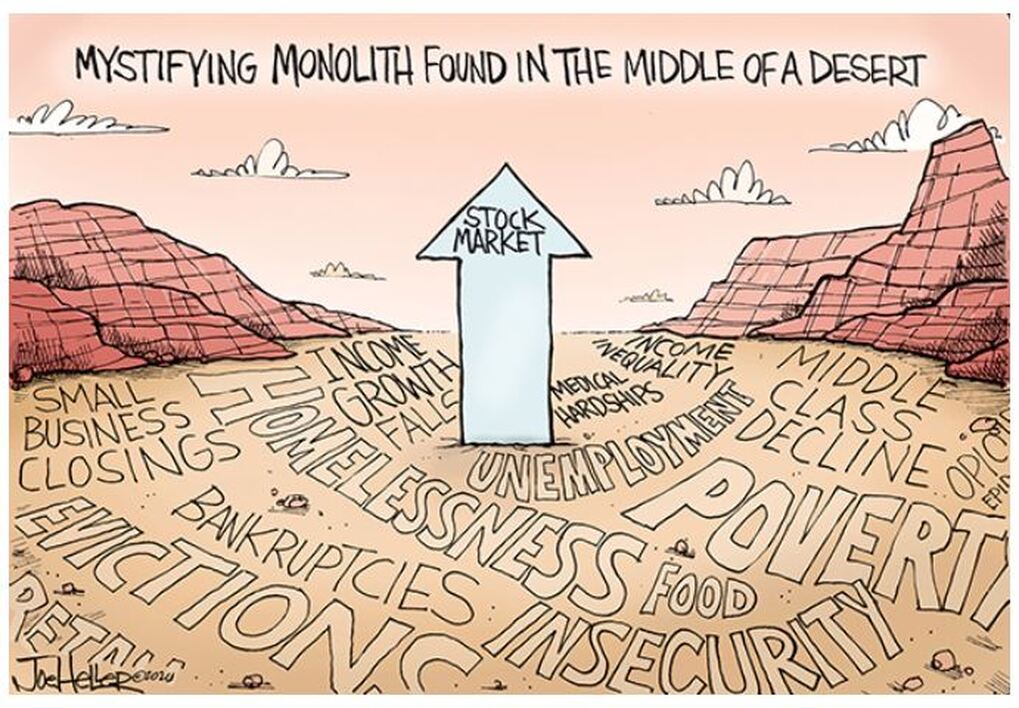

*As 45 million lost their jobs over the last three months, US billionaires grew $584 billion richer(ARTICLE BELOW)

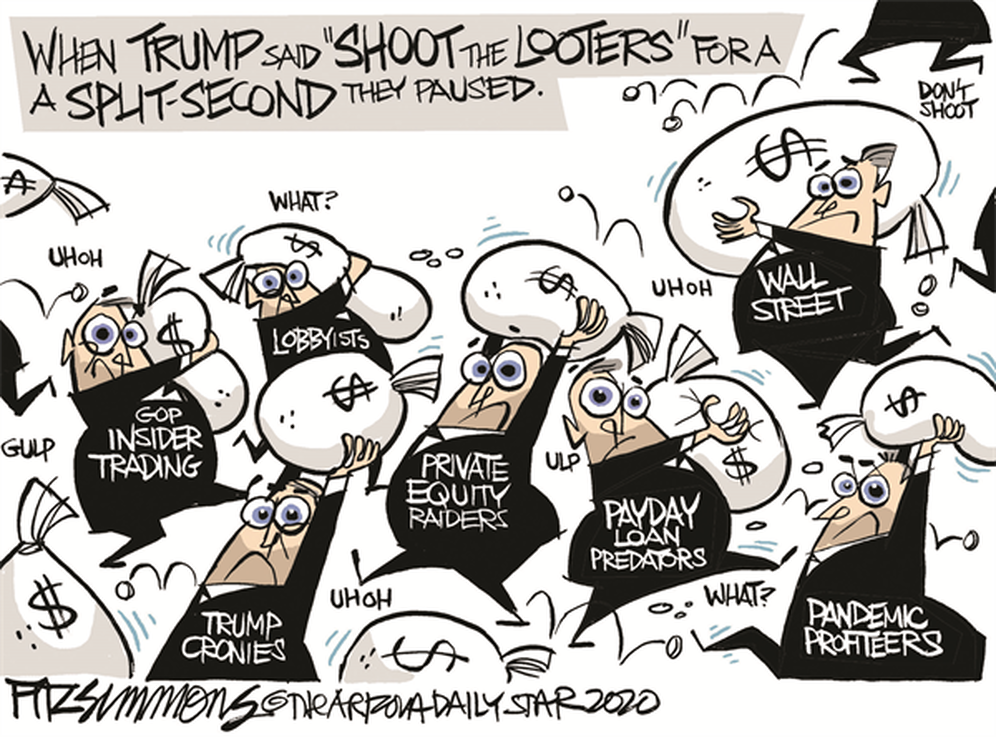

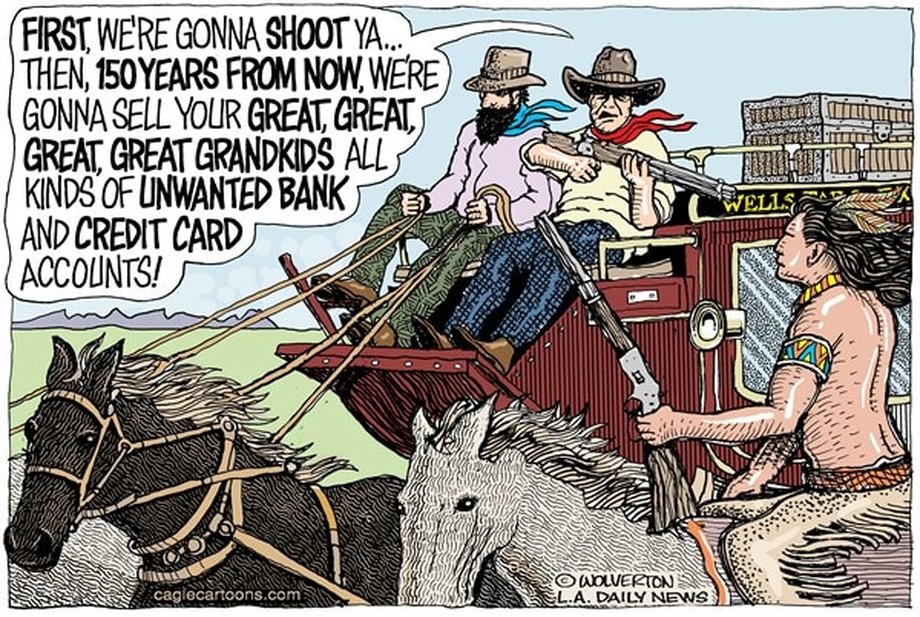

*FORGET “LOOTING.” CAPITALISM IS THE REAL ROBBERY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE NUMBERS ARE IN—THE TRUMP-RADICAL REPUBLICAN RESPONSE HAS BEEN GREAT FOR CORPORATIONS AND THE ONE-PERCENTERS, NOT SO GOOD FOR YOU(ARTICLE BELOW)

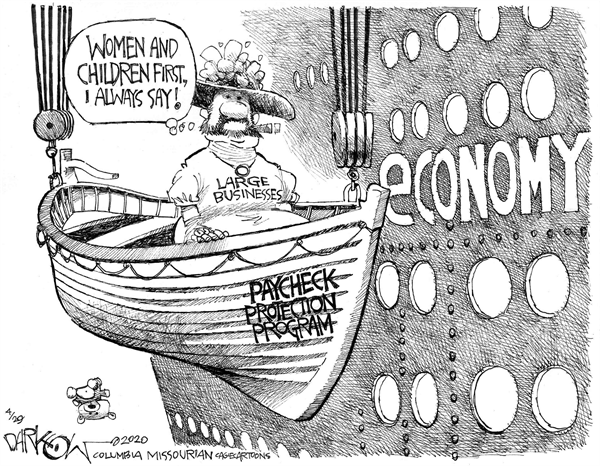

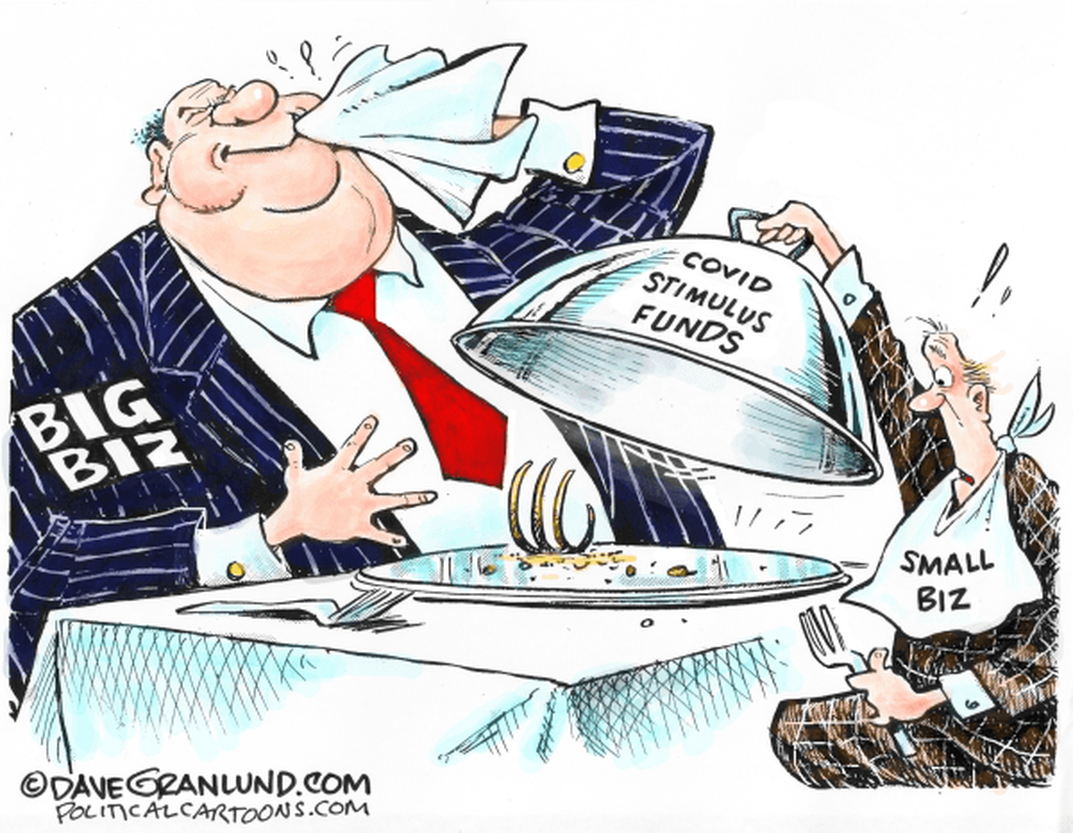

*The Bailout Is Working — For the Rich

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*TOP US COMPANIES LAY OFF THOUSANDS OF WORKERS WHILE REWARDING SHAREHOLDERS AMID CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Robert Reich breaks down the sham of corporate social responsibility

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*BIG COMPANIES THAT GAVE EXECUTIVES HUGE BONUSES, PAID MASSIVE FINES, CASH IN ON SMALL BUSINESS AID(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Bezos, Musk among billionaires gaining net worth in pandemic: report

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CASH-STRAPPED HOSPITALS LAY OFF THOUSANDS OF HEALTH WORKERS DESPITE COVID-19 STAFF SHORTAGES(ARTICLE BELOW)

*HOW THE FEDERAL RESERVE IS BAILING OUT BIG CORPORATIONS AND WALL STREET BANKS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*‘WHO CARES? LET ’EM GET WIPED OUT’: STUNNING CNBC ANCHOR, VENTURE CAPITALIST SAYS LET HEDGE FUNDS FAIL AND SAVE MAIN STREET(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Medical Staffing Companies Owned by Rich Investors Cut Doctor Pay and Now Want Bailout Money(ARTICLE BELOW)

*How Private-Equity Firms Squeeze Hospital Patients for Profits

(EXCERPT BELOW)

*U.S. companies criticized for cutting jobs rather than investor payouts

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ONE REASON CAREGIVERS ARE WEARING TRASH BAGS: A U.S. FIRM HAD TO RECALL 9 MILLION SURGICAL GOWNS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A PRIVATE EQUITY BARON SITTING ON AN EMPTY PHILADELPHIA HOSPITAL IS IN LINE FOR HUGE TAX GIFT IN THE COVID-19 STIMULUS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*AT LAST: TIME TO KILL "USELESS EATERS"

(EXCERPT BELOW)

*The Virus of Capitalism Has Infected the COVID-19 Fight

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Late-stage capitalism primed us for this pandemic

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*FILINGS SHOW TOP HEALTHCARE CEOS RAKED IN COMBINED $300 MILLION IN 2019

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*AT&T To Lay Off More Workers And Cut Costs By Tens Of Billions—Those Tax Breaks Are Working!(ARTICLE BELOW)

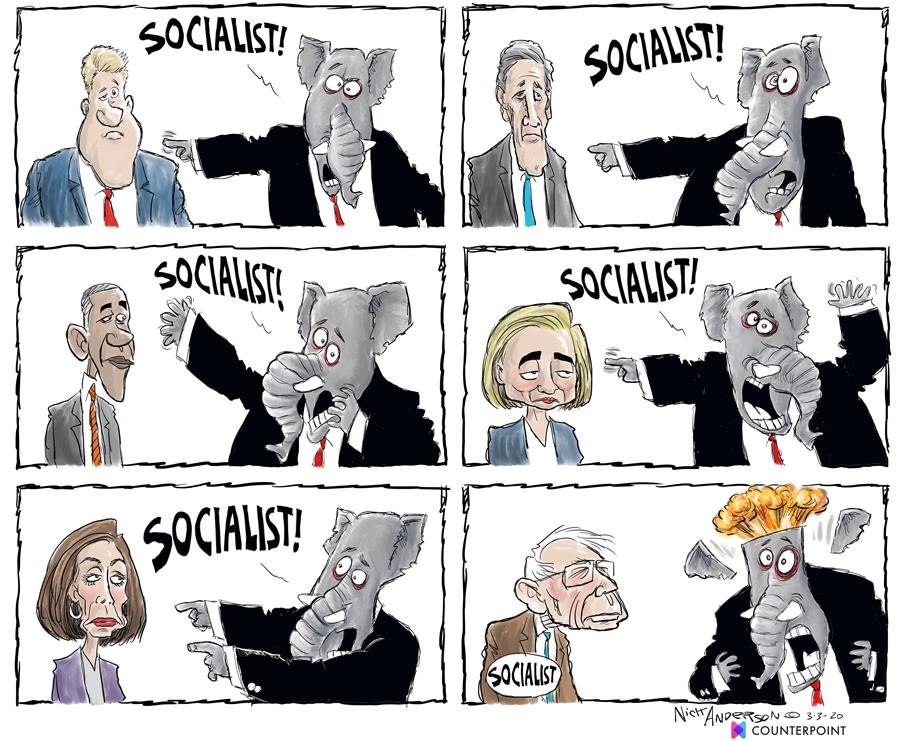

*The real global threat to 21st century freedom is authoritarian capitalism — not democratic socialism(ARTICLE BELOW)

*OPINION: THE DISASTER OF UTOPIAN ENGINEERING

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The monopolization of milk

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The plutocrats’ most effective secret weapon is the U.S. tax code

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*U.S. company directors compensated more than ever, but now risk backlash

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Neither Democrats Nor Republicans Will Admit the Problem Is Capitalism Itself

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Here’s why Capitalism vs Socialism is a false choice

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Here’s the big problem with American capitalism

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Capitalism Is Not the “Market System”

(ARTICLE BELOW)

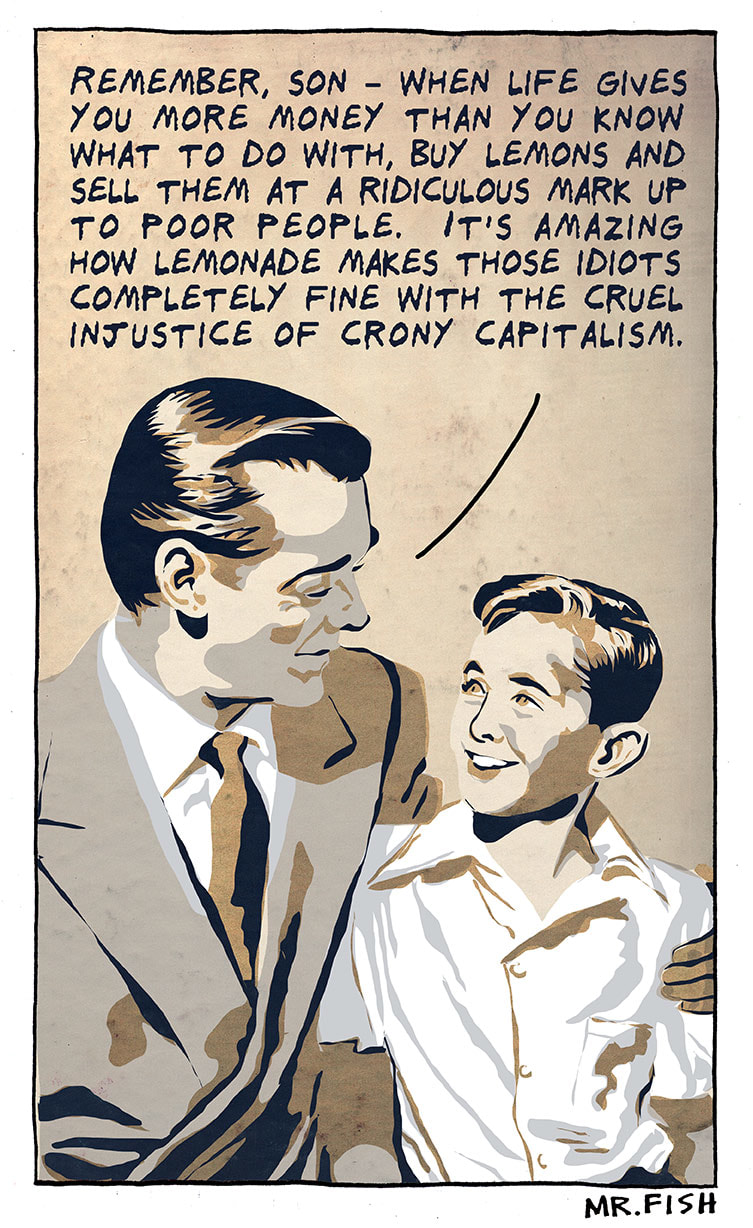

*The Normalization of Corruption

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*'Corporations Are People' Is Built on an Incredible 19th-Century Lie

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*5 BIG MYTHS SOLD BY THE DEFENDERS OF CAPITALISM(excerpt below)

*CAPITALISM: THE NIGHTMARE(excerpt below)

*funnies and charts(below)

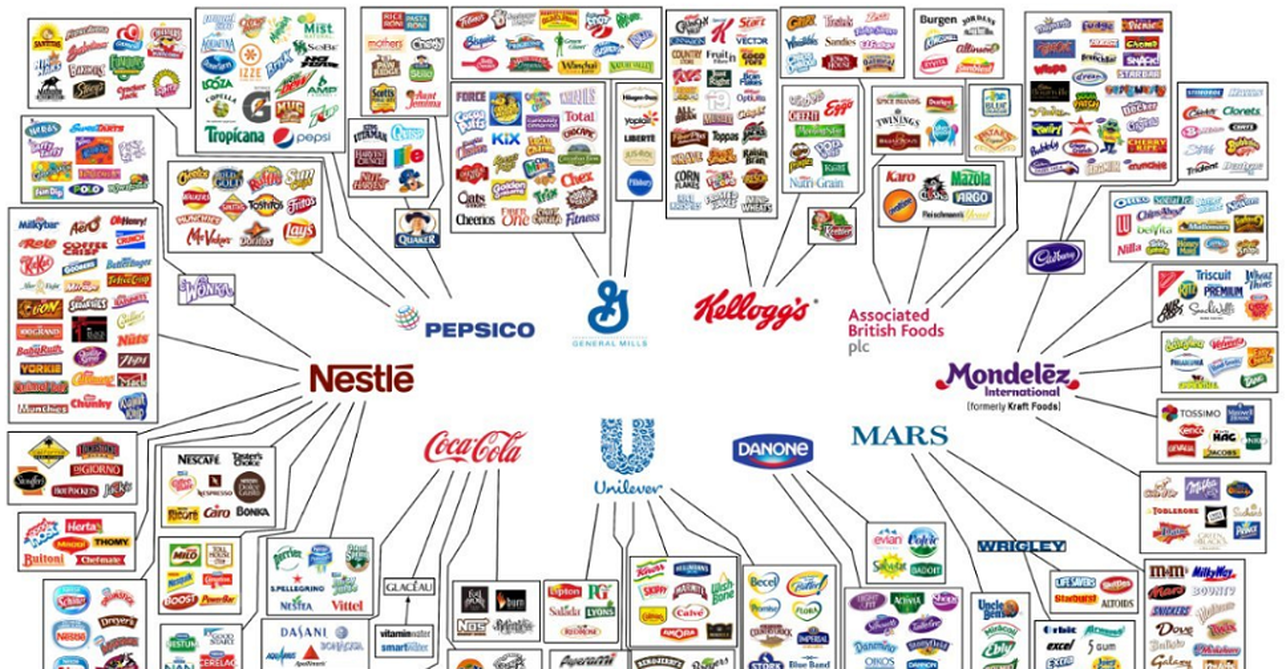

*THIS INFOGRAPHIC SHOWS HOW ONLY 10 COMPANIES CONTROL ALL THE WORLD’S BRANDS(ARTICLE BELOW)

The reality of capitalism

George Monbiot sums up well some of the more toxic elements of neoliberalism, which remained largely hidden since it was in the mainstream press less as an ideology than as an economic policy. He writes:

Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning. Attempts to limit competition are treated as inimical to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimized, public services should be privatized. The organization of labor and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone. Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

fundamentals of american capitalism

*american capitalists hate socialism until their incompetence and greed exposes their failure.

*a system created by slavery utilized on cotton plantations and have now become corporations.

*keep republicans in power to aide in ripping off american consumers

*always promote patriotism and american exceptionalism so the stupid public will think you are on their side

*nothing is more important than maximizing profits

*Never pass on opportunities to defraud CUSTOMERS

*when you get caught cheating on your taxes, make sure you have bribed enough government officials to minimize damage.

*maintain lobbyists, front groups, think tanks, etc. to lie and cover-up your corporate corruption.

*develop schemes to steal employee wages

*Maximize tax avoidance strategies

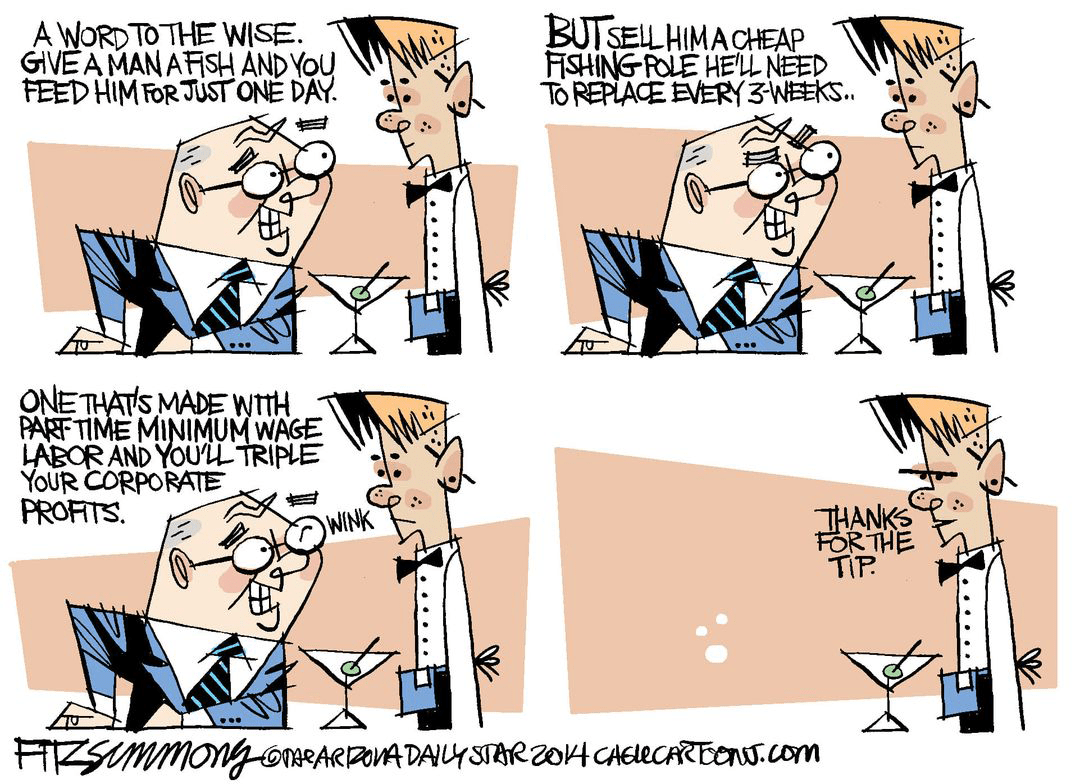

*hire part-time workers and deny them benefits

*always look to outsource labor to corrupt 3rd world countries to reduce labor costs

*sell mediocre products that never perform as advertised

*once your company is caught in scandal, mount an ad campaign portraying yourself as a wholesome organiZation

*never acknowledge guilt once your company is fined or sued

*hire lobbyist to bribe local politicians

*always scheme to avoid as many government regulations as possible

*make sure to defeat union organizing

*make sure that employees bare most of the cost of benefit packages

*underfund employees' pension plans

*make sure you can steal pension fund money through bankruptcy

*re-market and re-package old products as new and raise the price

GREED, IT ALL ABOUT GREED!!!

Report: CEOs Are Driving “Greedflation,” Raising Prices to Pay Themselves More

BY Jake Johnson, Common Dreams - TRUTHOUT

PUBLISHED July 19, 2022

The AFL-CIO’s latest annual analysis of top executive pay was published Monday with the following conclusion: “CEOs, not working people, are causing inflation.”

In recent months, corporate bosses and top Federal Reserve officials have pointed to workers’ wages as a factor in surging prices, which have pushed overall inflation in the United States to a four-decade high.

But the AFL-CIO’s new report attempts to reframe the national inflation discussion, emphasizing that while wage increases won by ordinary workers are drawing outsized attention from policymakers and executives, CEO pay hikes significantly outpaced the wage increases of rank-and-file employees last year.

Titled “Greedflation,” the report shows that “in 2021, CEOs of S&P 500 companies received, on average, $18.3 million in total compensation.”

“CEO pay rose 18.2%, faster than the U.S. inflation rate of 7.1%,” the analysis finds. “In contrast, U.S. workers’ wages fell behind inflation, with worker wages rising only 4.7% in 2021. The average S&P 500 company’s CEO-to-worker pay ratio was 324-to-1.”

The highest-paid executive among S&P 500 companies last year was Expedia’s Peter Kern, who brought in an eye-popping $296 million in total compensation.

Other executives at the top of the 2021 list were Amazon CEO Andy Jassy ($213 million), Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger ($179 million), Apple CEO Tim Cook ($99 million), and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon ($84 million).

“Runaway CEO pay is a symptom of greedflation — when companies increase prices to boost corporate profits and create windfall payouts for corporate CEOs,” the new analysis states.

During a conference call outlining the report’s findings, AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Fred Redmond said that “when you look at those numbers and at CEOs trying to blame workers for inflation, it just doesn’t add up.”

In his remarks during an earnings call earlier this year, for instance, Amazon’s chief financial officer attributed inflationary pressures felt within the company during the final quarter of 2021 to “wage increases and incentives in our operations.”

But Redmond pointed out that “last year, Amazon delivered the highest CEO-to-worker pay ratio in the S&P 500 Index with a pay ratio of 6,474 to 1.”

“Amazon’s new CEO Andy Jassy received $212.7 million in total compensation,” he noted. “What did Amazon’s median worker earn last year? Just $32,855… Corporate profits and runaway CEO pay are responsible for causing inflation, not workers’ wages.”

In a blog post on Monday, economist Dean Baker similarly argued that soaring executive pay is contributing to inflation, which has eroded modest wage gains that many ordinary workers have seen since late 2020.

“We… transfer tens of billions of dollars upward to CEOs and other top corporate executives through the corrupt corporate governance structure that we have instituted,” writes Baker, a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “In this context, it is not surprising that even mediocre CEOs can get paychecks in the tens of millions of dollars annually. And, it is not just the CEO. If the CEO gets $20 million, the chief financial officer might get $10 to $12 million, and even third-tier executives may get $2 to $3 million.”

“This is all inflationary,” he added.

The AFL-CIO’s analysis was released as the Federal Reserve gears up to hike interest rates by another 75 basis points at its upcoming policy meeting, a move that economists fear could push the U.S. economy closer to recession.

The second consecutive 0.75 percentage point rate hike is expected despite evidence that key divers of inflation — such as gas prices — are cooling. Wage growth has also slowed substantially in recent months, prompting experts to warn that additional rate increases could slash wages by driving up the unemployment rate — a potential disaster for millions.

“Higher unemployment lowers wage growth much more reliably and by larger amounts than it lowers inflation,” notes Josh Bivens, director of research at the Economic Policy Institute, noted last week. “Currently, wage growth is decelerating. This means there is no genuine need for a recession to pull wage growth down to sustainable levels.”

The AFL-CIO’s Redmond echoed that sentiment Monday, declaring that “we need to raise wages to help working people cope with rising prices, not make working people poorer by causing a recession.”

In recent months, corporate bosses and top Federal Reserve officials have pointed to workers’ wages as a factor in surging prices, which have pushed overall inflation in the United States to a four-decade high.

But the AFL-CIO’s new report attempts to reframe the national inflation discussion, emphasizing that while wage increases won by ordinary workers are drawing outsized attention from policymakers and executives, CEO pay hikes significantly outpaced the wage increases of rank-and-file employees last year.

Titled “Greedflation,” the report shows that “in 2021, CEOs of S&P 500 companies received, on average, $18.3 million in total compensation.”

“CEO pay rose 18.2%, faster than the U.S. inflation rate of 7.1%,” the analysis finds. “In contrast, U.S. workers’ wages fell behind inflation, with worker wages rising only 4.7% in 2021. The average S&P 500 company’s CEO-to-worker pay ratio was 324-to-1.”

The highest-paid executive among S&P 500 companies last year was Expedia’s Peter Kern, who brought in an eye-popping $296 million in total compensation.

Other executives at the top of the 2021 list were Amazon CEO Andy Jassy ($213 million), Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger ($179 million), Apple CEO Tim Cook ($99 million), and JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon ($84 million).

“Runaway CEO pay is a symptom of greedflation — when companies increase prices to boost corporate profits and create windfall payouts for corporate CEOs,” the new analysis states.

During a conference call outlining the report’s findings, AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer Fred Redmond said that “when you look at those numbers and at CEOs trying to blame workers for inflation, it just doesn’t add up.”

In his remarks during an earnings call earlier this year, for instance, Amazon’s chief financial officer attributed inflationary pressures felt within the company during the final quarter of 2021 to “wage increases and incentives in our operations.”

But Redmond pointed out that “last year, Amazon delivered the highest CEO-to-worker pay ratio in the S&P 500 Index with a pay ratio of 6,474 to 1.”

“Amazon’s new CEO Andy Jassy received $212.7 million in total compensation,” he noted. “What did Amazon’s median worker earn last year? Just $32,855… Corporate profits and runaway CEO pay are responsible for causing inflation, not workers’ wages.”

In a blog post on Monday, economist Dean Baker similarly argued that soaring executive pay is contributing to inflation, which has eroded modest wage gains that many ordinary workers have seen since late 2020.

“We… transfer tens of billions of dollars upward to CEOs and other top corporate executives through the corrupt corporate governance structure that we have instituted,” writes Baker, a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “In this context, it is not surprising that even mediocre CEOs can get paychecks in the tens of millions of dollars annually. And, it is not just the CEO. If the CEO gets $20 million, the chief financial officer might get $10 to $12 million, and even third-tier executives may get $2 to $3 million.”

“This is all inflationary,” he added.

The AFL-CIO’s analysis was released as the Federal Reserve gears up to hike interest rates by another 75 basis points at its upcoming policy meeting, a move that economists fear could push the U.S. economy closer to recession.

The second consecutive 0.75 percentage point rate hike is expected despite evidence that key divers of inflation — such as gas prices — are cooling. Wage growth has also slowed substantially in recent months, prompting experts to warn that additional rate increases could slash wages by driving up the unemployment rate — a potential disaster for millions.

“Higher unemployment lowers wage growth much more reliably and by larger amounts than it lowers inflation,” notes Josh Bivens, director of research at the Economic Policy Institute, noted last week. “Currently, wage growth is decelerating. This means there is no genuine need for a recession to pull wage growth down to sustainable levels.”

The AFL-CIO’s Redmond echoed that sentiment Monday, declaring that “we need to raise wages to help working people cope with rising prices, not make working people poorer by causing a recession.”

Corporate Profits Soared to Highest Levels in 7 Decades Last Year

BY Jake Johnson, Common Dreams - truthout

PUBLISHED June 21, 2022

A new paper published Tuesday shows that U.S. corporate price markups and profits surged to their highest levels since the 1950s last year, bolstering arguments for an excess profits tax as a way to rein in sky-high inflation.

Authored by Mike Konczal and Niko Lusiani of the Roosevelt Institute, the analysis finds that markups—the difference between the actual cost of a good or service and the selling price—”were both the highest level on record and the largest one-year increase” in 2021.

“Markups this high mean there is room for reversing them with little economic harm and likely societal benefit,” Konczal said in a statement. “To tackle inflation, we need an all-of-the-above administrative and legislative approach that includes demand, supply, and market power interventions.”

In their new brief, Konczal and Lusiani note that higher markups don’t always mean larger profits.

“But they did in 2021,” the researchers write, showing that the net profit margins of U.S. firms jumped from an annual average of 5.5% between 1960 and 1980 to 9.5% in 2021 as companies pushed up prices, citing inflationary pressures across the global economy as their justification.

“How high companies can increase their sales up and above their costs… matters for the economy more generally because these markups distribute economic gains from workers and consumers to firms and shareholders,” said Lusiani. “This is especially the case when almost 100% of these firms’ earnings derived from markups are distributed upward to shareholders rather than retained and reinvested.”

“Making corporations once again price-takers rather than price-makers,” Lusiani added, “will help bring down prices, and in time lead to a more equitable, innovative economy.”

The new research comes as the White House struggles to formulate a coherent and effective response to an inflation surge that has become a serious economic and political problem, particularly as the pivotal 2022 midterms approach.

Survey data shows that U.S. voters, including those in key battleground states, overwhelmingly want the Biden administration to challenge corporate power and support a windfall profits tax to counter soaring prices at grocery stores, gas stations, and elsewhere across the economy.

Konczal and Lusiani’s brief makes the case for a new tax to combat excess profits that they say have become “widespread.” Such a tax, the researchers argue, would help redistribute “runaway economic gains while simultaneously eroding company incentives to increase their markups.”

Additionally, they write, “increasing competition and reducing market power” through antitrust action “would bring down inflation to some degree, no matter its cause.”

But influential U.S. economists — former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers chief among them — have argued that solving high inflation would require pushing down wages and throwing millions of people out of work.

“We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment,” Summers, who spoke with President Joe Biden by phone Monday morning, said in an address in London later that same day.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who is leading an effort to tamp down inflation by aggressively hiking interest rates, has also cited modest wage increases over the past two years as a factor behind rising inflation, expressing his desire to “get wages down” despite evidence that wage growth has slowed in recent months.

Konczal and Lusiani contend in their paper that “while the idea that we are facing the threat of a wage-price spiral is becoming conventional wisdom, this brief and other research finds that changes to labor and worker compensation are not driving factors in recent markups.”

“If margins are unusually high, then there’s the possibility that profits and markups can decrease as either supply opens up or demand cools, removing pricing pressure,” they write. “Such a high profit margin also means that there’s room for wages to increase without necessarily raising prices — an important dynamic in a hot labor market.”

RELATED: Don’t Let Corporations Profit From Our Inflation PainCorporations are blaming rising prices on elected officials and worker organizing even as they rake in record profits.

by Brooke Adams, Truthout

Authored by Mike Konczal and Niko Lusiani of the Roosevelt Institute, the analysis finds that markups—the difference between the actual cost of a good or service and the selling price—”were both the highest level on record and the largest one-year increase” in 2021.

“Markups this high mean there is room for reversing them with little economic harm and likely societal benefit,” Konczal said in a statement. “To tackle inflation, we need an all-of-the-above administrative and legislative approach that includes demand, supply, and market power interventions.”

In their new brief, Konczal and Lusiani note that higher markups don’t always mean larger profits.

“But they did in 2021,” the researchers write, showing that the net profit margins of U.S. firms jumped from an annual average of 5.5% between 1960 and 1980 to 9.5% in 2021 as companies pushed up prices, citing inflationary pressures across the global economy as their justification.

“How high companies can increase their sales up and above their costs… matters for the economy more generally because these markups distribute economic gains from workers and consumers to firms and shareholders,” said Lusiani. “This is especially the case when almost 100% of these firms’ earnings derived from markups are distributed upward to shareholders rather than retained and reinvested.”

“Making corporations once again price-takers rather than price-makers,” Lusiani added, “will help bring down prices, and in time lead to a more equitable, innovative economy.”

The new research comes as the White House struggles to formulate a coherent and effective response to an inflation surge that has become a serious economic and political problem, particularly as the pivotal 2022 midterms approach.

Survey data shows that U.S. voters, including those in key battleground states, overwhelmingly want the Biden administration to challenge corporate power and support a windfall profits tax to counter soaring prices at grocery stores, gas stations, and elsewhere across the economy.

Konczal and Lusiani’s brief makes the case for a new tax to combat excess profits that they say have become “widespread.” Such a tax, the researchers argue, would help redistribute “runaway economic gains while simultaneously eroding company incentives to increase their markups.”

Additionally, they write, “increasing competition and reducing market power” through antitrust action “would bring down inflation to some degree, no matter its cause.”

But influential U.S. economists — former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers chief among them — have argued that solving high inflation would require pushing down wages and throwing millions of people out of work.

“We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment,” Summers, who spoke with President Joe Biden by phone Monday morning, said in an address in London later that same day.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who is leading an effort to tamp down inflation by aggressively hiking interest rates, has also cited modest wage increases over the past two years as a factor behind rising inflation, expressing his desire to “get wages down” despite evidence that wage growth has slowed in recent months.

Konczal and Lusiani contend in their paper that “while the idea that we are facing the threat of a wage-price spiral is becoming conventional wisdom, this brief and other research finds that changes to labor and worker compensation are not driving factors in recent markups.”

“If margins are unusually high, then there’s the possibility that profits and markups can decrease as either supply opens up or demand cools, removing pricing pressure,” they write. “Such a high profit margin also means that there’s room for wages to increase without necessarily raising prices — an important dynamic in a hot labor market.”

RELATED: Don’t Let Corporations Profit From Our Inflation PainCorporations are blaming rising prices on elected officials and worker organizing even as they rake in record profits.

by Brooke Adams, Truthout

profit over people!!!

BABY FORMULA INDUSTRY SUCCESSFULLY LOBBIED TO WEAKEN BACTERIA SAFETY TESTING STANDARDS

The current formula shortage is traced in part to a contamination-induced shutdown at a key manufacturing plant.

Lee Fang - the intercept

May 13 2022

THE ABBOTT NUTRITION facility in Sturgis, Michigan, which produces much of the U.S. supply of baby formula, shut down in February, bringing production lines to a grinding halt. Following a voluntary recall and investigation by the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the stoppage stemmed from a bacterial outbreak whose effects would be felt months later. Starting last September, five babies who had consumed the plant’s formula contracted bacterial infections. Two of them died.

The production pause is now contributing to a national shortage of formula, a crisis that experts believe will continue for months. Abbott, however, disputes that there is any link between its formula and the infant illnesses.

Questions are now swirling about alleged problems at the Abbott-owned factory, which produces popular brands such as Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare. A recently disclosed whistleblower document claims that managers at the Sturgis plant falsified reports, released untested infant formula, and concealed crucial safety information from federal inspectors.

But eight years earlier, the formula industry rejected an opportunity to take a more proactive approach — not only for increasing supply capacity, but also for preventing a potential outbreak. Records show that the industry successfully mobilized against a 2014 proposal from the FDA to increase regular safety inspections of plants used to manufacture baby formula.

At the time, the FDA had proposed rules to prevent the adulteration of baby formula in any step of the process in order to prevent contamination from salmonella and Cronobacter sakazakii, which led to this year’s Sturgis plant shutdown.

The largest infant formula manufacturers quickly stepped up to delay the safety proposals. The International Formula Council, now known as the Infant Nutrition Council of America, is the lobby group that represents Abbott Nutrition (owned by Abbott Laboratories), Gerber (owned by Nestlé), Perrigo Co., and Reckitt Benckiser Group, the companies that control 89 percent of the baby formula market in the U.S.

In March 2014, the group wrote to FDA officials to request additional time to respond to the proposed rules. The agency, the industry claimed, had used a cost-benefit analysis that “overestimates the expected annual incidence of Cronobacter infection” using “outdated data.” The formula representatives asked for an additional 30 to 45 days.

“We feel the agency and the industry would benefit from this additional time,” wrote Mardi Mountford, an official with the International Formula Council.

That June, after months of deliberation, the FDA released a new interim final proposal that incorporated some of the industry concerns. The rules reduced the frequency of stability testing for new infant formulas from every three months to every four months. The FDA also provided a number of exemptions for manufacturers, allowing them to shirk testing requirements if the “new infant formula will likely not differ from the stability of formulas with similar composition, processing, and packaging for which there are extensive stability data.”

Later that year, the lobby group petitioned the FDA to revisit the safety manufacturing rule with even lower standards, including fewer inspections. In a letter to regulators, Mountford wrote that compliance costs would reach slightly over $20 million a year, including increased personnel and lab fees. “The IFC believes that the additional requirements for end of shelf-life testing under the Final Rule are unnecessary and burdensome and do not provide any additional public health benefit,” Mountford wrote in the September 2014 request. “Based on the frequency of manufacture and store inventories,” the letter noted, “virtually all infant formula is consumed early in its shelf-life (consumers typically purchase and use infant formula between 3 and 9 months after manufacture and do not stockpile infant formula at home).”

The Infant Nutrition Council of America did not respond to a request for comment from The Intercept.

As critics have noted, the formula industry had wide latitude to expand production and increase spending on safety standards. Abbott last year announced that it had spent $5 billion purchasing its own stock.

Abbott Nutrition has declined to inform other outlets whether additional cases of Cronobacter have been identified.

Following publication of this story, a spokesperson for Abbott provided a statement disputing the whistleblower allegations.

“This former employee was dismissed due to serious violations of Abbott’s food safety policies. After dismissal, the former employee, through their attorney, has made evolving, new and escalating allegations to multiple authorities. Abbott is reviewing this new document and will thoroughly investigate any new allegations,” said the Abbott spokesperson.

The spokesperson also provided a statement regarding the Abbott’s trade group lobbying efforts. The International Formula Council’s efforts, said the spokesperson, do “not align with Abbott’s actual past or current practices with regards to testing for Cronobacter sp. Abbott has been conducting finished product testing for Cronobacter sp. in our powdered manufacturing facilities long before the Infant Formula Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) rule requiring this testing was finalized. Additionally, Abbott has always tested for Cronobacter sp. at more than twice the sample size (volume) that FDA requires in 21 CFR Part 106.”

The company on its website claims that there is “is no evidence to link our formulas” to the recent wave of infant illnesses.”

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce is scheduled to hold a hearing on May 25 to investigate.

The Abbott whistleblower allegation was sent to the FDA and Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., in October 2021 and made public last month. DeLauro has demanded that regulators move swiftly in obtaining answers from the company. Despite the whistleblower tip, the FDA did not inspect the Sturgis plant until January 31 of this year, and the recall was not issued until February 17, according to a report from Food Safety News.

Approximately 40 percent of baby formula products were sold out during the week that started on April 24, according to a recent survey. Desperate parents have reportedly turned to eBay, where canisters cost more than six times the retail price. Viral images of empty shelves have alarmed parents, and the Biden administration has said it will take urgent action to address the shortage.

The shortage has other contributing factors. The U.S. maintains strict limits on imports of European brands of infant formula, despite studies showing that products under European Union regulations have high safety and nutrition standards. Competing brands in the U.S. have attempted to ramp up production to make up for the loss of Abbott Nutrition’s Sturgis factory but have encountered supply chain problems.

The production pause is now contributing to a national shortage of formula, a crisis that experts believe will continue for months. Abbott, however, disputes that there is any link between its formula and the infant illnesses.

Questions are now swirling about alleged problems at the Abbott-owned factory, which produces popular brands such as Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare. A recently disclosed whistleblower document claims that managers at the Sturgis plant falsified reports, released untested infant formula, and concealed crucial safety information from federal inspectors.

But eight years earlier, the formula industry rejected an opportunity to take a more proactive approach — not only for increasing supply capacity, but also for preventing a potential outbreak. Records show that the industry successfully mobilized against a 2014 proposal from the FDA to increase regular safety inspections of plants used to manufacture baby formula.

At the time, the FDA had proposed rules to prevent the adulteration of baby formula in any step of the process in order to prevent contamination from salmonella and Cronobacter sakazakii, which led to this year’s Sturgis plant shutdown.

The largest infant formula manufacturers quickly stepped up to delay the safety proposals. The International Formula Council, now known as the Infant Nutrition Council of America, is the lobby group that represents Abbott Nutrition (owned by Abbott Laboratories), Gerber (owned by Nestlé), Perrigo Co., and Reckitt Benckiser Group, the companies that control 89 percent of the baby formula market in the U.S.

In March 2014, the group wrote to FDA officials to request additional time to respond to the proposed rules. The agency, the industry claimed, had used a cost-benefit analysis that “overestimates the expected annual incidence of Cronobacter infection” using “outdated data.” The formula representatives asked for an additional 30 to 45 days.

“We feel the agency and the industry would benefit from this additional time,” wrote Mardi Mountford, an official with the International Formula Council.

That June, after months of deliberation, the FDA released a new interim final proposal that incorporated some of the industry concerns. The rules reduced the frequency of stability testing for new infant formulas from every three months to every four months. The FDA also provided a number of exemptions for manufacturers, allowing them to shirk testing requirements if the “new infant formula will likely not differ from the stability of formulas with similar composition, processing, and packaging for which there are extensive stability data.”

Later that year, the lobby group petitioned the FDA to revisit the safety manufacturing rule with even lower standards, including fewer inspections. In a letter to regulators, Mountford wrote that compliance costs would reach slightly over $20 million a year, including increased personnel and lab fees. “The IFC believes that the additional requirements for end of shelf-life testing under the Final Rule are unnecessary and burdensome and do not provide any additional public health benefit,” Mountford wrote in the September 2014 request. “Based on the frequency of manufacture and store inventories,” the letter noted, “virtually all infant formula is consumed early in its shelf-life (consumers typically purchase and use infant formula between 3 and 9 months after manufacture and do not stockpile infant formula at home).”

The Infant Nutrition Council of America did not respond to a request for comment from The Intercept.

As critics have noted, the formula industry had wide latitude to expand production and increase spending on safety standards. Abbott last year announced that it had spent $5 billion purchasing its own stock.

Abbott Nutrition has declined to inform other outlets whether additional cases of Cronobacter have been identified.

Following publication of this story, a spokesperson for Abbott provided a statement disputing the whistleblower allegations.

“This former employee was dismissed due to serious violations of Abbott’s food safety policies. After dismissal, the former employee, through their attorney, has made evolving, new and escalating allegations to multiple authorities. Abbott is reviewing this new document and will thoroughly investigate any new allegations,” said the Abbott spokesperson.

The spokesperson also provided a statement regarding the Abbott’s trade group lobbying efforts. The International Formula Council’s efforts, said the spokesperson, do “not align with Abbott’s actual past or current practices with regards to testing for Cronobacter sp. Abbott has been conducting finished product testing for Cronobacter sp. in our powdered manufacturing facilities long before the Infant Formula Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) rule requiring this testing was finalized. Additionally, Abbott has always tested for Cronobacter sp. at more than twice the sample size (volume) that FDA requires in 21 CFR Part 106.”

The company on its website claims that there is “is no evidence to link our formulas” to the recent wave of infant illnesses.”

The House Committee on Energy and Commerce is scheduled to hold a hearing on May 25 to investigate.

The Abbott whistleblower allegation was sent to the FDA and Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., in October 2021 and made public last month. DeLauro has demanded that regulators move swiftly in obtaining answers from the company. Despite the whistleblower tip, the FDA did not inspect the Sturgis plant until January 31 of this year, and the recall was not issued until February 17, according to a report from Food Safety News.

Approximately 40 percent of baby formula products were sold out during the week that started on April 24, according to a recent survey. Desperate parents have reportedly turned to eBay, where canisters cost more than six times the retail price. Viral images of empty shelves have alarmed parents, and the Biden administration has said it will take urgent action to address the shortage.

The shortage has other contributing factors. The U.S. maintains strict limits on imports of European brands of infant formula, despite studies showing that products under European Union regulations have high safety and nutrition standards. Competing brands in the U.S. have attempted to ramp up production to make up for the loss of Abbott Nutrition’s Sturgis factory but have encountered supply chain problems.

the best government money can buy!!!

First Quarter of 2022 Sees Record $1 Billion Spent on Lobbying

BY Katherine Huggins, OpenSecrets

PUBLISHED May 8, 2022

This year is on track for record lobbying spending after lobbyists collectively clocked the biggest first quarter haul in history — with more than $1 billion disclosed during the first quarter of 2022 alone.

At this point in 2021, 10,503 lobbyists had brought in less than $929 million across all industries.

The federal budget was the most lobbied issue from January through March, with 3,394 clients paying for lobbying on the issue. Health issues were also heavily lobbied, with 2,068 clients.

Lobbying related to health continues to dominate spending as recovery from the coronavirus pandemic continues.

The health sector accounted for about $187 million in this year’s first quarter and $689 million over the course of 2021. Of the 3,130 lobbyists working for the health sector last year, nearly half — 47.8% — had taken a swing in the revolving door as former government employees.

Within the sector, the pharmaceuticals and health products industry continues to be a top lobbying spender as various companies fight drug pricing regulations, grapple with supply chain issues and seek approval for vaccinations.

Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America ranked third overall in the first quarter of 2022 with nearly $8.3 million in spending during that period. The pharmaceuticals industry trade group was the third largest lobbying spender of 2021 at over $30 million for that full year.

Blue Cross/Blue Shield is the fourth highest lobbying spender overall with about $7.6 million in the first quarter of 2022. The health insurance company spent over $25 million on lobbying last year, making it the fifth biggest lobbying spender overall in 2021.

The American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association are also major lobbying spenders with about $6.6 million in spending from each during the first quarter of 2022. The associations were also neck and neck in 2021 with their national associations spending about $20 million each on lobbying over the year, putting them among the top spenders. Along with its state affiliates, the American Hospital Association’s federal lobbying spending topped $25 million in 2021.

America’s Health Insurance Plans spent another $4.7 million on lobbying in the first quarter of this year, more than any prior quarter in the health insurance industry trade group’s history.

Biotechnology Innovation Organization spent nearly $3.2 million on lobbying in the first quarter of this year, falling lower among the ranks of lobbying spending but remaining a powerful influencer for the biotechnology industry.

Lobbying Stalwarts Continue to Top Spending Charts

While the health industry dominates overall, the top spender of this year’s first quarter was the U.S. Chamber of Commerce with about $19 million in lobbying spending.

A longtime top lobbying spender with more than $1.7 billion spent since 1998, the Chamber spent over $66 million on lobbying in 2021 alone. The business lobbying group’s heavy spending made it the top lobbying spender of 2021 despite fallout among Republicans after the Chamber’s endorsement of 30 Democrats seeking House seats in 2020, which led to several key officials parting ways with the group and criticism from GOP lawmakers.

The Chamber is also a big spender on elections, spending millions on ads targeting politicians it may later lobby. During the 2020 election cycle, the Chamber’s spending on electioneering communications – which can boost and attack candidates without explicitly advocating for their election or defeat – topped $5.7 million.

The National Association of Realtors was the second highest lobbying spender with over $12 million in the first quarter of this year.

The Realtors association was also the second highest spender in 2021 as it faced further scrutiny from the Justice Department related to antitrust issues, pouring about $40 million into lobbying spending over the course of last year. The association’s 2020 lobbying spending topped $84 million, the largest amount the association has spent on lobbying in any single year, and more than any other organization spent on lobbying that year.

While the association’s lobbying spending dipped in 2021, it has a history of dropping in non-election years. The association’s $12 million in first quarter spending is over $4 million more than it spent on lobbying during the same period last year but still about $1.5 million less than it spent during the first quarter in 2020.

Like the Chamber, the National Association of Realtors also spends to influence U.S. elections directly, along with its affiliated political groups, pouring more than $20 million into 2020 spending.

Technology companies were also among the top 10 lobbying spenders of 2022’s first quarter.

Facebook’s parent company, Meta, spent nearly $5.4 million on lobbying while online retail giant Amazon spent over $5.3 million.

At this point in 2021, 10,503 lobbyists had brought in less than $929 million across all industries.

The federal budget was the most lobbied issue from January through March, with 3,394 clients paying for lobbying on the issue. Health issues were also heavily lobbied, with 2,068 clients.

Lobbying related to health continues to dominate spending as recovery from the coronavirus pandemic continues.

The health sector accounted for about $187 million in this year’s first quarter and $689 million over the course of 2021. Of the 3,130 lobbyists working for the health sector last year, nearly half — 47.8% — had taken a swing in the revolving door as former government employees.

Within the sector, the pharmaceuticals and health products industry continues to be a top lobbying spender as various companies fight drug pricing regulations, grapple with supply chain issues and seek approval for vaccinations.

Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America ranked third overall in the first quarter of 2022 with nearly $8.3 million in spending during that period. The pharmaceuticals industry trade group was the third largest lobbying spender of 2021 at over $30 million for that full year.

Blue Cross/Blue Shield is the fourth highest lobbying spender overall with about $7.6 million in the first quarter of 2022. The health insurance company spent over $25 million on lobbying last year, making it the fifth biggest lobbying spender overall in 2021.

The American Hospital Association and the American Medical Association are also major lobbying spenders with about $6.6 million in spending from each during the first quarter of 2022. The associations were also neck and neck in 2021 with their national associations spending about $20 million each on lobbying over the year, putting them among the top spenders. Along with its state affiliates, the American Hospital Association’s federal lobbying spending topped $25 million in 2021.

America’s Health Insurance Plans spent another $4.7 million on lobbying in the first quarter of this year, more than any prior quarter in the health insurance industry trade group’s history.

Biotechnology Innovation Organization spent nearly $3.2 million on lobbying in the first quarter of this year, falling lower among the ranks of lobbying spending but remaining a powerful influencer for the biotechnology industry.

Lobbying Stalwarts Continue to Top Spending Charts

While the health industry dominates overall, the top spender of this year’s first quarter was the U.S. Chamber of Commerce with about $19 million in lobbying spending.

A longtime top lobbying spender with more than $1.7 billion spent since 1998, the Chamber spent over $66 million on lobbying in 2021 alone. The business lobbying group’s heavy spending made it the top lobbying spender of 2021 despite fallout among Republicans after the Chamber’s endorsement of 30 Democrats seeking House seats in 2020, which led to several key officials parting ways with the group and criticism from GOP lawmakers.

The Chamber is also a big spender on elections, spending millions on ads targeting politicians it may later lobby. During the 2020 election cycle, the Chamber’s spending on electioneering communications – which can boost and attack candidates without explicitly advocating for their election or defeat – topped $5.7 million.

The National Association of Realtors was the second highest lobbying spender with over $12 million in the first quarter of this year.

The Realtors association was also the second highest spender in 2021 as it faced further scrutiny from the Justice Department related to antitrust issues, pouring about $40 million into lobbying spending over the course of last year. The association’s 2020 lobbying spending topped $84 million, the largest amount the association has spent on lobbying in any single year, and more than any other organization spent on lobbying that year.

While the association’s lobbying spending dipped in 2021, it has a history of dropping in non-election years. The association’s $12 million in first quarter spending is over $4 million more than it spent on lobbying during the same period last year but still about $1.5 million less than it spent during the first quarter in 2020.

Like the Chamber, the National Association of Realtors also spends to influence U.S. elections directly, along with its affiliated political groups, pouring more than $20 million into 2020 spending.

Technology companies were also among the top 10 lobbying spenders of 2022’s first quarter.

Facebook’s parent company, Meta, spent nearly $5.4 million on lobbying while online retail giant Amazon spent over $5.3 million.

Corporate profiteers blamed price increases on labor costs — then gave big raises to CEOs

Some companies raised prices, blaming rising wages — but actually cut workers' pay, according to new report

By IGOR DERYSH - salon

PUBLISHED APRIL 25, 2022 6:00AM (EDT)

More than a dozen major companies that blamed price increases on rising labor costs gave their top executives big raises — and some of them even slashed workers' pay, according to a new report.

Corporations like Amazon, Apple, McDonald's, Coca-Cola, Verizon and Starbucks cited growing labor costs when they hiked prices on consumers while behind the scenes their CEO-to-worker pay gap grew larger, according to an analysis from the left-leaning watchdog group Accountable.US.

Amazon, which cited "wage increases" while hiking prices on Prime memberships, gave new CEO Andy Jassy about a 600% increase in compensation while founder Jeff Bezos saw his net worth climb over 77% to $201 billion. After the pay hike, the company's CEO pay gap increased by more than 11,000%, meaning that Jassy earns as much as about 6,474 average Amazon employees.

Apple, which cited growing labor costs as one of the reasons it raised prices on new models of the iPhone, increased CEO Tim Cook's pay by 568%, to $98.7 million, and increased its CEO pay gap by 464%, to a ratio of 1,447 to 1. Verizon complained to investors about "labor rates" while looking to hike prices and "pass-through" costs while its CEO pay gap increased by 48%, to 166-to-1, and its median worker pay fell by more than 28% to $48,000.

The 15 companies listed in the report only scratch the surface. The median pay of S&P 500 CEOs rose by 19% to a record of $14.2 million in 2021 while the 4.7% increase in average hourly wages for workers was completely wiped out by rising costs, effectively resulting in a 2.4% decline in wages, according to Labor Department data. CEOs at roughly half the companies in the S&P 500 earned at least 186 times more than the median worker in 2021, according to a recent Wall Street Journal analysis, as median employee pay declined in one-third of the companies.

Despite low unemployment numbers and strong economic growth, working families have been squeezed amid the highest price increases in four decades. At the same time, corporate profits jumped by a record 25% in 2021.

"These higher prices were largely due to corporate profiteering, with S&P 500 companies enjoying near-record operating margins because they had the power to hike prices," the Accountable.US report argued.

"Considering corporate profits are at their highest levels in nearly 50 years, it's safe to say executives have had breathing room in their business decisions," Accountable.US president Kyle Herrig said in a statement to Salon. "Unfortunately, we're seeing a trend of highly profitable companies choosing to enrich a small group of investors and their executives at the expense of their customers and workers."

McDonald's last year blamed price increases in its restaurants in part on "labor inflation" and executives have said they are likely to raise prices again in 2022 despite acknowledging that rising costs "aren't likely to wipe out McDonald's recent gains in profitability," as The Wall Street Journal has reported. The company's net income rose by 59% to $7.55 billion in 2021 and it reported that more than $4.7 billion of that was spent on stock buybacks and shareholder dividends. CEO Chris Kempczinski's compensation last year was more than $20 million, bringing in 2,251 times more than the median employee. The median company salary dropped from $9,124 in 2020 to $8,897 in 2021.

Billionaire investor Carl Icahn, a McDonald's shareholder, called out the company for this "injustice" in a letter to shareholders last Thursday.

"I find the Company's executive compensation, especially relative to the average employee, to be unconscionable," Icahn wrote. "For 2021, total Chief Executive Officer compensation was $20,028,132, an astounding 2,251x the average employee's total compensation of $8,897. The Board is clearly condoning multiple forms of injustice and I believe the majority of the public would agree."

Even as major corporations repeatedly express concerns over inflation and supply chain issues, billionaire CEOs have made out like bandits during the pandemic and economic recovery.

Billionaire Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate saw many of its subsidiaries raise prices to offset a "sharp rise" in labor and material costs, Insider reported last month. At the same time, the company's net earnings increased by 110% to over $90 billion — more than $27 billion of which was spent on stock buybacks. Buffett's net worth increased by 42% to $96 billion in 2021, and another 32% to $127 billion by April 2022, according to Forbes.

Coca-Cola, which was among several big companies that raised costs this year due to "labor problems," reported a 9% increase in revenue that was "driven by a 10% increase in prices," The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this year. The company, which owns a number of beverage brands, saw its net income grow 26% to $9.8 billion last year, $7.3 billion of which it paid in shareholder dividends. CEO James Quincey got a $6.5 million bump in compensation in 2021, earning 1,791 times more than the median company employee.

Starbucks, one of the companies facing a growing nationwide unionization push, raised prices last year and earlier this year while predicting they would rise even more in the future. At the same time, Starbucks' profits increased by 352% after taking a hit during the pandemic and the company committed to $20 billion in stock buybacks and shareholder dividends over the next three years. CEO Kevin Johnson got a 39% pay hike to $20.4 million last year, earning 1,579 times more than the median employee.

HanesBrands executives in February told investors that the company hiked prices in response to "wage pressure" and other cost increases even as they bragged that the company's financial situation was "far stronger" now than before the pandemic. CEO Stephen Bratspies' compensation increased by more than 50% to $11 million, 1,564 times more than the median employee.

Under Armour executives, on a call with investors, said the company faced "rising wages" and other costs but previously reported that it improved its margins "primarily due to pricing benefits." In September, CEO Patrik Frisk said that high demand and supply chain issues presented an "opportunity for us to raise prices." Frisk in February touted record revenue and earnings, and his own compensation increased 111% to more than $15.5 million, or 1,485 times more than the median employee salary.

PepsiCo executives said on an earnings call that it expected "labor cost inflation to persist" but intended to "mitigate the impact of these pressures with its revenue management." The company hiked prices on its products last year and predicted additional price increases in 2022. At the same time, its net income climbed by nearly $500 million to more than $7.6 billion and it spent $5.9 billion of that on stock buybacks and shareholder dividends. The company projected it would spend even more on shareholder handouts in 2022. CEO Ramon Laguarta saw his compensation increase by more than $4 million to $25.5 million, or 488 times more than its median employee earns.

Domino's CEO Ritch Allison last year complained about labor shortages as he teased price hikes for consumers to offset wage increases. But the company's median worker pay actually fell, from $22,076 in 2020 to $17,782 in 2021. At the same time, Allison's compensation increased from $6.3 million to $7.1 million, a pay ratio of 401-to-1.

Kraft Heinz executives cited "labor constraints" and "production constraints" to investors even as it hiked prices and saw bigger profit margins than prior to the pandemic. CEO Miguel Patricio got a 40% pay increase to $8.6 million, making 190 times more than the median employee. The company's net income grew by 183% to more than $1 billion in 2021 and it spent nearly $2 billion on shareholder dividends.

Goodyear, the tire giant, raised prices four times last year, which the company said was in response to growing labor costs and other pressures. CEO Richard Kramer told investors in February that the company "achieved our highest fourth-quarter revenue in nearly 10 years" due to the higher prices. Meanwhile, median worker salary fell from $48,659 to $43,746 while Kramer's compensation increased from $16 million to $21.4 million, 490 times the average employer wage.

The Biden administration has made fighting inflation a top priority amid staggering price increases but has also sought to make clear that corporate profiteering is a major contributor to rising prices. Biden earlier this year called out meatpackers for price gouging, arguing that they had raised prices beyond the increases to their own costs.

"In too many industries, a handful of giant companies dominate the market," Biden said in January, arguing that many big companies are "making our economy less dynamic, giving themselves free rein to raise prices, reduce options for consumers or exploit workers.

Biden last year issued an executive order with 72 initiatives targeting a wide range of industries, including provisions to crack down on "anti-competitive pricing" and enhance consumer protections. He has since pushed the Federal Trade Commission to investigate price gouging by oil companies and prodded the Agriculture Department to investigate poultry and pork companies. The push also includes the Federal Maritime Commission, which Biden pressed to investigate large shipping companies in the supply chain.

Accountable.US backed Biden's efforts to target corporate profiteering in response to rising inflation.

"Can a company that posted huge new profits over the last year while rewarding shareholders and executives by millions honestly say it needed to raise prices so high, or pay their workers so little?" Herrig questioned. "Reining in runaway corporate greed is key to bringing down costs for everyday families."

Corporations like Amazon, Apple, McDonald's, Coca-Cola, Verizon and Starbucks cited growing labor costs when they hiked prices on consumers while behind the scenes their CEO-to-worker pay gap grew larger, according to an analysis from the left-leaning watchdog group Accountable.US.

Amazon, which cited "wage increases" while hiking prices on Prime memberships, gave new CEO Andy Jassy about a 600% increase in compensation while founder Jeff Bezos saw his net worth climb over 77% to $201 billion. After the pay hike, the company's CEO pay gap increased by more than 11,000%, meaning that Jassy earns as much as about 6,474 average Amazon employees.

Apple, which cited growing labor costs as one of the reasons it raised prices on new models of the iPhone, increased CEO Tim Cook's pay by 568%, to $98.7 million, and increased its CEO pay gap by 464%, to a ratio of 1,447 to 1. Verizon complained to investors about "labor rates" while looking to hike prices and "pass-through" costs while its CEO pay gap increased by 48%, to 166-to-1, and its median worker pay fell by more than 28% to $48,000.

The 15 companies listed in the report only scratch the surface. The median pay of S&P 500 CEOs rose by 19% to a record of $14.2 million in 2021 while the 4.7% increase in average hourly wages for workers was completely wiped out by rising costs, effectively resulting in a 2.4% decline in wages, according to Labor Department data. CEOs at roughly half the companies in the S&P 500 earned at least 186 times more than the median worker in 2021, according to a recent Wall Street Journal analysis, as median employee pay declined in one-third of the companies.

Despite low unemployment numbers and strong economic growth, working families have been squeezed amid the highest price increases in four decades. At the same time, corporate profits jumped by a record 25% in 2021.

"These higher prices were largely due to corporate profiteering, with S&P 500 companies enjoying near-record operating margins because they had the power to hike prices," the Accountable.US report argued.

"Considering corporate profits are at their highest levels in nearly 50 years, it's safe to say executives have had breathing room in their business decisions," Accountable.US president Kyle Herrig said in a statement to Salon. "Unfortunately, we're seeing a trend of highly profitable companies choosing to enrich a small group of investors and their executives at the expense of their customers and workers."

McDonald's last year blamed price increases in its restaurants in part on "labor inflation" and executives have said they are likely to raise prices again in 2022 despite acknowledging that rising costs "aren't likely to wipe out McDonald's recent gains in profitability," as The Wall Street Journal has reported. The company's net income rose by 59% to $7.55 billion in 2021 and it reported that more than $4.7 billion of that was spent on stock buybacks and shareholder dividends. CEO Chris Kempczinski's compensation last year was more than $20 million, bringing in 2,251 times more than the median employee. The median company salary dropped from $9,124 in 2020 to $8,897 in 2021.

Billionaire investor Carl Icahn, a McDonald's shareholder, called out the company for this "injustice" in a letter to shareholders last Thursday.

"I find the Company's executive compensation, especially relative to the average employee, to be unconscionable," Icahn wrote. "For 2021, total Chief Executive Officer compensation was $20,028,132, an astounding 2,251x the average employee's total compensation of $8,897. The Board is clearly condoning multiple forms of injustice and I believe the majority of the public would agree."

Even as major corporations repeatedly express concerns over inflation and supply chain issues, billionaire CEOs have made out like bandits during the pandemic and economic recovery.

Billionaire Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway conglomerate saw many of its subsidiaries raise prices to offset a "sharp rise" in labor and material costs, Insider reported last month. At the same time, the company's net earnings increased by 110% to over $90 billion — more than $27 billion of which was spent on stock buybacks. Buffett's net worth increased by 42% to $96 billion in 2021, and another 32% to $127 billion by April 2022, according to Forbes.

Coca-Cola, which was among several big companies that raised costs this year due to "labor problems," reported a 9% increase in revenue that was "driven by a 10% increase in prices," The Wall Street Journal reported earlier this year. The company, which owns a number of beverage brands, saw its net income grow 26% to $9.8 billion last year, $7.3 billion of which it paid in shareholder dividends. CEO James Quincey got a $6.5 million bump in compensation in 2021, earning 1,791 times more than the median company employee.

Starbucks, one of the companies facing a growing nationwide unionization push, raised prices last year and earlier this year while predicting they would rise even more in the future. At the same time, Starbucks' profits increased by 352% after taking a hit during the pandemic and the company committed to $20 billion in stock buybacks and shareholder dividends over the next three years. CEO Kevin Johnson got a 39% pay hike to $20.4 million last year, earning 1,579 times more than the median employee.

HanesBrands executives in February told investors that the company hiked prices in response to "wage pressure" and other cost increases even as they bragged that the company's financial situation was "far stronger" now than before the pandemic. CEO Stephen Bratspies' compensation increased by more than 50% to $11 million, 1,564 times more than the median employee.

Under Armour executives, on a call with investors, said the company faced "rising wages" and other costs but previously reported that it improved its margins "primarily due to pricing benefits." In September, CEO Patrik Frisk said that high demand and supply chain issues presented an "opportunity for us to raise prices." Frisk in February touted record revenue and earnings, and his own compensation increased 111% to more than $15.5 million, or 1,485 times more than the median employee salary.

PepsiCo executives said on an earnings call that it expected "labor cost inflation to persist" but intended to "mitigate the impact of these pressures with its revenue management." The company hiked prices on its products last year and predicted additional price increases in 2022. At the same time, its net income climbed by nearly $500 million to more than $7.6 billion and it spent $5.9 billion of that on stock buybacks and shareholder dividends. The company projected it would spend even more on shareholder handouts in 2022. CEO Ramon Laguarta saw his compensation increase by more than $4 million to $25.5 million, or 488 times more than its median employee earns.

Domino's CEO Ritch Allison last year complained about labor shortages as he teased price hikes for consumers to offset wage increases. But the company's median worker pay actually fell, from $22,076 in 2020 to $17,782 in 2021. At the same time, Allison's compensation increased from $6.3 million to $7.1 million, a pay ratio of 401-to-1.

Kraft Heinz executives cited "labor constraints" and "production constraints" to investors even as it hiked prices and saw bigger profit margins than prior to the pandemic. CEO Miguel Patricio got a 40% pay increase to $8.6 million, making 190 times more than the median employee. The company's net income grew by 183% to more than $1 billion in 2021 and it spent nearly $2 billion on shareholder dividends.

Goodyear, the tire giant, raised prices four times last year, which the company said was in response to growing labor costs and other pressures. CEO Richard Kramer told investors in February that the company "achieved our highest fourth-quarter revenue in nearly 10 years" due to the higher prices. Meanwhile, median worker salary fell from $48,659 to $43,746 while Kramer's compensation increased from $16 million to $21.4 million, 490 times the average employer wage.

The Biden administration has made fighting inflation a top priority amid staggering price increases but has also sought to make clear that corporate profiteering is a major contributor to rising prices. Biden earlier this year called out meatpackers for price gouging, arguing that they had raised prices beyond the increases to their own costs.

"In too many industries, a handful of giant companies dominate the market," Biden said in January, arguing that many big companies are "making our economy less dynamic, giving themselves free rein to raise prices, reduce options for consumers or exploit workers.

Biden last year issued an executive order with 72 initiatives targeting a wide range of industries, including provisions to crack down on "anti-competitive pricing" and enhance consumer protections. He has since pushed the Federal Trade Commission to investigate price gouging by oil companies and prodded the Agriculture Department to investigate poultry and pork companies. The push also includes the Federal Maritime Commission, which Biden pressed to investigate large shipping companies in the supply chain.

Accountable.US backed Biden's efforts to target corporate profiteering in response to rising inflation.

"Can a company that posted huge new profits over the last year while rewarding shareholders and executives by millions honestly say it needed to raise prices so high, or pay their workers so little?" Herrig questioned. "Reining in runaway corporate greed is key to bringing down costs for everyday families."

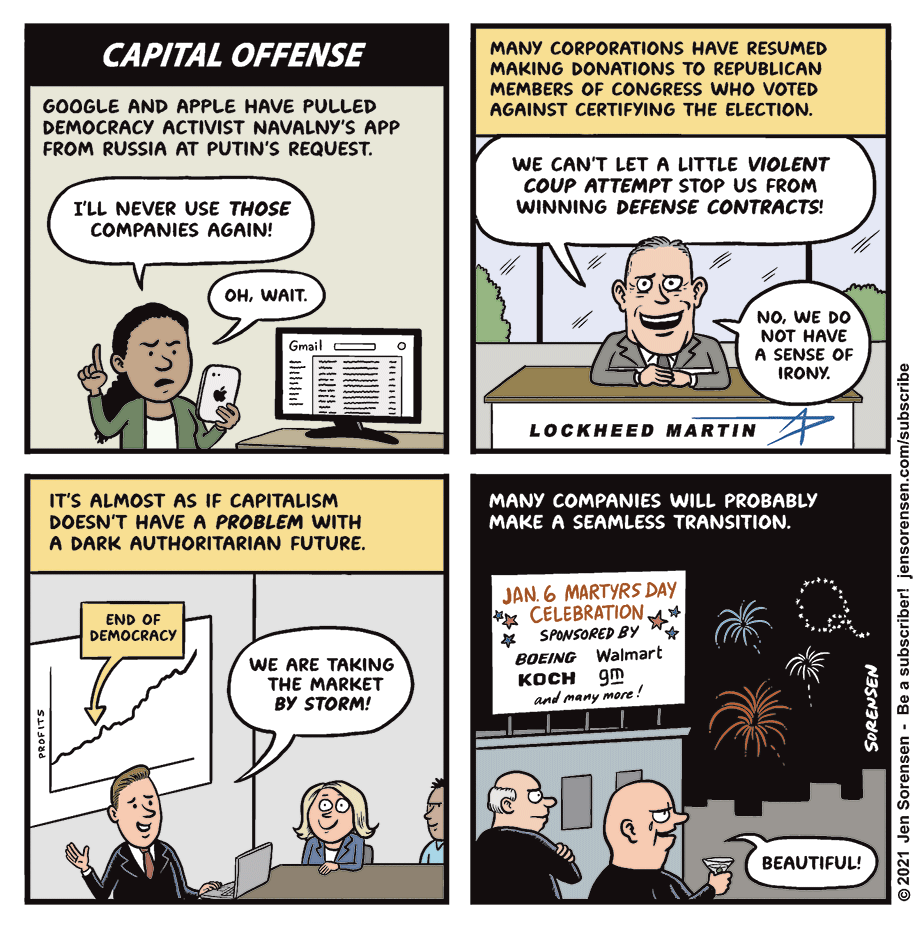

Average US Taxpayer Gave $900 to Military Contractors Last Year

BY Lindsay Koshgarian, OtherWords

PUBLISHED April 17, 2022

Most of us want our tax dollars to be wisely used — especially around tax time.

You’ve probably heard a lot about corporations not paying taxes. Last year, individuals like you contributed six times more in income tax than corporations did.

But have you heard about how many of your tax dollars then end up in corporate pockets? It’s a lot — especially for corporations that contract with the Pentagon. They collect nearly half of all military spending.

The average taxpayer contributed about $2,000 to the military last year, according to a breakdown my colleagues and I prepared for the Institute for Policy Studies. More than $900 of that went to corporate military contractors.

In 2020, the largest Pentagon contractor, Lockheed Martin, took in $75 billion from taxpayers — and paid its CEO more than $23 million.

Unfortunately, this spending isn’t buying us a more secure world.

Last year, Congress added $25 billion the Pentagon didn’t ask for to its already gargantuan budget. Lawmakers even refused to let military leaders retire weapons systems they couldn’t use anymore. The extra money favored top military contractors that gave campaign money to a group of lawmakers, who refused to comment on it.

Then there’s simple price-gouging.

There’s the infamous case of TransDigm, a Pentagon contractor that charged the government $4,361 for a metal pin that should’ve cost $46 — and then refused to share cost data. Congress recently asked TransDigm to repay some of its misbegotten profits, but the Pentagon hasn’t cut off its business.

Somewhere between price-gouging and incompetence lies the F-35 jet fighter, an embarrassment the late Senator John McCain, a Pentagon booster, called “a scandal and a tragedy.”

Among the most expensive weapons systems ever, the F-35 has numerous failings. It’s spontaneously caught fire at least three times — hardly the outcome you’d expect for the top Pentagon contractor’s flagship program. The Pentagon has reduced its request for new F-35s this year by about a third, but Congress may reject that too.

Most serious of all, there’s the problem of U.S. weapons feeding conflicts in ways the Pentagon didn’t foresee, but probably should have.

When U.S. ground troops left Afghanistan, they left behind a huge array of military equipment, from armored vehicles to aircraft, that could now be in Taliban hands. The U.S. also left weapons in Iraq that fell into the hands of ISIS, including guns and an anti-tank missile.

Even weapons we sold to so-called allies like Saudi Arabia have ended up going to people affiliated with groups like al Qaeda.

Military weapons also end up on city streets at home. Over the years, civilian law agencies have received guns, armored vehicles, and even grenade launchers from the military, turning local police into near-military organizations.

Records also show that the Pentagon has lost hundreds of weapons which may have been stolen, including grenade launchers and rocket launchers. Some of these weapons have been used in crimes.

Taxpayers shouldn’t be spending $900 apiece for these outcomes. My team at the Institute for Policy Studies and others have demonstrated ways to cut up to $350 billion per year from the Pentagon budget, including what we spend on weapons contractors, without compromising our safety.

Even better, we could then put some of that money elsewhere.

Compared to the $900 for Pentagon contractors, the average taxpayer contributed only about $27 to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, $171 to K-12 education, and barely $5 to renewable energy.

How much more could we get if we invested even a fraction of what we spend on military contractors for these dire needs?

Most Americans support shifting Pentagon funds to pay for domestic needs. Instead of making Americans fork over another $900 to corporate military contractors this year, Congress should put our dollars to better use.

You’ve probably heard a lot about corporations not paying taxes. Last year, individuals like you contributed six times more in income tax than corporations did.

But have you heard about how many of your tax dollars then end up in corporate pockets? It’s a lot — especially for corporations that contract with the Pentagon. They collect nearly half of all military spending.

The average taxpayer contributed about $2,000 to the military last year, according to a breakdown my colleagues and I prepared for the Institute for Policy Studies. More than $900 of that went to corporate military contractors.

In 2020, the largest Pentagon contractor, Lockheed Martin, took in $75 billion from taxpayers — and paid its CEO more than $23 million.

Unfortunately, this spending isn’t buying us a more secure world.

Last year, Congress added $25 billion the Pentagon didn’t ask for to its already gargantuan budget. Lawmakers even refused to let military leaders retire weapons systems they couldn’t use anymore. The extra money favored top military contractors that gave campaign money to a group of lawmakers, who refused to comment on it.

Then there’s simple price-gouging.

There’s the infamous case of TransDigm, a Pentagon contractor that charged the government $4,361 for a metal pin that should’ve cost $46 — and then refused to share cost data. Congress recently asked TransDigm to repay some of its misbegotten profits, but the Pentagon hasn’t cut off its business.

Somewhere between price-gouging and incompetence lies the F-35 jet fighter, an embarrassment the late Senator John McCain, a Pentagon booster, called “a scandal and a tragedy.”