the real world

exposing how greed, corruption, injustice, and imperialism impacts the world

and exposes the leaders who benefit

october 2022

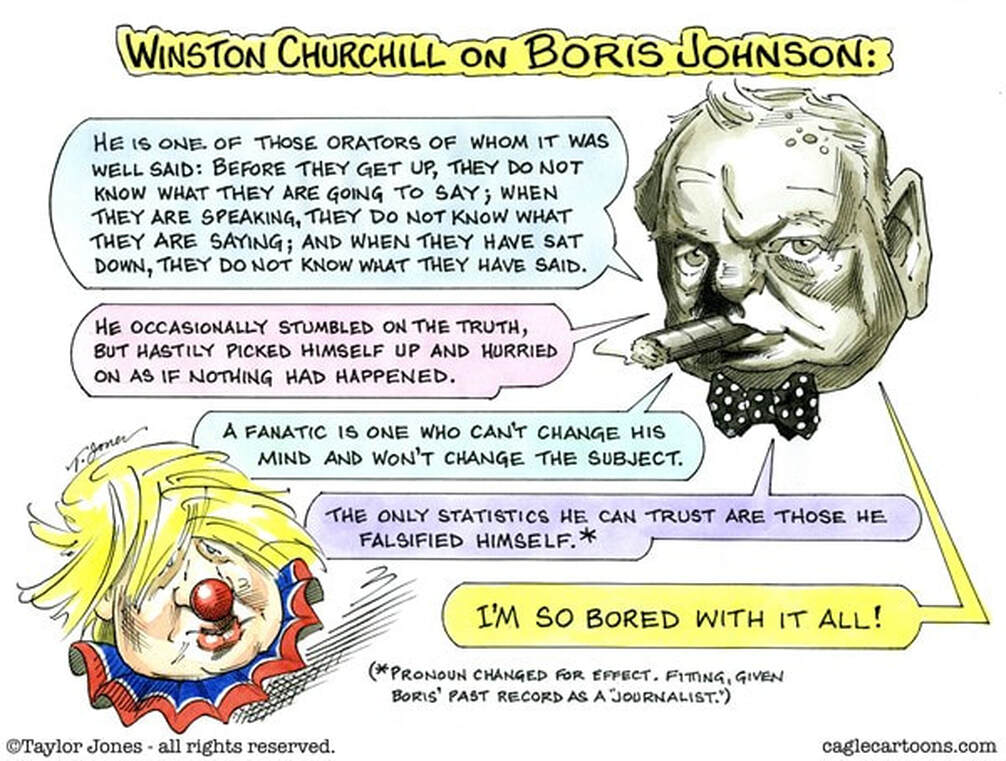

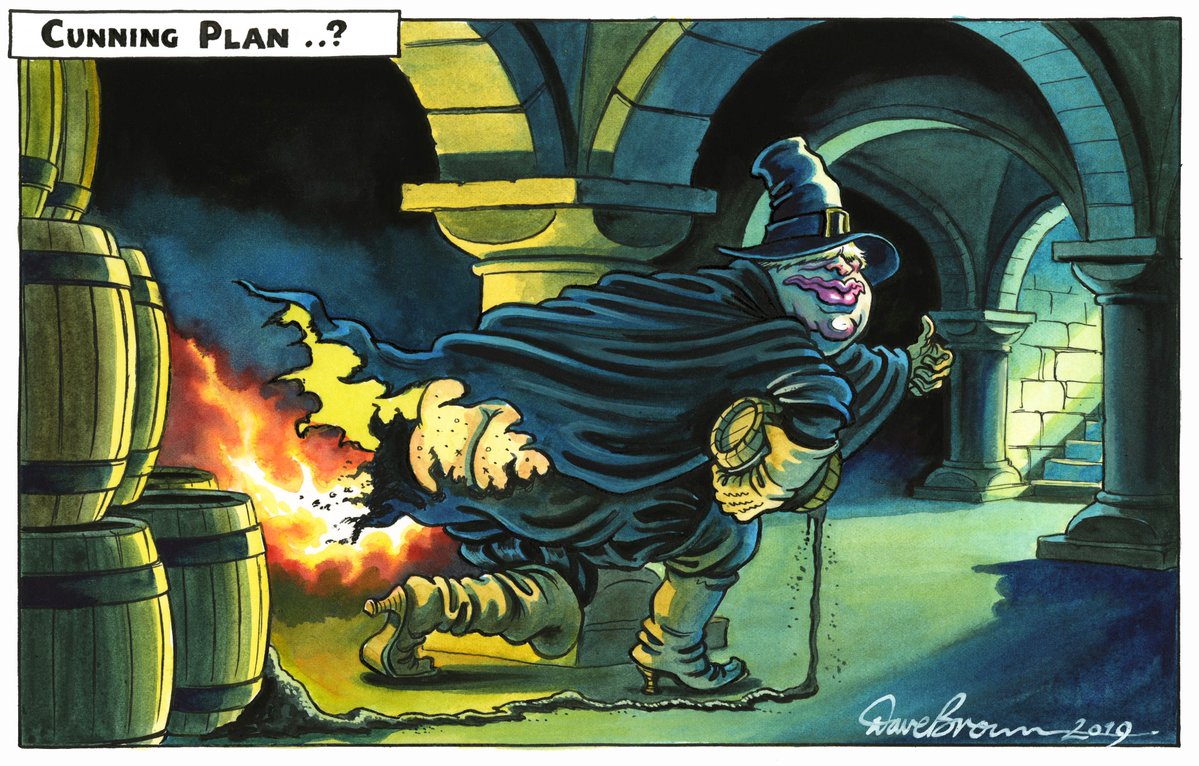

*Boris Johnson referred to police watchdog over alleged relationship with American businesswoman The prime minister of Great Britain may be facing an investigation as impeachment grips America.

Man becomes great exactly in the degree in which he works for the welfare of his fellow-men

Mahatma Gandhi

articles

*ISRAEL KILLED UP TO 192 PALESTINIAN CIVILIANS IN MAY 2021 ATTACKS ON GAZA

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Israel and the Racial Politics of Palestinian Family Separation

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*BUCKINGHAM PALACE BANNED ETHNIC MINORITIES FROM OFFICE ROLES, PAPERS REVEAL

(ARTICLE BELOW)

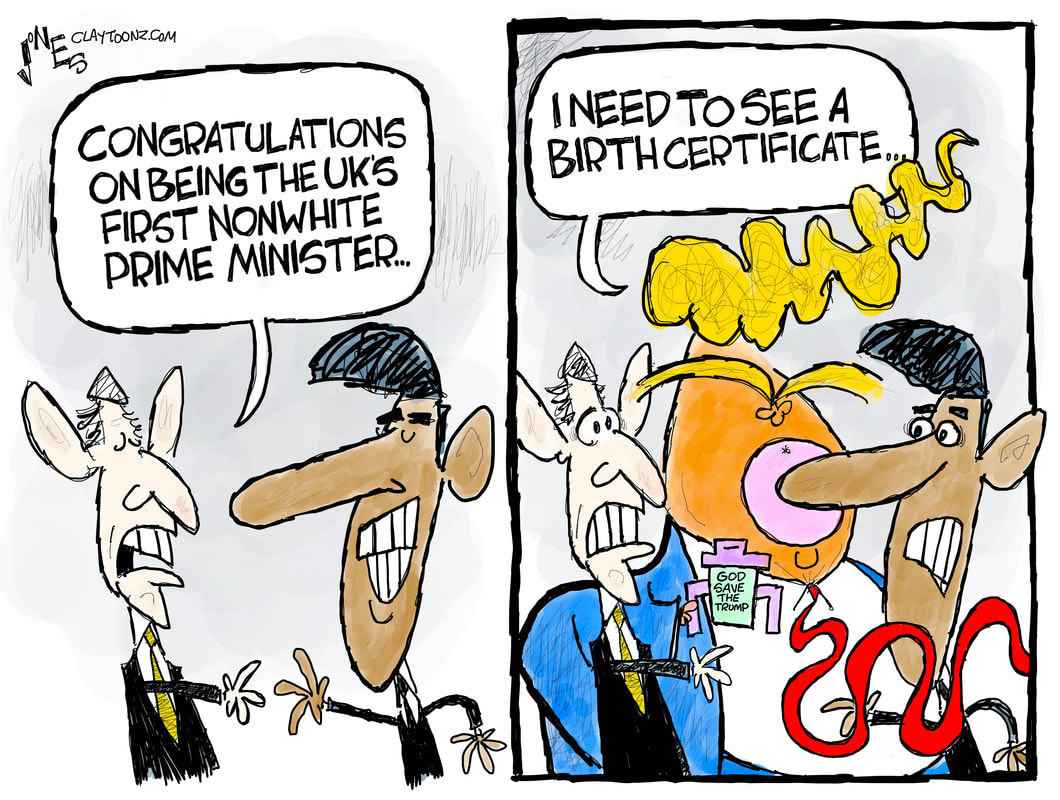

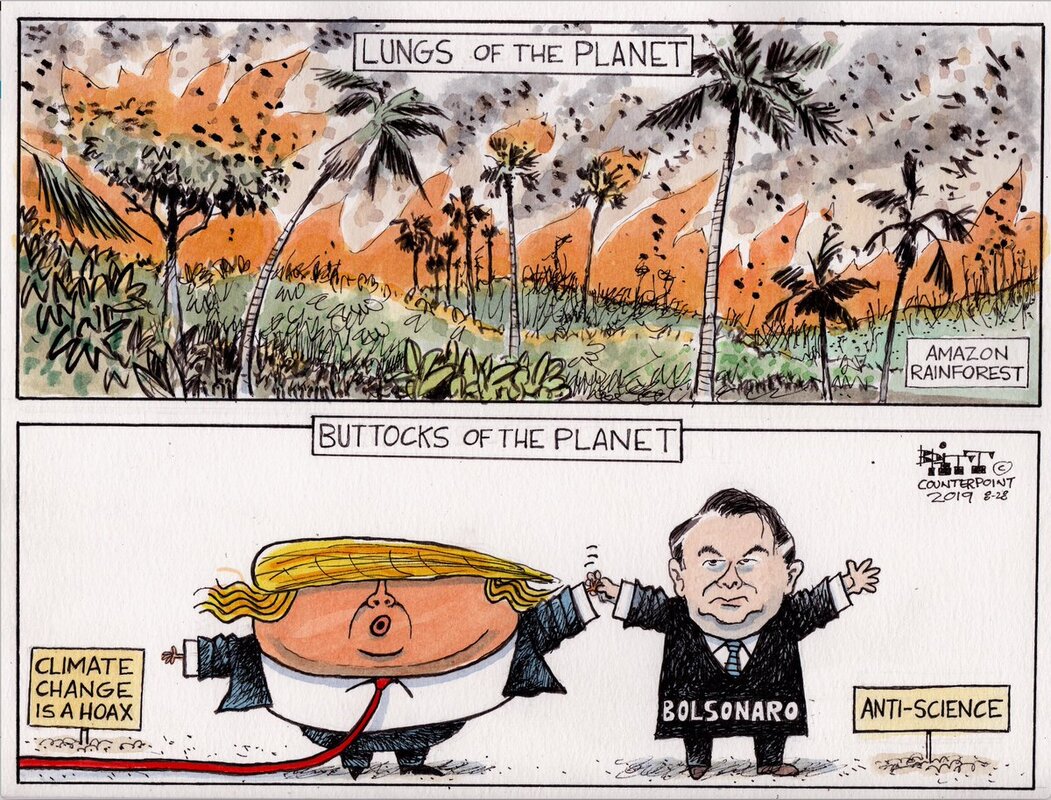

*Gender equality: Most people are biased against women, UN says

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The super-rich: another 31,000 people join the ultra-wealthy elite

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*DELHI PROTESTS: DEATH TOLL CLIMBS AMID WORST RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE FOR DECADES

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*UK to close door to non-English speakers and unskilled workers

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*No 10 refuses to comment on PM's views of racial IQ

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Germany Sees Political Fallout From Chancellor Merkel’s Alliance With Far Right

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Vietnam accused of teaching young people that being gay is a ‘disease’

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Canada: thousands of travelers affected as Indigenous-led rail blockade continues

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Illegal Chinese Chef Charged for Caning Black Employee In Kenya

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Abbas blasts Trump’s ‘Swiss cheese’ plan for Palestine in UN speech

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Botswana Selling Licenses To Kill Elephants At $39,000 A Head

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Women Perform 12.5 Billion Hours of Unpaid Labor Every Day

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Here’s What Workers of the Global South Endure to Create Corporate Wealth

(ARTICLE BELOW)

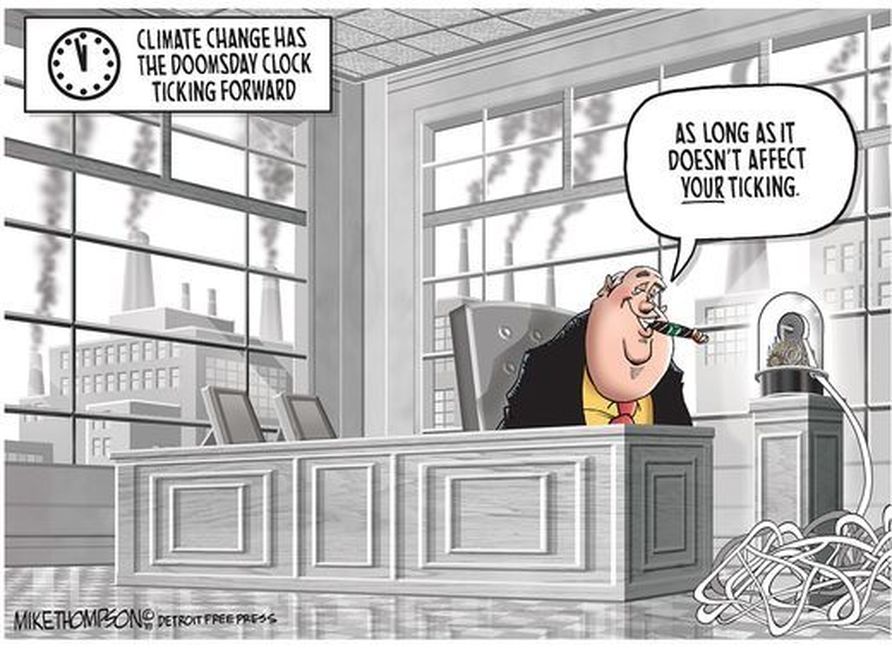

funnies(at the end)

*World Highlights*

ISRAEL KILLED UP TO 192 PALESTINIAN CIVILIANS IN MAY 2021 ATTACKS ON GAZA

More than 70 percent of the Israeli attacks that killed civilians in Gaza had no corresponding reports of militants hit alongside them.

Murtaza Hussain - the intercept

December 9 2021,

A NEW REPORT by the independent monitoring group Airwars found that the 2021 conflict between Israel and Palestinian factions in the Gaza Strip killed up to 192 Palestinian civilians and injured hundreds more over 11 days of intense fighting. Rockets fired by Palestinian militants into Israel are also estimated to have killed 10 civilians inside Israel during the brief but intense conflict first triggered by tensions between Israelis and Palestinians in Jerusalem.

Among the key findings of the report — titled “Why Did They Bomb Us?” — are the age breakdowns of Palestinians killed in Israeli strikes in Gaza. Of the total number of civilian deaths, roughly one-third were children, most of whom died in attacks that killed or wounded multiple members of the same family. More than 70 percent of the reported attacks that killed civilians had no corresponding reports of militants hit alongside them, meaning that civilians were the only victims.

One attack documented in the report took place the night of May 15, when an Israeli airstrike hit a house in the Al-Shati refugee camp in Gaza. Two mothers, sisters-in-law, were reportedly killed in the attack, along with eight children between the ages of 5 and 14. One 5-month-old boy was found by rescuers in the rubble from the attack still alive in his dead mother’s arms. The families had gathered together to celebrate the long weekend after the Eid holiday.

Alaa Abu Hattab, whose wife, children, sister, and sister’s children were all killed in the attack, recounted to Airwars what took place.

“I left my house on foot at about 1:30AM to go to some of the local shops that were open late during the run-up to Eid to buy toys and snacks for the kids for the Eid festival and to buy some food, as we were hungry,” Abu Hattab said in the report. Fifteen minutes later, an explosion hit the area he had just left. He ran back to find that it was his own home that had been struck. Seeing the rubble where his family house once stood, he fainted in shock. “When I regained consciousness, I saw rescue workers looking for bodies under the rubble and recovering body parts. The attack had shredded the bodies. Other parts remained under the rubble because they could not find them.”

No militants were reported killed in the strike, one of many that hit the strip during the brief fighting. “There were no militants in or near my house and no rockets or rocket launchers there,” Abu Hattab told Airwars. “I still don’t know why they bombed my house and killed my wife and children and my sister and her children.”

In addition to providing details on the civilian impact of the last war in Gaza, the Airwars report also provides the first comprehensive review of the long-running Israeli air campaign in Syria. Civilian casualties in Israel’s air campaign in Syria, mostly targeting alleged Iranian and Hezbollah assets, have been light, particularly in comparison with U.S., Russian, and Syrian government aerial attacks there that have killed tens of thousands of people. An estimated 14 to 40 civilians have been killed across hundreds of Israeli strikes against air bases, troop convoys, and weapons stores since 2013, according to Airwars findings.

The relative precision of Israel’s attacks in Syria stands in stark contrast to the toll of its operations in Gaza. According to the report, more civilians were killed in Gaza during the fighting this summer than in all of the attacks that have been carried out in Syria over the past eight years. The staggering difference between civilian harm in the two campaigns raises “fundamental questions about targeting policies,” according to the report. Israeli strikes in Syria have largely taken place away from built-up civilian areas, whereas the Gaza Strip is one of the most densely populated regions on the planet — making the nature of the Israeli campaign there something closer to counterinsurgency carried out from the skies.

In response to questions about its targeting practices during the 11-day Gaza conflict, an Israel Defense Forces spokesperson told Airwars that “terror organizations in the Gaza Strip deliberately embed their military assets in densely populated civilian areas,” adding that the IDF conducted internal operational reviews of its strikes and that the findings from those reports were classified. In response to similar questions about its attacks on Israel, a Hamas spokesperson stated that “[Israeli] military compounds and security facilities are built inside big cities and near universities and near hospitals,” claiming that the group similarly issued warnings in the hours before it carried out its attacks and took steps to ensure that its operations complied with international law.

The Airwars report is only the latest in a series from the monitoring organization on the civilian toll of various air campaigns in the Middle East and North Africa, including the U.S.-led coalition war against the Islamic State, Russian and Turkish airstrikes in Syria, and international operations in Libya. The study on Israeli and Palestinian militant activity is the first of its kind from the group.

“Our latest study corroborates what we have found with other large-scale conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere: Even technologically advanced militaries kill large numbers of civilians when attacks focus on urban centers,” Airwars Director Chris Woods said about the report. “Stark differences in civilian deaths and injuries from Israeli actions in Syria and in the Gaza Strip clearly illustrate that the most significant driver of civilian harm remains the use of explosive weapons in populated areas. The single most effective way to reduce the number of civilians dying in warfare would be to restrict the use of such dangerous wide-area effect weapons.”

Among the key findings of the report — titled “Why Did They Bomb Us?” — are the age breakdowns of Palestinians killed in Israeli strikes in Gaza. Of the total number of civilian deaths, roughly one-third were children, most of whom died in attacks that killed or wounded multiple members of the same family. More than 70 percent of the reported attacks that killed civilians had no corresponding reports of militants hit alongside them, meaning that civilians were the only victims.

One attack documented in the report took place the night of May 15, when an Israeli airstrike hit a house in the Al-Shati refugee camp in Gaza. Two mothers, sisters-in-law, were reportedly killed in the attack, along with eight children between the ages of 5 and 14. One 5-month-old boy was found by rescuers in the rubble from the attack still alive in his dead mother’s arms. The families had gathered together to celebrate the long weekend after the Eid holiday.

Alaa Abu Hattab, whose wife, children, sister, and sister’s children were all killed in the attack, recounted to Airwars what took place.

“I left my house on foot at about 1:30AM to go to some of the local shops that were open late during the run-up to Eid to buy toys and snacks for the kids for the Eid festival and to buy some food, as we were hungry,” Abu Hattab said in the report. Fifteen minutes later, an explosion hit the area he had just left. He ran back to find that it was his own home that had been struck. Seeing the rubble where his family house once stood, he fainted in shock. “When I regained consciousness, I saw rescue workers looking for bodies under the rubble and recovering body parts. The attack had shredded the bodies. Other parts remained under the rubble because they could not find them.”

No militants were reported killed in the strike, one of many that hit the strip during the brief fighting. “There were no militants in or near my house and no rockets or rocket launchers there,” Abu Hattab told Airwars. “I still don’t know why they bombed my house and killed my wife and children and my sister and her children.”

In addition to providing details on the civilian impact of the last war in Gaza, the Airwars report also provides the first comprehensive review of the long-running Israeli air campaign in Syria. Civilian casualties in Israel’s air campaign in Syria, mostly targeting alleged Iranian and Hezbollah assets, have been light, particularly in comparison with U.S., Russian, and Syrian government aerial attacks there that have killed tens of thousands of people. An estimated 14 to 40 civilians have been killed across hundreds of Israeli strikes against air bases, troop convoys, and weapons stores since 2013, according to Airwars findings.

The relative precision of Israel’s attacks in Syria stands in stark contrast to the toll of its operations in Gaza. According to the report, more civilians were killed in Gaza during the fighting this summer than in all of the attacks that have been carried out in Syria over the past eight years. The staggering difference between civilian harm in the two campaigns raises “fundamental questions about targeting policies,” according to the report. Israeli strikes in Syria have largely taken place away from built-up civilian areas, whereas the Gaza Strip is one of the most densely populated regions on the planet — making the nature of the Israeli campaign there something closer to counterinsurgency carried out from the skies.

In response to questions about its targeting practices during the 11-day Gaza conflict, an Israel Defense Forces spokesperson told Airwars that “terror organizations in the Gaza Strip deliberately embed their military assets in densely populated civilian areas,” adding that the IDF conducted internal operational reviews of its strikes and that the findings from those reports were classified. In response to similar questions about its attacks on Israel, a Hamas spokesperson stated that “[Israeli] military compounds and security facilities are built inside big cities and near universities and near hospitals,” claiming that the group similarly issued warnings in the hours before it carried out its attacks and took steps to ensure that its operations complied with international law.

The Airwars report is only the latest in a series from the monitoring organization on the civilian toll of various air campaigns in the Middle East and North Africa, including the U.S.-led coalition war against the Islamic State, Russian and Turkish airstrikes in Syria, and international operations in Libya. The study on Israeli and Palestinian militant activity is the first of its kind from the group.

“Our latest study corroborates what we have found with other large-scale conflicts in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere: Even technologically advanced militaries kill large numbers of civilians when attacks focus on urban centers,” Airwars Director Chris Woods said about the report. “Stark differences in civilian deaths and injuries from Israeli actions in Syria and in the Gaza Strip clearly illustrate that the most significant driver of civilian harm remains the use of explosive weapons in populated areas. The single most effective way to reduce the number of civilians dying in warfare would be to restrict the use of such dangerous wide-area effect weapons.”

Israel and the Racial Politics of Palestinian Family Separation

JUAN COLE - informed comment

07/07/2021

Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – The Israeli newspaper Arab 48 reports that on Tuesday, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett slammed opposition parties, led by former PM Binyamin Netanyahu, for having voted against renewal of the Family Separation Law for Palestinian-Israelis married to Palestinians. He said that the opposition had done direct damage to Israeli security. The quotes below are from the Arab 48 article.

Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked complained that now her office would receive 15,000 requests for family unification and for citizenship for Palestinian spouses of Israelis.

Israeli citizens of Jewish heritage may marry anyone they wish abroad and may bring their spouse back to Israel without let or hindrance. A 2003 law, however, places obstacles in the way of Israelis of Palestinian heritage who marry stateless Palestinians in the Occupied West Bank or Gaza and wish to bring their spouses home. Gaza spouses are excluded from Israel. West Bank spouses can sometimes get a temporary, renewable permit to come live with their family in Israel proper or in the illegally annexed East Jerusalem area. It is estimated that some 17,000 Palestinian-Israeli families are affected by the Family Separation Act. I call Israelis of Palestinian extraction Palestinian-Israelis on the model of Italian-Americans. In Israel, they are called Arab Israelis, a term that erases their Palestinian national identity; it would be like calling Italian-Americans “European Americans.” They make up over 20 percent of the Israeli population.

The Bennett government tried to renew the 2003 law on Monday, but failed because the opposition parties voted against the measure or abstained, and because a couple of members of parliament in Bennett’s unwieldy eight-party coalition also voted against. Bennett’s coalition has 61 seats in the 120-seat Knesset or parliament, a razor-thin majority. If 61 members of parliament had voted a straight “no” on the renewal, Bennett’s government would have fallen and Israel would have gone to new elections. The abstentions saved Bennett’s prime ministership, since there were only 59 “no” votes.

Netanyahu, in forbidding the far right opposition parties to vote for renewal, was attempting to induce a vote of no confidence, opening the way for him to return to the office of prime minister, and he narrowly failed. He also wanted to demonstrate that the Bennett government cannot hope to govern and legislate effectively. The side effect of this maneuver, however, was to allow the Family Separation Act for Palestinian-Israelis married to Palestinians to lapse.

The law is inherently racist and was cited by Human Rights Watch as evidence that Israel engages in Apartheid practices. The Israeli establishment, however, does not see its Jim Crow implications, and so the recriminations on Tuesday consisted of some Israeli Jews accusing other Israeli Jews of having endangered the Jewish majority in Israel by letting the law lapse.

Actually, people mostly marry others in their town, and of some 1.6 million Palestinian-Israelis, only 17,000 have married West Bank or Gaza Palestinians. That isn’t a danger to the Jewish majority in Israel. But anyway, worrying about having a Jewish majority in Israel is like worrying about having a white majority in the United States. It is a racist concern.

In fact, it is as though the United States had a law that African-Americans who marry people of color abroad may not bring them back as spouses to live in the U.S. lest they dilute the white majority and endanger American security. These are literally the analogous terms of debate in Israel, which creeps me out. It is like listening to Strom Thurmond debating George Wallace on just how much of a danger Negroes are to the country.[...]

Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked complained that now her office would receive 15,000 requests for family unification and for citizenship for Palestinian spouses of Israelis.

Israeli citizens of Jewish heritage may marry anyone they wish abroad and may bring their spouse back to Israel without let or hindrance. A 2003 law, however, places obstacles in the way of Israelis of Palestinian heritage who marry stateless Palestinians in the Occupied West Bank or Gaza and wish to bring their spouses home. Gaza spouses are excluded from Israel. West Bank spouses can sometimes get a temporary, renewable permit to come live with their family in Israel proper or in the illegally annexed East Jerusalem area. It is estimated that some 17,000 Palestinian-Israeli families are affected by the Family Separation Act. I call Israelis of Palestinian extraction Palestinian-Israelis on the model of Italian-Americans. In Israel, they are called Arab Israelis, a term that erases their Palestinian national identity; it would be like calling Italian-Americans “European Americans.” They make up over 20 percent of the Israeli population.

The Bennett government tried to renew the 2003 law on Monday, but failed because the opposition parties voted against the measure or abstained, and because a couple of members of parliament in Bennett’s unwieldy eight-party coalition also voted against. Bennett’s coalition has 61 seats in the 120-seat Knesset or parliament, a razor-thin majority. If 61 members of parliament had voted a straight “no” on the renewal, Bennett’s government would have fallen and Israel would have gone to new elections. The abstentions saved Bennett’s prime ministership, since there were only 59 “no” votes.

Netanyahu, in forbidding the far right opposition parties to vote for renewal, was attempting to induce a vote of no confidence, opening the way for him to return to the office of prime minister, and he narrowly failed. He also wanted to demonstrate that the Bennett government cannot hope to govern and legislate effectively. The side effect of this maneuver, however, was to allow the Family Separation Act for Palestinian-Israelis married to Palestinians to lapse.

The law is inherently racist and was cited by Human Rights Watch as evidence that Israel engages in Apartheid practices. The Israeli establishment, however, does not see its Jim Crow implications, and so the recriminations on Tuesday consisted of some Israeli Jews accusing other Israeli Jews of having endangered the Jewish majority in Israel by letting the law lapse.

Actually, people mostly marry others in their town, and of some 1.6 million Palestinian-Israelis, only 17,000 have married West Bank or Gaza Palestinians. That isn’t a danger to the Jewish majority in Israel. But anyway, worrying about having a Jewish majority in Israel is like worrying about having a white majority in the United States. It is a racist concern.

In fact, it is as though the United States had a law that African-Americans who marry people of color abroad may not bring them back as spouses to live in the U.S. lest they dilute the white majority and endanger American security. These are literally the analogous terms of debate in Israel, which creeps me out. It is like listening to Strom Thurmond debating George Wallace on just how much of a danger Negroes are to the country.[...]

the queen of discrimination!!!

Buckingham Palace banned ethnic minorities from office roles, papers reveal

Exclusive: Documents also shed light on Queen’s ongoing exemption from race and sex discrimination laws

by David Pegg and Rob Evans - the guardian

6/2/2021

The Queen’s courtiers banned “coloured immigrants or foreigners” from serving in clerical roles in the royal household until at least the late 1960s, according to newly discovered documents that will reignite the debate over the British royal family and race.

The documents also shed light on how Buckingham Palace negotiated controversial clauses – that remain in place to this day – exempting the Queen and her household from laws that prevent race and sex discrimination.

The papers were discovered at the National Archives as part of the Guardian’s ongoing investigation into the royal family’s use of an arcane parliamentary procedure, known as Queen’s consent, to secretly influence the content of British laws.

They reveal how in 1968, the Queen’s chief financial manager informed civil servants that “it was not, in fact, the practice to appoint coloured immigrants or foreigners” to clerical roles in the royal household, although they were permitted to work as domestic servants.

It is unclear when the practice ended. Buckingham Palace refused to answer questions about the ban and when it was revoked. It said its records showed people from ethnic minority backgrounds being employed in the 1990s. It added that before that decade, it did not keep records on the racial backgrounds of employees.

Exemptions from the law

In the 1960s government ministers sought to introduce laws that would make it illegal to refuse to employ an individual on the grounds of their race or ethnicity.

The Queen has remained personally exempted from those equality laws for more than four decades. The exemption has made it impossible for women or people from ethnic minorities working for her household to complain to the courts if they believe they have been discriminated against.

In a statement, Buckingham Palace did not dispute that the Queen had been exempted from the laws, adding that it had a separate process for hearing complaints related to discrimination. The palace did not respond when asked what this process consists of.

The exemption from the law was brought into force in the 1970s, when politicians implemented a series of racial and sexual equality laws to eradicate discrimination.

The official documents reveal how government officials in the 1970s coordinated with Elizabeth Windsor’s advisers on the wording of the laws.

The documents are likely to refocus attention on the royal family’s historical and current relationship with race.

Much of the family’s history is inextricably linked with the British empire, which subjugated people around the world. Some members of the royal family have also been criticised for their racist comments.

In March the Duchess of Sussex, the family’s first mixed-race member, said she had had suicidal thoughts during her time in the royal family, and alleged that a member of the family had expressed concern about her child’s skin colour.

The allegation compelled her brother-in-law, Prince William, to declare that the royal family was “very much not” racist.

Queen’s consent

Some of the documents uncovered by the Guardian relate to the use of Queen’s consent, an obscure parliamentary mechanism through which the monarch grants parliament permission to debate laws that affect her and her private interests.

Buckingham Palace says the process is a mere formality, despite compelling evidence that the Queen has repeatedly used the power to secretly lobby ministers to amend legislation she does not like.

The newly discovered documents reveal how the Queen’s consent procedure was used to secretly influence the formation of the draft race relations legislation.

In 1968, the then home secretary, James Callaghan, and civil servants at the Home Office appear to have believed that they should not request Queen’s consent for parliament to debate the race relations bill until her advisers were satisfied it could not be enforced against her in the courts.

At the time, Callaghan wanted to expand the UK’s racial discrimination laws, which only prohibited discrimination in public places, so that they also prevented racism in employment or services such as housing.

A key proposal of the bill was the Race Relations Board, which would act as an ombudsman for discrimination complaints and could bring court proceedings against individuals or companies that maintained racist practices.

‘Not the practice to appoint coloured immigrants’

In February 1968, a Home Office civil servant, TG Weiler, summarised the progress of discussions with Lord Tryon, the keeper of the privy purse, who was responsible for managing the Queen’s finances, and other courtiers.

Tryon, he wrote, had informed them Buckingham Palace was prepared to comply with the proposed law, but only if it enjoyed similar exemptions to those provided to the diplomatic service, which could reject job applicants who had been resident in the UK for less than five years.

According to Weiler, Tryon considered staff in the Queen’s household to fall into one of three types of roles: “(a) senior posts, which were not filled by advertising or by any overt system of appointment and which would presumably be accepted as outside the scope of the bill; (b) clerical and other office posts, to which it was not, in fact, the practice to appoint coloured immigrants or foreigners; and (c) ordinary domestic posts for which coloured applicants were freely considered, but which would in any event be covered by the proposed general exemption for domestic employment.”

“They were particularly concerned,” Weiler wrote, “that if the proposed legislation applied to the Queen’s household it would for the first time make it legally possible to criticise the household. Many people do so already, but this has to be accepted and is on a different footing from a statutory provision.”

By March, Buckingham Palace was satisfied with the proposed law. A Home Office official noted that the courtiers “agreed that the way was now open for the secretary of state to seek the Queen’s consent to place her interest at the disposal of parliament for the purpose of the bill.”

The phrasing of the documents is highly significant, because it suggests that Callaghan and the Home Office officials believed it might not be possible to obtain the Queen’s consent for parliament to debate the racial equality law unless the monarch was assured of her exemption.

As a result of this exemption, the Race Relations Board that was given the task of investigating racial discrimination would send any complaints from the Queen’s staff to the home secretary rather than the courts.

In the 1970s, the government brought in three laws to counter racial and sexual discrimination in the workplace. Complainants in general were empowered to take their cases directly to the courts.

But staff in the royal household were specifically prevented from doing so, although the wording of the ban was sufficiently vague that the public might not have realised the monarch’s staff had been exempted.

A civil servant noted that the exemption in the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act had been “acceptable to the palace, largely because it did not explicitly single out persons employed by Her Majesty in her personal capacity for special exception” while still removing them from its scope.

The exemption was extended to the present day when in 2010 the Equality Act replaced the 1976 Race Relations Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1970 Equal Pay Act. For many years, critics have regularly pointed out that the royal household employed few black, Asian or minority-ethnic people.

In 1990 the journalist Andrew Morton reported in the Sunday Times that “a black face has never graced the executive echelons of royal service – the household and officials” and “even among clerical and domestic staff, there is only a handful of recruits from ethnic minorities”.

The following year, the royal researcher Philip Hall published a book, Royal Fortune, in which he cited a source close to the Queen confirming that there were no non-white courtiers in the palace’s most senior ranks.

In 1997 the Palace admitted to the Independent that it was not carrying out an officially recommended policy of monitoring staff numbers to ensure equal opportunities.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson said: “The royal household and the sovereign comply with the provisions of the Equality Act, in principle and in practice. This is reflected in the diversity, inclusion and dignity at work policies, procedures and practices within the royal household.

“Any complaints that might be raised under the act follow a formal process that provides a means of hearing and remedying any complaint.” The palace did not respond when asked if the monarch was subject to this act in law.

By March, Buckingham Palace was satisfied with the proposed law. A Home Office official noted that the courtiers “agreed that the way was now open for the secretary of state to seek the Queen’s consent to place her interest at the disposal of parliament for the purpose of the bill.”

The phrasing of the documents is highly significant, because it suggests that Callaghan and the Home Office officials believed it might not be possible to obtain the Queen’s consent for parliament to debate the racial equality law unless the monarch was assured of her exemption.

As a result of this exemption, the Race Relations Board that was given the task of investigating racial discrimination would send any complaints from the Queen’s staff to the home secretary rather than the courts.

In the 1970s, the government brought in three laws to counter racial and sexual discrimination in the workplace. Complainants in general were empowered to take their cases directly to the courts.

But staff in the royal household were specifically prevented from doing so, although the wording of the ban was sufficiently vague that the public might not have realised the monarch’s staff had been exempted.

A civil servant noted that the exemption in the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act had been “acceptable to the palace, largely because it did not explicitly single out persons employed by Her Majesty in her personal capacity for special exception” while still removing them from its scope.

The exemption was extended to the present day when in 2010 the Equality Act replaced the 1976 Race Relations Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1970 Equal Pay Act. For many years, critics have regularly pointed out that the royal household employed few black, Asian or minority-ethnic people.

In 1990 the journalist Andrew Morton reported in the Sunday Times that “a black face has never graced the executive echelons of royal service – the household and officials” and “even among clerical and domestic staff, there is only a handful of recruits from ethnic minorities”.

The following year, the royal researcher Philip Hall published a book, Royal Fortune, in which he cited a source close to the Queen confirming that there were no non-white courtiers in the palace’s most senior ranks.

In 1997 the Palace admitted to the Independent that it was not carrying out an officially recommended policy of monitoring staff numbers to ensure equal opportunities.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson said: “The royal household and the sovereign comply with the provisions of the Equality Act, in principle and in practice. This is reflected in the diversity, inclusion and dignity at work policies, procedures and practices within the royal household.

“Any complaints that might be raised under the act follow a formal process that provides a means of hearing and remedying any complaint.” The palace did not respond when asked if the monarch was subject to this act in law.

The documents also shed light on how Buckingham Palace negotiated controversial clauses – that remain in place to this day – exempting the Queen and her household from laws that prevent race and sex discrimination.

The papers were discovered at the National Archives as part of the Guardian’s ongoing investigation into the royal family’s use of an arcane parliamentary procedure, known as Queen’s consent, to secretly influence the content of British laws.

They reveal how in 1968, the Queen’s chief financial manager informed civil servants that “it was not, in fact, the practice to appoint coloured immigrants or foreigners” to clerical roles in the royal household, although they were permitted to work as domestic servants.

It is unclear when the practice ended. Buckingham Palace refused to answer questions about the ban and when it was revoked. It said its records showed people from ethnic minority backgrounds being employed in the 1990s. It added that before that decade, it did not keep records on the racial backgrounds of employees.

Exemptions from the law

In the 1960s government ministers sought to introduce laws that would make it illegal to refuse to employ an individual on the grounds of their race or ethnicity.

The Queen has remained personally exempted from those equality laws for more than four decades. The exemption has made it impossible for women or people from ethnic minorities working for her household to complain to the courts if they believe they have been discriminated against.

In a statement, Buckingham Palace did not dispute that the Queen had been exempted from the laws, adding that it had a separate process for hearing complaints related to discrimination. The palace did not respond when asked what this process consists of.

The exemption from the law was brought into force in the 1970s, when politicians implemented a series of racial and sexual equality laws to eradicate discrimination.

The official documents reveal how government officials in the 1970s coordinated with Elizabeth Windsor’s advisers on the wording of the laws.

The documents are likely to refocus attention on the royal family’s historical and current relationship with race.

Much of the family’s history is inextricably linked with the British empire, which subjugated people around the world. Some members of the royal family have also been criticised for their racist comments.

In March the Duchess of Sussex, the family’s first mixed-race member, said she had had suicidal thoughts during her time in the royal family, and alleged that a member of the family had expressed concern about her child’s skin colour.

The allegation compelled her brother-in-law, Prince William, to declare that the royal family was “very much not” racist.

Queen’s consent

Some of the documents uncovered by the Guardian relate to the use of Queen’s consent, an obscure parliamentary mechanism through which the monarch grants parliament permission to debate laws that affect her and her private interests.

Buckingham Palace says the process is a mere formality, despite compelling evidence that the Queen has repeatedly used the power to secretly lobby ministers to amend legislation she does not like.

The newly discovered documents reveal how the Queen’s consent procedure was used to secretly influence the formation of the draft race relations legislation.

In 1968, the then home secretary, James Callaghan, and civil servants at the Home Office appear to have believed that they should not request Queen’s consent for parliament to debate the race relations bill until her advisers were satisfied it could not be enforced against her in the courts.

At the time, Callaghan wanted to expand the UK’s racial discrimination laws, which only prohibited discrimination in public places, so that they also prevented racism in employment or services such as housing.

A key proposal of the bill was the Race Relations Board, which would act as an ombudsman for discrimination complaints and could bring court proceedings against individuals or companies that maintained racist practices.

‘Not the practice to appoint coloured immigrants’

In February 1968, a Home Office civil servant, TG Weiler, summarised the progress of discussions with Lord Tryon, the keeper of the privy purse, who was responsible for managing the Queen’s finances, and other courtiers.

Tryon, he wrote, had informed them Buckingham Palace was prepared to comply with the proposed law, but only if it enjoyed similar exemptions to those provided to the diplomatic service, which could reject job applicants who had been resident in the UK for less than five years.

According to Weiler, Tryon considered staff in the Queen’s household to fall into one of three types of roles: “(a) senior posts, which were not filled by advertising or by any overt system of appointment and which would presumably be accepted as outside the scope of the bill; (b) clerical and other office posts, to which it was not, in fact, the practice to appoint coloured immigrants or foreigners; and (c) ordinary domestic posts for which coloured applicants were freely considered, but which would in any event be covered by the proposed general exemption for domestic employment.”

“They were particularly concerned,” Weiler wrote, “that if the proposed legislation applied to the Queen’s household it would for the first time make it legally possible to criticise the household. Many people do so already, but this has to be accepted and is on a different footing from a statutory provision.”

By March, Buckingham Palace was satisfied with the proposed law. A Home Office official noted that the courtiers “agreed that the way was now open for the secretary of state to seek the Queen’s consent to place her interest at the disposal of parliament for the purpose of the bill.”

The phrasing of the documents is highly significant, because it suggests that Callaghan and the Home Office officials believed it might not be possible to obtain the Queen’s consent for parliament to debate the racial equality law unless the monarch was assured of her exemption.

As a result of this exemption, the Race Relations Board that was given the task of investigating racial discrimination would send any complaints from the Queen’s staff to the home secretary rather than the courts.

In the 1970s, the government brought in three laws to counter racial and sexual discrimination in the workplace. Complainants in general were empowered to take their cases directly to the courts.

But staff in the royal household were specifically prevented from doing so, although the wording of the ban was sufficiently vague that the public might not have realised the monarch’s staff had been exempted.

A civil servant noted that the exemption in the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act had been “acceptable to the palace, largely because it did not explicitly single out persons employed by Her Majesty in her personal capacity for special exception” while still removing them from its scope.

The exemption was extended to the present day when in 2010 the Equality Act replaced the 1976 Race Relations Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1970 Equal Pay Act. For many years, critics have regularly pointed out that the royal household employed few black, Asian or minority-ethnic people.

In 1990 the journalist Andrew Morton reported in the Sunday Times that “a black face has never graced the executive echelons of royal service – the household and officials” and “even among clerical and domestic staff, there is only a handful of recruits from ethnic minorities”.

The following year, the royal researcher Philip Hall published a book, Royal Fortune, in which he cited a source close to the Queen confirming that there were no non-white courtiers in the palace’s most senior ranks.

In 1997 the Palace admitted to the Independent that it was not carrying out an officially recommended policy of monitoring staff numbers to ensure equal opportunities.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson said: “The royal household and the sovereign comply with the provisions of the Equality Act, in principle and in practice. This is reflected in the diversity, inclusion and dignity at work policies, procedures and practices within the royal household.

“Any complaints that might be raised under the act follow a formal process that provides a means of hearing and remedying any complaint.” The palace did not respond when asked if the monarch was subject to this act in law.

By March, Buckingham Palace was satisfied with the proposed law. A Home Office official noted that the courtiers “agreed that the way was now open for the secretary of state to seek the Queen’s consent to place her interest at the disposal of parliament for the purpose of the bill.”

The phrasing of the documents is highly significant, because it suggests that Callaghan and the Home Office officials believed it might not be possible to obtain the Queen’s consent for parliament to debate the racial equality law unless the monarch was assured of her exemption.

As a result of this exemption, the Race Relations Board that was given the task of investigating racial discrimination would send any complaints from the Queen’s staff to the home secretary rather than the courts.

In the 1970s, the government brought in three laws to counter racial and sexual discrimination in the workplace. Complainants in general were empowered to take their cases directly to the courts.

But staff in the royal household were specifically prevented from doing so, although the wording of the ban was sufficiently vague that the public might not have realised the monarch’s staff had been exempted.

A civil servant noted that the exemption in the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act had been “acceptable to the palace, largely because it did not explicitly single out persons employed by Her Majesty in her personal capacity for special exception” while still removing them from its scope.

The exemption was extended to the present day when in 2010 the Equality Act replaced the 1976 Race Relations Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1970 Equal Pay Act. For many years, critics have regularly pointed out that the royal household employed few black, Asian or minority-ethnic people.

In 1990 the journalist Andrew Morton reported in the Sunday Times that “a black face has never graced the executive echelons of royal service – the household and officials” and “even among clerical and domestic staff, there is only a handful of recruits from ethnic minorities”.

The following year, the royal researcher Philip Hall published a book, Royal Fortune, in which he cited a source close to the Queen confirming that there were no non-white courtiers in the palace’s most senior ranks.

In 1997 the Palace admitted to the Independent that it was not carrying out an officially recommended policy of monitoring staff numbers to ensure equal opportunities.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson said: “The royal household and the sovereign comply with the provisions of the Equality Act, in principle and in practice. This is reflected in the diversity, inclusion and dignity at work policies, procedures and practices within the royal household.

“Any complaints that might be raised under the act follow a formal process that provides a means of hearing and remedying any complaint.” The palace did not respond when asked if the monarch was subject to this act in law.

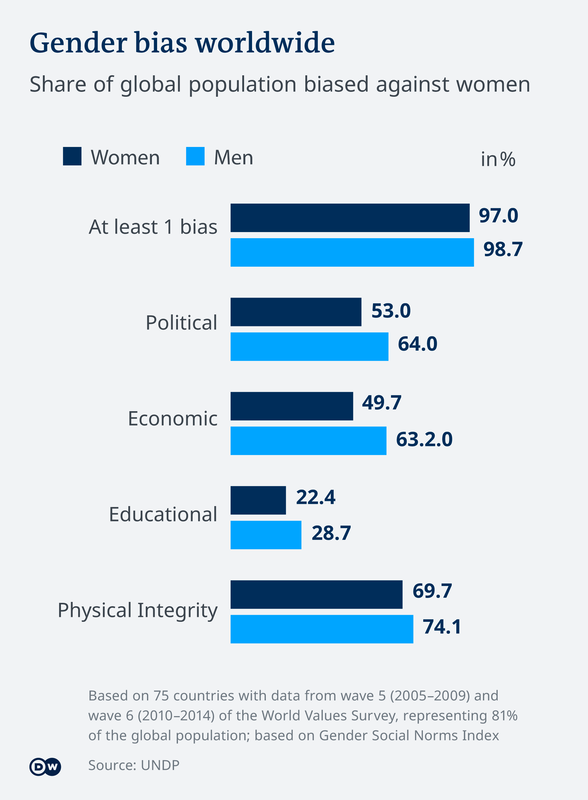

Gender equality: Most people are biased against women, UN says

A new study shows that almost 90% of people worldwide are biased against women and around half perceive men to make better leaders. And nearly 30% of people think it's justified for a husband to beat his wife.

dw.com

3/5/2020

Women around the world still suffer from widespread gender bias, according to a newly-published report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

The study measures how people's social beliefs inhibit gender equality in areas including education, politics and the work force. It contains data from 75 countries, covering over 80% of the world's population.

Pedro Conceicao, director of the Human Development Report Office at UNDP, said that while progress has been made in giving women the same access to basic needs as men in education and health, gender gaps remain in areas "that challenge power relations and are most influential in actually achieving true equality."

The UNDP analysis found that despite decades-long efforts to close the gender divide, around half of the world's population feel that men make better political leaders, while over 40% think men make better business executives and have more right to a job when work availability is limited. Almost 30% of people think it's justified for a husband to beat his wife.

Women hold only 24% of parliamentary seats globally and they make up less than 6% of chief executives in S&P 500 companies, the study showed.

Countries with the highest numbers of people showing any kind of bias against gender equality are Jordan, Qatar, Nigeria, Pakistan and Zimbabwe. The countries with the lowest levels of gender bias are Andorra, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

The study measures how people's social beliefs inhibit gender equality in areas including education, politics and the work force. It contains data from 75 countries, covering over 80% of the world's population.

Pedro Conceicao, director of the Human Development Report Office at UNDP, said that while progress has been made in giving women the same access to basic needs as men in education and health, gender gaps remain in areas "that challenge power relations and are most influential in actually achieving true equality."

The UNDP analysis found that despite decades-long efforts to close the gender divide, around half of the world's population feel that men make better political leaders, while over 40% think men make better business executives and have more right to a job when work availability is limited. Almost 30% of people think it's justified for a husband to beat his wife.

Women hold only 24% of parliamentary seats globally and they make up less than 6% of chief executives in S&P 500 companies, the study showed.

Countries with the highest numbers of people showing any kind of bias against gender equality are Jordan, Qatar, Nigeria, Pakistan and Zimbabwe. The countries with the lowest levels of gender bias are Andorra, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden.

Women Perform 12.5 Billion Hours of Unpaid Labor Every Day

BY Michelle Chen, Truthout

PUBLISHED January 24, 2020

The global economy is polarized on multiple dimensions. Even as the gap widens between the extremely poor and ultra-rich, a chronic economic divide persists between men and women. Millions of people subsist on an income of a few dollars a day, and billions of women work for nothing at all.

Oxfam’s new report on global inequality — which was released to coincide with the gathering of the ultra-wealthy at the World Economic Forum January 21-24 in Davos, Switzerland — lays out devastating but familiar, statistics: The world has 2,153 billionaires who collectively possess more wealth than 4.6 billion people at the bottom of the income scale. More than half the world’s population is estimated to survive on less than $5.50 a day, while the rate of poverty reduction slowed by half since 2013.

The latest analysis highlights how poverty is both gendered and also socially entrenched. According to the report, men collectively own 50 percent more wealth than women do, and at the top of that wealth gap, “the richest 22 men in the world own more wealth than all the women in Africa.”

The gender wealth gap isn’t entirely surprising — sexism predates industrial capitalism, after all. But the systematic economic subjugation of women reflects how patriarchy and poverty are mutually reinforcing. Due to social as well as cultural pressure, women perform vast amounts of unpaid labor — about 12.5 billion hours every day.

Women’s unwaged labor — which occupies up to 14 hours a day in rural and low-income regions — involves domestic duties, primarily the “care work” of looking after children or elders, cooking, cleaning and mending. It could also involve procuring water or gathering firewood, or tending subsistence crops on a family farm — tasks that will become increasingly challenging as climate change and other environmental stresses intensify.

One woman in rural India, who said she worked around the clock and would be beaten by her husband if she slipped up, told Oxfam researchers, “I have no time, not even time to die for they will all curse…. Who will look after them and bring money to the family when I’m gone?”

If women like her were paid the real value of their economic contributions to their families, they would be owed at least $10.8 trillion (more than half of the U.S. annual gross domestic product) — the estimated collective value of women’s unpaid care work worldwide.

“The care economy is very neglected,” said Gawain Kripke, director of policy and research at Oxfam America. “Most of it is unpaid. And what we pay [for] is treated very poorly. And this provides a subsidy to the more formal economy. All this work that gets done, society and the economy wouldn’t function without this work…. Businesses rely on it, families rely on it, society as a whole relies on it. And yet we don’t recognize it, and don’t compensate it, and don’t support it.”

This is not an accidental oversight, but institutionalized oppression. “This is what patriarchy is,” he added. “It ignores and makes invisible women, and exalts and elevates rich men.”

In the United States, the care gap for children and the elderly falls disproportionately on women, whether they are caring for their own, or paid as hired care workers. In 2018, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, about 16.2 million people, the majority of them women, provided unpaid informal care for individuals with dementia, contributing about 18.5 billion hours of feeding, bathing, providing medication and other tasks. If the unpaid care work in the U.S. was provided through government services instead, taxpayers would have paid an estimated $234 billion. Meanwhile, professional home health care aides who care for seniors — aides who are also mostly women — typically earn poverty wages, and about half receive public benefits.

Child care faces a similar crisis: it’s both extremely expensive for families — well over $1,000 per month in many areas — and chronically underpaid for child care providers. Across the country, the Center for American Progress reports that roughly half of families with children under the age of six (about 6.3 million households) face difficulty finding suitable child care, often because of cost barriers or a lack of open slots. Roughly 4 in 10 mothers (and an even higher percentage of Black and Latinx women) are especially vulnerable because they are the primary or sole income-earners for their families. Women who could not find a decent child care program were generally less likely to be employed (fathers’ workforce participation, unsurprisingly, did not change according to child care availability), indicating that many women opt out of work rather than have their earnings eaten up by daycare fees.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) Chief Operating Officer Cynthia Hess says that, since women tend to earn lower wages, “it often makes economic sense for the family for the woman to be the one to do that…. And without access to that affordable quality child care, a lot of working parents, particularly mothers, really don’t have a real choice about whether to participate in the paid labor force or not.”

According to Wendy Chun-Hoon, executive director of advocacy group Family Values @ Work, the marginalization of care work can drag down women’s lifetime economic prospects. “Devaluing women means care work is under-valued and unseen. That leads to lower pay and to job loss, which then cements women in jobs that pay less and have less opportunity for advancement, or boots women out of the workforce and labels them as ‘unreliable’ and ‘dependent’,” Chun-Hoon told Truthout via email.

Despite steady growth in women’s workforce participation over the past 50 years, the care gap between working men and women has barely budged. According to the Pew Research Center’s time-survey analysis from 1965 to 2011, “American mothers still spend about twice as much time with their children as fathers” — with women most recently clocking around 13.5 hours a week, compared to men’s 7.3 hours. According to a briefing paper co-authored by Oxfam America and IWPR, the care gap is wider among young people than older ones: Women aged 25 to 34 spend about twice as much time on unpaid household and care work (8 hours to 3.9 hours) than their male peers, compared to a gap of 5.6 hours per week versus 4.1 hours per week between women and men aged 45 to 54. The care gap is also wider between Black, Latinx and Asian men and women than between white ones.

The gender gap in wealth is undergirded by a gender gap in political power. The inequality report points out that fewer than one in four government ministers around the world is a woman, which might explain why the social welfare policies most crucial to women and families are often targeted by austerity measures. “Cutting these services is done as a budget savings,” Kripke said, “but they don’t see that the costs will be borne mainly by women, and many women will have to leave the paid workforce in order to pick up the care burdens.”

Although the intersection of gender and economic inequality is built into most modern social structures today, Oxfam and IWPR researchers note that both gender and economic justice can be tackled in tandem through the structural redistribution of wealth. For the U.S., gender-equality advocates recommend measures like paid family leave and paid sick days to allow working parents to meet their care needs without endangering their jobs. The gender wage gap, which hovers at roughly 19 percent between women’s and men’s weekly earnings, could be narrowed by boosting wages and working conditions and supporting collective bargaining. To help counter gender stereotypes, paid family leave policies should be structured to encourage men to use their leave time to spend more time caring for their kids.

In the U.S., child care has become a central issue for both liberal and conservative lawmakers. Democratic presidential contenders Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have advocated for universal early childhood education funded through a wealth tax. Warren has proposed making child care free for households earning less than double the federal poverty line and cap overall costs at 7 percent of income; Sanders has not released a detailed plan, but has called for universal preschool, in line with legislation he previously sponsored. Sanders also commented broadly on the Oxfam report, stating that the global wealth gap had pointed to the need to “develop an international movement that takes on the greed of the billionaire class.”

In response to the Oxfam report, Mary Ignatius, statewide organizer of the California-based advocacy group Parent Voices, stated, “Fully funding a robust and comprehensive child care system that meets the needs of today’s working women will dramatically and immediately close the income inequality crisis in this country and liberate women to take greater control of their lives.”

At the same time, a robust national family care program would engage women both as beneficiaries and workers. Although care jobs are hugely in demand, they remain notoriously low-paying and underregulated. A sustainable care infrastructure — expanding on the model family welfare policies of Scandinavian countries — would guarantee living wage jobs in gender-segregated sectors of the economy — particularly child care and home care jobs that relegate millions of women to the lowest wage tiers of the education and health care systems. An analysis by the University of California-Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment shows that aligning preschool teachers’ salaries with those of typical elementary and middle school teachers would more than double their pay, from $25,218 to $60,602 annually, which, multiplied by the early childhood education workforce nationwide, would boost their collective earnings by more than $80 billion. Similarly, the home health care workforce, with annual median wages stuck at just $13,000, would be massively boosted by raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour, which would in turn raise their income by roughly 50 percent, and generate an economic ripple effect that would average $2,000 per worker.

The Oxfam report estimates that taxing just an additional half of 1 percent of the wealth of the richest people in the U.S. would, over a decade, generate the funds “needed to create 117 million care jobs in education, health and elderly care and other sectors, and to close care deficits.” Those jobs could form the foundation of a comprehensive care-labor infrastructure, providing working parents with universal access to child, elder and disability care, as well as the flexibility to take time off from work to tend to an ailing parent or bond with a newborn, without risking their families’ economic security.

Global inequality, of course, is not just a gender issue. But the current inequities in wealth around the world could not exist if patriarchy were not subordinating half the population to a hierarchy within a hierarchy. And to end inequality, a political transformation that dismantles sexism as a tool of economic oppression is a critical step toward total social emancipation.

Oxfam’s new report on global inequality — which was released to coincide with the gathering of the ultra-wealthy at the World Economic Forum January 21-24 in Davos, Switzerland — lays out devastating but familiar, statistics: The world has 2,153 billionaires who collectively possess more wealth than 4.6 billion people at the bottom of the income scale. More than half the world’s population is estimated to survive on less than $5.50 a day, while the rate of poverty reduction slowed by half since 2013.

The latest analysis highlights how poverty is both gendered and also socially entrenched. According to the report, men collectively own 50 percent more wealth than women do, and at the top of that wealth gap, “the richest 22 men in the world own more wealth than all the women in Africa.”

The gender wealth gap isn’t entirely surprising — sexism predates industrial capitalism, after all. But the systematic economic subjugation of women reflects how patriarchy and poverty are mutually reinforcing. Due to social as well as cultural pressure, women perform vast amounts of unpaid labor — about 12.5 billion hours every day.

Women’s unwaged labor — which occupies up to 14 hours a day in rural and low-income regions — involves domestic duties, primarily the “care work” of looking after children or elders, cooking, cleaning and mending. It could also involve procuring water or gathering firewood, or tending subsistence crops on a family farm — tasks that will become increasingly challenging as climate change and other environmental stresses intensify.

One woman in rural India, who said she worked around the clock and would be beaten by her husband if she slipped up, told Oxfam researchers, “I have no time, not even time to die for they will all curse…. Who will look after them and bring money to the family when I’m gone?”

If women like her were paid the real value of their economic contributions to their families, they would be owed at least $10.8 trillion (more than half of the U.S. annual gross domestic product) — the estimated collective value of women’s unpaid care work worldwide.

“The care economy is very neglected,” said Gawain Kripke, director of policy and research at Oxfam America. “Most of it is unpaid. And what we pay [for] is treated very poorly. And this provides a subsidy to the more formal economy. All this work that gets done, society and the economy wouldn’t function without this work…. Businesses rely on it, families rely on it, society as a whole relies on it. And yet we don’t recognize it, and don’t compensate it, and don’t support it.”

This is not an accidental oversight, but institutionalized oppression. “This is what patriarchy is,” he added. “It ignores and makes invisible women, and exalts and elevates rich men.”

In the United States, the care gap for children and the elderly falls disproportionately on women, whether they are caring for their own, or paid as hired care workers. In 2018, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, about 16.2 million people, the majority of them women, provided unpaid informal care for individuals with dementia, contributing about 18.5 billion hours of feeding, bathing, providing medication and other tasks. If the unpaid care work in the U.S. was provided through government services instead, taxpayers would have paid an estimated $234 billion. Meanwhile, professional home health care aides who care for seniors — aides who are also mostly women — typically earn poverty wages, and about half receive public benefits.

Child care faces a similar crisis: it’s both extremely expensive for families — well over $1,000 per month in many areas — and chronically underpaid for child care providers. Across the country, the Center for American Progress reports that roughly half of families with children under the age of six (about 6.3 million households) face difficulty finding suitable child care, often because of cost barriers or a lack of open slots. Roughly 4 in 10 mothers (and an even higher percentage of Black and Latinx women) are especially vulnerable because they are the primary or sole income-earners for their families. Women who could not find a decent child care program were generally less likely to be employed (fathers’ workforce participation, unsurprisingly, did not change according to child care availability), indicating that many women opt out of work rather than have their earnings eaten up by daycare fees.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR) Chief Operating Officer Cynthia Hess says that, since women tend to earn lower wages, “it often makes economic sense for the family for the woman to be the one to do that…. And without access to that affordable quality child care, a lot of working parents, particularly mothers, really don’t have a real choice about whether to participate in the paid labor force or not.”

According to Wendy Chun-Hoon, executive director of advocacy group Family Values @ Work, the marginalization of care work can drag down women’s lifetime economic prospects. “Devaluing women means care work is under-valued and unseen. That leads to lower pay and to job loss, which then cements women in jobs that pay less and have less opportunity for advancement, or boots women out of the workforce and labels them as ‘unreliable’ and ‘dependent’,” Chun-Hoon told Truthout via email.

Despite steady growth in women’s workforce participation over the past 50 years, the care gap between working men and women has barely budged. According to the Pew Research Center’s time-survey analysis from 1965 to 2011, “American mothers still spend about twice as much time with their children as fathers” — with women most recently clocking around 13.5 hours a week, compared to men’s 7.3 hours. According to a briefing paper co-authored by Oxfam America and IWPR, the care gap is wider among young people than older ones: Women aged 25 to 34 spend about twice as much time on unpaid household and care work (8 hours to 3.9 hours) than their male peers, compared to a gap of 5.6 hours per week versus 4.1 hours per week between women and men aged 45 to 54. The care gap is also wider between Black, Latinx and Asian men and women than between white ones.

The gender gap in wealth is undergirded by a gender gap in political power. The inequality report points out that fewer than one in four government ministers around the world is a woman, which might explain why the social welfare policies most crucial to women and families are often targeted by austerity measures. “Cutting these services is done as a budget savings,” Kripke said, “but they don’t see that the costs will be borne mainly by women, and many women will have to leave the paid workforce in order to pick up the care burdens.”

Although the intersection of gender and economic inequality is built into most modern social structures today, Oxfam and IWPR researchers note that both gender and economic justice can be tackled in tandem through the structural redistribution of wealth. For the U.S., gender-equality advocates recommend measures like paid family leave and paid sick days to allow working parents to meet their care needs without endangering their jobs. The gender wage gap, which hovers at roughly 19 percent between women’s and men’s weekly earnings, could be narrowed by boosting wages and working conditions and supporting collective bargaining. To help counter gender stereotypes, paid family leave policies should be structured to encourage men to use their leave time to spend more time caring for their kids.

In the U.S., child care has become a central issue for both liberal and conservative lawmakers. Democratic presidential contenders Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have advocated for universal early childhood education funded through a wealth tax. Warren has proposed making child care free for households earning less than double the federal poverty line and cap overall costs at 7 percent of income; Sanders has not released a detailed plan, but has called for universal preschool, in line with legislation he previously sponsored. Sanders also commented broadly on the Oxfam report, stating that the global wealth gap had pointed to the need to “develop an international movement that takes on the greed of the billionaire class.”

In response to the Oxfam report, Mary Ignatius, statewide organizer of the California-based advocacy group Parent Voices, stated, “Fully funding a robust and comprehensive child care system that meets the needs of today’s working women will dramatically and immediately close the income inequality crisis in this country and liberate women to take greater control of their lives.”

At the same time, a robust national family care program would engage women both as beneficiaries and workers. Although care jobs are hugely in demand, they remain notoriously low-paying and underregulated. A sustainable care infrastructure — expanding on the model family welfare policies of Scandinavian countries — would guarantee living wage jobs in gender-segregated sectors of the economy — particularly child care and home care jobs that relegate millions of women to the lowest wage tiers of the education and health care systems. An analysis by the University of California-Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment shows that aligning preschool teachers’ salaries with those of typical elementary and middle school teachers would more than double their pay, from $25,218 to $60,602 annually, which, multiplied by the early childhood education workforce nationwide, would boost their collective earnings by more than $80 billion. Similarly, the home health care workforce, with annual median wages stuck at just $13,000, would be massively boosted by raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour, which would in turn raise their income by roughly 50 percent, and generate an economic ripple effect that would average $2,000 per worker.

The Oxfam report estimates that taxing just an additional half of 1 percent of the wealth of the richest people in the U.S. would, over a decade, generate the funds “needed to create 117 million care jobs in education, health and elderly care and other sectors, and to close care deficits.” Those jobs could form the foundation of a comprehensive care-labor infrastructure, providing working parents with universal access to child, elder and disability care, as well as the flexibility to take time off from work to tend to an ailing parent or bond with a newborn, without risking their families’ economic security.

Global inequality, of course, is not just a gender issue. But the current inequities in wealth around the world could not exist if patriarchy were not subordinating half the population to a hierarchy within a hierarchy. And to end inequality, a political transformation that dismantles sexism as a tool of economic oppression is a critical step toward total social emancipation.

review

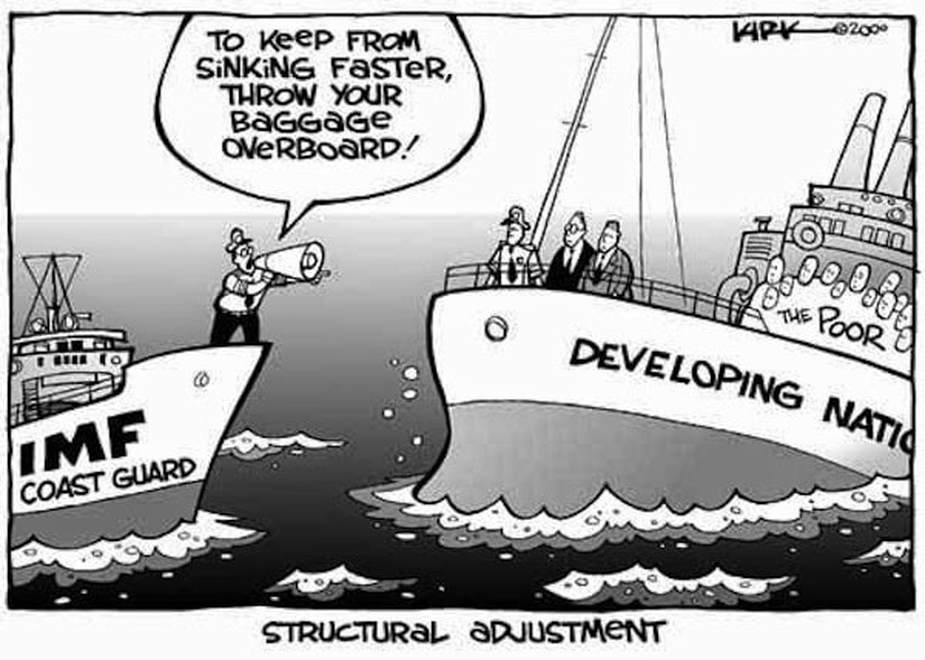

Here’s What Workers of the Global South Endure to Create Corporate Wealth

BY Eve Ottenberg, Truthout

PUBLISHED January 5, 2020

In recent decades, as U.S. corporations shipped millions of jobs overseas to save money on wages, GM, H&M, Apple and dozens of other companies established elaborate supply chains in Asia, Mexico and Latin America, where workers earn pennies per hour. These chains are geographically expansive networks organized by foreign companies to produce semi-finished goods in different places before final assembly for huge global corporations.

Abuses abound. One typical example: An Indonesian factory that supplied the Japanese multinational behind the clothing brand Uniqlo abruptly closed, leaving workers with unpaid wages and unpaid severance. Intan Suwandi, the author of the recently published book Value Chains, told Truthout that there have been similar cases involving Nike, Adidas, H&M and Walmart in Cambodia and Honduras. A Chinese factory that supplied PUMA abused its workers and paid starvation wages, while workers in India’s home garment sector are as young as 10 years old, working for companies that supply the U.S. and European Union.

Suwandi also cites, in an email, a Chinese factory that produces computer products, such as keyboards and printer cases, for Hewlitt-Packard, Dell, Lenovo, Microsoft and IBM. The factory applied a “long list of draconian disciplinary measures, and fines were used to control every movement and almost every second of the workers’ lives.” She also mentions a Chinese factory that produces parts for Ford, where, among many violations, seriously injured workers were “fired after a year or two.”

And then there’s Foxconn, the Taiwanese company that assembles iPhones for Apple and products for Dell, Nokia, Hewlitt-Packard and Sony. It employs roughly 400,000 people at its Shenzhen factory, paying 83 cents an hour, under conditions so deplorable that in one six-month period in 2010, 13 workers jumped from the factory building, at least 10 to their deaths, while later, 150 threatened to kill themselves thus. Meanwhile, in 2012, a fire in a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, that supplied Walmart and Sears, killed 112 workers.

Value Chains argues that economic imperialism is alive and well and being practiced in the Global South by corporations from the North. Although in recent years some leftists have argued that with the hollowing out of the Global North’s manufacturing base, economic imperialism ended, Suwandi disputes this. Her book mentions the GM commodity chain, which, as former GM director of sustainability David Tulauskas told Suwandi, includes “20,000 suppliers that provide us parts that go onto our vehicles. We buy from them approximately 200,000 individual items, spending about $100 billion. We operate in 30 countries. We sell those products in 125 countries.” Those suppliers, Suwandi explains, are scattered in Brazil, China and Mexico. Wages are kept low through direct investments and “arm’s lengths contracts.”

Value Chains devotes many pages to these contracts, which are a form of subcontracting without equity involvement. In these contracts, multinationals outsource production to suppliers mostly in the global South through contract relationships. As a result, the complex network of labor-value chains conceals how profits are extracted from workers by making it almost impossible to trace profits back to those workers. This is largely due to the arm’s length contracts.

Suwandi cites John Smith’s Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century in order to demonstrate how much wealth transnational western corporations extract from workers in the Global South: “Apple subcontracts the production of the component parts of its iPhones to a number of countries, with Foxconn subcontracting the final assembly in China. Due … to low-end wages … Apple’s gross profit margin on its iPhone 4 in 2010 was found to be 59 percent of the final sales price.” For each iPhone 4, retailing at $549, Smith writes, only $10 went to labor costs in China.

Cheap labor in the Global South means that multinational capital only has to pay a few cents an hour for work which creates much more value than that, Suwandi explains. Corporations disguise this value capture by attributing it to marketing, distribution and design activities in the Global North. Of course, it helps that that’s where the products are sold, with high markups on production cost. This obfuscates GDP. Take Apple’s iPhones:

Only 1.8 percent goes to labor costs in China, only that amount is recorded in China’s GDP, while a large percentage is recorded in the GDP of the country where Apple is headquartered — the United States — even when none of the production processes happened here…. The country where the iPhone was produced receives in its GDP only a small proportion of the final sales price. Meanwhile the larger part shows up in the GDP of the country where it is consumed…. So that’s why the profits that multinationals get are very difficult to trace back to the workers in the Global South.

Suwandi emails that global labor value chains (or “global commodity chains,” “global value chains,” or “global supply chains”) link people, tools and activities to deliver goods and services to the market. Her book argues that multinational corporations headquartered in the Global North control these chains completely, in every detail, even though they don’t own them. She explains that each chain consists of various nodes (each node signifies a specific production process) with different businesses involved in these different production processes. Take a pair of Nike sneakers: Several nodes are involved where semi-finished parts of the final product are made in various factories located in different countries. The raw materials are also acquired from different countries. If final assembly occurs in a factory in Vietnam, the sneakers will be labeled “made in Vietnam.”

The top three countries participating in labor value chains are China, India and Indonesia, where, according to Value Chains, wages are low and productivity is high. These labor value chains “are imperialistic in their characteristics,” because “capital accumulation processes are inseparable from the unequal relations among nation states.” The global labor force is concentrated in the South: With 541 million industrial workers there in 2010, compared to 145 million in the North, the idea that the commodity chain system is imperialist in nature makes sense. Indeed, Value Chains argues that globalized production is a new form of economic imperialism that transfers wealth from South to North. This does not preclude, however, the creation of local billionaires in China and India, who reap immense profits from their own transnational corporations. And where does all that profit go? “Huge quantities of this loot,” Value Chains reports, “captured from peripheral economies in the global South end up in the ‘treasure islands’ of the Caribbean, where trillions of dollars of money capital are now deposited.”

All this pelf, of course, comes directly out of workers’ hides. The cheaper the wages of the workers in the Global South, the greater the gross profit margins. Moreover, Suwandi explains, “Multinationals exercise a high degree of control within these labor-value chains, even when they only engage in contractual relationships with their suppliers.”

Value Chains examines two Indonesian firms, pseudonymously labeled Java Film and Star Inc., which often have the same customers for the plastic wrappers they produce. These firms do not use sweatshops, partly because they do not identify as “labor intensive.” But that’s one of Suwandi’s points: Exploitation does not necessarily involve blatantly abusive practices. She observes that multinationals control their suppliers’ production to the smallest detail, determining their suppliers’ profit margins, by increasing exploitation of the suppliers’ workers, usually through increased productivity, but also sometimes by depriving workers of their rights, or through violence, abuse and law-breaking.

Making production more economical and increasing productivity involve two processes, according to Value Chains – “systemic rationalization and flexible production.” Suwandi explains that capital wants production to be flexible enough to accommodate market fluctuations, “without paying the price … this burden is in the end placed upon workers through enhancing exploitation.” Engaging in arm’s length contracts itself exemplifies both processes. Systemic rationalization, according to Value Chains, refers “to the technological and organizational changes by corporations that began in the 1970s … [with] its focus on the rise of decentralized production throughout the globe.” (The ‘70s was the decade when neoliberalism and the union busting it entailed really got going. It’s when corporations “modernized.”) Flexible production — according to Lean and Mean by Bennett Harrison, which Value Chains quotes — involves “lean production, downsizing, outsourcing and the growing importance of spatially extensive production networks governed by powerful core firms and their strategic allies.”