TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

History

truth is freedom

A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a

tree without roots

Marcus Garvey

tree without roots

Marcus Garvey

march 2023

what use to be

history you should know

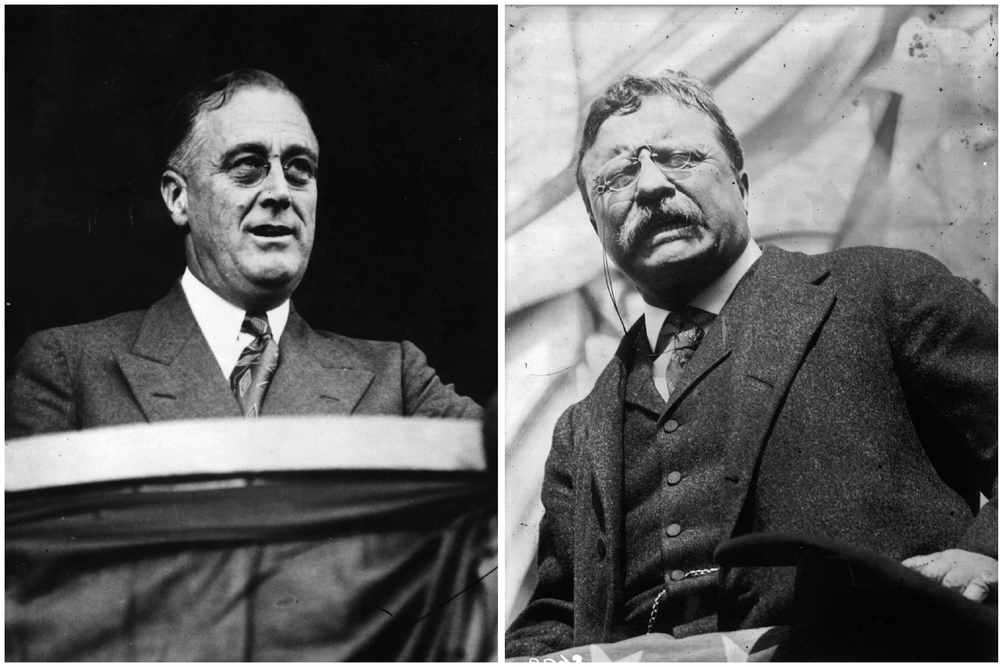

america's greatest traitors of 20th century

a traitor confesses!!!

A former Texas lawmaker, compelled by the news of President Jimmy Carter entering hospice care, has come forward to reveal that there was, in fact, a secret GOP effort in 1980 to prevent Iran from releasing more than 50 Americans hostages until after that year’s presidential election.

Former Texas Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes, 85, has told the New York Times that in the summer of 1980, he accompanied his mentor and one-time business partner, former Texas governor John Connally, on a trip to the Middle East during which Connally asked Arab leaders to communicate to Iranian officials that they should not release the hostages before Election Day because if they waited, Ronald Reagan would offer them a better deal. (Connally, at that point a former Democrat, is also known for being the other person seriously wounded during the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963.) The infamous hostage crisis, which began on November 4, 1979, and lasted 444 days, was an open political wound for Carter, who went on to lose his reelection bid to Reagan. After Iran released the hostages on Reagan’s Inauguration Day, there were immediate suspicions among Democrats that the Reagan team had somehow sabotaged the Carter administration’s efforts in order to deny Carter a late-campaign political win — which Reagan advisers famously dubbed a potential “October surprise.” The most prominent theories, like the one put forward by former Carter national security aide Gary Sick in the early 90s, alleged that William Casey, Reagan’s campaign chairman who went on to become the director of the CIA, had orchestrated the sabotage and made a deal with Iran, but as the Times notes, subsequent Congressional investigations never turned up proof. Barnes, a Democrat who was once the speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, told the Times that there was no doubt in his mind that the purpose of Connally’s trip was to get a message to Iran. He also said that they communicated with the Reagan team during the trip, and that after they returned to the U.S., Connally — who wanted to be Reagan’s Secretary of State — briefed Casey on the trip: Mr. Barnes said he was certain the point of Mr. Connally’s trip was to get a message to the Iranians to hold the hostages until after the election. “I’ll go to my grave believing that it was the purpose of the trip,” he said. “It wasn’t freelancing because Casey was so interested in hearing as soon as we got back to the United States.” Mr. Casey, he added, wanted to know whether “they were going to hold the hostages.” … They traveled to the region on a Gulfstream jet owned by Superior Oil. Only when they sat down with the first Arab leader did Mr. Barnes learn what Mr. Connally was up to, he said. Mr. Connally said, “‘Look, Ronald Reagan’s going to be elected president and you need to get the word to Iran that they’re going to make a better deal with Reagan than they are Carter,’” Mr. Barnes recalled. “He said, ‘It would be very smart for you to pass the word to the Iranians to wait until after this general election is over.’ And boy, I tell you, I’m sitting there and I heard it and so now it dawns on me, I realize why we’re there.” “History needs to know that this happened,” Barnes explained to the Times, “I think it’s so significant and I guess knowing that the end is near for President Carter put it on my mind more and more and more. I just feel like we’ve got to get it down some way.” Barnes said he had kept the details of the trip secret because he didn’t “want to look like Benedict Arnold to the Democratic Party.” Casey and Connally are no longer alive to comment on Barnes’s bombshell, but the Times confirmed Barnes accompanied Connally on a July 1980 trip to six countries in the Middle East, and spoke with four still-living people who Barnes had previously shared the story with. The Times report stresses that there is no evidence Reagan was aware of the effort, or that Casey directed it, but Barnes’s admission nonetheless provides compelling evidence that Reagan operatives — or at the very least, Connally — did in fact conspire against Carter and U.S. foreign policy for political gain, and may have prevented an earlier release for the hostages. RELATED:

An angry mob broke into a jail looking for a Black man—then freed him

He called himself Jerry. He was a skilled cabinetmaker in Syracuse, N.Y., before he got a better-paying job making wooden barrels. He was a light-skinned Black man with reddish hair in his early forties, and as far as anyone knew, he didn’t have any family.

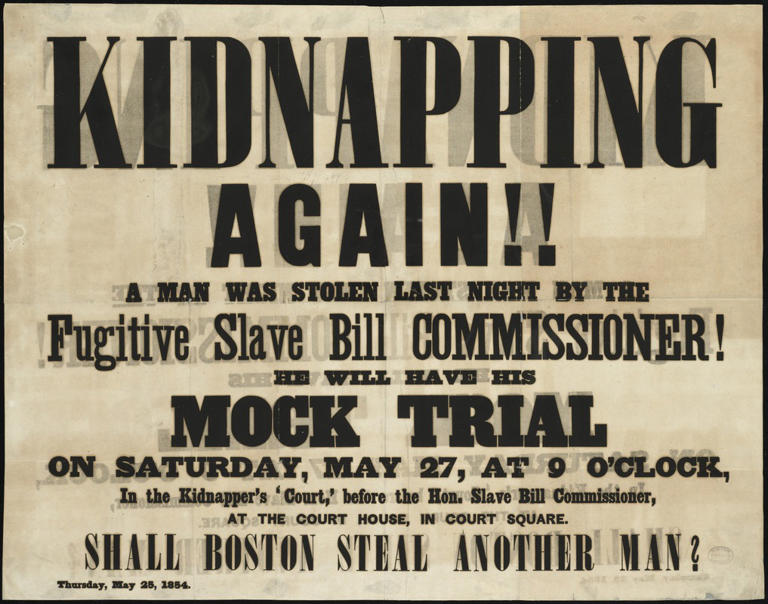

But in the eyes of the law, his name was William Henry, and he was another man’s property. On Oct. 1, 1851, the struggle against slavery in the United States centered on this man’s body, and his forceful liberation became a community holiday, “Jerry Rescue Day,” marked with poetry, song and fundraising. Since 1843, Jerry’s life had been marked by escape. First he fled his enslavement in Missouri. He may have also narrowly avoided recapture in Chicago and Milwaukee, according to one account. During the winter of 1849-1850, he arrived in Syracuse, a city well known for its strong antislavery bent. Even with the high number of White and Black abolitionist leaders and supporters living there, Jerry was still met with at least some racism from co-workers, who saw him as competition. He also had a few run-ins with the law, getting arrested for theft and assault. It isn’t clear how much truth there was to the charges; in any case, he was always soon released. In late 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, making escape from slavery a federal matter and requiring assistance from local officials in any state, including ones where slavery was illegal. Daniel Webster, a Northern politician who supported the law, predicted a confrontation over its enforcement would happen in Syracuse, according to historian Angela F. Murphy, who wrote a book about the rescue. “He gives this really thundering speech about how the Fugitive Slave Law would be enforced, even in Syracuse,” Murphy told The Washington Post. “He said even at the next national antislavery convention” — set for October in Syracuse — “it’s going to be enforced.” As September gave way to October, the city was packed, not only with hundreds of abolitionists there for the convention but also with thousands of farmers and their families in town for the county fair. Jerry was working through his lunch break when local police and federal marshals came to detain him. At first, he didn’t resist, probably figuring it would go like his other arrests. Then they arrived at a federal commissioner’s office, and he recognized a White neighbor of his former enslaver. Jerry had been sold in absentia, and the new owner had sent the neighbor up to collect his property. By this point, a lot of Northern cities had “vigilance committees” — multiracial groups that kept an eye out for slave catchers. One of these committee members spotted Jerry on the way to the office and ran to the church where the convention was being held. Soon, church bells across the city were ringing to alert the whole town. As a crowd gathered outside the office, prominent abolitionists like Gerrit Smith, Rev. Samuel J. May and Rev. Jermain Wesley Loguen — himself a fugitive slave — along with a handful of lawyers pushed their way inside to aid Jerry at a hearing. There isn’t much they could have done, legally speaking, and most likely everyone knew it. Before the hearing could even get going, members of the vigilance committee made a first attempt to free Jerry, taking advantage of the chaotic and crowded room to push him outside. He ran down the street, still handcuffed. Authorities caught up to him, roughed him up and tried to take him back to the hearing. A fight broke out between police and the crowd, both sides pulling on Jerry’s body until his clothes were torn off. Eventually, police dragged him, bloodied, back into a cell, where they added leg irons. The sight of the brutality “actually turn[ed] some people into supporters of the move to rescue him,” Murphy said. Many White residents at the time opposed slavery but preferred a gradual, legal approach rather an immediate emancipation that almost by definition required violence, or at least the threat of it. Jerry began to scream. He shouted. He begged for the crowd outside to help him. He was “in a perfect rage, a fury of passion,” May, the abolitionist and a Unitarian minister, recalled later. May was allowed in the cell to calm Jerry, which didn’t work until May made it clear another attempt to free him was in the works. The hearing resumed at 5:30 p.m. Jerry’s attorneys began raising objections to anything they could to slow it down. Outside, the sun was low in the sky, and the crowd had grown to thousands. Rocks began flying through the windows. After a rock flew past his head, the commissioner adjourned the hearing until the next morning. Still, the crowd did not disperse; it grew. Some arrived with weapons, others picked up an ax or iron rod from a nearby hardware store with an abolitionist owner. A battering ram appeared. At 8:30 p.m., someone shouted, “Now!” They smashed windows, rammed the doors and pulled bricks right out of the building’s walls. The marshals inside got off a shot or two, hitting no one, before basically giving up. No one was killed, though one marshal suffered a broken arm when he jumped out of a second-story window. Another, hiding inside the cell with the prisoner, opened the door and pushed Jerry out. The rescuers carried Jerry to a waiting carriage, which rushed him out of town to a safe house, where his chains were removed. Soon he was on the Underground Railroad to Canada, and safety. Though it hasn’t been a feature of too many history textbooks, the “Jerry Rescue” was national news at the time. In general, Syracuse residents were happy about it, jokingly asking, “Where’s Jerry?” as they passed one another on the street. More than a dozen organizers were eventually indicted, including Loguen, who fled to Canada. He denied the charges and even said he would return to stand trial if authorities would promise not to send him back into slavery. “Jerry Rescue Day” became a feather in abolitionist Syracuse’s cap — residents had defied the Fugitive Slave Act and won! — and the city still memorializes the incident with a statue. This mob, which broke into a jail to liberate rather than lynch, was not unique. Harriet Tubman herself helped storm a jail to free Charles Nalle near Troy, N.Y., in 1860. In 1854 in Milwaukee, abolitionists stormed a jail and freed Joshua Glover, a formerly enslaved man who had been living in nearby Racine for years. And in Boston that same year, thousands rioted after a failed attempt to free a young man named Anthony Burns. His forced return to Virginia solidified opposition to slavery for many Bostonians, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. “We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and waked up stark mad Abolitionists,” one observer wrote. (Burns was later sold to abolitionists and freed.) Usually, the violence of the Civil War is said to have begun on April 12, 1861, with shots fired at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. But perhaps it really started with these battles in the North, where the fight for a man’s freedom could not have been more literal. american democracy!!!

Reversing Roe v. Wade goes against the will of the people. A recent Quinnipiac poll shows that a clear majority support the Supreme Court ruling ensuring a patient’s access to abortion care. That, of course, won’t stop opponents to the measure from ruling by minority; it’s exactly what the so-called “pro-lifers” want.

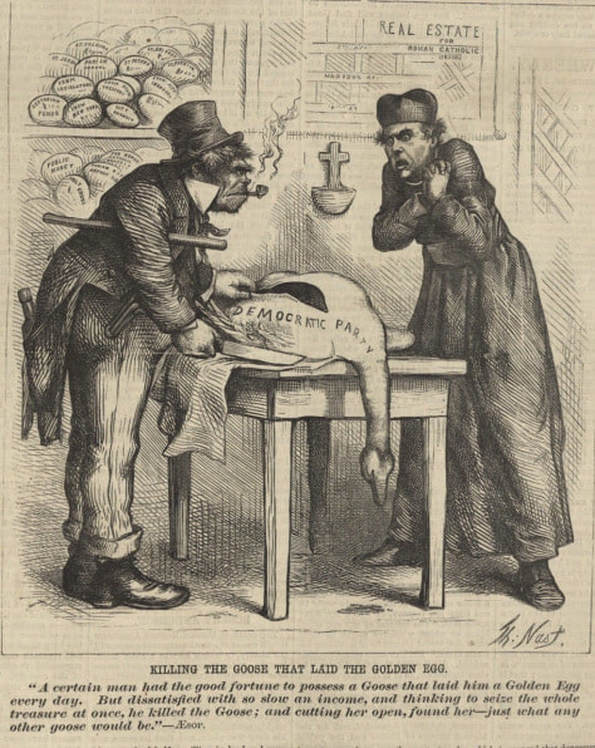

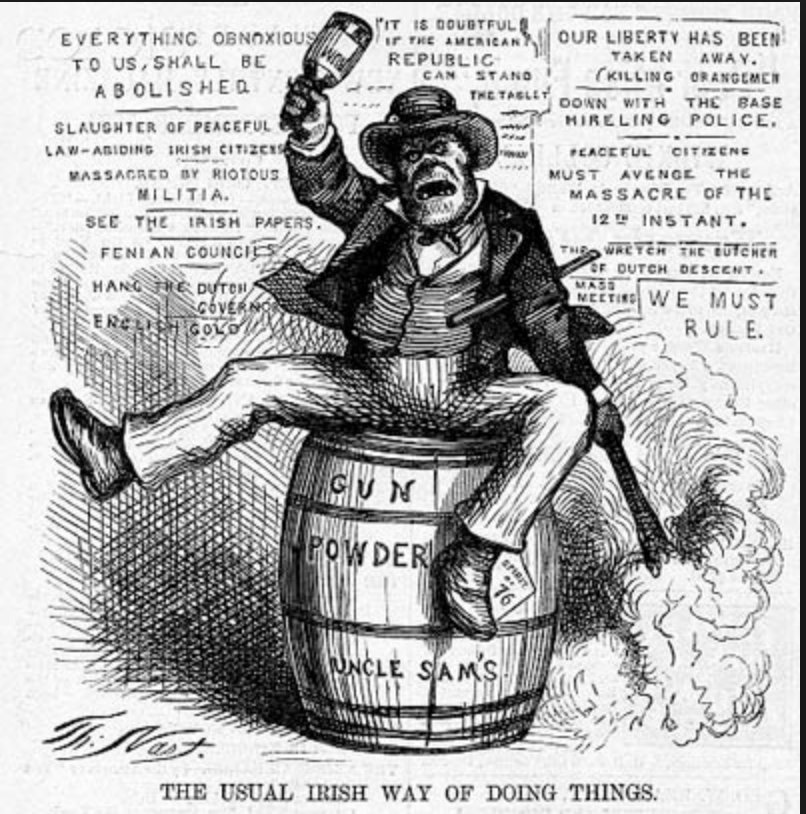

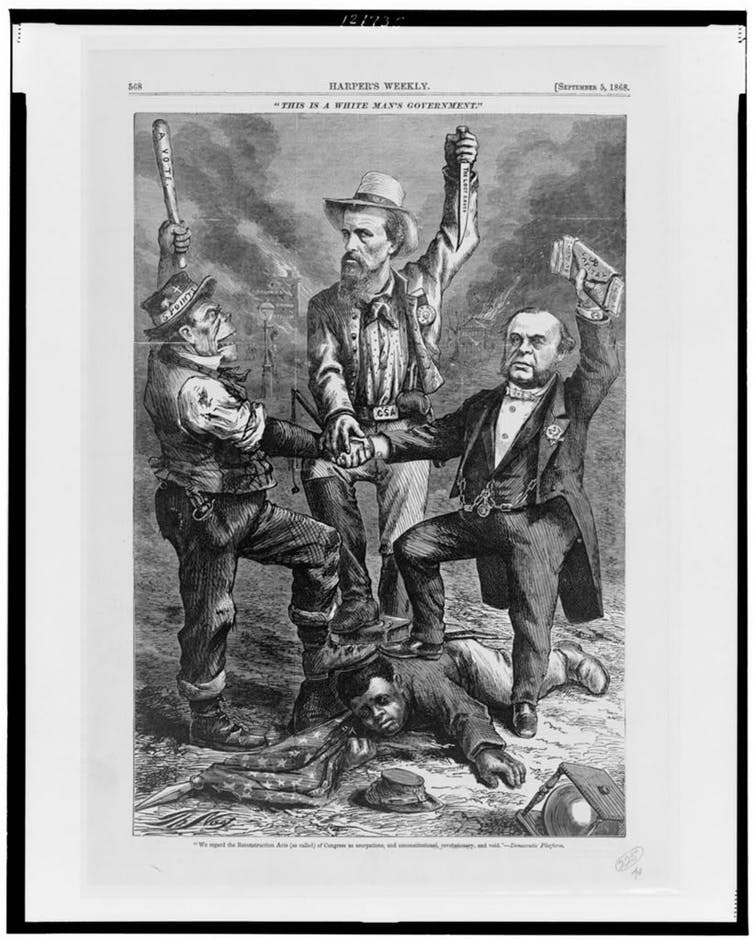

Rule by minority has increasingly become the Republican’s modus operandi; gerrymandering, voter suppression, and congressional loopholes show they are not shy about staying in power by any means necessary. Now we’re seeing what’s possible when a man like Donald Trump embraces it as the leader of the power. Trump has not hesitated to embrace white nationalists and give racists power—just look at Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller, and Jeff Sessions—which is exactly why it’s prime time for Roe v. Wade to come up on the chopping block. It’s no coincidence that the biggest national threat to abortion rights since Roe is happening under such a racist government. Have you ever wondered why the “pro-life” movement is so … white? Or perhaps you’ve noticed that they seem incapable of not being racist whenever they pretend to care about Black people to further their extreme agenda. You’re not alone. It turns out that the pro-life movement has been very good about hiding its racist origins. That’s not just because white people tend to be uncomfortable and avoidant when talking about race. It’s because it also exposes the true goal of the movement, which makes their initially confusing hypocrisy incredibly clear. Fundamentalist Christians and [the KKK] are pretty close, fighting for God and country. Someday we may all be in the trenches together in the fight against the slaughter of unborn children. — John Burt, 1994 New York Times interview. Abortion restrictions have always been political—and about raceDuring much of the 19th century, abortion was unregulated and business was booming. The industry was doing so well that one famous provider, Madame Restell, invested in one of New York City’s first luxury apartment buildings with her husband. The white, middle-class women who could afford abortions were having more control of their bodies and thus having fewer children. This was all happening while the United States was also getting more Catholic and Jewish immigrants. The fears of white women increasingly turning away from doing their “duty” to bear children coupled with xenophobia compelled powerful white men to spring into action. Under the guise of wanting to require a medical license to perform abortions, the American Medical Association (AMA) ran a successful campaign to ban abortion care and put the decision to make exceptions completely in their hands. How did they succeed? They appealed to the racist little hearts of Anglo-Saxon politicians. Back then, “pro-life” racism wasn’t as subtle. The authors of “Abortion, Race, and Gender in Nineteenth-Century America” in the American Sociological Review wrote that “physicians argued that middle-class, Anglo-Saxon married women were those obtaining abortions, and that their use of abortion to curtail childbearing threatened the Anglo-Saxon race.” Take this excerpt from a book by Dr. Augustus K. Gardner from 1870, for example: Infanticide is no new crime. Savages have existed in all times, and abortions and destruction of children at and subsequent to birth have been practiced among all barbarous nations of antiquity … The savages of past ages were not better than the women who commit such infamous murders to-day, to avoid the cares, the expense or the duty of nursing and tending a child. Here we see how framing abortion as murder came from racist propaganda. Dr. Gardner talked about barbaric peoples—Indians, Greeks, and Chinese, for example—that supposedly partook in infanticide. He uses this in an attempt to shame women from seeking abortions, calling them no better than these “savages.” Political anti-abortion rhetoric began with this message: abortion is for other people. Non-white people. Yet even back then, there was no consensus among conservatives or Christians about abortion’s morality. However, the disproportionate amount of power that rich white men had in the country—as doctors and politicians—allowed this minority to execute its will on the people (sound familiar?). While the 19th century racists succeeded in getting a nationwide abortion ban, that pesky desire from women for autonomy kept rearing its head. It’s almost as if you keep oppressing people, they will eventually want more rights—no matter how hard you try! No wonder they hated Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood. She published a feminist magazine in 1914 that advocated for reproductive freedom—exactly what racist white men didn’t want embraced by women. The smears and attacks against her continue today as conservatives try to paint her as the racist. The truth is that she was a proponent of eugenics, but was staunchly against its use for racist means. At the Jewish Woman’s Archive, Open Society Institute fellow Ellen Chasler explains: She distinguished between individual applications of eugenic principles and cultural ones and spoke out against immigration prohibitions that promoted ethnic or racial stereotypes with a biological rationale. She saw birth control as an instrument of social justice, not of social control.” In fact, Sanger worked with activists of color like W.E.B. Du Bois and Japanese feminist Shizue Kato—people conservatives today would undoubtedly disparage. Dr. Martin Luther King even once said, “There is a striking kinship between our [civil rights] movement and Margaret Sanger’s early efforts in “Family Planning—A Special and Urgent Concern.” While there’s no excuse for Sanger’s support of the eugenics movement, it does show that the fact was distorted by a white racist movement that undoubtedly has people who would agree with her eugenic statements today. Even in Sanger’s time, white supremacists still couldn’t agree on whether to support birth control or not. Some saw it as a possible means to keep “undesirables” from reproducing, while other had fears that Anglo-Saxon white women would embrace it too much and significantly lower their birth rate. --- How racism brought Republicans and white evangelicals together Evangelical leaders tried to influence Carter to seek a constitutional amendment to overturn Roe v. Wade. He refused, so they looked to the other party. The Republican Party’s sexism dovetailed nicely with racist anti-abortion policies and support for such an amendment was made a part of the party’s platform. And thus, the GOP officially adopted the language proposed by the power-hungry white evangelicals and officially became the “pro-life” party with candidate Ronald Reagan as the leader. Reagan was a good bet. He had name recognition with his acting career before entering politics. And, like Falwell and friends, Reagan lamented the advancement of the civil rights for Black people. Reagan had no problem catering to racists, pushing the “welfare queen” myth and calling the Voting Rights Act “humiliating to the South.” Oh, and he was endorsed by the KKK—twice. At first glance, Reagan seemed to be the least likely ally for the anti-choice movement. When he was California’s governor, he signed the country’s least restrictive abortion access bill in the country. Carter had a documented history of being anti-abortion, both in his personal and political life. However, it’s Carter’s refusal to bend to the political will of the powerful white evangelical men that was seen as the biggest liability. Reagan’s landslide win solidified the religious right’s political strength. Falwell, Dobson, and Weyrich had succeeded in making their racist political goals viable enough to get millions to vote for their preferred candidate who’d get rid of abortion and keep the brown and Black people from taking over. Since then, the political power of white evangelicals in the United States has only gotten stronger.

|

...Mentioning my research to others repeatedly provoked questions about Africa, not America. They obviously assumed that a scholar working on the slave trade must be working on the trade that brought millions of Africans to the Western Hemisphere via the terrifying Atlantic Ocean crossing known as the Middle Passage.

They did not appear to know that by the time slavery ended in 1865, more than 1 million enslaved people had been forcibly moved across state lines in their own country, or that hundreds of thousands more had been bought and sold within individual states.

Americans continue to misunderstand how slavery worked and how vast was its reach – even as the histories of race and slavery are central to ongoing public conversations.

Indifference to suffering

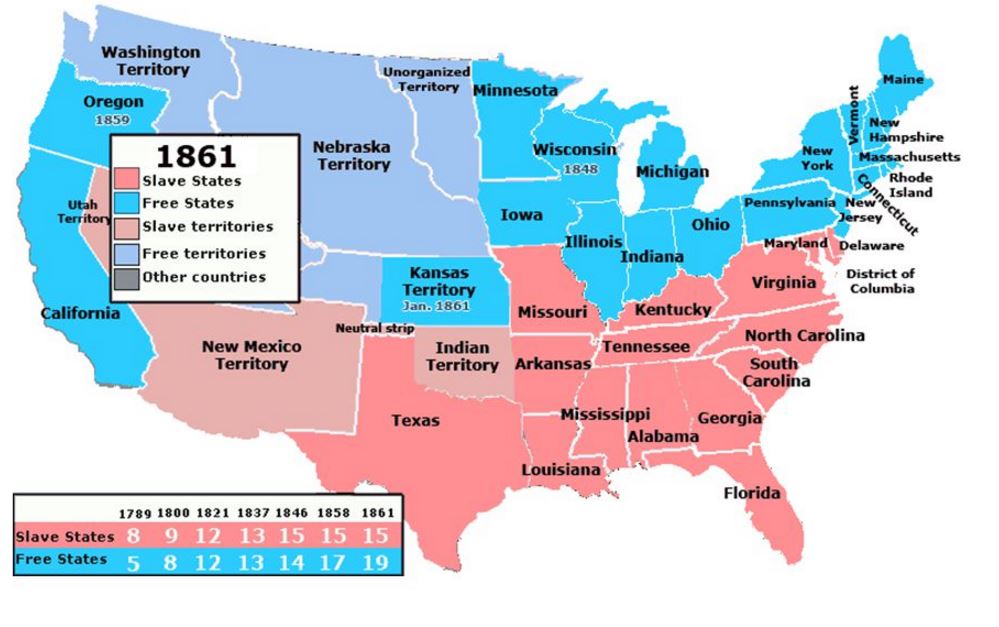

Enslaved people were bought and sold within the boundaries of what is now the United States dating back to the Colonial era. But the domestic slave trade accelerated dramatically in the decades after 1808.

That year, Congress outlawed the importation of enslaved people from overseas, and it did so at a moment when demand for enslaved laborers was booming in expanding cotton and sugar plantation regions of the lower South.

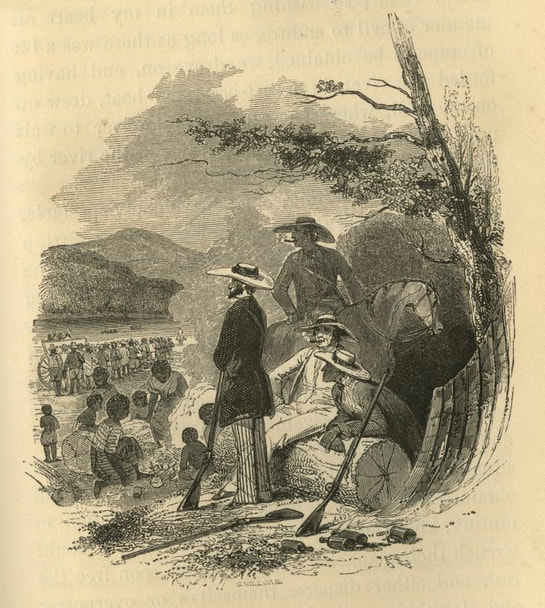

Growing numbers of professional slave traders stepped forward to satisfy that demand. They purchased enslaved people primarily in upper South states like Maryland and Virginia, where a declining tobacco economy left many slaveholders with a surplus of laborers. Traders then forced those enslaved people to migrate hundreds of miles over land and by ship, selling them in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and other states where traders hoped to turn a profit.

The domestic slave trade was a brutal and violent business. Enslaved people lived in constant fear that they or their loved ones would be sold.

William Anderson, who was enslaved in Virginia, remembered seeing “hundreds of slaves pass by for the Southern market, chained and handcuffed together.” Years after he fled the South, Anderson wrote of “wives taken from husbands and husbands from wives, never to see each other again – small and large children separated from their parents,” and he never forgot the sounds of their sorrow. “O, I have seen them and heard them howl like dogs or wolves,” he recalled, “when being under the painful obligation of parting to meet no more.”

Slave traders were largely indifferent to the suffering they caused. Asked in the 1830s whether he broke up slave families in the course of his operations, one trader admitted that he did so “very often,” because “his business is to purchase, and he must take such as are in the market.”

‘So wicked’

Domestic slave traders initially worked mostly out of taverns and hotels. Over time, an increasing number of them established offices, showrooms and prisons where they held enslaved people whom they intended to sell.

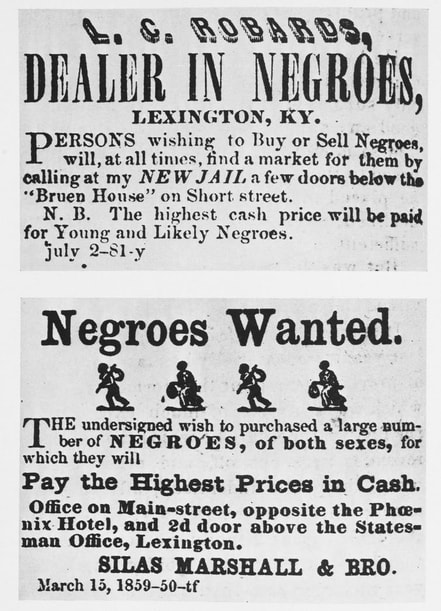

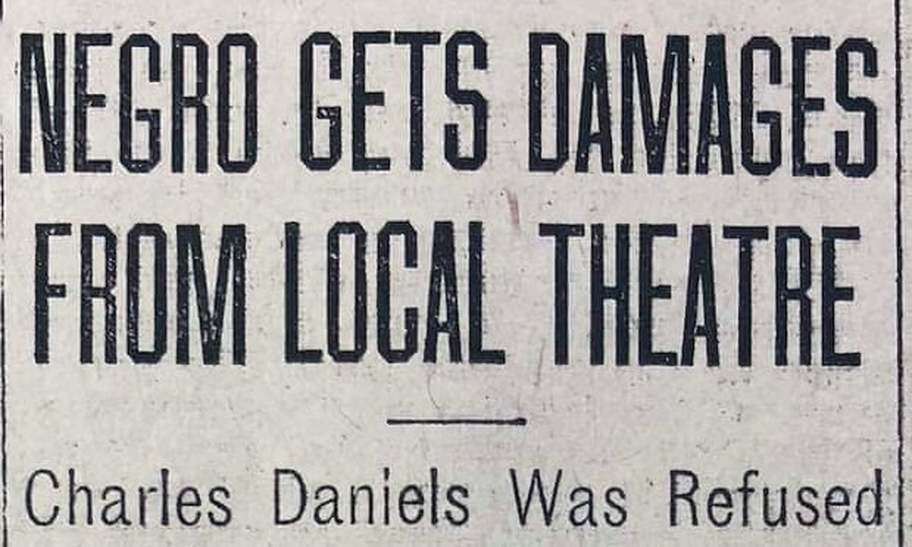

By the 1830s, the domestic slave trade was ubiquitous in the slave states. Newspaper advertisements blared “Cash for Negroes.” Storefront signs announced that “dealers in slaves” were inside. At ports and along roads, travelers reported seeing scores of enslaved people in chains.

Meanwhile, the money the trade generated and the credit that financed it circulated throughout the country and across the Atlantic, as even European banks and merchants looked to share in the gains.

The more visible the trade became, the more antislavery activists made it a core of their appeals. When abolitionist editor Benjamin Lundy, for example, asked white Americans in the 1820s how long they could look at the slave trade and “permit so disgraceful, so inhuman, and so wicked a practice to continue in our country, which has been emphatically termed THE HOME OF THE FREE,” he was one among a rising chorus.

But abolitionists made little headway. The domestic slave trade ended only when slavery ended in 1865.

Propaganda obscures history

Vital to the American economy, important to American politics and central to the experience of enslaved people, the domestic slave trade was an atrocity carried out on a massive scale. As British traveler Joseph Sturge noted, by the 1840s, the entire slaveholding portion of the United States could be characterized by division “into the ‘slave-breeding’ and ‘slave-consuming’ States.”

Yet popular historical knowledge of the domestic trade remains hazy, thanks largely to purposeful forgetting and to a propaganda campaign that began before the Civil War and continued long past its conclusion.

White Southerners made denial about the slave trade an important tenet in their defense of slavery. They claimed that slave sales were rare, that they detested the slave trade and that traders were outcasts disdained by respectable people.

Kentucky minister Nathan Lewis Rice’s assertion in 1845 that “the slave-trader is looked upon by decent men in the slave-holding States with disgust” was such a common sentiment that even white Northerners sometimes parroted it. Nehemiah Adams, for example, a Massachusetts resident who visited the South in 1854, came away from his time in the region believing that “Negro traders are the abhorrence of all flesh.”

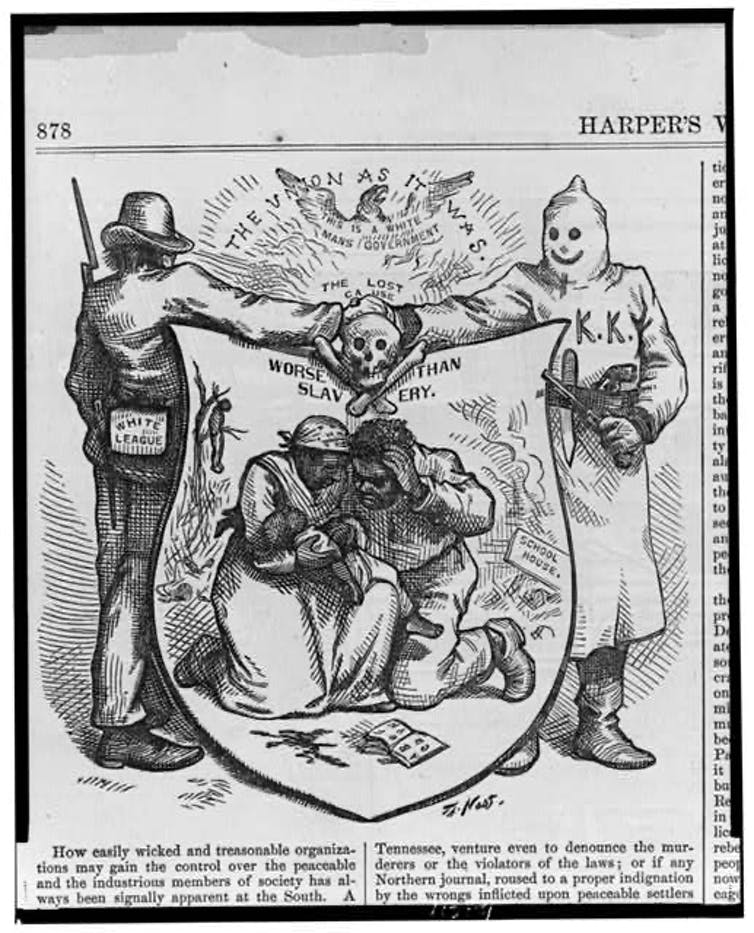

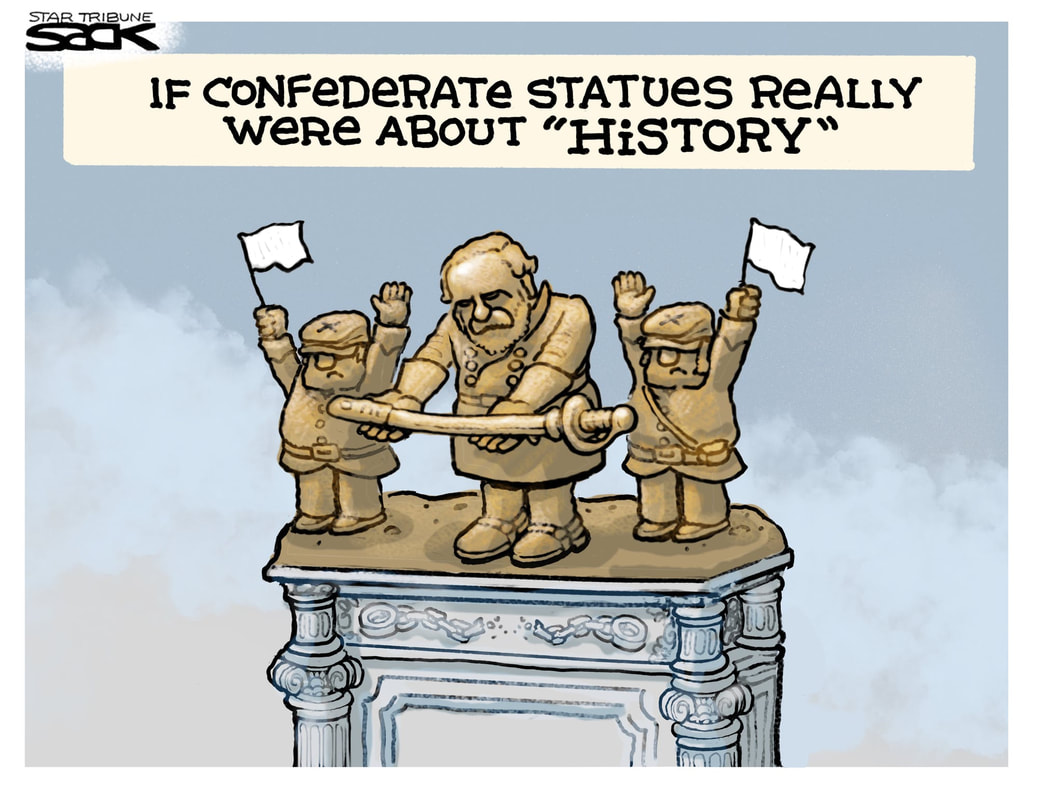

Such claims were almost entirely lies. But downplaying the slave trade became a standard element of the racist mythology embedded in the defense of the Confederacy known as the Lost Cause, whose purveyors minimized slavery’s significance as they discounted its role in bringing about the Civil War.

And while the Confederacy may have lost on the battlefield, its supporters arguably triumphed in the cultural struggle to define the war and its meaning. Well into the 20th century, significant numbers of white Americans throughout the country accepted and embraced the notion that slavery had been relatively benign.

As they did so, the devastations of the domestic slave trade became buried beneath comforting fantasies of moonlight and magnolias evoked by movies like “Gone With the Wind.”

Recent years have seen monuments to the Confederacy coming down in cities and towns across the country. But the struggle over how Americans remember and talk about slavery, now perhaps more heated and controversial than ever, arguably remains stuck in terms that are legacies of the Lost Cause.

Slavery still conjures images of Southern farms and plantations. But the institution was grounded in the sales of nearly 2 million human beings in the domestic slave trade, the profits from which nurtured the economy of the entire country.

Until that history makes its way more deeply into our popular memory, it will be impossible to come to terms with slavery and its significance for the American past and present.

They did not appear to know that by the time slavery ended in 1865, more than 1 million enslaved people had been forcibly moved across state lines in their own country, or that hundreds of thousands more had been bought and sold within individual states.

Americans continue to misunderstand how slavery worked and how vast was its reach – even as the histories of race and slavery are central to ongoing public conversations.

Indifference to suffering

Enslaved people were bought and sold within the boundaries of what is now the United States dating back to the Colonial era. But the domestic slave trade accelerated dramatically in the decades after 1808.

That year, Congress outlawed the importation of enslaved people from overseas, and it did so at a moment when demand for enslaved laborers was booming in expanding cotton and sugar plantation regions of the lower South.

Growing numbers of professional slave traders stepped forward to satisfy that demand. They purchased enslaved people primarily in upper South states like Maryland and Virginia, where a declining tobacco economy left many slaveholders with a surplus of laborers. Traders then forced those enslaved people to migrate hundreds of miles over land and by ship, selling them in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and other states where traders hoped to turn a profit.

The domestic slave trade was a brutal and violent business. Enslaved people lived in constant fear that they or their loved ones would be sold.

William Anderson, who was enslaved in Virginia, remembered seeing “hundreds of slaves pass by for the Southern market, chained and handcuffed together.” Years after he fled the South, Anderson wrote of “wives taken from husbands and husbands from wives, never to see each other again – small and large children separated from their parents,” and he never forgot the sounds of their sorrow. “O, I have seen them and heard them howl like dogs or wolves,” he recalled, “when being under the painful obligation of parting to meet no more.”

Slave traders were largely indifferent to the suffering they caused. Asked in the 1830s whether he broke up slave families in the course of his operations, one trader admitted that he did so “very often,” because “his business is to purchase, and he must take such as are in the market.”

‘So wicked’

Domestic slave traders initially worked mostly out of taverns and hotels. Over time, an increasing number of them established offices, showrooms and prisons where they held enslaved people whom they intended to sell.

By the 1830s, the domestic slave trade was ubiquitous in the slave states. Newspaper advertisements blared “Cash for Negroes.” Storefront signs announced that “dealers in slaves” were inside. At ports and along roads, travelers reported seeing scores of enslaved people in chains.

Meanwhile, the money the trade generated and the credit that financed it circulated throughout the country and across the Atlantic, as even European banks and merchants looked to share in the gains.

The more visible the trade became, the more antislavery activists made it a core of their appeals. When abolitionist editor Benjamin Lundy, for example, asked white Americans in the 1820s how long they could look at the slave trade and “permit so disgraceful, so inhuman, and so wicked a practice to continue in our country, which has been emphatically termed THE HOME OF THE FREE,” he was one among a rising chorus.

But abolitionists made little headway. The domestic slave trade ended only when slavery ended in 1865.

Propaganda obscures history

Vital to the American economy, important to American politics and central to the experience of enslaved people, the domestic slave trade was an atrocity carried out on a massive scale. As British traveler Joseph Sturge noted, by the 1840s, the entire slaveholding portion of the United States could be characterized by division “into the ‘slave-breeding’ and ‘slave-consuming’ States.”

Yet popular historical knowledge of the domestic trade remains hazy, thanks largely to purposeful forgetting and to a propaganda campaign that began before the Civil War and continued long past its conclusion.

White Southerners made denial about the slave trade an important tenet in their defense of slavery. They claimed that slave sales were rare, that they detested the slave trade and that traders were outcasts disdained by respectable people.

Kentucky minister Nathan Lewis Rice’s assertion in 1845 that “the slave-trader is looked upon by decent men in the slave-holding States with disgust” was such a common sentiment that even white Northerners sometimes parroted it. Nehemiah Adams, for example, a Massachusetts resident who visited the South in 1854, came away from his time in the region believing that “Negro traders are the abhorrence of all flesh.”

Such claims were almost entirely lies. But downplaying the slave trade became a standard element of the racist mythology embedded in the defense of the Confederacy known as the Lost Cause, whose purveyors minimized slavery’s significance as they discounted its role in bringing about the Civil War.

And while the Confederacy may have lost on the battlefield, its supporters arguably triumphed in the cultural struggle to define the war and its meaning. Well into the 20th century, significant numbers of white Americans throughout the country accepted and embraced the notion that slavery had been relatively benign.

As they did so, the devastations of the domestic slave trade became buried beneath comforting fantasies of moonlight and magnolias evoked by movies like “Gone With the Wind.”

Recent years have seen monuments to the Confederacy coming down in cities and towns across the country. But the struggle over how Americans remember and talk about slavery, now perhaps more heated and controversial than ever, arguably remains stuck in terms that are legacies of the Lost Cause.

Slavery still conjures images of Southern farms and plantations. But the institution was grounded in the sales of nearly 2 million human beings in the domestic slave trade, the profits from which nurtured the economy of the entire country.

Until that history makes its way more deeply into our popular memory, it will be impossible to come to terms with slavery and its significance for the American past and present.

Historian: Republican culture war fight driven by need to hide a basic fact about American history

History News Network

July 19, 2021

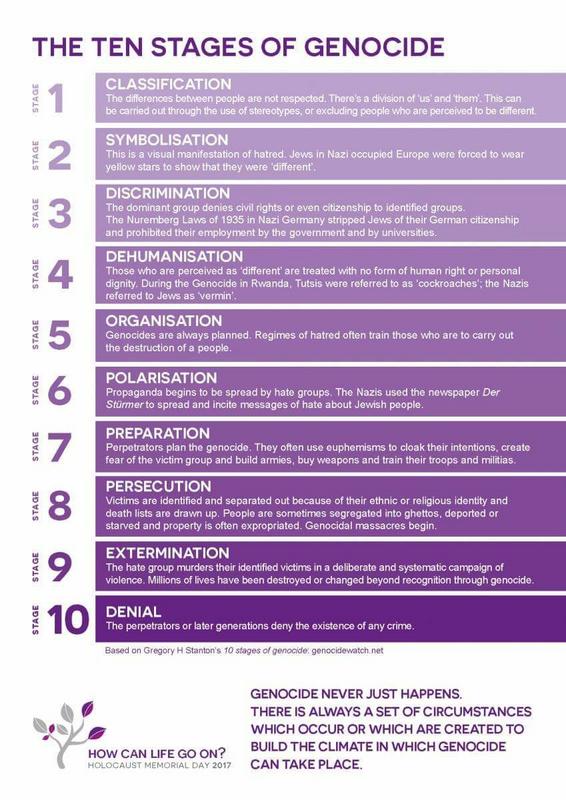

Critical Race Theory (CRT) has become a lightning rod for conservative ire at any discussion of racism, anti-racism, or the non-white history of America. Across the country, bills in Republican-controlled legislatures have attempted to prevent the teaching of CRT, even though most of those against CRT struggle to define the term. CRT actually began as a legal theory which held simply that systemic racism was consciously created, and therefore, must be consciously dismantled. History reveals that the foundation of America, and of systemic racism, happened at the same time and from the same set of consciously created laws.

Around the 20th of August, 1619, the White Lion, an English ship sailing under a Dutch flag, docked off Old Point Comfort (near present-day Hampton), in the British colony of Virginia, to barter approximately 20 Africans for much needed food and supplies. The facts of the White Lion's arrival in Virginia, and her human cargo, are generally not in dispute. Whether those first Africans arriving in America were taken by colonists as slaves or as indentured servants is still debated. But by the end of the 17th century, a system of chattel slavery was in place in colonial America. How America got from uncertainly about the status of Africans, to certainty that they were slaves, is a transition that highlights the origins of systemic racism.

Three arguments have been put forth about whether the first Africans arriving in the colonies were treated as indentured servants or as slaves. One says that European racism predisposed American colonists to treat these Africans as slaves. Anthony and Isabella, for example, two Africans aboard the White Lion, were acquired by Captain William Tucker and listed at the bottom of his 1624/25 muster (census) entry, just above his real property, but below white indentured servants and native Americans.

A second argument counters that racism was not, at first, the decisive factor but that the availability of free labor was. "Before the invention of the Negro or the white man or the words and concepts to describe them," historian Lerone Bennett wrote, "the Colonial population consisted largely of a great mass of white and black [and native] bondsmen, who occupied roughly the same economic category and were treated with equal contempt by the lords of the plantations and legislatures."

In this view, slavery was not born of racism, but racism was born of slavery. Early colonial laws had no provisions distinguishing African from European servants, until those laws began to change toward the middle of the 17th century, when Africans became subject to more brutal treatment than any other group. Proponents of this second argument point to cases like Elizabeth Key in 1656, or Phillip Corven in 1675, Black servants who sued in different court cases against their white masters for keeping them past the end of their indentures. Both Key and Corven won. If slavery was the law, Key and Corven would have had no standing in court much less any hope of prevailing.

Still, a third group stakes out slightly different ground. Separate Africans into two groups: the first generation that arrived before the middle of the 17th century, and those that arrived after. For the first generations of Africans, English and Dutch colonists had the concept of indefinite, but not inheritable, bondage. For those who came after, colonists applied the concept of lifetime, inheritable bondage. Here, the 1640 case of John Punch, a Black man caught with two other white servants attempting to run away, is often cited. As punishment, all the men received thirty lashes but the white servants had only one-year added to their indentures, while John Punch was ordered to serve his master "for the time of his natural life." For this reason, many consider John Punch the first real slave in America. Or was he the last Black indentured servant?

Clearly these cases show the ambiguity, or "loopholes," of the system separating servitude from slavery in early America. What is also clear is that one by one these loopholes were closed through conscious intent of colonial legislatures. In this reduction of ambiguity over the status of Africans, the closure of loopholes between servitude and slavery, are the roots of systemic racism.

Maryland enacted a first-of-its-kind law in 1664, specifically tying being Black to being a slave. "[A]ll Negroes or other slaves already within the Province And all Negroes and other slaves to be hereafter imported into the Province shall serve Durante Vita." Durante Vita is a Latin phrase meaning for the duration of one's life.

Another loophole concerned the status of children. Colonial American law was initially derived from English common law, where the status of child (whether bound or free) followed the status of the father. But adherence to English common law posed problems in colonial America, such as revealed in the 1630 case of Hugh Davis, a white man sentencing to whipping "for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a negro..." Whipping proved no deterrent for such interracial unions between a free European and a bound African. If English common law was followed, then the child of such a liaison would be free. So, in the years following Davis' whipping the legislatures in Maryland and Virginia enacted statutes that the status of the child, whether slave or free, followed that of the mother.

But closing this loophole assumes that only the sexual exploits of European men needed containing. The famous, and well-documented case of Irish milkmaid, Molly Welsh, who worked off her indentures in Maryland, shows the reverse actually happened as well. Welsh purchased a slaved named Banna Ka, whom she eventually freed, then married. They had a girl named Mary, who was free. Mary married a runaway slaved named Thomas, and they had a boy named Benjamin, who was also free. And Benjamin Banneker, a clockmaker, astronomer, mathematician, and surveyor, became an important figure in African American history, having authored a letter to Thomas Jefferson lamenting the lofty ideals of liberty and equality contained in the nation's founding documents were not extended to all citizens regardless of color.

Closing the religious exemption was another way in which colonial legislatures sought to separate Blacks from whites, and force slavery only on people of African descent. One of the reasons Elizabeth Key prevailed in court was that she asserted she could not be held in slavery as a Christian. In fact, there was a widespread belief in early America that Christians holding other Christians in slavery went against core biblical teachings.

Most first generation Africans in colonial America came from the Angola-Congo region of West Africa, first taken there by the Portuguese. Christianity was well-known, and practiced by Africans in these regions as early as the 15th century. So, many Africans destined for slavery, or indentured servitude in America, were already baptized, or were christened by priests aboard Portuguese slave trading vessels.

Colonial legislatures got busy. Maryland updated the 1664 law, cited above, with a 1671 statute that specifically carved out a religious exception for people of African descent. Regardless of whether they had become Christian, or received the sacrament of baptism, they would "hereafter be adjudged, reputed, deemed, and taken to be and remain in servitude and bondage" forever. Acts like this led to a tortured, convoluted American Christianity, developed to support slavery, and this legacy of racism within American Christianity continues to this day.

Apprehension of runaway servants and slaves was still another area in which colonial legislatures targeted people of color for differential, oppressive treatment. While granting masters the right to send a posse after runaways, a 1672 Virginia statute called "An act for the apprehension and suppression of runawayes, negroes and slaves," granted immunity to any white person who killed or wounded a runaway person of color while in pursuit of them. It read:

"Be it enacted by the governour, councell and burgesses of this grand assembly, and by the authority thereof, that if any negroe, molatto, Indian slave, or servant for life, runaway and shalbe persued by warrant or hue and crye, it shall and may be lawfull for any person who shall endeavour to take them, upon the resistance of such negroe, mollatto, Indian slave, or servant for life, to kill or wound him or them soe resisting."

Acts like this became the basis for slave patrols, and for the police forces that arose from them. Today, we still deal with the consequences of "qualified immunity," stemming from ideas like these enacted in 1672, which shield police from prosecution in cases of violence and brutality, especially against people of color.

Protection of southern rights even found its way into the Constitution. The Second Amendment protects the right of militias (a polite term for "slave patrols") to organize and bear arms. The Fugitive Slave Clause (never repealed) guaranteed southern slaveholders that their slaves apprehended in the North would be returned. Even the Interstate Commerce Clause allowed Southerners traveling North with their slaves assurances those slaves would not automatically become free by setting foot in states that outlawed slavery.

Though enacted centuries ago, the laws cited above are representative of the many laws that came to define American jurisprudence, and have at their core, the repression and oppression of Black Americans, and other people of color. This is why Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, writing for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857, handed down a 7-2 verdict in the Dred Scott case, with the words that Blacks had "no rights which the white man was bound to respect." This is why critical race theory states that systemic racism was consciously created, as these laws and their enforcement show they were.

But this is also why Republican legislators and their supporters lump anything and everything having to do with diversity, equity, and inclusion into the box of critical race theory, then try to keep it out of schools and public institutions. They're afraid of Americans being told the truth: that the foundation of America, and of systemic racism, happened at the same time and from the same consciously created laws. In this way, these individuals are actually living proof of the validity of critical race theory, because they seek to consciously enact laws today which perpetuate the racial inequality established by laws enacted hundreds of years ago.

Around the 20th of August, 1619, the White Lion, an English ship sailing under a Dutch flag, docked off Old Point Comfort (near present-day Hampton), in the British colony of Virginia, to barter approximately 20 Africans for much needed food and supplies. The facts of the White Lion's arrival in Virginia, and her human cargo, are generally not in dispute. Whether those first Africans arriving in America were taken by colonists as slaves or as indentured servants is still debated. But by the end of the 17th century, a system of chattel slavery was in place in colonial America. How America got from uncertainly about the status of Africans, to certainty that they were slaves, is a transition that highlights the origins of systemic racism.

Three arguments have been put forth about whether the first Africans arriving in the colonies were treated as indentured servants or as slaves. One says that European racism predisposed American colonists to treat these Africans as slaves. Anthony and Isabella, for example, two Africans aboard the White Lion, were acquired by Captain William Tucker and listed at the bottom of his 1624/25 muster (census) entry, just above his real property, but below white indentured servants and native Americans.

A second argument counters that racism was not, at first, the decisive factor but that the availability of free labor was. "Before the invention of the Negro or the white man or the words and concepts to describe them," historian Lerone Bennett wrote, "the Colonial population consisted largely of a great mass of white and black [and native] bondsmen, who occupied roughly the same economic category and were treated with equal contempt by the lords of the plantations and legislatures."

In this view, slavery was not born of racism, but racism was born of slavery. Early colonial laws had no provisions distinguishing African from European servants, until those laws began to change toward the middle of the 17th century, when Africans became subject to more brutal treatment than any other group. Proponents of this second argument point to cases like Elizabeth Key in 1656, or Phillip Corven in 1675, Black servants who sued in different court cases against their white masters for keeping them past the end of their indentures. Both Key and Corven won. If slavery was the law, Key and Corven would have had no standing in court much less any hope of prevailing.

Still, a third group stakes out slightly different ground. Separate Africans into two groups: the first generation that arrived before the middle of the 17th century, and those that arrived after. For the first generations of Africans, English and Dutch colonists had the concept of indefinite, but not inheritable, bondage. For those who came after, colonists applied the concept of lifetime, inheritable bondage. Here, the 1640 case of John Punch, a Black man caught with two other white servants attempting to run away, is often cited. As punishment, all the men received thirty lashes but the white servants had only one-year added to their indentures, while John Punch was ordered to serve his master "for the time of his natural life." For this reason, many consider John Punch the first real slave in America. Or was he the last Black indentured servant?

Clearly these cases show the ambiguity, or "loopholes," of the system separating servitude from slavery in early America. What is also clear is that one by one these loopholes were closed through conscious intent of colonial legislatures. In this reduction of ambiguity over the status of Africans, the closure of loopholes between servitude and slavery, are the roots of systemic racism.

Maryland enacted a first-of-its-kind law in 1664, specifically tying being Black to being a slave. "[A]ll Negroes or other slaves already within the Province And all Negroes and other slaves to be hereafter imported into the Province shall serve Durante Vita." Durante Vita is a Latin phrase meaning for the duration of one's life.

Another loophole concerned the status of children. Colonial American law was initially derived from English common law, where the status of child (whether bound or free) followed the status of the father. But adherence to English common law posed problems in colonial America, such as revealed in the 1630 case of Hugh Davis, a white man sentencing to whipping "for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a negro..." Whipping proved no deterrent for such interracial unions between a free European and a bound African. If English common law was followed, then the child of such a liaison would be free. So, in the years following Davis' whipping the legislatures in Maryland and Virginia enacted statutes that the status of the child, whether slave or free, followed that of the mother.

But closing this loophole assumes that only the sexual exploits of European men needed containing. The famous, and well-documented case of Irish milkmaid, Molly Welsh, who worked off her indentures in Maryland, shows the reverse actually happened as well. Welsh purchased a slaved named Banna Ka, whom she eventually freed, then married. They had a girl named Mary, who was free. Mary married a runaway slaved named Thomas, and they had a boy named Benjamin, who was also free. And Benjamin Banneker, a clockmaker, astronomer, mathematician, and surveyor, became an important figure in African American history, having authored a letter to Thomas Jefferson lamenting the lofty ideals of liberty and equality contained in the nation's founding documents were not extended to all citizens regardless of color.

Closing the religious exemption was another way in which colonial legislatures sought to separate Blacks from whites, and force slavery only on people of African descent. One of the reasons Elizabeth Key prevailed in court was that she asserted she could not be held in slavery as a Christian. In fact, there was a widespread belief in early America that Christians holding other Christians in slavery went against core biblical teachings.

Most first generation Africans in colonial America came from the Angola-Congo region of West Africa, first taken there by the Portuguese. Christianity was well-known, and practiced by Africans in these regions as early as the 15th century. So, many Africans destined for slavery, or indentured servitude in America, were already baptized, or were christened by priests aboard Portuguese slave trading vessels.

Colonial legislatures got busy. Maryland updated the 1664 law, cited above, with a 1671 statute that specifically carved out a religious exception for people of African descent. Regardless of whether they had become Christian, or received the sacrament of baptism, they would "hereafter be adjudged, reputed, deemed, and taken to be and remain in servitude and bondage" forever. Acts like this led to a tortured, convoluted American Christianity, developed to support slavery, and this legacy of racism within American Christianity continues to this day.

Apprehension of runaway servants and slaves was still another area in which colonial legislatures targeted people of color for differential, oppressive treatment. While granting masters the right to send a posse after runaways, a 1672 Virginia statute called "An act for the apprehension and suppression of runawayes, negroes and slaves," granted immunity to any white person who killed or wounded a runaway person of color while in pursuit of them. It read:

"Be it enacted by the governour, councell and burgesses of this grand assembly, and by the authority thereof, that if any negroe, molatto, Indian slave, or servant for life, runaway and shalbe persued by warrant or hue and crye, it shall and may be lawfull for any person who shall endeavour to take them, upon the resistance of such negroe, mollatto, Indian slave, or servant for life, to kill or wound him or them soe resisting."

Acts like this became the basis for slave patrols, and for the police forces that arose from them. Today, we still deal with the consequences of "qualified immunity," stemming from ideas like these enacted in 1672, which shield police from prosecution in cases of violence and brutality, especially against people of color.

Protection of southern rights even found its way into the Constitution. The Second Amendment protects the right of militias (a polite term for "slave patrols") to organize and bear arms. The Fugitive Slave Clause (never repealed) guaranteed southern slaveholders that their slaves apprehended in the North would be returned. Even the Interstate Commerce Clause allowed Southerners traveling North with their slaves assurances those slaves would not automatically become free by setting foot in states that outlawed slavery.

Though enacted centuries ago, the laws cited above are representative of the many laws that came to define American jurisprudence, and have at their core, the repression and oppression of Black Americans, and other people of color. This is why Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, writing for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857, handed down a 7-2 verdict in the Dred Scott case, with the words that Blacks had "no rights which the white man was bound to respect." This is why critical race theory states that systemic racism was consciously created, as these laws and their enforcement show they were.

But this is also why Republican legislators and their supporters lump anything and everything having to do with diversity, equity, and inclusion into the box of critical race theory, then try to keep it out of schools and public institutions. They're afraid of Americans being told the truth: that the foundation of America, and of systemic racism, happened at the same time and from the same consciously created laws. In this way, these individuals are actually living proof of the validity of critical race theory, because they seek to consciously enact laws today which perpetuate the racial inequality established by laws enacted hundreds of years ago.

White Supremacy Was on Trial at Washington and Lee University. It Won.

BY BRANDON HASBROUCK - SLATE

JUNE 07, 20215:06 PM

After the end of the Civil War, Robert E. Lee, the general who commanded the army of the Confederacy, was never tried, convicted, or sentenced for any crimes—not treason, not murder, not torture. Instead, he became president of Washington College, where he attracted students molded in his image, inspired by his lost cause, and motivated to maintain racial hierarchy. Under Lee’s leadership, his students would, among other things, form a KKK chapter and harass and assault Black school children. The board of trustees of Washington College honored this legacy when it decided to rename its institution Washington and Lee University.

Lee is the embodiment of white supremacy—he lived a life, as I previously argued, committed to racial subjugation and terror. He fought to enslave Black people—so the Confederate States of America could continue to profit on Black labor and Black pain while creating an antidemocratic state founded upon white supremacy. For this reason many stakeholders asked the current board of trustees of Washington and Lee University, where I am an assistant professor of law at the law school, to remove Lee as a namesake. After significant and critical national attention, Lee was finally put on trial at the place where his body is buried. Not guilty, the board of trustees announced on Friday. The vote was not even close—a supermajority of trustees (22 out of 28 trustees or 78 percent) voted to retain Lee as a namesake. That vote, however, did more. It signaled that Washington and Lee University will continue to shine as a beacon of racism, hate, and privilege.

In response to the board’s decision, the university’s president released a statement. He declared that Lee’s name does not define the university or its stakeholders; rather “we define it.” But we cannot engage in historical revisionism to redefine Lee’s name, nor should we. The board announced its commitment to “repudiating racism, racial injustice, and Confederate nostalgia.” But we cannot hope to make consequential change until we accept the truth of what Lee’s name means.

The jury at Washington and Lee harkens back to Jim Crow juries—white, male, privileged, and rigged. The jury, composed of 28 trustee members, was mostly white (25 trustees) and mostly male (23 trustees). Many of the witnesses supporting Lee were white, as were many of the big donors who threatened to withhold contributions if Lee’s name was removed. The outcome was never in doubt.

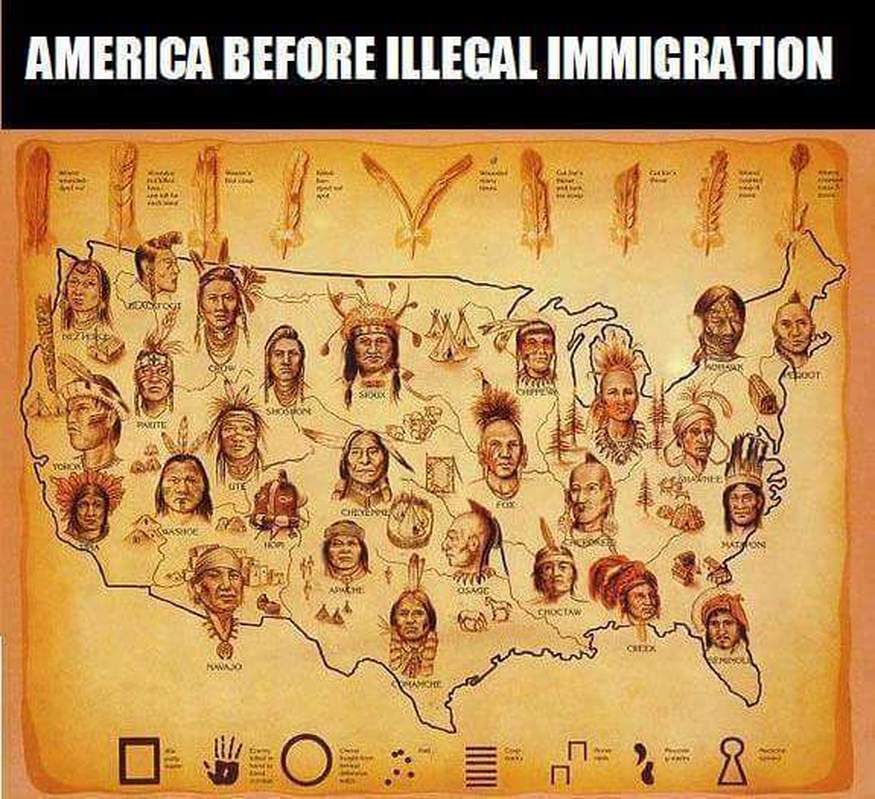

White supremacy has been put on trial before throughout our history. The outcomes in those trials was also predictable. The “Indian Removal Act” ensured white officials could never be found guilty of stealing Native land and committing genocide on the Trail of Tears. White insurrectionists in Wilmington, North Carolina murdered Black residents, destroyed Black-owned businesses and then ousted Wilmington’s anti-segregation, pro-equal rights government to insulate themselves against accountability. The United States Supreme Court sanctioned Japanese internment during World War II. An all-white, all male jury found Emmett Till’s murderers not guilty after 67 minutes of deliberation. Los Angeles cops were acquitted of bludgeoning Rodney King after the jury watched the tape more than 30 times.

When our racial ghosts are on trial, we know the outcome. When truth and justice are on trial, we know the outcome. When our country is asked to reject a revisionist tissue of historical lies, we known the outcome. White supremacy wins. White supremacy remains adaptable, persistent, violent, and nearly undefeated.

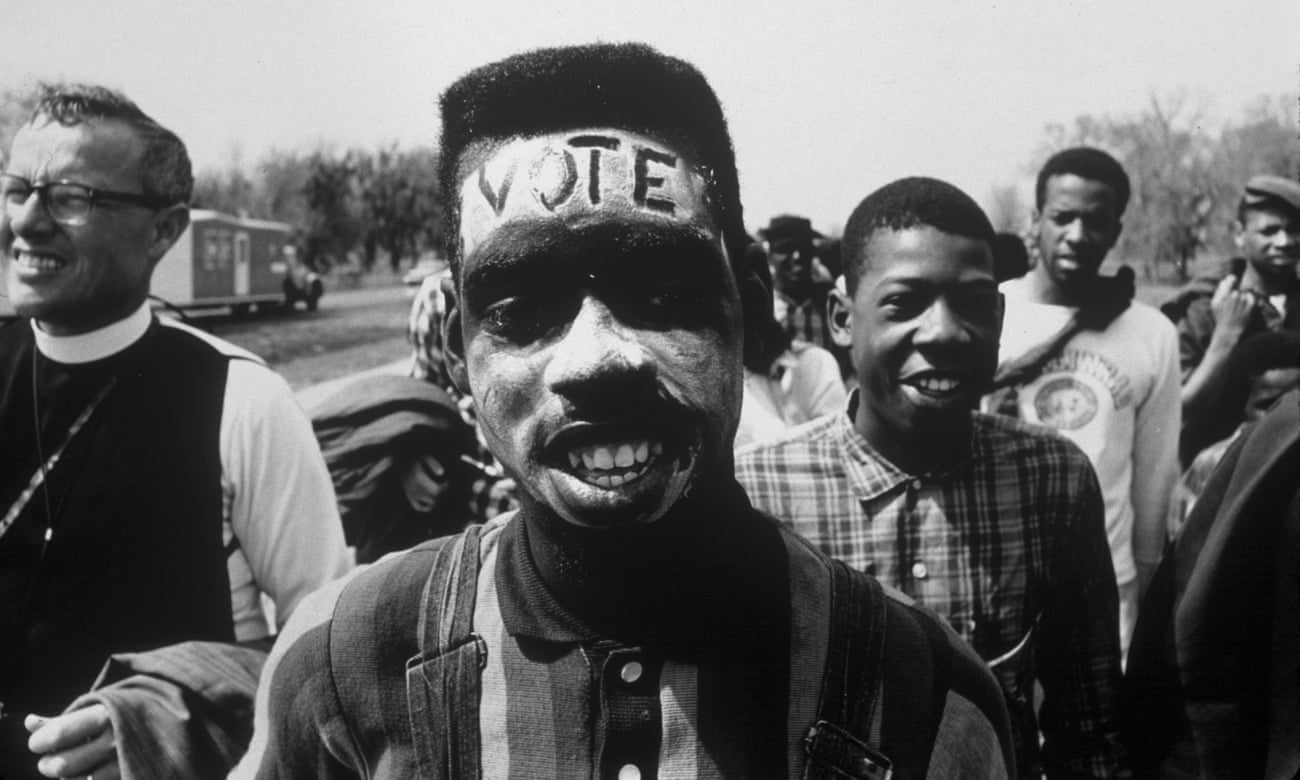

It inspires an insurrection. It introduces 389 restrictive voting right bills in 48 states over the past six months. It forbids schools to give a true accounting of our history—a history of racial violence, from the Trail of Tears, to Black Wall Street, to extrajudicial killings including those of Emmet Till, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor. It allows Washington and Lee University to keep Lee as a namesake because it is safer to benefit from white supremacy than to summon the courage to even appear antiracist.

Historical revisionism shelters white supremacy. It entrenches white supremacy. It emboldens white supremacy. We need truth and reconciliation in America. We must face our past head on and acknowledge it for what it was¾oppression and racial terror fueled by white supremacy. Only then can we start to reimagine our democratic institutions as more—more just, more fair, more equal. Only then will we build the capacity, the resolve, and the collective will to find white supremacy guilty.

Lee is the embodiment of white supremacy—he lived a life, as I previously argued, committed to racial subjugation and terror. He fought to enslave Black people—so the Confederate States of America could continue to profit on Black labor and Black pain while creating an antidemocratic state founded upon white supremacy. For this reason many stakeholders asked the current board of trustees of Washington and Lee University, where I am an assistant professor of law at the law school, to remove Lee as a namesake. After significant and critical national attention, Lee was finally put on trial at the place where his body is buried. Not guilty, the board of trustees announced on Friday. The vote was not even close—a supermajority of trustees (22 out of 28 trustees or 78 percent) voted to retain Lee as a namesake. That vote, however, did more. It signaled that Washington and Lee University will continue to shine as a beacon of racism, hate, and privilege.

In response to the board’s decision, the university’s president released a statement. He declared that Lee’s name does not define the university or its stakeholders; rather “we define it.” But we cannot engage in historical revisionism to redefine Lee’s name, nor should we. The board announced its commitment to “repudiating racism, racial injustice, and Confederate nostalgia.” But we cannot hope to make consequential change until we accept the truth of what Lee’s name means.

The jury at Washington and Lee harkens back to Jim Crow juries—white, male, privileged, and rigged. The jury, composed of 28 trustee members, was mostly white (25 trustees) and mostly male (23 trustees). Many of the witnesses supporting Lee were white, as were many of the big donors who threatened to withhold contributions if Lee’s name was removed. The outcome was never in doubt.

White supremacy has been put on trial before throughout our history. The outcomes in those trials was also predictable. The “Indian Removal Act” ensured white officials could never be found guilty of stealing Native land and committing genocide on the Trail of Tears. White insurrectionists in Wilmington, North Carolina murdered Black residents, destroyed Black-owned businesses and then ousted Wilmington’s anti-segregation, pro-equal rights government to insulate themselves against accountability. The United States Supreme Court sanctioned Japanese internment during World War II. An all-white, all male jury found Emmett Till’s murderers not guilty after 67 minutes of deliberation. Los Angeles cops were acquitted of bludgeoning Rodney King after the jury watched the tape more than 30 times.

When our racial ghosts are on trial, we know the outcome. When truth and justice are on trial, we know the outcome. When our country is asked to reject a revisionist tissue of historical lies, we known the outcome. White supremacy wins. White supremacy remains adaptable, persistent, violent, and nearly undefeated.

It inspires an insurrection. It introduces 389 restrictive voting right bills in 48 states over the past six months. It forbids schools to give a true accounting of our history—a history of racial violence, from the Trail of Tears, to Black Wall Street, to extrajudicial killings including those of Emmet Till, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor. It allows Washington and Lee University to keep Lee as a namesake because it is safer to benefit from white supremacy than to summon the courage to even appear antiracist.

Historical revisionism shelters white supremacy. It entrenches white supremacy. It emboldens white supremacy. We need truth and reconciliation in America. We must face our past head on and acknowledge it for what it was¾oppression and racial terror fueled by white supremacy. Only then can we start to reimagine our democratic institutions as more—more just, more fair, more equal. Only then will we build the capacity, the resolve, and the collective will to find white supremacy guilty.

America's History of Slavery Began Long Before Jamestown

The arrival of the first captives to the Jamestown Colony, in 1619, is often seen as the beginning of slavery in America—but enslaved Africans arrived in North America as early as the 1500s.

CRYSTAL PONTI - HISTORY.COM

UPDATED:AUG 26, 2019ORIGINAL:AUG 14, 2019

In late August 1619, the White Lion, an English privateer commanded by John Jope, sailed into Point Comfort and dropped anchor in the James River. Virginia colonist John Rolfe documented the arrival of the ship and “20 and odd” Africans on board. His journal entry is immortalized in textbooks, with 1619 often used as a reference point for teaching the origins of slavery in America. But the history, it seems, is far more complicated than a single date.

It is believed the first Africans brought to the colony of Virginia, 400 years ago this month, were Kimbundu-speaking peoples from the kingdom of Ndongo, located in part of present-day Angola. Slave traders forced the captives to march several hundred miles to the coast to board the San Juan Bautista, one of at least 36 transatlantic Portuguese and Spanish slave ships.

The ship embarked with about 350 Africans on board, but hunger and disease took a swift toll. En route, about 150 captives died. Then, when the San Juan Bautista approached what is now Veracruz, Mexico in the summer of 1619, it encountered two ships, the White Lion and another English privateer, the Treasurer. The crews stormed the vulnerable slave ship and seized 50 to 60 of the remaining Africans. After, the pair sailed for Virginia.

As noted by Rolfe, when the White Lion arrived in what is now present-day Hampton, Virginia, the Africans were offloaded and “bought for victuals.” Governor Sir George Yeardley and head merchant Abraham Piersey acquired the majority of the captives, most of whom were kept in Jamestown, America’s first permanent English settlement.

The arrival of these “20 and odd” Africans to England’s mainland American colonies in 1619 is now a focal point in history curricula. The date and their story have become symbolic of slavery’s roots, despite captive Africans likely being present in the Americas in the 1400s and as early as 1526 in the region that would become the United States.

Some experts, including Michael Guasco, a professor at Davidson College and author of Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World, caution about placing too much emphasis on the year 1619.

“To ignore what had been happening with relative frequency in the broader Atlantic world over the preceding 100 years or so understates the real brutality of the ongoing slave trade, of which the 1619 group were undoubtedly a part, and minimizes the significant African presence in the Atlantic world to that point,” Guasco explains. “People of African descent have been ‘here’ longer than the English colonies.”

Africans had a notable presence in the Americas before colonization

Prior to 1619, hundreds of thousands of Africans, both free and enslaved, aided the establishment and survival of colonies in the Americas and the New World. They also fought against European oppression, and, in some instances, hindered the systematic spread of colonization.

Christopher Columbus likely transported the first Africans to the Americas in the late 1490s on his expeditions to Hispaniola, now part of the Dominican Republic. Their exact status, whether free or enslaved, remains disputed. But the timeline fits with what we know of the origins of the slave trade.

European trade of enslaved Africans began in the 1400s. “The first example we have of Africans being taken against their will and put on board European ships would take the story back to 1441,” says Guasco, when the Portuguese captured 12 Africans in Cabo Branco—modern-day Mauritania in north Africa—and brought them to Portugal as enslaved peoples.

In the region that would become the United States, there were no enslaved Africans before the Spanish occupation of Florida in the early 16th century, according to Linda Heywood and John Thornton, professors at Boston University and co-authors of Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660.

“There were significant numbers who were brought in as early as 1526,” says Heywood. That year, some of these enslaved Africans became part of a Spanish expedition to establish an outpost in what is now South Carolina. They rebelled, preventing the Spanish from founding the colony.

The uprising didn’t stop the inflow of enslaved Africans to Spanish Florida. “We don’t know how many followed, but there was certainly a slave population around St. Augustine," says Heywood.

Africans also played a role in England's early colonization efforts. Enslaved Africans may have been on board Sir Francis Drake’s fleet when he arrived at Roanoke Island in 1586 and failed to establish the first permanent English settlement in America. He and his cousin, John Hawkins, made three voyages to Guinea and Sierra Leone and enslaved between 1,200 and 1,400 Africans.

Although not part of present-day America, Africans from the West Indies were also present in the English colony of Bermuda in 1616, where they provided expert knowledge of tobacco cultivation to the Virginia Company.

Focusing on the English colonies omits the global nature of slavery

From an Anglo-American perspective, 1619 is considered the beginning of slavery, just like Jamestown and Plymouth symbolize the beginnings of "America" from an English-speaking point of view. But divorcing the idea of North America's first enslaved people from the overall context of slavery in the Americas, especially when the U.S. was not formed for another 157 years, is not historically accurate.

“We would do well to remember that much of what played out in places like Virginia were the result of things that had already happened in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, Peru, Brazil and elsewhere,” says Guasco.

“The English took note of their fellow Europeans’ role in enslavement and the slave trade,” says Mark Summers, a public historian at Jamestown Rediscovery. In the context of the broader Atlantic world, the colony and institution of slavery developed from a chain of events involving multiple actors.

Still, U.S. school curricula tend to ignore much of what happened in the Atlantic prior to the Jamestown settlement and also the colonial projects of other countries that became part of America, such as Dutch New York, Swedish Delaware and French-Spanish Louisiana and Florida. “There is both an Anglo-centrism and east coast bias to much of traditional American history,” says Summers.

While Heywood and Thornton acknowledge that 1619 remains a key date for slavery in America, they also argue that focusing too much on the first enslaved people at Jamestown can distort our understanding of history. “It does so by failing to understand that the development of slavery was a gradual process, and that laws other than English laws applied,” says Thornton.

In 1619, slavery, as codified by law, did not yet exist in Virginia or elsewhere in places that would later become the United States.

But any question about the status of Black people in the colonies—free, enslaved or indentured servants—was made clear with the passage of the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, a series of laws that stripped away legal rights and legalized the barbaric and dehumanizing nature of slavery.

As Guasco puts it, “The Spanish, Portuguese and English were co-conspirators in what we would now consider a crime against humanity.”

It is believed the first Africans brought to the colony of Virginia, 400 years ago this month, were Kimbundu-speaking peoples from the kingdom of Ndongo, located in part of present-day Angola. Slave traders forced the captives to march several hundred miles to the coast to board the San Juan Bautista, one of at least 36 transatlantic Portuguese and Spanish slave ships.

The ship embarked with about 350 Africans on board, but hunger and disease took a swift toll. En route, about 150 captives died. Then, when the San Juan Bautista approached what is now Veracruz, Mexico in the summer of 1619, it encountered two ships, the White Lion and another English privateer, the Treasurer. The crews stormed the vulnerable slave ship and seized 50 to 60 of the remaining Africans. After, the pair sailed for Virginia.

As noted by Rolfe, when the White Lion arrived in what is now present-day Hampton, Virginia, the Africans were offloaded and “bought for victuals.” Governor Sir George Yeardley and head merchant Abraham Piersey acquired the majority of the captives, most of whom were kept in Jamestown, America’s first permanent English settlement.

The arrival of these “20 and odd” Africans to England’s mainland American colonies in 1619 is now a focal point in history curricula. The date and their story have become symbolic of slavery’s roots, despite captive Africans likely being present in the Americas in the 1400s and as early as 1526 in the region that would become the United States.

Some experts, including Michael Guasco, a professor at Davidson College and author of Slaves and Englishmen: Human Bondage in the Early Modern Atlantic World, caution about placing too much emphasis on the year 1619.

“To ignore what had been happening with relative frequency in the broader Atlantic world over the preceding 100 years or so understates the real brutality of the ongoing slave trade, of which the 1619 group were undoubtedly a part, and minimizes the significant African presence in the Atlantic world to that point,” Guasco explains. “People of African descent have been ‘here’ longer than the English colonies.”

Africans had a notable presence in the Americas before colonization

Prior to 1619, hundreds of thousands of Africans, both free and enslaved, aided the establishment and survival of colonies in the Americas and the New World. They also fought against European oppression, and, in some instances, hindered the systematic spread of colonization.

Christopher Columbus likely transported the first Africans to the Americas in the late 1490s on his expeditions to Hispaniola, now part of the Dominican Republic. Their exact status, whether free or enslaved, remains disputed. But the timeline fits with what we know of the origins of the slave trade.

European trade of enslaved Africans began in the 1400s. “The first example we have of Africans being taken against their will and put on board European ships would take the story back to 1441,” says Guasco, when the Portuguese captured 12 Africans in Cabo Branco—modern-day Mauritania in north Africa—and brought them to Portugal as enslaved peoples.

In the region that would become the United States, there were no enslaved Africans before the Spanish occupation of Florida in the early 16th century, according to Linda Heywood and John Thornton, professors at Boston University and co-authors of Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585-1660.

“There were significant numbers who were brought in as early as 1526,” says Heywood. That year, some of these enslaved Africans became part of a Spanish expedition to establish an outpost in what is now South Carolina. They rebelled, preventing the Spanish from founding the colony.

The uprising didn’t stop the inflow of enslaved Africans to Spanish Florida. “We don’t know how many followed, but there was certainly a slave population around St. Augustine," says Heywood.

Africans also played a role in England's early colonization efforts. Enslaved Africans may have been on board Sir Francis Drake’s fleet when he arrived at Roanoke Island in 1586 and failed to establish the first permanent English settlement in America. He and his cousin, John Hawkins, made three voyages to Guinea and Sierra Leone and enslaved between 1,200 and 1,400 Africans.

Although not part of present-day America, Africans from the West Indies were also present in the English colony of Bermuda in 1616, where they provided expert knowledge of tobacco cultivation to the Virginia Company.

Focusing on the English colonies omits the global nature of slavery

From an Anglo-American perspective, 1619 is considered the beginning of slavery, just like Jamestown and Plymouth symbolize the beginnings of "America" from an English-speaking point of view. But divorcing the idea of North America's first enslaved people from the overall context of slavery in the Americas, especially when the U.S. was not formed for another 157 years, is not historically accurate.

“We would do well to remember that much of what played out in places like Virginia were the result of things that had already happened in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, Peru, Brazil and elsewhere,” says Guasco.

“The English took note of their fellow Europeans’ role in enslavement and the slave trade,” says Mark Summers, a public historian at Jamestown Rediscovery. In the context of the broader Atlantic world, the colony and institution of slavery developed from a chain of events involving multiple actors.

Still, U.S. school curricula tend to ignore much of what happened in the Atlantic prior to the Jamestown settlement and also the colonial projects of other countries that became part of America, such as Dutch New York, Swedish Delaware and French-Spanish Louisiana and Florida. “There is both an Anglo-centrism and east coast bias to much of traditional American history,” says Summers.

While Heywood and Thornton acknowledge that 1619 remains a key date for slavery in America, they also argue that focusing too much on the first enslaved people at Jamestown can distort our understanding of history. “It does so by failing to understand that the development of slavery was a gradual process, and that laws other than English laws applied,” says Thornton.

In 1619, slavery, as codified by law, did not yet exist in Virginia or elsewhere in places that would later become the United States.

But any question about the status of Black people in the colonies—free, enslaved or indentured servants—was made clear with the passage of the Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, a series of laws that stripped away legal rights and legalized the barbaric and dehumanizing nature of slavery.

As Guasco puts it, “The Spanish, Portuguese and English were co-conspirators in what we would now consider a crime against humanity.”

There was a time reparations were actually paid out – just not to formerly enslaved people

THE CONVERSATION

February 26, 2021 8.26am EST

The cost of slavery and its legacy of systemic racism to generations of Black Americans has been clear over the past year – seen in both the racial disparities of the pandemic and widespread protests over police brutality.

Yet whenever calls for reparations are made – as they are again now – opponents counter that it would be unfair to saddle a debt on those not personally responsible. In the words of then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, speaking on Juneteenth – the day Black Americans celebrate as marking emancipation – in 2019, “I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea.”

As a professor of public policy who has studied reparations, I acknowledge that the figures involved are large – I conservatively estimate the losses from unpaid wages and lost inheritances to Black descendants of the enslaved at around US$20 trillion in 2021 dollars.

But what often gets forgotten by those who oppose reparations is that payouts for slavery have been made before – numerous times, in fact. And few at the time complained that it was unfair to saddle generations of people with a debt for which they were not personally responsible.

There is an important caveat in these cases of reparations though: The payments went to former slave owners and their descendants, not the enslaved or their legal heirs.

Extorting Haiti

A prominent example is the so-called “Haitian Independence Debt” that saddled revolutionary Haiti with reparation payments to former slave owners in France.

Haiti declared independence from France in 1804, but the former colonial power refused to acknowledge the fact for another 20 years. Then in 1825, King Charles X decreed that he would recognize independence, but at a cost. The price tag would be 150 million francs – more than 10 years of the Haitian government’s entire revenue. The money, the French said, was needed to compensate former slave owners for the loss of what was deemed their property.