TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

Discussions on civil rights and race

april 2024

"White people in North America live in a social environment that protects and insulates them from race-based stress. This insulated environment of racial protection builds white expectations for racial comfort while at the same time lowering the ability to tolerate racial stress, leading to what I refer to as White Fragility. White Fragility is a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include the outward display of emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence, and leaving the stress-inducing situation. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium."

Robin DiAngelo, Ph.D

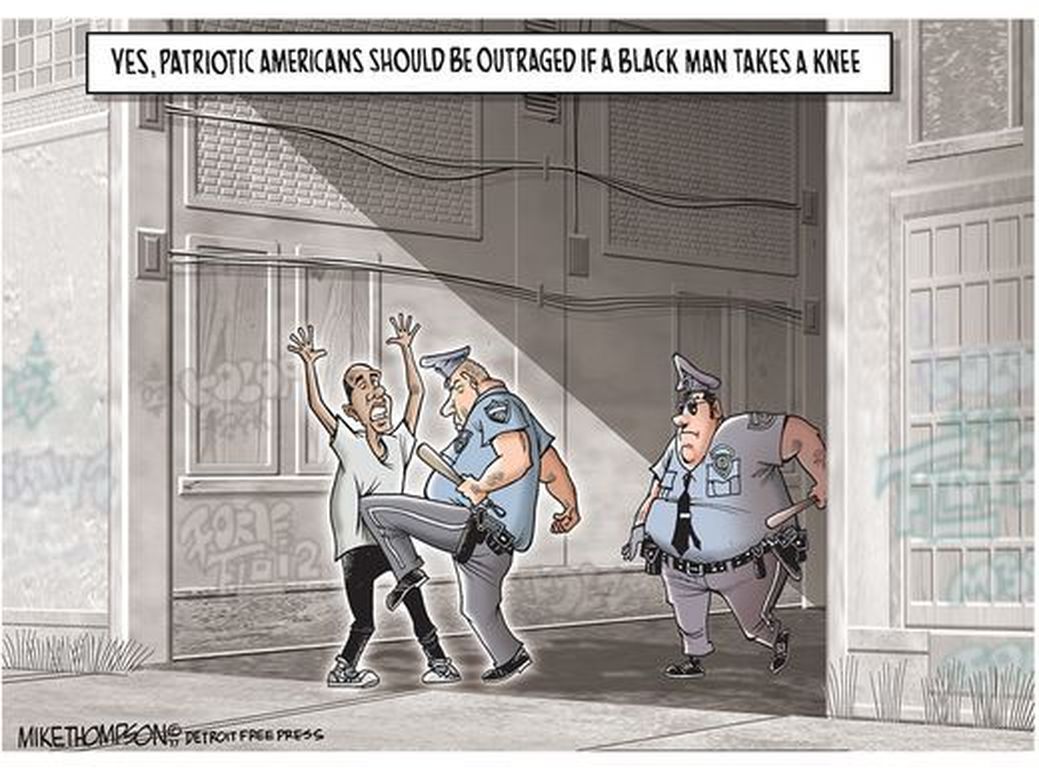

What people don't like is black people protesting against racism

at some point people should be honest and admit what they don't like is black people protesting against oppression and racism, and quit pretending that what they are sincerely against are the tactics used. Kaepernick used the quietest protest ever and people are flipping out, and BLM uses loud protests and people flip out. It's not the tactics that people are against, it's the goddamn message.

People should quit lying to themselves and to others.

Ken Burns: "We were founded on the idea that all men were created equal, but oops—the guy who wrote that owned more than 100 human beings and didn’t see in his lifetime to free any one of them; didn’t see the contradiction or the hypocrisy. And so it set us on a journey where we are constantly having to struggle not with race, but racism."

race did come from science and theology; it came to science and theology. racial ideas were born in the colonial world, in the brutal and deadly processes of empire building....

by craig steven wilder

ebony and ivy

RACE, CULTURAL CONSTRUCT BASED ON THE POPULAR, BUT MISTAKEN NOTION THAT HUMANS CAN BE DIVIDED INTO BIOLOGICALLY DISTINCT CATEGORIES BY MEANS OF PARTICULAR PHYSICAL FEATURES SUCH AS SKIN COLOR, HEAD SHAPE, AND OTHER VISIBLE TRAITS THAT ARE TRANSMISSIBLE BY DESCENT...GENERIC STUDIES UNDERTAKEN IN THE LAST DECADES OF THE 20TH CENTURY CONFIRM THAT "RACES" DO NOT EXIST IN ANY BIOLOGICAL SENSE.

ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, 2002

...There are a number of racist types floating around, like the I’m Not a Racist racists. Think of the guy who says “I’m not racist” every time he justifies mass incarceration and police murders. He doesn’t identify as a racist because he talks to black people in public places, loves professional sports like the NBA and NFL, which are dominated by black athletes, and is totally okay with black people until they bring up race or question his privilege. And then we have the I Don’t Know That I’m a Racist racists. This is the guy who doesn’t think he’s a racist because he masturbates to Beyoncé — but jumps across the street so he won’t have to walk past a group of black people. He looks at the black guy in his office with a raised eyebrow every time he misplaces his own wallet. Both of these guys are different from but just as dangerous as the Proud Racist racist (think: the Confederate flag made into a t-shirt guy shaking his ass a Donald Trump rally).

I see these guys all the time. They start race conversations and then ask questions that they don’t really want the answers to, or they already have the answers and want to waste your time. No statistic or study or hard evidence can shift their stance; they are knee-deep in tradition and strangled by their own perspective. I’m not against anyone who wants to spend their time enlightening people who aren’t intellectually curious, but just consider that it’s hard making racists acknowledge their own racism in a system where racism is okay.

D. WATKINS - salon

W.E.B. Du Bois - "Black Reconstruction in America":

It must be remembered that the white group of laborers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage. They were given public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white. They were admitted freely with all classes of white people to public functions, public parks, and the best schools. The police were drawn from their ranks, and the courts, dependent on their votes, treated them with such leniency as to encourage lawlessness. Their vote selected public officials, and while this had small effect upon the economic situation, it had great effect upon their personal treatment and the deference shown them. White schoolhouses were the best in the community, and conspicuously placed, and they cost anywhere from twice to ten times as much per capita as the colored schools. The newspapers specialized on news that flattered the poor whites and almost utterly ignored the Negro except in crime and ridicule.

------

HISTORIAN TIMOTHY SNYDER WARNED IN A RECENT ESSAY IN THE NEW YORK TIMES:

DEMOCRACY REQUIRES INDIVIDUAL RESPONSIBILITY, WHICH IS IMPOSSIBLE WITHOUT CRITICAL HISTORY. IT THRIVES IN A SPIRIT OF SELF-AWARENESS AND SELF-CORRECTION. AUTHORITARIANISM, ON THE OTHER HAND, IS INFANTILIZING: WE SHOULD NOT HAVE TO FEEL ANY NEGATIVE EMOTIONS; DIFFICULT SUBJECTS SHOULD BE KEPT FROM US. OUR MEMORY LAWS AMOUNT TO THERAPY, A TALKING CURE. IN THE LAWS' PORTRAYAL OF THE WORLD, THE WORDS OF WHITE PEOPLE HAVE THE MAGIC POWER TO DISSOLVE THE HISTORICAL CONSEQUENCES OF SLAVERY, LYNCHINGS AND VOTER SUPPRESSION. RACISM IS OVER WHEN WHITE PEOPLE SAY SO.

WE START BY SAYING WE ARE NOT RACISTS. YES, THAT FELT NICE. AND NOW WE SHOULD MAKE SURE THAT NO ONE SAYS ANYTHING THAT MIGHT UPSET US. THE FIGHT AGAINST RACISM BECOMES THE SEARCH FOR A LANGUAGE THAT MAKES WHITE PEOPLE FEEL GOOD. THE LAWS THEMSELVES MODEL THE DESIRED RHETORIC. WE ARE JUST TRYING TO BE FAIR. WE BEHAVE NEUTRALLY. WE ARE INNOCENT.

articles of interest

*SLAVERY ISN’T JUST BLACK HISTORY — IT’S US HISTORY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*RACIAL INEQUITY LEADS TO LOST BUSINESS AND INVESTMENT

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*White women benefit most from affirmative action — and are among its fiercest opponents(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ACTUALLY, IT’S NOT “OK TO BE WHITE”

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*White men refusing to share power is a silver stake piercing the heart of American democracy(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE RACIST HISTORY OF ABORTION AND MIDWIFERY BANS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Qualified immunity is rooted in white supremacy and gives cops a free pass to lynch Black people(ARTICLE BELOW)

*‘Conscious and Deliberate’: Black Workers Say Mississippi Farm Imported White South Africans to Replace Them at Higher Wages for the Same Work

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*54 PERCENT OF BLACK AMERICANS SAY THEY HAVE EXPERIENCED UNFAIR TREATMENT: GALLUP

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Texas Physician Makes History as 9th Black Female Pediatric Surgeon In the U.S., Recalls Being Asked If She Was There to Change the Sheets During Residency

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*While Democrats Work on Infrastructure, Republicans Are Busy Defending Slavery

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*FACEBOOK TOLD BLACK APPLICANT WITH PH.D. SHE NEEDED TO SHOW SHE WAS A “CULTURE FIT”

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*BLACK HISTORY MONTH MEANS GRAPPLING WITH THE FULL LEGACY OF RACISM IN THE US

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Trump's regime defends racism

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*MCDONALD'S DISCRIMINATES AGAINST BLACK FRANCHISEES, LAWSUIT CLAIMS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Study Finds Black Newborns Have Higher Mortality Rates Under Care of White Doctors Than with Black Physicians(ARTICLE BELOW)

*African Americans have long defied white supremacy and celebrated Black culture in public spaces(ARTICLE BELOW)

*RITE AID DEPLOYED FACIAL RECOGNITION SYSTEMS IN HUNDREDS OF U.S. STORES

(ARTICLE BELOW)

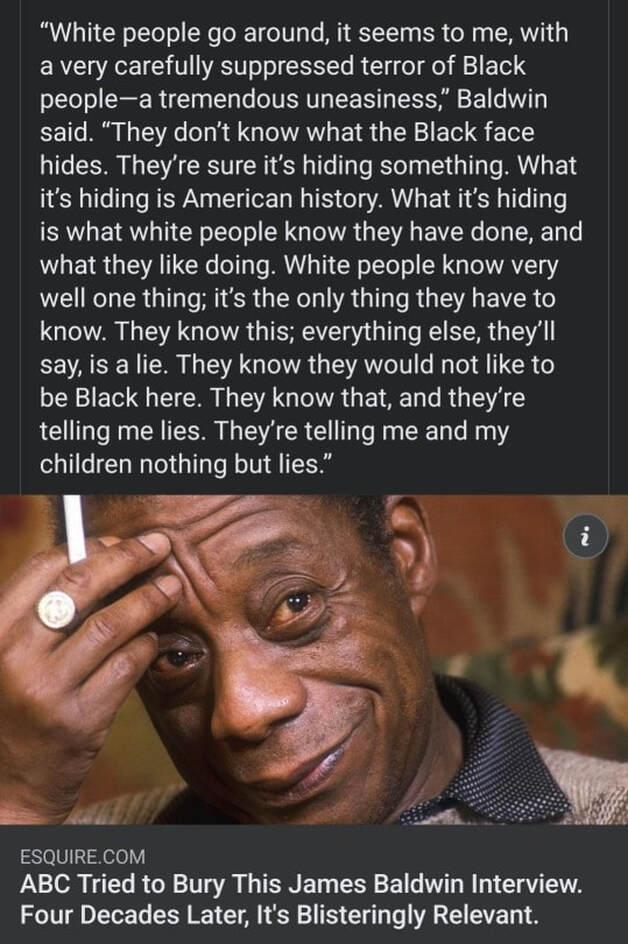

*A Letter to My Nephew by james baldwin

(excerpt below)

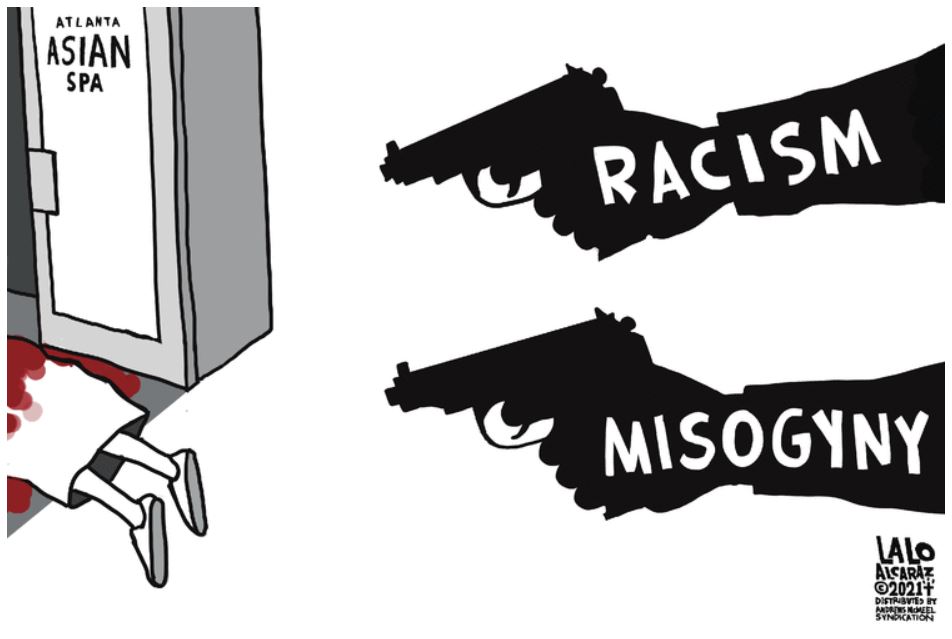

*ASIAN AND BLACK AMERICANS REPORT HEIGHTENED DISCRIMINATION AMID CORONAVIRUS OUTBREAK, POLL FINDS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE FBI HAS A HISTORY OF TARGETING BLACK ACTIVISTS. THAT'S STILL TRUE TODAY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Redlining Is Still Creating Racial Disparities 50 Years After It Was Banned

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A Giant Plastics Company Tried to Halt a Juneteenth Ceremony for Buried Slaves

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*US University Leading COVID Response Leaves Black Workers Behind

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*He Didn’t File Charges in the Arbery Case. But He Spent Years Accusing a Black Grandma of Voter Fraud.(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The US’s Failed Response to the Pandemic Is Rooted in Anti-Blackness

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*BEING A PERSON OF COLOR ISN’T A RISK FACTOR FOR CORONAVIRUS. LIVING IN A RACIST COUNTRY IS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Environmental Racism Is Killing Black Communities In Louisiana

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Skin Color Discrimination: The Latino Case

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Landmark US case to expose rampant racial bias behind the death penalty

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*'Dying of whiteness': why racism is at the heart of America's gun inaction

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The US Gave Slavers Their Land Back. What About Black Folks’ Reparations?

(EXCERPT BELOW)

*THE RADICALIZATION OF WHITE AMERICA: HOW DONALD TRUMP WEAPONIZED WHITENESS

(EXCERPT BELOW)

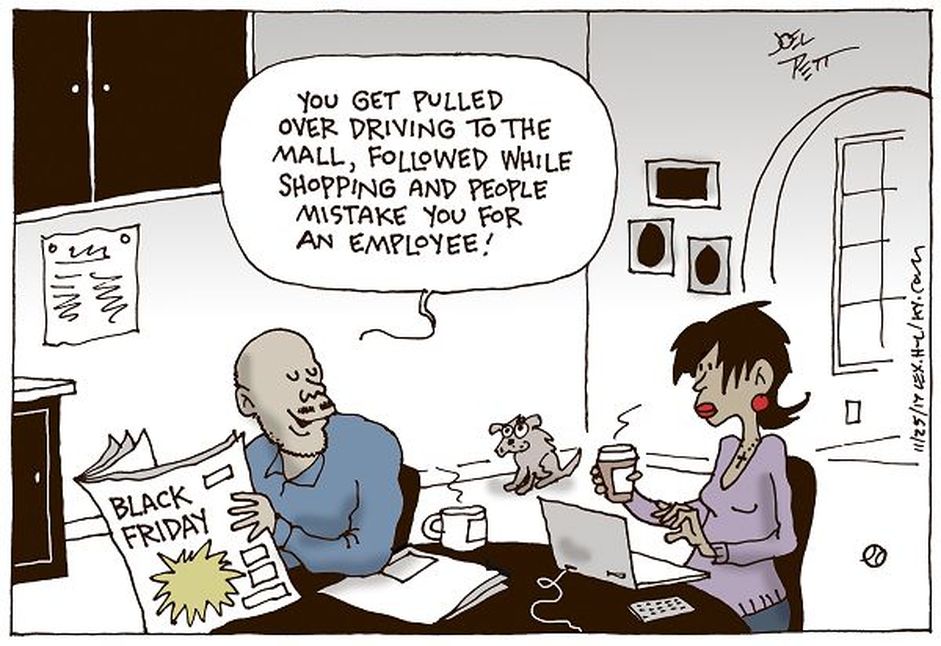

*Living while Black

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Coard: Non-voting Blacks get no thanks, deserve no benefits

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*#NotRacists Be Like: The Top 10 Phrases Used by People Who Claim They Are Not Racist

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Coard: Non-voting Blacks commit suicidal lynchings

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*White People Explain Why They Feel Oppressed

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*These 2 psychologists are dismantling the myth of white intellectual superiority

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Five Big Myths Debunked by the New York Times Report On Race, Economic, and Gender Inequality

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*What’s wrong with white teachers?

Closing the performance gap between black and white teachers means talking about racism(article below)

*THE BLACK AMERICAN EXPERIENCE(ARTICLE BELOW)

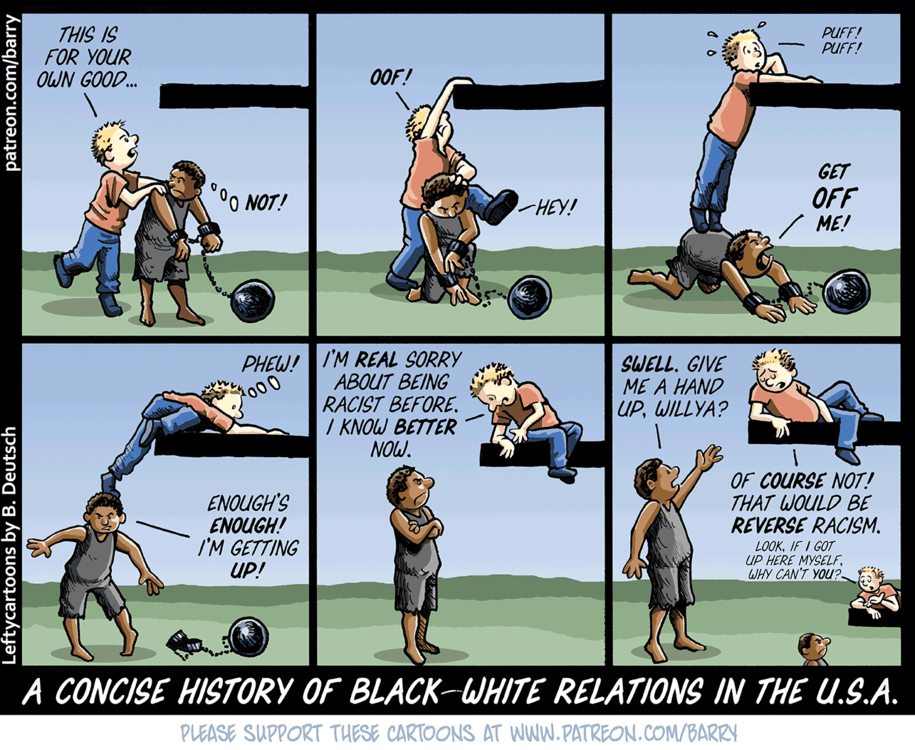

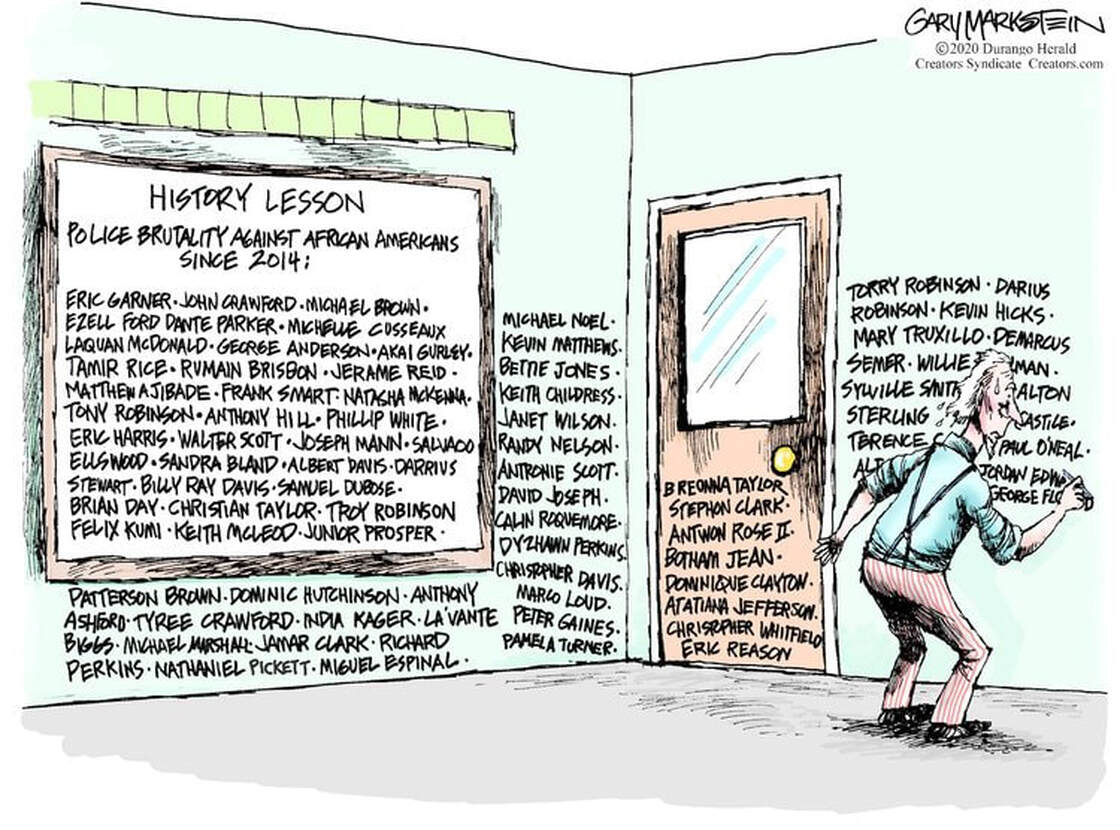

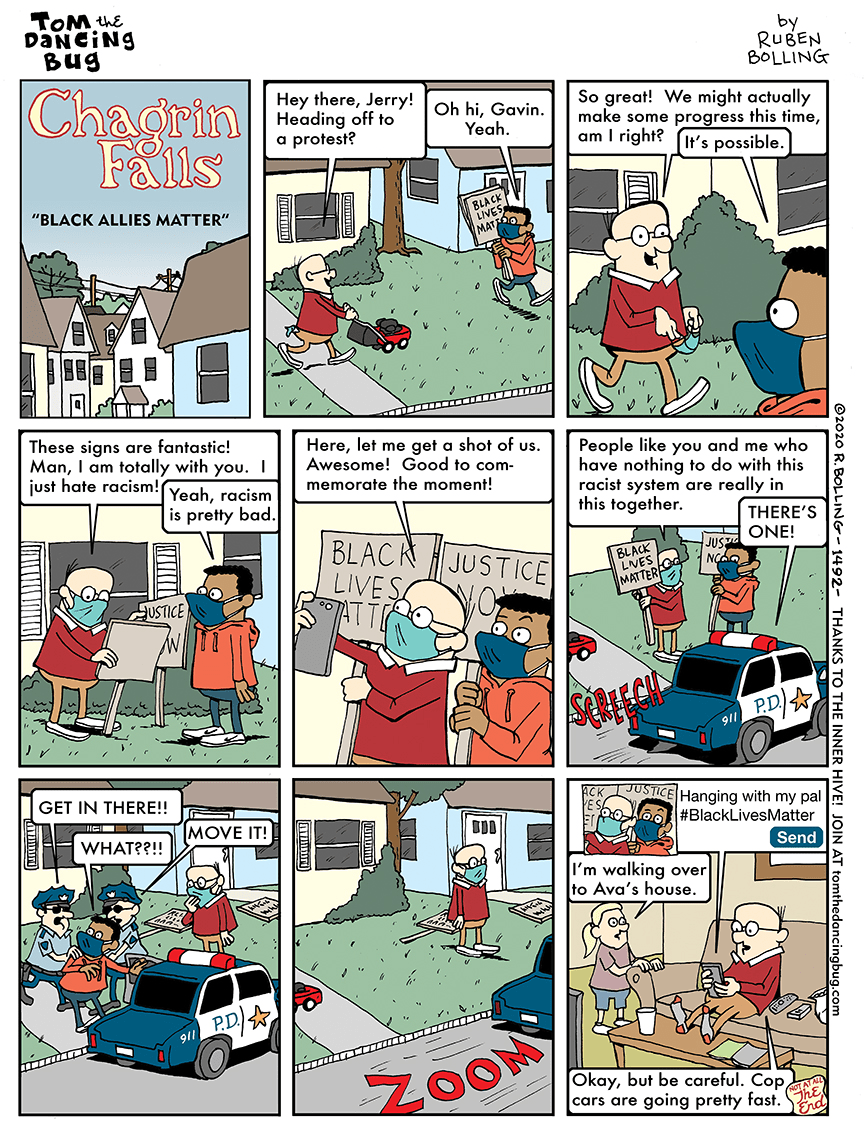

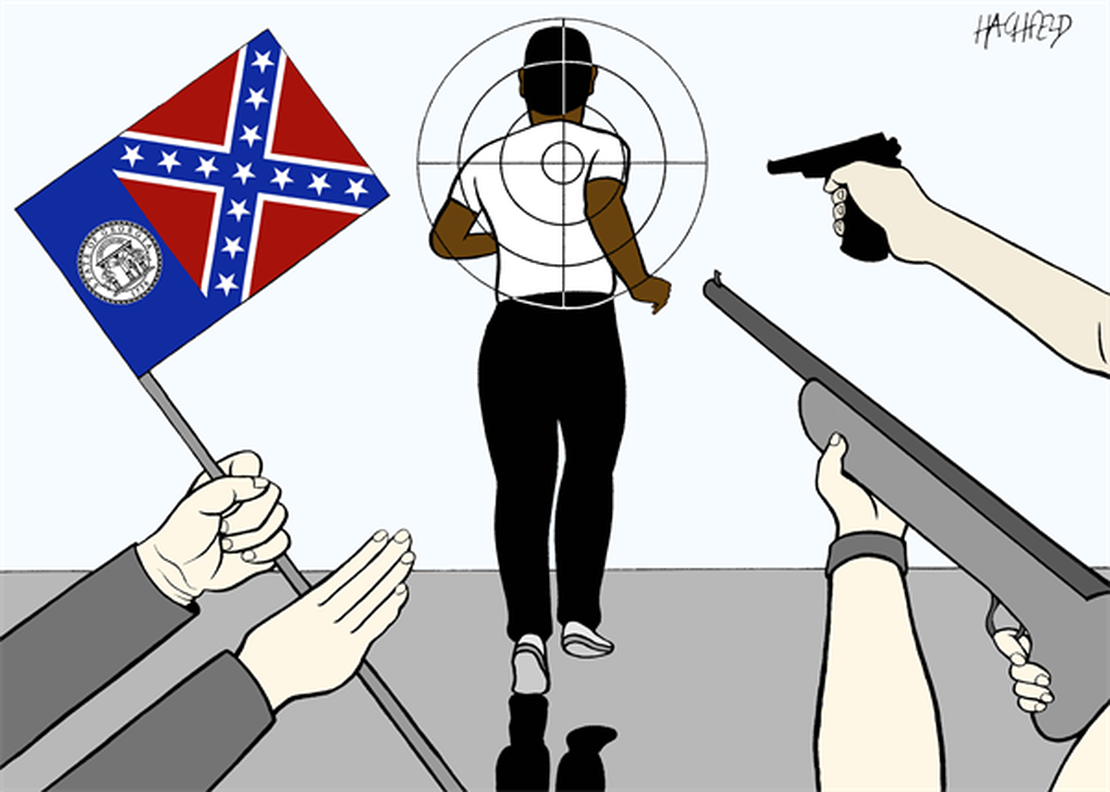

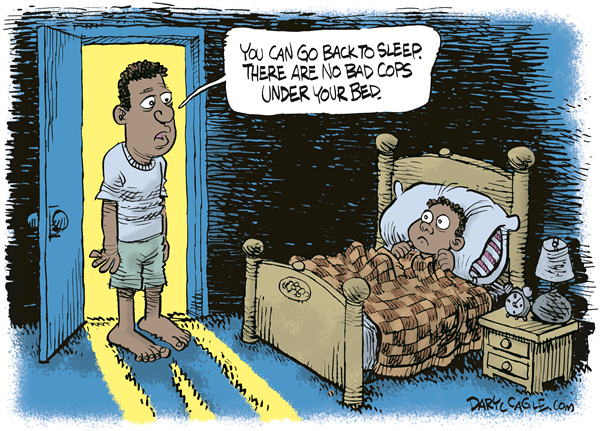

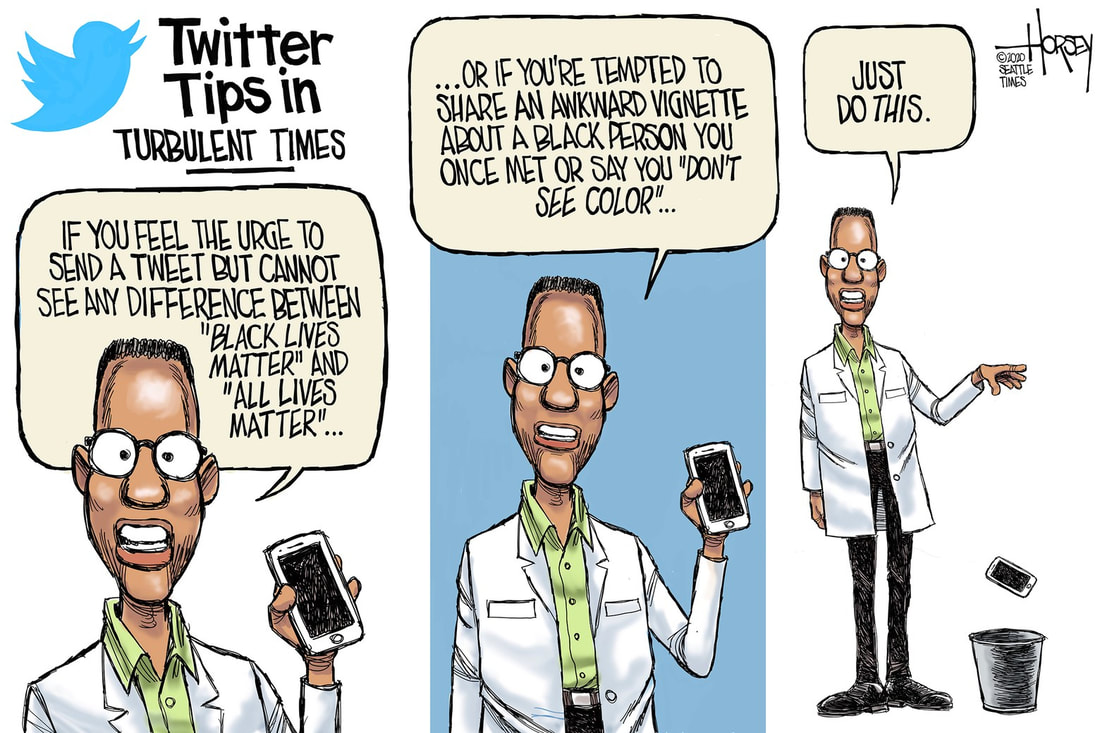

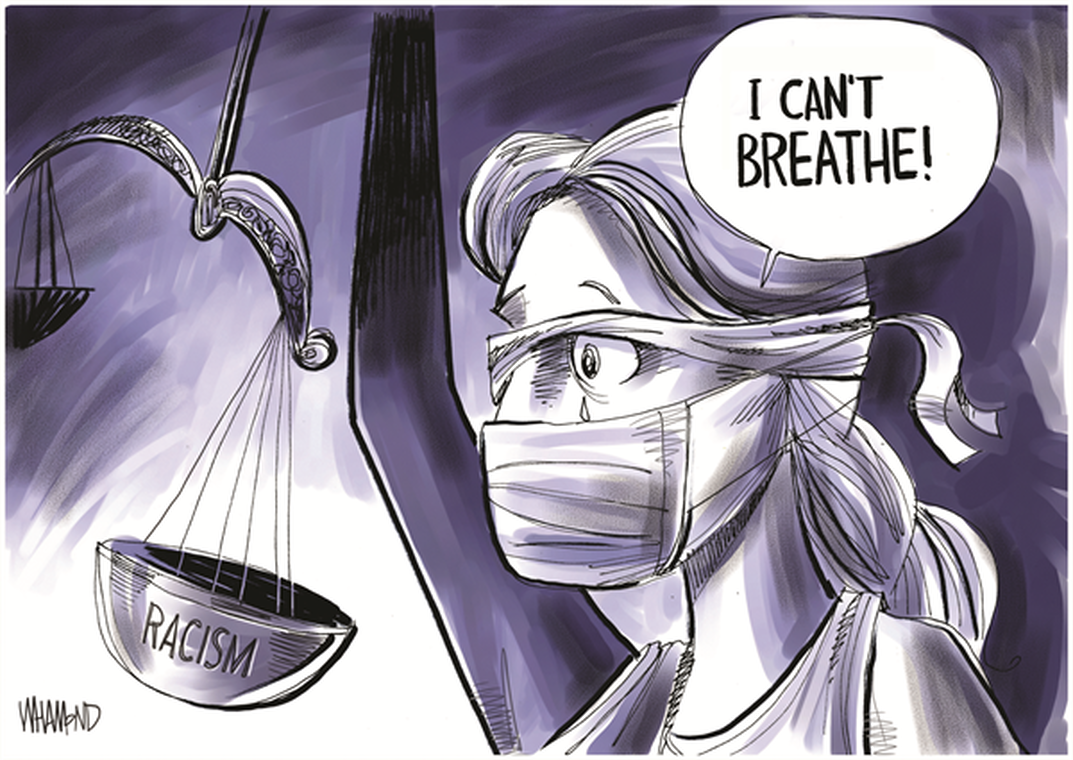

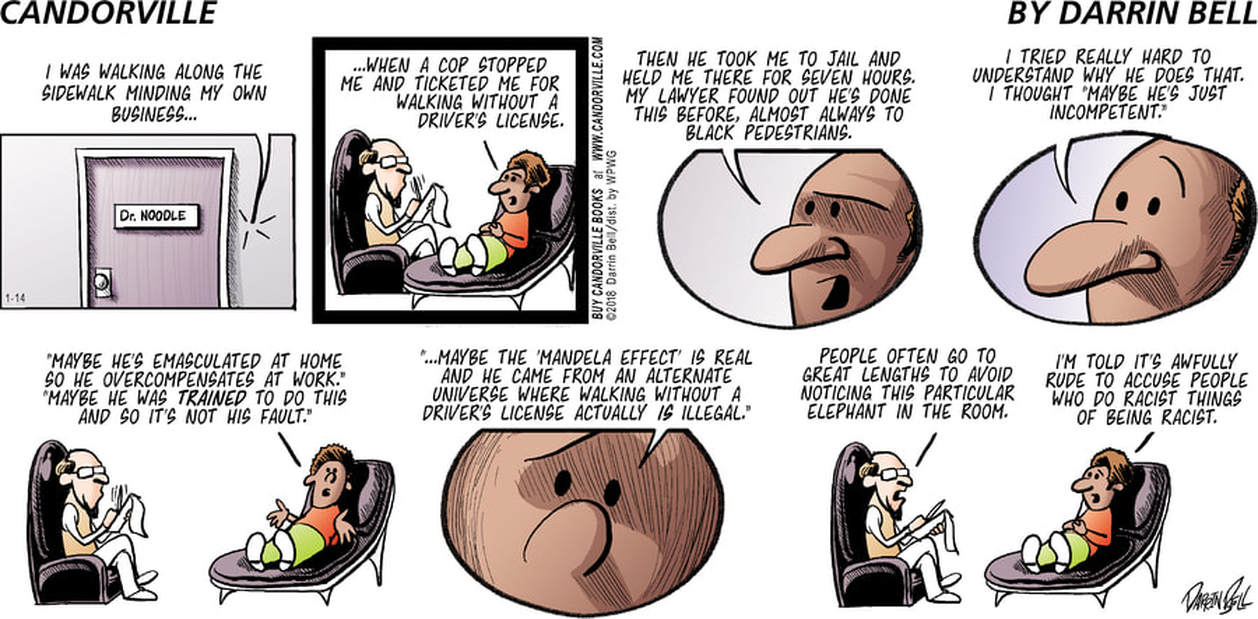

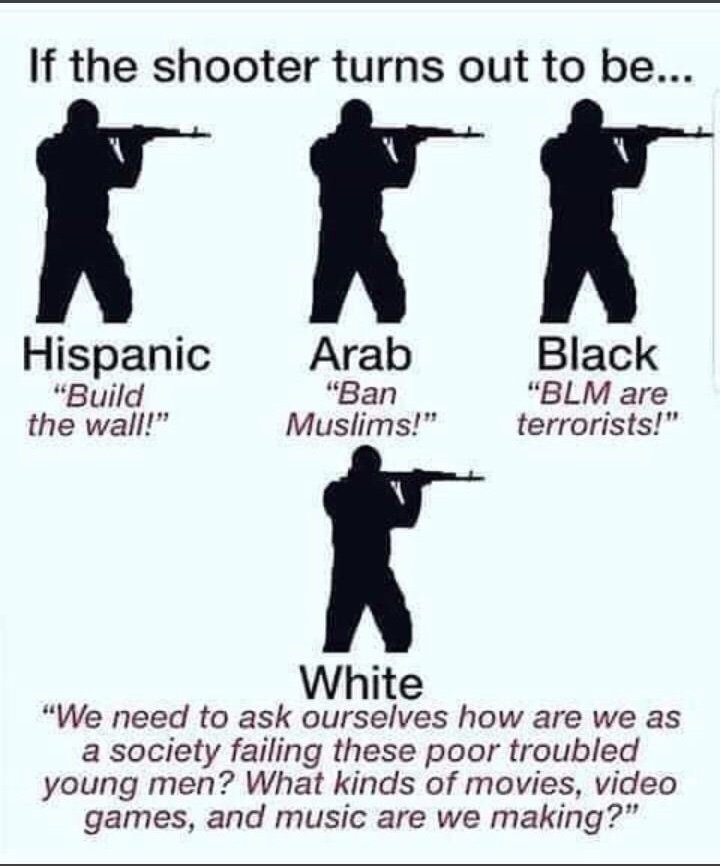

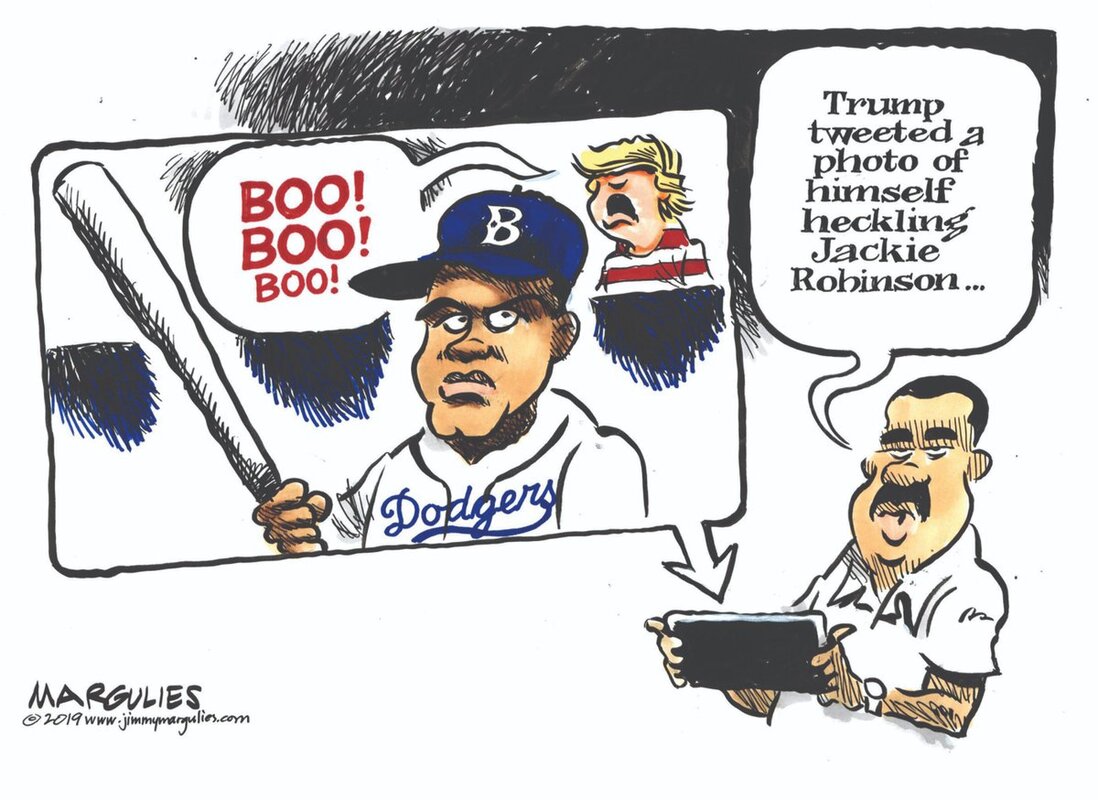

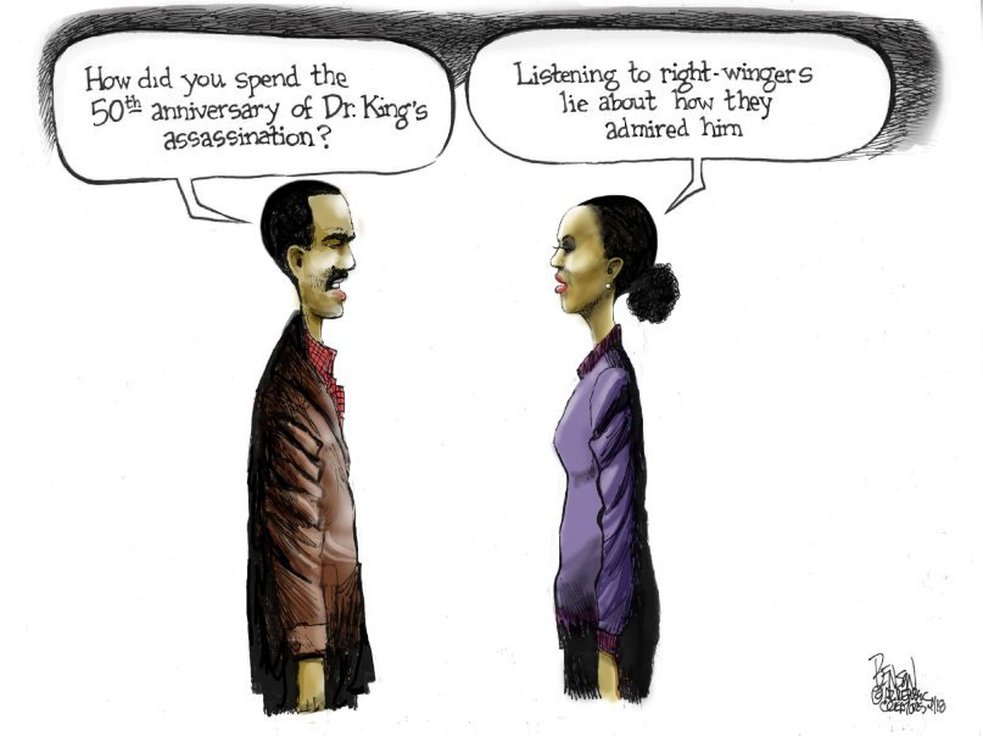

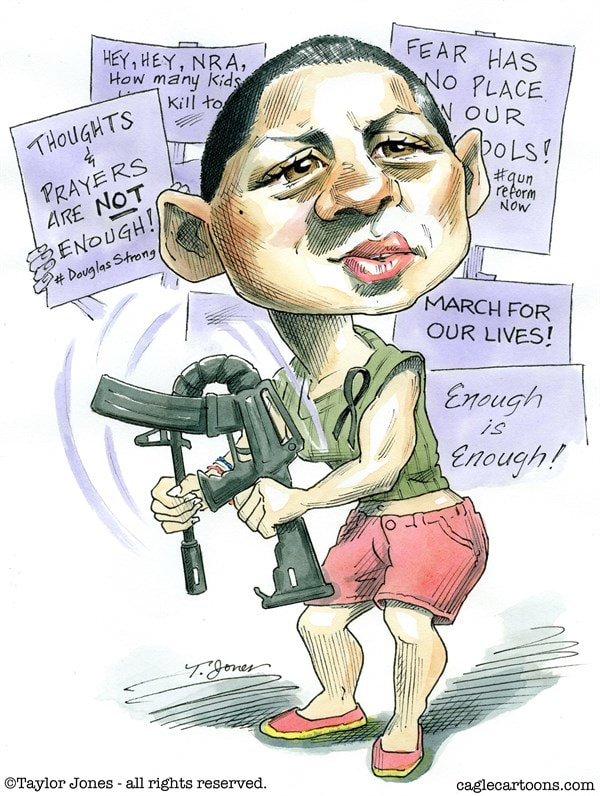

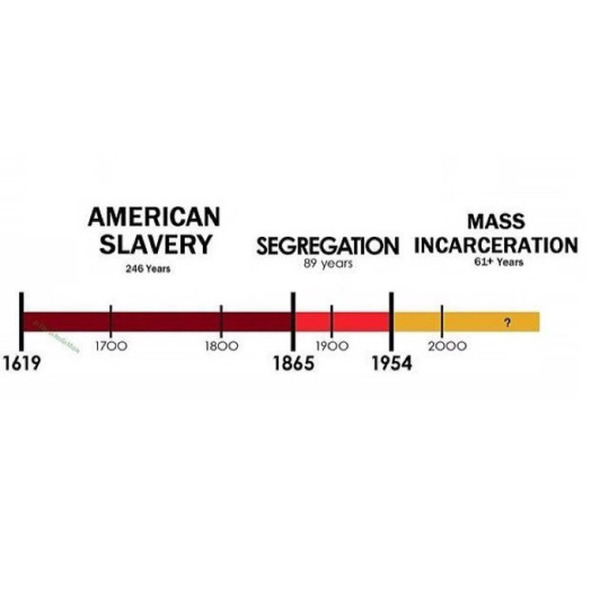

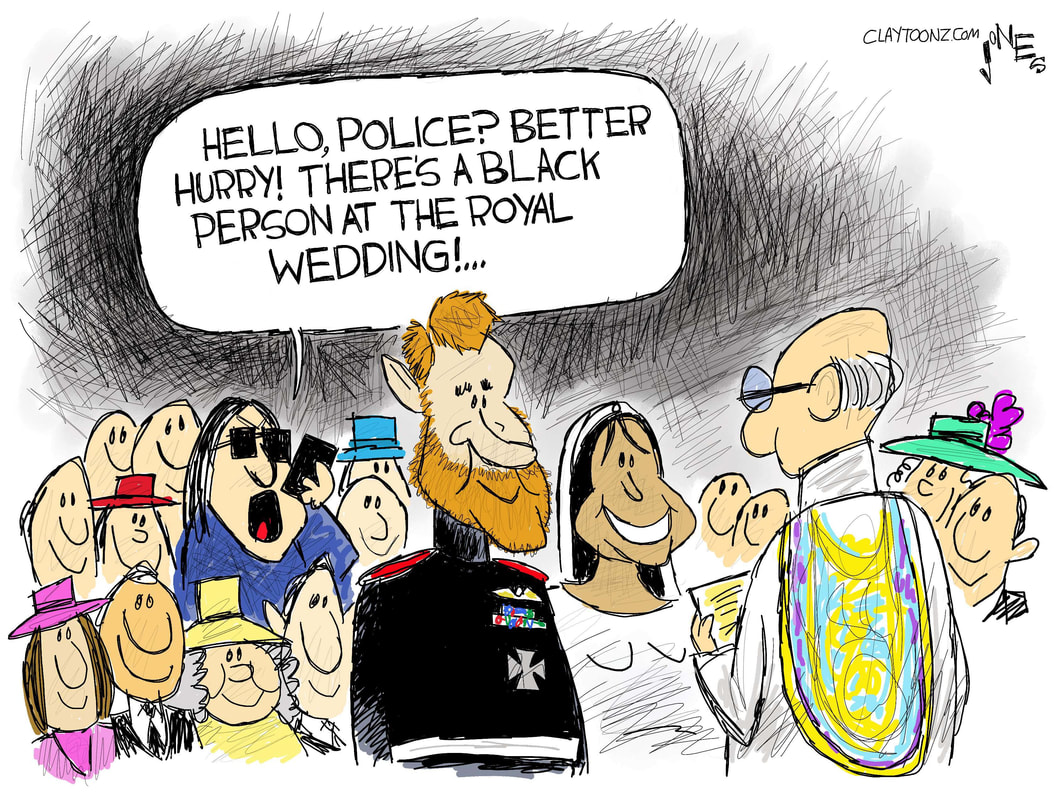

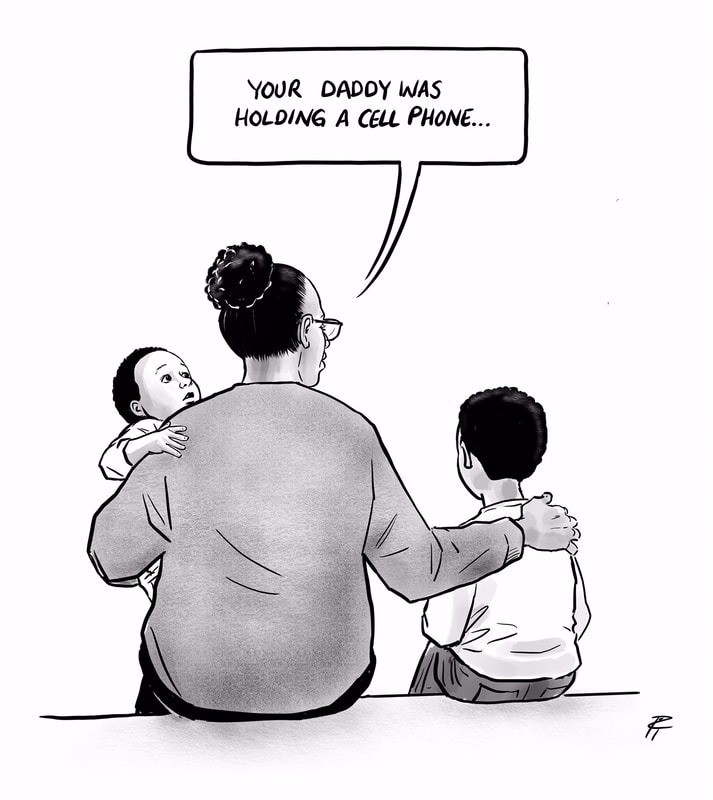

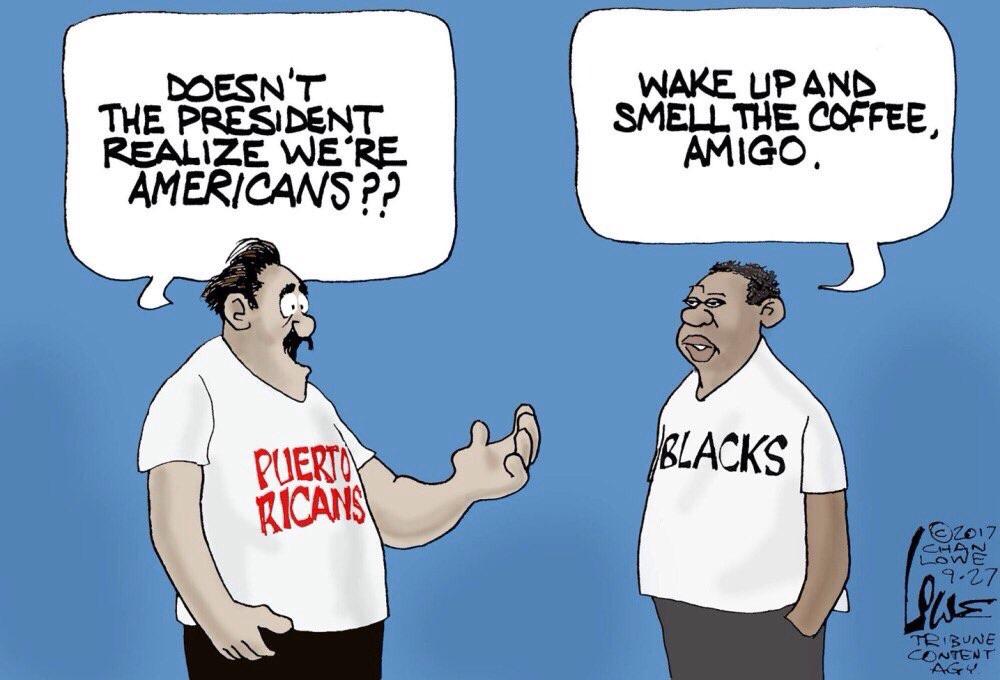

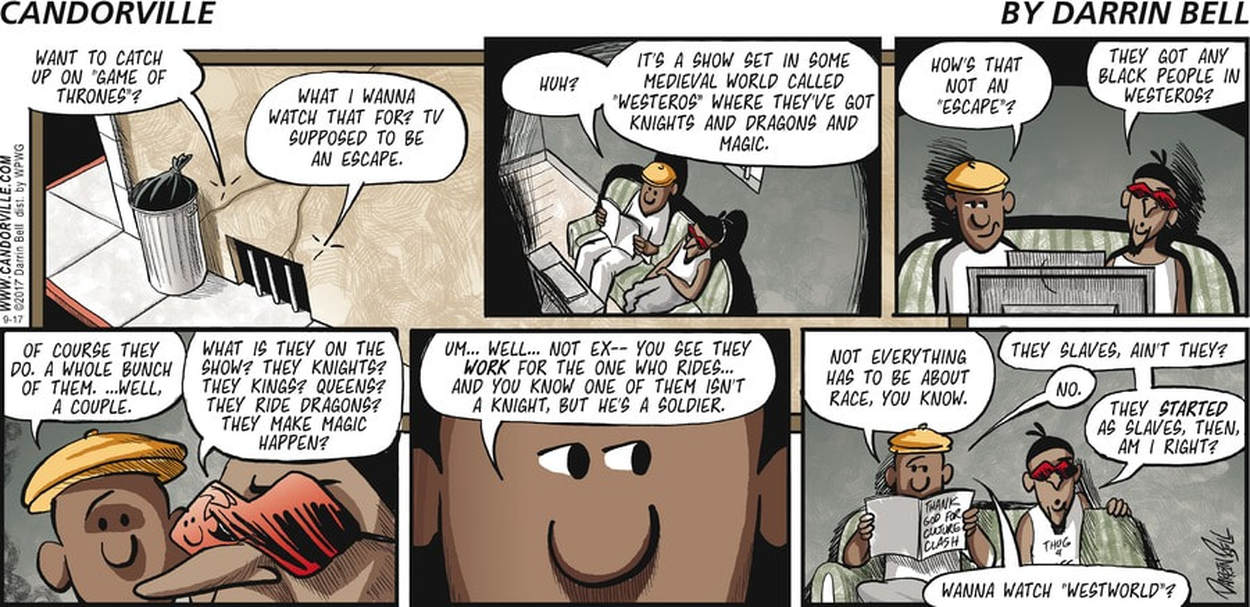

*cartoons(below)

Slavery Isn’t Just Black History — It’s US History

Over 100 political leaders descend from enslavers. It’s time for the U.S. to confront this history and its impacts.

By Kwolanne Felix , TRUTHOUT

Published July 17, 2023

A recent Reuters investigation reveals that more than 100 U.S. political leaders descend from slaveholders. This includes five living U.S. presidents, two Supreme Court justices, 11 governors and 100 legislators across party lines. Amid rising debates on slavery and its legacy, from school curricula to the movement for reparations, Reuters examined how politicians are reckoning with these discussions as they reflect on their own familial ties to slavery, but many refused to comment on the findings. This examination refutes the notion that slavery is a relic of the distant past that has no bearing on our current society. It serves as a firm reminder of the legacies of slavery in the U.S. and how it shapes our political landscape.

Slavery was an economic and social system that allowed families to reproduce wealth, status and power. It was simultaneously a systemic issue and an individual choice: Slavery underpinned the economies of Europe, West Africa, and North and South America; and it was upheld by individual choices to buy and sell enslaved people.

As the descendants of enslavers, these 100+ political elite are direct recipients of the wealth and resources created by slavery. Slavery would shape all parts of the U.S. economy, from agriculture, textiles, banks, insurance and transportation. The 4 million enslaved people alive in the 1860s generated an estimated $3.5 billion, making them the single largest “financial asset” in the U.S. economy at the time. It is no understatement that the U.S. is built on the wealth of slavery.

For many African Americans, the link between slavery and their history is obvious and irrefutable. Those who descend from Africans brought to the U.S. through the transatlantic slave trade have no choice but to be aware of this truth. Even though I am not African American, I am the descendant of enslaved people relocated to the Caribbean, and there is no way for me to address my history without discussing slavery. It transformed the lives, cultures, languages and identities of my ancestors.

Even though initial feelings of guilt and shame can arise when reflecting on slavery and its legacies, addressing this history can serve as an important step in seeking racial justice. I decided to study the history of the African Diaspora for this reason during college. Learning about slavery and its impacts gives me a better understanding of the American socio-political landscape. I learned that there is no running from our history; it has already found a way to catch up with us in the present. It’s understandable that conversations around slavery are uncomfortable — it was a horrible system of mass human trafficking that displaced millions of people and reduced them to property. Even during slavery, Americans struggled with addressing the brutality of the system, so much so that it led to Civil War. It’s no surprise that today it’s still a sore topic. But that discomfort shouldn’t produce apathy, but instead could be a platform to further reflection.

Unfortunately, right-wing movements to actively erase this vital history are growing across the country. The rhetoric that discussing slavery makes white students feel bad is used to justify this erasure. In Florida, for instance, Gov. Ron Desantis has pushed laws that ban discussing the truth about U.S. slavery in schools, and has gutted AP African American history courses of their content on slavery and civil rights movements. As a Floridian, I’m frustrated knowing that the projects I put on for Black History Month just five years ago, that ignited my love for history, are now illegal in my school. The history of slavery isn’t just African American history – it is U.S. history, and all students need to learn it.

When discussing the legacies of slavery, the goal isn’t necessarily to assign blame. There are no historical slaveholders that are alive now, and their descendants aren’t responsible for this horrific system. However, that doesn’t negate the need to reflect on how this past system continues to shape the country to the detriment of some and the benefit of others. Slavery reinforced systems of racial hierarchy that still exist in the U.S. today. Black Americans, even those not descendants of American enslaved people, still pay the price of this inequality. White Americans also don’t need to directly descend from slaveholders to benefit from the legacy of this inequality either.

Slavery is an uncomfortable topic for most Americans. For some Americans, it evokes ancestral pain and dehumanization, but also resilience and survival. For others, it brings up feelings of shame and confusing questions of responsibility.

Movements demanding reparations are striking a chord with many Americans, leading to contentious discussions. On the local, state and federal levels, there have been efforts to research and propose reparation efforts to address racial injustice, particularly for African Americans. These demands have been met with mixed responses, as some efforts are successful and others are unsuccessful. Uncertainty looms on how to properly address slavery and the legacy of racial injustice — and move forward.

U.S. history is incomplete without reflecting on slavery and its effects, and when we address this history properly, we gain a better understanding of the country’s present and future. When we understand slavery, we can understand present economic conditions across different communities, geographic distributions, the rise of major cities, labor patterns across the country, and the emergence of diverse American cultures, cuisines and traditions.

We have so much more to gain from learning our history when we let go of our fears.

Slavery was an economic and social system that allowed families to reproduce wealth, status and power. It was simultaneously a systemic issue and an individual choice: Slavery underpinned the economies of Europe, West Africa, and North and South America; and it was upheld by individual choices to buy and sell enslaved people.

As the descendants of enslavers, these 100+ political elite are direct recipients of the wealth and resources created by slavery. Slavery would shape all parts of the U.S. economy, from agriculture, textiles, banks, insurance and transportation. The 4 million enslaved people alive in the 1860s generated an estimated $3.5 billion, making them the single largest “financial asset” in the U.S. economy at the time. It is no understatement that the U.S. is built on the wealth of slavery.

For many African Americans, the link between slavery and their history is obvious and irrefutable. Those who descend from Africans brought to the U.S. through the transatlantic slave trade have no choice but to be aware of this truth. Even though I am not African American, I am the descendant of enslaved people relocated to the Caribbean, and there is no way for me to address my history without discussing slavery. It transformed the lives, cultures, languages and identities of my ancestors.

Even though initial feelings of guilt and shame can arise when reflecting on slavery and its legacies, addressing this history can serve as an important step in seeking racial justice. I decided to study the history of the African Diaspora for this reason during college. Learning about slavery and its impacts gives me a better understanding of the American socio-political landscape. I learned that there is no running from our history; it has already found a way to catch up with us in the present. It’s understandable that conversations around slavery are uncomfortable — it was a horrible system of mass human trafficking that displaced millions of people and reduced them to property. Even during slavery, Americans struggled with addressing the brutality of the system, so much so that it led to Civil War. It’s no surprise that today it’s still a sore topic. But that discomfort shouldn’t produce apathy, but instead could be a platform to further reflection.

Unfortunately, right-wing movements to actively erase this vital history are growing across the country. The rhetoric that discussing slavery makes white students feel bad is used to justify this erasure. In Florida, for instance, Gov. Ron Desantis has pushed laws that ban discussing the truth about U.S. slavery in schools, and has gutted AP African American history courses of their content on slavery and civil rights movements. As a Floridian, I’m frustrated knowing that the projects I put on for Black History Month just five years ago, that ignited my love for history, are now illegal in my school. The history of slavery isn’t just African American history – it is U.S. history, and all students need to learn it.

When discussing the legacies of slavery, the goal isn’t necessarily to assign blame. There are no historical slaveholders that are alive now, and their descendants aren’t responsible for this horrific system. However, that doesn’t negate the need to reflect on how this past system continues to shape the country to the detriment of some and the benefit of others. Slavery reinforced systems of racial hierarchy that still exist in the U.S. today. Black Americans, even those not descendants of American enslaved people, still pay the price of this inequality. White Americans also don’t need to directly descend from slaveholders to benefit from the legacy of this inequality either.

Slavery is an uncomfortable topic for most Americans. For some Americans, it evokes ancestral pain and dehumanization, but also resilience and survival. For others, it brings up feelings of shame and confusing questions of responsibility.

Movements demanding reparations are striking a chord with many Americans, leading to contentious discussions. On the local, state and federal levels, there have been efforts to research and propose reparation efforts to address racial injustice, particularly for African Americans. These demands have been met with mixed responses, as some efforts are successful and others are unsuccessful. Uncertainty looms on how to properly address slavery and the legacy of racial injustice — and move forward.

U.S. history is incomplete without reflecting on slavery and its effects, and when we address this history properly, we gain a better understanding of the country’s present and future. When we understand slavery, we can understand present economic conditions across different communities, geographic distributions, the rise of major cities, labor patterns across the country, and the emergence of diverse American cultures, cuisines and traditions.

We have so much more to gain from learning our history when we let go of our fears.

cost of racism!!

Racial Inequity Leads To Lost Business and Investment

barron's

7/4/2023

Racial inequity is a significant drag on the U.S. economy, although one that isn’t mentioned in routine assessments of GDP and quarterly earnings.

The good news is that correcting these inequities at U.S. corporations and financial institutions could boost consumption and investment in the U.S. alone “by hundreds of billions of dollars by 2050,” according to a research brief published late last month from the Investment Integration Project, or TIIP.

“The U.S. cannot reach its full economic and growth potential, and effectively compete in the global economy, if it continues to exclude people of color from fully participating in its economy,” the report said.

There’s the simple fact that people of color—including Black, indigenous, Pacific Islanders, Latino, East and South Asian, and Arab and Middle Eastern people—will comprise 52% of the nation’s population by 2050.

Not giving people in more than half of the country the same access to income and wealth leads to social destabilization, which, in turn, “increases market volatility and uncertainty and creates a general sense of economic instability, impacting investment opportunities across all asset classes,” the report said.

Making sure racial equity exists at U.S. corporations and financial institutions can ensure the U.S. doesn’t continue on this path, says William Burckart, CEO of TIIP, a Massachusetts-based investment consulting and applied research firm focused on how investing strategies can drive systemic change.

It starts with “making sure that your workforce, including your leadership,

reflects the diversity of the country, the demographics of the country,

which currently right now, it does not,” Burckart says.

The report, “Introduction to Racial Inequity as a Systemic Risk,” was put together by a working group of impact-investment professionals and received funding from the New York-based Surdna Foundation. It describes “how investors can leverage conventional investment techniques and more advanced approaches to manage the risks of racial inequity and embed racial equity across portfolios,” Burckart says.

Investing to Correct Inequity

Currently, 22.2% of board seats at Fortune 500 companies are held by Blacks, Asians, Pacific Islanders, and people from Hispanic or Latino backgrounds, according to a recent report from Deloitte. White men, meanwhile, manage nearly 98% of financial assets in the U.S., according to the TIIP report.

“You can say a lot of things about wanting to invest with [diversity, equity, and inclusion] considerations, but when the actual folks that are making the decisions do not represent the diversity of communities that comprise the U.S. economy, that’s a problem,” Burckart says.

“It’s not just a problem from a moral perspective,” he says. “It’s a disconnect that’s resulting in investors missing potential upside, but then also creating a kind of tail of inequity that is ultimately going to create more unstable returns in the future.”

One action asset owners—such as foundations, family offices, and pension funds—can take is to remove barriers such as requiring investment managers to have long track records or large amounts of assets under management that prohibit them from investing in emerging firms led by more racially diverse teams.

That often begins by hiring more diverse leadership teams who can relate to and spot value in emerging managers that don’t have conventional histories, Burckart says.

Security selection and portfolio construction are other levers investors can use. For instance, “make sure the companies that you’re investing in have leadership that is diverse and/or that you can see the pathway for getting them to be more diverse,” he says.

Investors also have to make sure portfolio managers who say they view racial inequity as a risk, are actually doing something about it.

Strengthening racial equity considerations should also be incorporated within a financial institution’s or asset owner’s statement of investment beliefs. A statement can allow trustees, particularly of bigger financial institutions, to reflect on how they allocate capital in markets and address their fiduciary duty. “Enshrining this in governing policies is important,” Burckart says.

System-Level Change

Investors can also go beyond corporate governance and portfolio decision making to work with peers, set new industry standards, and exercise political influence to create what TIIP has defined as system-level change, according to the report.

The idea is investors can operate more intentionally, and collectively, to “enhance the way they invest but also the way others invest,” Burckart says. “They ultimately have to create new kinds of investment opportunities that fundamentally address racial inequity as part of their thesis and take the jargon away from it.”

The St. Paul & Minnesota Foundation, for instance, devised due diligence criteria for managers that included racial justice considerations. It took its recommendations to the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment investor network to broaden the reach of these standards.

After the Rio de Janeiro-based Vale’s mining disaster at the Brumadinho dam in 2019 that killed 270 people in Brazil, a group of investors got together to demand improved mining safety standards not just for Vale, but for the entire industry, Burckart says.

Investors could similarly collaborate to create standards and a database cataloging the racial composition of both public and private companies, he says.

System-level change also can come from impact investing firms that take a broader look at their mandates. The objective of a sustainable water fund, for instance, shouldn’t just be profiting off of the privatization of water around the world, but addressing issues of water scarcity and water quality.

“They ultimately need to start to pursue investments that promote business models that help to resolve racial inequity, not just profit from it,” Burckart says.

The good news is that correcting these inequities at U.S. corporations and financial institutions could boost consumption and investment in the U.S. alone “by hundreds of billions of dollars by 2050,” according to a research brief published late last month from the Investment Integration Project, or TIIP.

“The U.S. cannot reach its full economic and growth potential, and effectively compete in the global economy, if it continues to exclude people of color from fully participating in its economy,” the report said.

There’s the simple fact that people of color—including Black, indigenous, Pacific Islanders, Latino, East and South Asian, and Arab and Middle Eastern people—will comprise 52% of the nation’s population by 2050.

Not giving people in more than half of the country the same access to income and wealth leads to social destabilization, which, in turn, “increases market volatility and uncertainty and creates a general sense of economic instability, impacting investment opportunities across all asset classes,” the report said.

Making sure racial equity exists at U.S. corporations and financial institutions can ensure the U.S. doesn’t continue on this path, says William Burckart, CEO of TIIP, a Massachusetts-based investment consulting and applied research firm focused on how investing strategies can drive systemic change.

It starts with “making sure that your workforce, including your leadership,

reflects the diversity of the country, the demographics of the country,

which currently right now, it does not,” Burckart says.

The report, “Introduction to Racial Inequity as a Systemic Risk,” was put together by a working group of impact-investment professionals and received funding from the New York-based Surdna Foundation. It describes “how investors can leverage conventional investment techniques and more advanced approaches to manage the risks of racial inequity and embed racial equity across portfolios,” Burckart says.

Investing to Correct Inequity

Currently, 22.2% of board seats at Fortune 500 companies are held by Blacks, Asians, Pacific Islanders, and people from Hispanic or Latino backgrounds, according to a recent report from Deloitte. White men, meanwhile, manage nearly 98% of financial assets in the U.S., according to the TIIP report.

“You can say a lot of things about wanting to invest with [diversity, equity, and inclusion] considerations, but when the actual folks that are making the decisions do not represent the diversity of communities that comprise the U.S. economy, that’s a problem,” Burckart says.

“It’s not just a problem from a moral perspective,” he says. “It’s a disconnect that’s resulting in investors missing potential upside, but then also creating a kind of tail of inequity that is ultimately going to create more unstable returns in the future.”

One action asset owners—such as foundations, family offices, and pension funds—can take is to remove barriers such as requiring investment managers to have long track records or large amounts of assets under management that prohibit them from investing in emerging firms led by more racially diverse teams.

That often begins by hiring more diverse leadership teams who can relate to and spot value in emerging managers that don’t have conventional histories, Burckart says.

Security selection and portfolio construction are other levers investors can use. For instance, “make sure the companies that you’re investing in have leadership that is diverse and/or that you can see the pathway for getting them to be more diverse,” he says.

Investors also have to make sure portfolio managers who say they view racial inequity as a risk, are actually doing something about it.

Strengthening racial equity considerations should also be incorporated within a financial institution’s or asset owner’s statement of investment beliefs. A statement can allow trustees, particularly of bigger financial institutions, to reflect on how they allocate capital in markets and address their fiduciary duty. “Enshrining this in governing policies is important,” Burckart says.

System-Level Change

Investors can also go beyond corporate governance and portfolio decision making to work with peers, set new industry standards, and exercise political influence to create what TIIP has defined as system-level change, according to the report.

The idea is investors can operate more intentionally, and collectively, to “enhance the way they invest but also the way others invest,” Burckart says. “They ultimately have to create new kinds of investment opportunities that fundamentally address racial inequity as part of their thesis and take the jargon away from it.”

The St. Paul & Minnesota Foundation, for instance, devised due diligence criteria for managers that included racial justice considerations. It took its recommendations to the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment investor network to broaden the reach of these standards.

After the Rio de Janeiro-based Vale’s mining disaster at the Brumadinho dam in 2019 that killed 270 people in Brazil, a group of investors got together to demand improved mining safety standards not just for Vale, but for the entire industry, Burckart says.

Investors could similarly collaborate to create standards and a database cataloging the racial composition of both public and private companies, he says.

System-level change also can come from impact investing firms that take a broader look at their mandates. The objective of a sustainable water fund, for instance, shouldn’t just be profiting off of the privatization of water around the world, but addressing issues of water scarcity and water quality.

“They ultimately need to start to pursue investments that promote business models that help to resolve racial inequity, not just profit from it,” Burckart says.

excerpt: White women benefit most from affirmative action — and are among its fiercest opponents

The willingness to erase white women from the story of affirmative action is part of the problem.

By Victoria M. Massie - vox

6/29/2023

University of Texas Case:

The University of Texas Austin was Abigail Fisher's dream school. Fisher, from Sugar Land, Texas, a wealthy Houston suburb, earned a 3.59 GPA in high school and scored an 1180 on the SATs.

Not bad, but not enough for the highly selective UT Austin in fall 2008; Fisher's dreams were dashed when she was denied admission.

In response, Fisher sued. Her argument? That applicants of color, whose racial backgrounds were included as a component of the university's holistic review process, were less-qualified students and had displaced her.

Students graduating in the top 10 percent of any Texas high school are granted an automatic spot at UT Austin. Other students are evaluated through a holistic review process including a race-blind review of essays and creating a personal achievement score based on leadership potential, honors and awards, work experience, and special circumstances that include socioeconomic considerations such as race.

A few are accepted through provisional slots that include attending a summer program prior to the fall. One black student, four Latino students, and 42 white students with lower scores than Fisher were accepted under these terms. Also rejected were 168 African-American and Latino students with better scores than Fisher.

According to court documents, even if Fisher had received a perfect personal achievement score that included race (which, in itself, oversimplifies the admissions process), she still would not have necessarily qualified under UT's admission rubric.

In fact, when she applied for the class of 2012, the admission rate for non-automatic admits was more competitive than that of Harvard University.

Nonetheless, Fisher spent the past seven years in court, and Thursday the US Supreme Court ruled 4-3 that UT's admissions policy procedures are constitutional.

But the battle to erase race from the application review process for admission comes with an interesting paradox: "The primary beneficiaries of affirmative action have been Euro-American women," wrote Columbia University law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw for the University of Michigan Law Review in 2006.

A 1995 report by the California Senate Government Organization Committee found that white women held a majority of managerial jobs (57,250) compared with African Americans (10,500), Latinos (19,000), and Asian Americans (24,600) after the first two decades of affirmative action in the private sector. In 2015, a disproportionate representation of white women business owners set off concerns that New York state would not be able to bridge a racial gap among public contractors.

A 1995 report by the Department of Labor found that 6 million women overall had advances at their job that would not have been possible without affirmative action. The percentage of women physicians tripled between 1970 and 2002, from 7.6 percent to 25.2 percent, and in 2009 women were receiving a majority of bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees, according to the American Association of University Women. To be clear, these numbers include women of all races; however, breaking down affirmative action beneficiaries by race and gender seems to be rare in reported data.

Contrary to popular belief, affirmative action isn't just black. It's white, too. But affirmative action's white female faces are rarely at the center of the conversation.

---

White women have become some of affirmative action's fiercest opponents

In general, women today are more educated and make up more of the workforce than ever before, in part because of affirmative action policies. Indeed, from the tech industry to publishing, diversity has emerged as an overwhelming increase in the presence of white women, not necessarily people of color.

Incidentally, over the years white women have become some of affirmative action's most ardent opponents.

According to the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, nearly 70 percent of the 20,694 self-identified non-Hispanic white women surveyed either somewhat or strongly opposed affirmative action.

White women have also been the primary plaintiffs in the major Supreme Court affirmative action cases, with the exception of the first — Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978 — that was brought to the courts by a white man.

Twenty-five years after Bakke found that race can be one but not the only criterion for evaluating admissions applications, four white women have filed lawsuits seeking retribution for admissions rejections based on the premise that they were denied a spot over less-deserving students of color.

The first successful case to challenge affirmative action policy was Hopwood v. Texas in 1996. Cheryl Hopwood claimed that despite excellent scores and fitting the profile of a surefire admit, the University of Texas School of Law admitted 62 people of color, only nine of whom had better LSAT and GPA scores than she did.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that diversity alone was not enough to justify racial preferences. For example, only Mexican-American and African-American students' racial backgrounds were taken into consideration at UT's law school. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case, but the decision dismantled UT's earlier racial affirmative action policy and catalyzed UT's 10 percent policy to admit the best students in a state that still suffers from de facto segregation according to UT's Supreme Court briefs for the Fisher case.

But in 2003, two other white women approached the Court in parallel cases citing a misuse of race in admissions policies. In Grutter v. Bollinger, Barbara Grutter argued that she was denied admission to the University of Michigan Law School as a direct result of the law school's consideration of race in the admissions process. In Gratz v. Bollinger, Jennifer Gratz argued similarly that she was denied acceptance to the University of Michigan's flagship university in Ann Arbor as an undergrad because of race.

The Supreme Court decisions were split between the two cases. In Gratz, the justices ruled that race was being valued in ways that violated the Constitution's Equal Protection Clause — students received 20 points if they were from an underrepresented racial group compared with 5 points for artistic achievement. However, the justices ruled in Grutter that there was nothing unconstitutional about the way race was included in the law school's holistic admissions policy.

The primary distinction between the two decisions had to do with the weight given to race in affirmative action admissions policies. Nonetheless, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor had high hopes for such programs.

"We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today," O'Connor wrote for the majority in Grutter.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, while recognizing the University's complex policy, reiterated O'Connor's sentiments in Fisher.

"The Court's affirmance of the University's admissions policy today does not necessarily mean the University may rely on that same policy without refinement," Kennedy wrote for the majority opinion. "It is the University's ongoing obligation to engage in constant deliberation and continued reflection regarding its admission policies."

Racial affirmative action doesn't undermine merit

"I'm hoping that they'll completely take race out of the issue in terms of admissions and that everyone will be able to get into any school that they want no matter what race they are but solely based on their merit and they work hard for it," Fisher told the New York Times in 2012.

But does race inherently undermine an admit's qualifications?

The question itself is dubious considering the fact that other forms of affirmative action, including gender, are rarely mentioned. The aforementioned CCES survey, which only asked about racial affirmative action, is just one example.

Yet it's a widespread assumption that even Justice Antonin Scalia brought to the fore last December during oral arguments for the Fisher case. He asserted that affirmative action hurts African-American students by putting them in elite institutions they are not prepared for. Study after study shows there's simply no evidence for the claim.

A look at the effects of affirmative action bans also suggests the idea is based on a false dichotomy. Since California passed Prop 209 in 1996 barring racial considerations for college admissions at public universities, UC Berkeley witnessed a significant drop in the number of black students, from 8 percent pre–Prop 209 to an average of 3.6 percent of the freshman class from 2006 to 2010.

But that drop isn't necessarily tied to underqualified students of color. Rather, 58 percent of black students admitted from 2006 to 2010 rejected Berkeley's offer of admission. Alumni, administrators, and current students noted that a possible reason could be a feeling of isolation, or lack of other students of color, at UC's flagship campus — an ironic consequence of the affirmative action ban.

Asian-American applicants also challenge the colorblind meritocracy myth. According to a sociological study in 2009, white applicants were three times more likely to be admitted to selective schools than Asian applicants with the exact same academic record. And a 2013 survey found that white adults in California deemphasize the importance of test scores when Asian Americans, whose average test scores are higher than white students, are considered.

Furthermore, existing race-neutral admissions policies like legacy admissions show that taking race out of the equation doesn't make admissions processes any more just.

According to a 2011 study by the Chronicle of Higher Education, a review of 30 elite universities' admissions processes found that a legacy connection gave an applicant a 23.3 percentage point advantage over a non-legacy applicant. For applicants who had a parent who was an alum, the average advantage was 45.5 percentage points.

Many college campuses, however, have historically had predominantly white student bodies — 84 percent of college students in the US were white in 1976 compared with only 60 percent in 2012 — which makes it far more likely that the beneficiaries of legacy admissions practices are white applicants like Fisher, whose sister and father went to UT Austin.

Fisher advocated for a colorblind, meritocratic admissions process for which she, as an individual, may still not have been qualified. But a look at the marginalized group that has most benefited from affirmative action shows that race was never a barrier for that group to begin with.

White women, like Fisher, stand as a testament to affirmative action's success. If anything, the dismantling of affirmative action is launched at people of color, but it affects white women, too. And the willingness to erase them from the story is part of the problem.

The University of Texas Austin was Abigail Fisher's dream school. Fisher, from Sugar Land, Texas, a wealthy Houston suburb, earned a 3.59 GPA in high school and scored an 1180 on the SATs.

Not bad, but not enough for the highly selective UT Austin in fall 2008; Fisher's dreams were dashed when she was denied admission.

In response, Fisher sued. Her argument? That applicants of color, whose racial backgrounds were included as a component of the university's holistic review process, were less-qualified students and had displaced her.

Students graduating in the top 10 percent of any Texas high school are granted an automatic spot at UT Austin. Other students are evaluated through a holistic review process including a race-blind review of essays and creating a personal achievement score based on leadership potential, honors and awards, work experience, and special circumstances that include socioeconomic considerations such as race.

A few are accepted through provisional slots that include attending a summer program prior to the fall. One black student, four Latino students, and 42 white students with lower scores than Fisher were accepted under these terms. Also rejected were 168 African-American and Latino students with better scores than Fisher.

According to court documents, even if Fisher had received a perfect personal achievement score that included race (which, in itself, oversimplifies the admissions process), she still would not have necessarily qualified under UT's admission rubric.

In fact, when she applied for the class of 2012, the admission rate for non-automatic admits was more competitive than that of Harvard University.

Nonetheless, Fisher spent the past seven years in court, and Thursday the US Supreme Court ruled 4-3 that UT's admissions policy procedures are constitutional.

But the battle to erase race from the application review process for admission comes with an interesting paradox: "The primary beneficiaries of affirmative action have been Euro-American women," wrote Columbia University law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw for the University of Michigan Law Review in 2006.

A 1995 report by the California Senate Government Organization Committee found that white women held a majority of managerial jobs (57,250) compared with African Americans (10,500), Latinos (19,000), and Asian Americans (24,600) after the first two decades of affirmative action in the private sector. In 2015, a disproportionate representation of white women business owners set off concerns that New York state would not be able to bridge a racial gap among public contractors.

A 1995 report by the Department of Labor found that 6 million women overall had advances at their job that would not have been possible without affirmative action. The percentage of women physicians tripled between 1970 and 2002, from 7.6 percent to 25.2 percent, and in 2009 women were receiving a majority of bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees, according to the American Association of University Women. To be clear, these numbers include women of all races; however, breaking down affirmative action beneficiaries by race and gender seems to be rare in reported data.

Contrary to popular belief, affirmative action isn't just black. It's white, too. But affirmative action's white female faces are rarely at the center of the conversation.

---

White women have become some of affirmative action's fiercest opponents

In general, women today are more educated and make up more of the workforce than ever before, in part because of affirmative action policies. Indeed, from the tech industry to publishing, diversity has emerged as an overwhelming increase in the presence of white women, not necessarily people of color.

Incidentally, over the years white women have become some of affirmative action's most ardent opponents.

According to the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, nearly 70 percent of the 20,694 self-identified non-Hispanic white women surveyed either somewhat or strongly opposed affirmative action.

White women have also been the primary plaintiffs in the major Supreme Court affirmative action cases, with the exception of the first — Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978 — that was brought to the courts by a white man.

Twenty-five years after Bakke found that race can be one but not the only criterion for evaluating admissions applications, four white women have filed lawsuits seeking retribution for admissions rejections based on the premise that they were denied a spot over less-deserving students of color.

The first successful case to challenge affirmative action policy was Hopwood v. Texas in 1996. Cheryl Hopwood claimed that despite excellent scores and fitting the profile of a surefire admit, the University of Texas School of Law admitted 62 people of color, only nine of whom had better LSAT and GPA scores than she did.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that diversity alone was not enough to justify racial preferences. For example, only Mexican-American and African-American students' racial backgrounds were taken into consideration at UT's law school. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case, but the decision dismantled UT's earlier racial affirmative action policy and catalyzed UT's 10 percent policy to admit the best students in a state that still suffers from de facto segregation according to UT's Supreme Court briefs for the Fisher case.

But in 2003, two other white women approached the Court in parallel cases citing a misuse of race in admissions policies. In Grutter v. Bollinger, Barbara Grutter argued that she was denied admission to the University of Michigan Law School as a direct result of the law school's consideration of race in the admissions process. In Gratz v. Bollinger, Jennifer Gratz argued similarly that she was denied acceptance to the University of Michigan's flagship university in Ann Arbor as an undergrad because of race.

The Supreme Court decisions were split between the two cases. In Gratz, the justices ruled that race was being valued in ways that violated the Constitution's Equal Protection Clause — students received 20 points if they were from an underrepresented racial group compared with 5 points for artistic achievement. However, the justices ruled in Grutter that there was nothing unconstitutional about the way race was included in the law school's holistic admissions policy.

The primary distinction between the two decisions had to do with the weight given to race in affirmative action admissions policies. Nonetheless, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor had high hopes for such programs.

"We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today," O'Connor wrote for the majority in Grutter.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, while recognizing the University's complex policy, reiterated O'Connor's sentiments in Fisher.

"The Court's affirmance of the University's admissions policy today does not necessarily mean the University may rely on that same policy without refinement," Kennedy wrote for the majority opinion. "It is the University's ongoing obligation to engage in constant deliberation and continued reflection regarding its admission policies."

Racial affirmative action doesn't undermine merit

"I'm hoping that they'll completely take race out of the issue in terms of admissions and that everyone will be able to get into any school that they want no matter what race they are but solely based on their merit and they work hard for it," Fisher told the New York Times in 2012.

But does race inherently undermine an admit's qualifications?

The question itself is dubious considering the fact that other forms of affirmative action, including gender, are rarely mentioned. The aforementioned CCES survey, which only asked about racial affirmative action, is just one example.

Yet it's a widespread assumption that even Justice Antonin Scalia brought to the fore last December during oral arguments for the Fisher case. He asserted that affirmative action hurts African-American students by putting them in elite institutions they are not prepared for. Study after study shows there's simply no evidence for the claim.

A look at the effects of affirmative action bans also suggests the idea is based on a false dichotomy. Since California passed Prop 209 in 1996 barring racial considerations for college admissions at public universities, UC Berkeley witnessed a significant drop in the number of black students, from 8 percent pre–Prop 209 to an average of 3.6 percent of the freshman class from 2006 to 2010.

But that drop isn't necessarily tied to underqualified students of color. Rather, 58 percent of black students admitted from 2006 to 2010 rejected Berkeley's offer of admission. Alumni, administrators, and current students noted that a possible reason could be a feeling of isolation, or lack of other students of color, at UC's flagship campus — an ironic consequence of the affirmative action ban.

Asian-American applicants also challenge the colorblind meritocracy myth. According to a sociological study in 2009, white applicants were three times more likely to be admitted to selective schools than Asian applicants with the exact same academic record. And a 2013 survey found that white adults in California deemphasize the importance of test scores when Asian Americans, whose average test scores are higher than white students, are considered.

Furthermore, existing race-neutral admissions policies like legacy admissions show that taking race out of the equation doesn't make admissions processes any more just.

According to a 2011 study by the Chronicle of Higher Education, a review of 30 elite universities' admissions processes found that a legacy connection gave an applicant a 23.3 percentage point advantage over a non-legacy applicant. For applicants who had a parent who was an alum, the average advantage was 45.5 percentage points.

Many college campuses, however, have historically had predominantly white student bodies — 84 percent of college students in the US were white in 1976 compared with only 60 percent in 2012 — which makes it far more likely that the beneficiaries of legacy admissions practices are white applicants like Fisher, whose sister and father went to UT Austin.

Fisher advocated for a colorblind, meritocratic admissions process for which she, as an individual, may still not have been qualified. But a look at the marginalized group that has most benefited from affirmative action shows that race was never a barrier for that group to begin with.

White women, like Fisher, stand as a testament to affirmative action's success. If anything, the dismantling of affirmative action is launched at people of color, but it affects white women, too. And the willingness to erase them from the story is part of the problem.

Actually, It’s Not “OK to be White”

And if you knew the history of that concept you would understand why

Tim Wise - An Injustice!

march 2023

The last few days have seen the internet buzzing with talk about Scott Adams, the creator of the Dilbert comic strip, and the rant that has, as of now, seriously damaged his career.

His screed, which even in the best light was racially intemperate and ignorant, and in a more honest light, was flatly racist, concerned his overwrought reaction to a Rasmussen Reports poll, in which respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement:

“It’s OK to be white.”

As Adams pointed out, nearly half of Black folks polled either answered no or that they weren’t sure. To Adams, this means that roughly half of Black people are hostile or ambivalent to white people’s very existence.

To the Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh — ever looking to ramp up the absurdity for clicks and views — it was even worse: evidence that nearly half of all Blacks might be “genocidal” towards whites.

Yesterday I explained why Adams’s harangue, in which he called Black people a hate group and encouraged whites to “stay the hell away from them” based on this one poll, was both bigoted and so statistically inept as to boggle the mind.

But what I didn’t do was actually confront the question Rasmussen asked.

Oh sure, I explained it was a stupid question.

And I noted that it originated among white nationalist trolls and incel image board losers on 4Chan (I know that last part is redundant, sorry).

And yes, I explained that this origin and the trollish nature of the question is likely behind the way many Black people answered it (and large numbers of other people of color too, and even quite a few whites).

As many have pointed out, the social context within which such a question gets asked makes a difference: sort of like if someone were to ask: “Do white lives matter?”

The answer is obviously yes, but given that such a question is being asked against a backdrop of white backlash to the Black Lives Matter movement — and to deflect from addressing the longstanding reality of anti-Black racism — one might understandably think twice before endorsing this otherwise banal truism.

In any event, what I didn’t do in the previous piece, but want to do here, is offer a deeper response to the question, however absurd it was, and to make clear that depending on how you mean the question, the answer might well be no.

No, actually, it isn’t OK to be white.

There, I said it.

And if you follow along, though you may disagree, you’ll at least understand why someone could answer that way without harboring any hatred or antipathy for people classified as white.

It’s why I can say it, despite actually being white.

And yes, I know that to the white supremacists attacking me on Twitter — and these have, tellingly, been Adams’s loudest supporters there — my being Jewish means I’m not white. But actually, even under Hitlerian race law, I would have qualified, so make of that what you will.

Anyway, here’s the thing.

If the question is taken literally and at face value, the answer is yes, it is perfectly fine to be white.

No one gets to pick the racial identity group into which they are born. If one is white, one simply is and is due neither credit nor blame for such a thing. As such, it makes no sense to dislike someone solely for being white.

Your race is a function of how your society — in this case, the U.S. — has chosen to classify you and cluster people with your ancestry by so-called racial group. Just as ancestry is something over which you have no control (and thus, shouldn’t be disliked), the classification scheme also existed before you were born. As such, you can’t control it either.

And if the Rasmussen question were that simple, we could be done with it.

But it’s not.

There is another way to think about, and thus, to answer the question — a way that compels us to address the underlying issue embedded therein: namely, what does it mean to be white, and how did we become white in the first place?

Because unlike our being born into the designation or automatically inheriting our ancestry, that was hardly a natural process.

So, instead of emphasizing whether it’s OK to be white, what if we focused on whether it was OK to be white?

A semantic difference? Mere wordplay, like when Bill Clinton said the existence of his affair with Monica Lewinsky depended on what the meaning of “is” is?

Hardly.

To be white is something that was done to those who are now called such.

To be white is something that simply happens to us because of what was done.

And we can remain neutral about the latter while roundly condemning the former. Indeed, all people of goodwill should.

His screed, which even in the best light was racially intemperate and ignorant, and in a more honest light, was flatly racist, concerned his overwrought reaction to a Rasmussen Reports poll, in which respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement:

“It’s OK to be white.”

As Adams pointed out, nearly half of Black folks polled either answered no or that they weren’t sure. To Adams, this means that roughly half of Black people are hostile or ambivalent to white people’s very existence.

To the Daily Wire’s Matt Walsh — ever looking to ramp up the absurdity for clicks and views — it was even worse: evidence that nearly half of all Blacks might be “genocidal” towards whites.

Yesterday I explained why Adams’s harangue, in which he called Black people a hate group and encouraged whites to “stay the hell away from them” based on this one poll, was both bigoted and so statistically inept as to boggle the mind.

But what I didn’t do was actually confront the question Rasmussen asked.

Oh sure, I explained it was a stupid question.

And I noted that it originated among white nationalist trolls and incel image board losers on 4Chan (I know that last part is redundant, sorry).

And yes, I explained that this origin and the trollish nature of the question is likely behind the way many Black people answered it (and large numbers of other people of color too, and even quite a few whites).

As many have pointed out, the social context within which such a question gets asked makes a difference: sort of like if someone were to ask: “Do white lives matter?”

The answer is obviously yes, but given that such a question is being asked against a backdrop of white backlash to the Black Lives Matter movement — and to deflect from addressing the longstanding reality of anti-Black racism — one might understandably think twice before endorsing this otherwise banal truism.

In any event, what I didn’t do in the previous piece, but want to do here, is offer a deeper response to the question, however absurd it was, and to make clear that depending on how you mean the question, the answer might well be no.

No, actually, it isn’t OK to be white.

There, I said it.

And if you follow along, though you may disagree, you’ll at least understand why someone could answer that way without harboring any hatred or antipathy for people classified as white.

It’s why I can say it, despite actually being white.

And yes, I know that to the white supremacists attacking me on Twitter — and these have, tellingly, been Adams’s loudest supporters there — my being Jewish means I’m not white. But actually, even under Hitlerian race law, I would have qualified, so make of that what you will.

Anyway, here’s the thing.

If the question is taken literally and at face value, the answer is yes, it is perfectly fine to be white.

No one gets to pick the racial identity group into which they are born. If one is white, one simply is and is due neither credit nor blame for such a thing. As such, it makes no sense to dislike someone solely for being white.

Your race is a function of how your society — in this case, the U.S. — has chosen to classify you and cluster people with your ancestry by so-called racial group. Just as ancestry is something over which you have no control (and thus, shouldn’t be disliked), the classification scheme also existed before you were born. As such, you can’t control it either.

And if the Rasmussen question were that simple, we could be done with it.

But it’s not.

There is another way to think about, and thus, to answer the question — a way that compels us to address the underlying issue embedded therein: namely, what does it mean to be white, and how did we become white in the first place?

Because unlike our being born into the designation or automatically inheriting our ancestry, that was hardly a natural process.

So, instead of emphasizing whether it’s OK to be white, what if we focused on whether it was OK to be white?

A semantic difference? Mere wordplay, like when Bill Clinton said the existence of his affair with Monica Lewinsky depended on what the meaning of “is” is?

Hardly.

To be white is something that was done to those who are now called such.

To be white is something that simply happens to us because of what was done.

And we can remain neutral about the latter while roundly condemning the former. Indeed, all people of goodwill should.

opinion: White men refusing to share power is a silver stake piercing the heart of American democracy

John Stoehr - raw story

October 09, 2022

Thursday’s post borrowed a concept from a new history by Jeremi Suri called Civil War By Other Means. With it, I wrote about an either-or thinking seemingly ingrained in the Confederate brain.

When Black people were slaves, white people were free. When Black people were free, white people were slaves. Slavery wasn’t just the basis of the plantation economy. It was the basis of democracy for the well-mannered overlords of elite southern society. For them, without slavery – without suffering – civilization would collapse.

Among the many obvious problems with this way of thinking is something less obvious. If you believe that what’s bad for Black people is good for white people, what do you have when they, through means internal and external, achieve their freedom?

The answer is nothing.

There’s no there there. There’s no moral constitution that can go on in the absence of a social and political order built on Black bodies. Yes, not just slavery. Black bodies stacked up over centuries – were the foundation. Take them away? Civilization really does collapse.

Now apply this binary mode of thinking to a subject much in vogue these days thanks to redhat propagandists like Tucker Carlson. Of course, the subject I’m talking about is “The End of Men” or, as David Brooks put it more mildly, the “Crisis of Men and Boys.”

At the root of this subject is an assumption that, if given a hard look, would be seen as gonzo nuts. Anyone with eyes that can see – or senses that can sense – can discern that men, especially white men, are doing fine. To be sure, problems remain, societally and individually. But relative to others, white men are still on top.

Here’s an example: I’m 48, white, tall, bald. (Not bad looking.) When I go to pick up my daughter from school, where she’s in the racial minority, nonwhite parents, especially mothers, see me coming and hustle themselves and their kids out of the way, even apologizing as if they’ve done something wrong by standing still in public. This … just happens. It’s not natural, though. It’s a culture white men created.

That culture is complicated, but I think it boils down to this: white men deserve whatever they desire – money, sex, power, whatever.

This is somewhat scandalous to talk about openly, so we invented all sorts of ways of pretending that white men work as hard as other people do; that we aren’t the center of a political culture built for us centuries ago; and that we don’t accept at birth a rich inheritance.

Of course, we do.

The question is whether we want to know that we do.

Because if white men don’t know, what happens when they don’t get their heart’s desire? Some men turn inward to religion. Some to politics. But others don’t have what it takes to reconcile themselves to the consequences of democratic politics. So they reach for a gun.

Still, others discover ways to profit from telling these white men that democratic politics has cheated them of their birthright – that when women gain a fraction of an inch of political power, it’s castration; that when Black people succeed, in business or sports or politics, that’s a sign of societal disease and rot. It wasn’t this way back in the day. Something's gone terribly wrong. We gotta do something.

To be sure, propagandists like Carlson influence these men in various and sundry ways, but propaganda doesn’t work unless there’s already a kernel of truth to build on. In this case, there are two kernels.

One, as I said, is a political culture telling white men that they deserve everything. But the other is perhaps more important: an understanding, though likely unconscious, that if white men do not dominate – that if women and nonwhite people have equal political power as a consequence of democratic politics – what do they have?

Nothing.

They don’t have moral cores that exist independently of the lives and fortunes of their supposed inferiors, because the political culture permits them to grow up without bothering to develop moral cores. What do they have when women are strong and independent?

Due to either-or thinking, nothing.

Worse, they are nothing. Zeroes, ciphers, blanks.

That’s so terrifying, you’ll believe anything.

The reaction among Democrats and liberals, to things like the funny recommendation for men to beam red light onto their genitals, is by now conventional. We say that this wouldn’t happen if these men weren’t so sexist, so racist, so something-ist. If they only sought to be as “enlightened” as we are, this farce would be self-evident.

What some Democrats and liberals – especially Twitter hard*sses – don’t account for is that this reaction feeds into the either-or thinking that seeded a political culture at the root of the problem.

We keep telling them to not be something. But not being something terrifies them. The more we say don’t be X, the more they double down on being X. We see the former as the solution. They see the former as the problem. Either-or thinking becomes a vicious cycle.

Instead of telling them not to be something, we should tell them to be something. In other words, we should admonish them to develop a moral core – a rich inner life – that can exist independently without being conditioned on democratic politics. Instead of sharing power being seen as losing power, it would simply be seen as sharing it.

Developing such a thing is a heavy lift, though.

Living in your inheritance takes less effort.

When Black people were slaves, white people were free. When Black people were free, white people were slaves. Slavery wasn’t just the basis of the plantation economy. It was the basis of democracy for the well-mannered overlords of elite southern society. For them, without slavery – without suffering – civilization would collapse.

Among the many obvious problems with this way of thinking is something less obvious. If you believe that what’s bad for Black people is good for white people, what do you have when they, through means internal and external, achieve their freedom?

The answer is nothing.

There’s no there there. There’s no moral constitution that can go on in the absence of a social and political order built on Black bodies. Yes, not just slavery. Black bodies stacked up over centuries – were the foundation. Take them away? Civilization really does collapse.

Now apply this binary mode of thinking to a subject much in vogue these days thanks to redhat propagandists like Tucker Carlson. Of course, the subject I’m talking about is “The End of Men” or, as David Brooks put it more mildly, the “Crisis of Men and Boys.”

At the root of this subject is an assumption that, if given a hard look, would be seen as gonzo nuts. Anyone with eyes that can see – or senses that can sense – can discern that men, especially white men, are doing fine. To be sure, problems remain, societally and individually. But relative to others, white men are still on top.

Here’s an example: I’m 48, white, tall, bald. (Not bad looking.) When I go to pick up my daughter from school, where she’s in the racial minority, nonwhite parents, especially mothers, see me coming and hustle themselves and their kids out of the way, even apologizing as if they’ve done something wrong by standing still in public. This … just happens. It’s not natural, though. It’s a culture white men created.

That culture is complicated, but I think it boils down to this: white men deserve whatever they desire – money, sex, power, whatever.

This is somewhat scandalous to talk about openly, so we invented all sorts of ways of pretending that white men work as hard as other people do; that we aren’t the center of a political culture built for us centuries ago; and that we don’t accept at birth a rich inheritance.

Of course, we do.

The question is whether we want to know that we do.

Because if white men don’t know, what happens when they don’t get their heart’s desire? Some men turn inward to religion. Some to politics. But others don’t have what it takes to reconcile themselves to the consequences of democratic politics. So they reach for a gun.

Still, others discover ways to profit from telling these white men that democratic politics has cheated them of their birthright – that when women gain a fraction of an inch of political power, it’s castration; that when Black people succeed, in business or sports or politics, that’s a sign of societal disease and rot. It wasn’t this way back in the day. Something's gone terribly wrong. We gotta do something.

To be sure, propagandists like Carlson influence these men in various and sundry ways, but propaganda doesn’t work unless there’s already a kernel of truth to build on. In this case, there are two kernels.

One, as I said, is a political culture telling white men that they deserve everything. But the other is perhaps more important: an understanding, though likely unconscious, that if white men do not dominate – that if women and nonwhite people have equal political power as a consequence of democratic politics – what do they have?

Nothing.

They don’t have moral cores that exist independently of the lives and fortunes of their supposed inferiors, because the political culture permits them to grow up without bothering to develop moral cores. What do they have when women are strong and independent?

Due to either-or thinking, nothing.

Worse, they are nothing. Zeroes, ciphers, blanks.

That’s so terrifying, you’ll believe anything.

The reaction among Democrats and liberals, to things like the funny recommendation for men to beam red light onto their genitals, is by now conventional. We say that this wouldn’t happen if these men weren’t so sexist, so racist, so something-ist. If they only sought to be as “enlightened” as we are, this farce would be self-evident.

What some Democrats and liberals – especially Twitter hard*sses – don’t account for is that this reaction feeds into the either-or thinking that seeded a political culture at the root of the problem.

We keep telling them to not be something. But not being something terrifies them. The more we say don’t be X, the more they double down on being X. We see the former as the solution. They see the former as the problem. Either-or thinking becomes a vicious cycle.

Instead of telling them not to be something, we should tell them to be something. In other words, we should admonish them to develop a moral core – a rich inner life – that can exist independently without being conditioned on democratic politics. Instead of sharing power being seen as losing power, it would simply be seen as sharing it.

Developing such a thing is a heavy lift, though.

Living in your inheritance takes less effort.

The Racist History of Abortion and Midwifery Bans

Today’s attacks on abortion access have a long history rooted in white supremacy.

Michele Goodwin - ACLU

JULY 1, 2020

In 1851, Sojourner Truth delivered a speech best known as“Ain’t I A Woman?” to a crowded audience at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio. At the time, slavery remained in full force, a vibrant enterprise that fueled the American economy. Various laws protected that system, including the Fugitive Slave Act, which resulted in the abduction of “free” Black children, women, and men as well as those who had miraculously escaped to northern cities like Boston or Philadelphia. Bounty hunters then sold their prey to Southern plantation owners. The law denied basic protections for Black people caught in the greed-filled grasps of slavery.

Ms. Truth condemned this disgraceful enterprise, which thrived off not only uncompensated labor, but also physical and psychological terror. Most will remember Ms. Truth’s oration for its vivid descriptions regarding physical labor; Black women were forced to plough, plant, herd, and build — just as men. Yet far too little attention centers on her condemnation of that system, which made sexual chattel of Black women, and then cruelly sold off Black children. This was human trafficking in the American form, and it lasted for centuries. Ms. Truth pleaded:

“I have borne 13 children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

Following the Supreme Court’s decision in June Medical Services v. Russo this week, it is worth reflecting on the racist origins of the anti-abortion movement in the United States, which date back to the ideologies of slavery. Just like slavery, anti-abortion efforts are rooted in white supremacy, the exploitation of Black women, and placing women’s bodies in service to men. Just like slavery, maximizing wealth and consolidating power motivated the anti-abortion enterprise. Then, just as now, anti-abortion efforts have nothing to do with saving women’s lives or protecting the interests of children. Today, a person is 14 times more likely to die by carrying a pregnancy to term than by having an abortion, and medical evidence has shown for decades that an abortion is as safe as a penicillin shot—and yet abortion remains heavily restricted in states across the country.

Prior to the Civil War, abortion and contraceptives were legal in the U.S., used by Indigenous women as well as those who sailed to these lands from Europe. For the most part, the persons who performed all manner of reproductive health care were women — female midwives. Midwifery was interracial; half of the women who provided reproductive health care were Black women. Other midwives were Indigenous and white.