TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

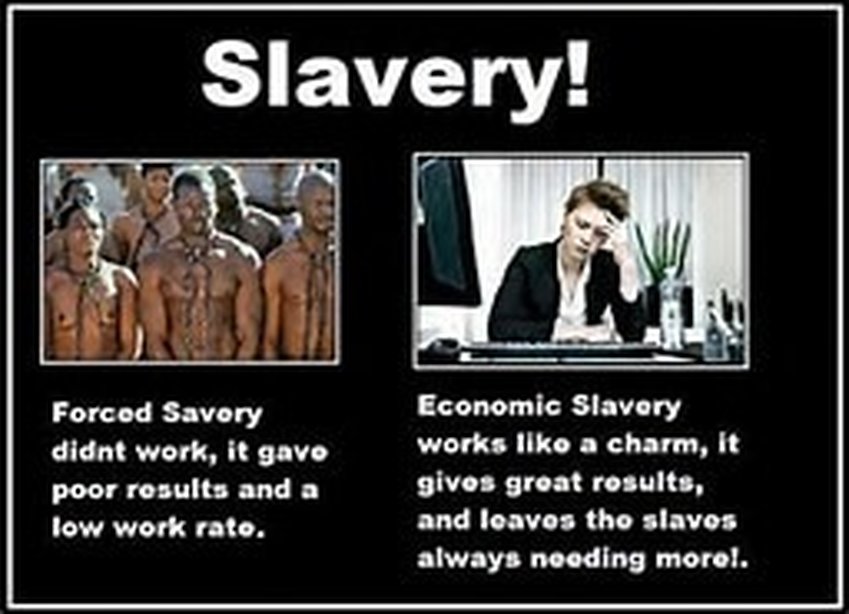

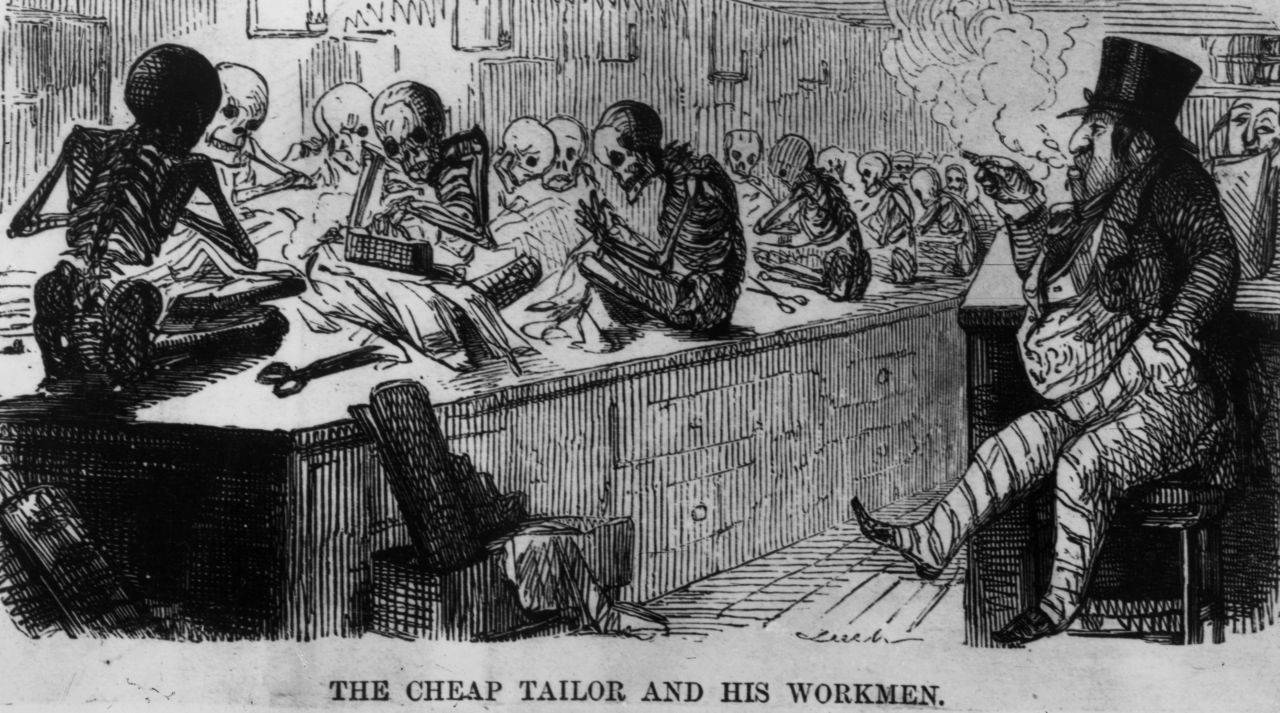

Slavery 21st Century

You thought it was over, think again

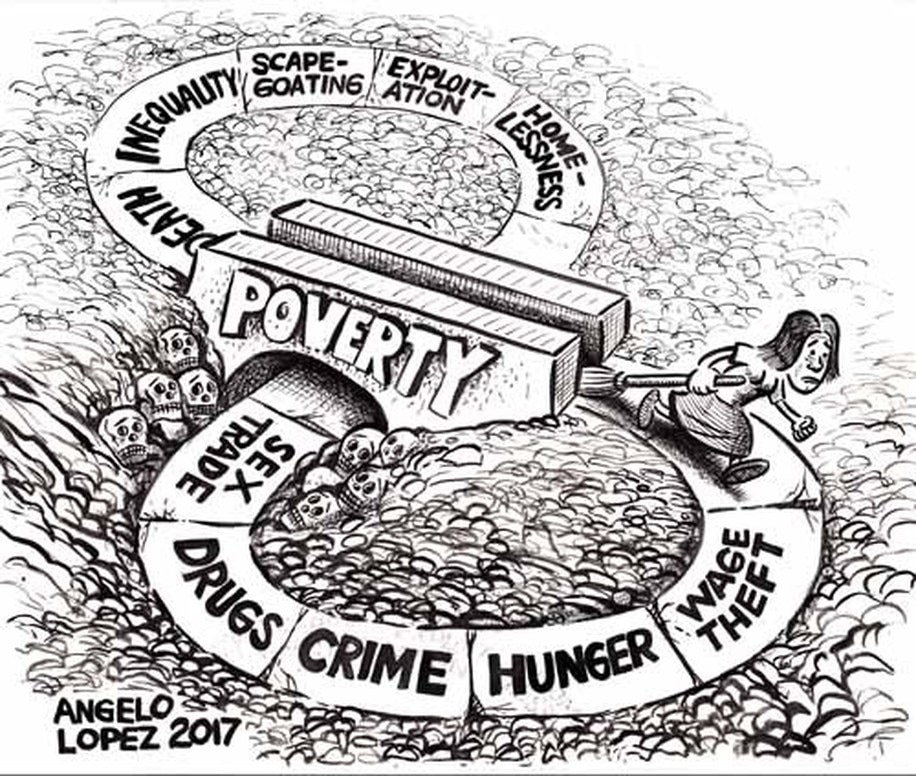

the corporations of today are just remodeled slave plantations of the past

june 2024

Slavery did not end it was merely outsourced,

reconfigured, and made politically correct

The Global Slavery Index

published on Thursday by Walk Free Foundation, describes modern slavery as a complex and often hidden crime that crosses borders, sectors and jurisdictions. The US number, the study estimates, is almost one hundredth of the estimated 40.3 million global total number of people it defines as being enslaved.

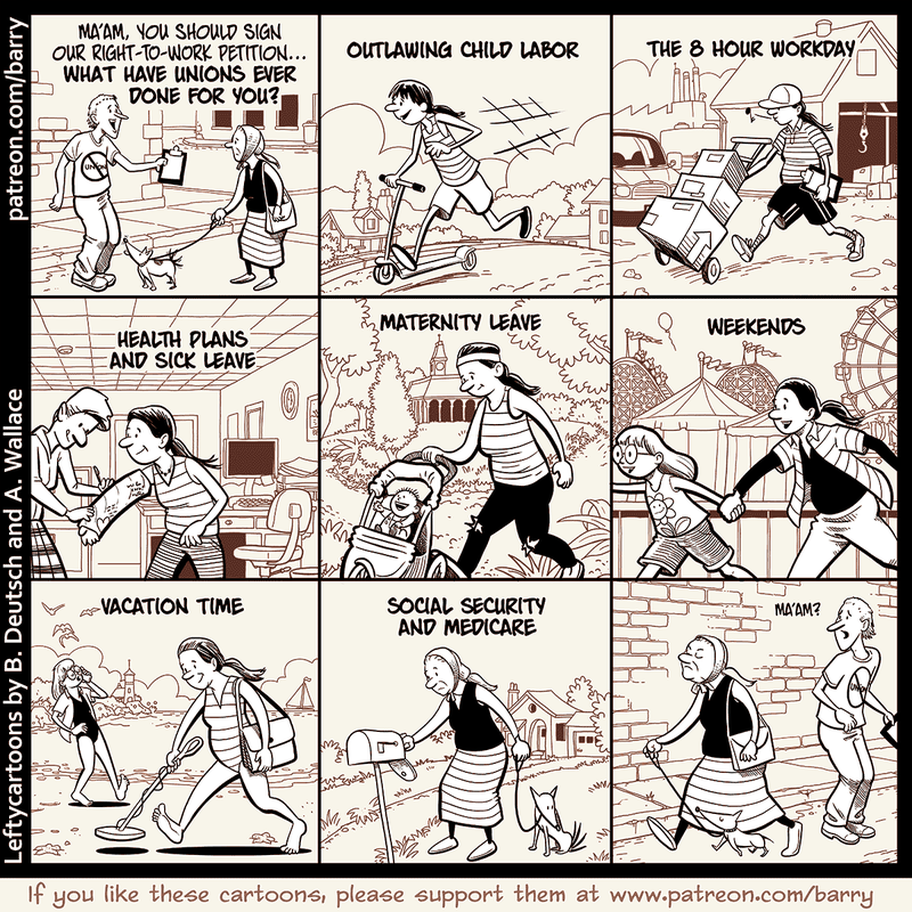

labor history - recommended reading

*THE SILK STRIKE OF 1913

*AMERICAN LABOR VIOLENCE: ITS CAUSES, CHARACTER, AND OUTCOME

headlines and issues

*THE MOST COMMON ESSENTIAL JOBS IN THE US DON’T PAY A LIVING WAGE

THE ECONOMY IS IMPROVING, BUT INEQUALITY IS TEARING THE US APART. DEMOCRATS IGNORE WORKING-CLASS PAIN AT THEIR PERIL.(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ADVOCATES SUE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT FOR FAILING TO BAN IMPORTS OF COCOA HARVESTED BY CHILDREN(ARTICLE BELOW)

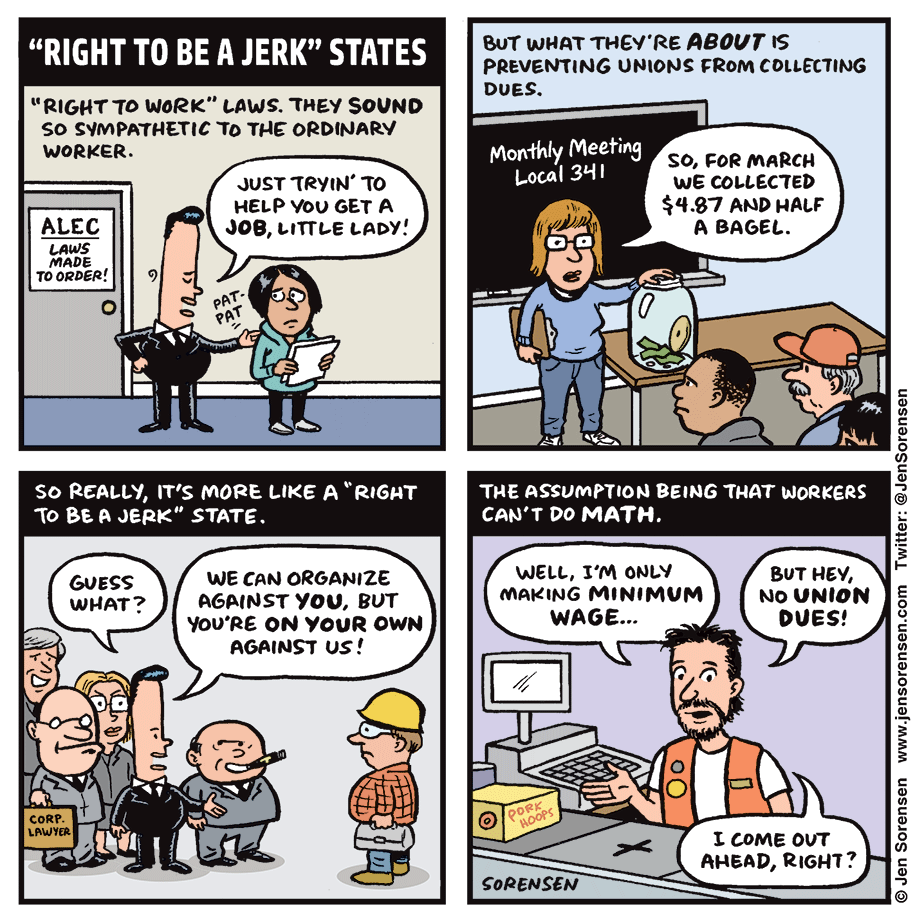

*Workers Fighting Union-Busting May Have a New Legal Tool at Their Disposal

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*GEICO IS TRYING TO CRUSH WORKERS’ ATTEMPTS TO FORM AN INDEPENDENT UNION

(ARTICLE BELOW)

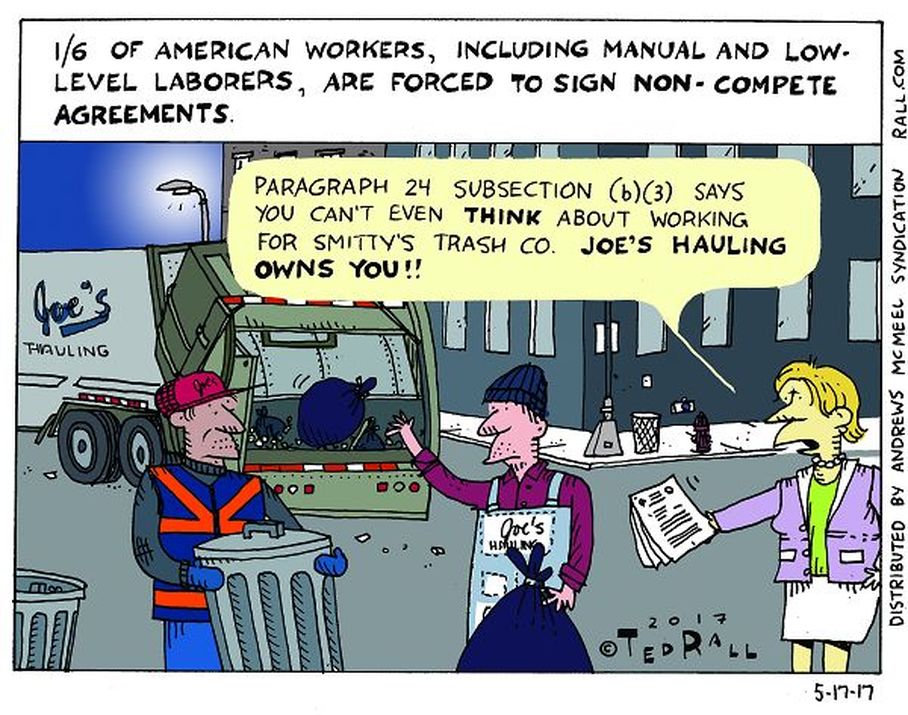

*MORE US EMPLOYERS ARE TRAPPING WORKERS IN A NEW FORM OF INDENTURED SERVITUDE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

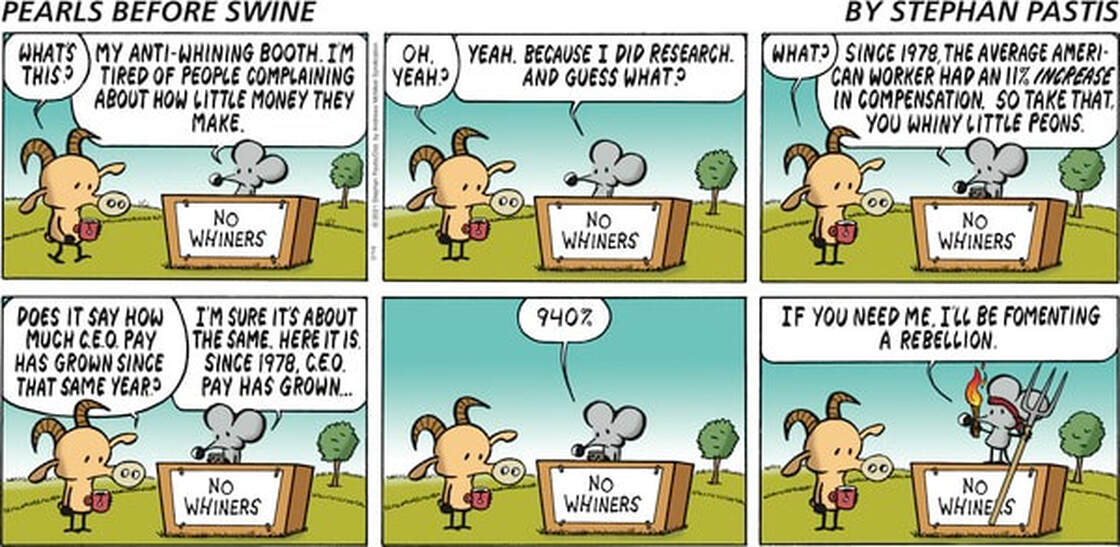

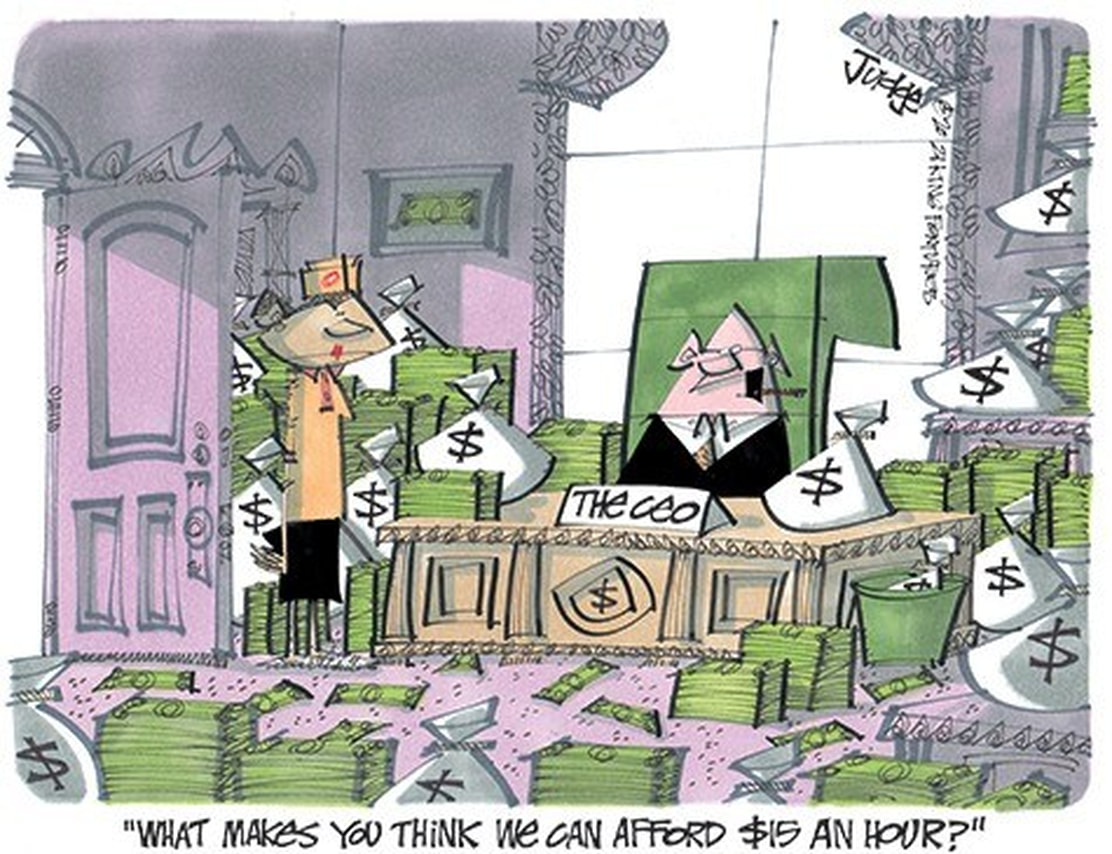

*CEO WHO GOT $940 MILLION RICHER IN PANDEMIC IS BEHIND STARBUCKS UNION-BUSTING

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*STARBUCKS CREATING ‘CULTURE OF FEAR’ AS IT FIRES DOZENS INVOLVED IN UNION EFFORTS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Judge Orders Starbucks to Reinstate 7 Fired Pro-Union Workers in Memphis

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*In a Year, Amazon Disciplined Workers 13,000 Times at Now-Unionized Warehouse

(ARTICLE BELOW)

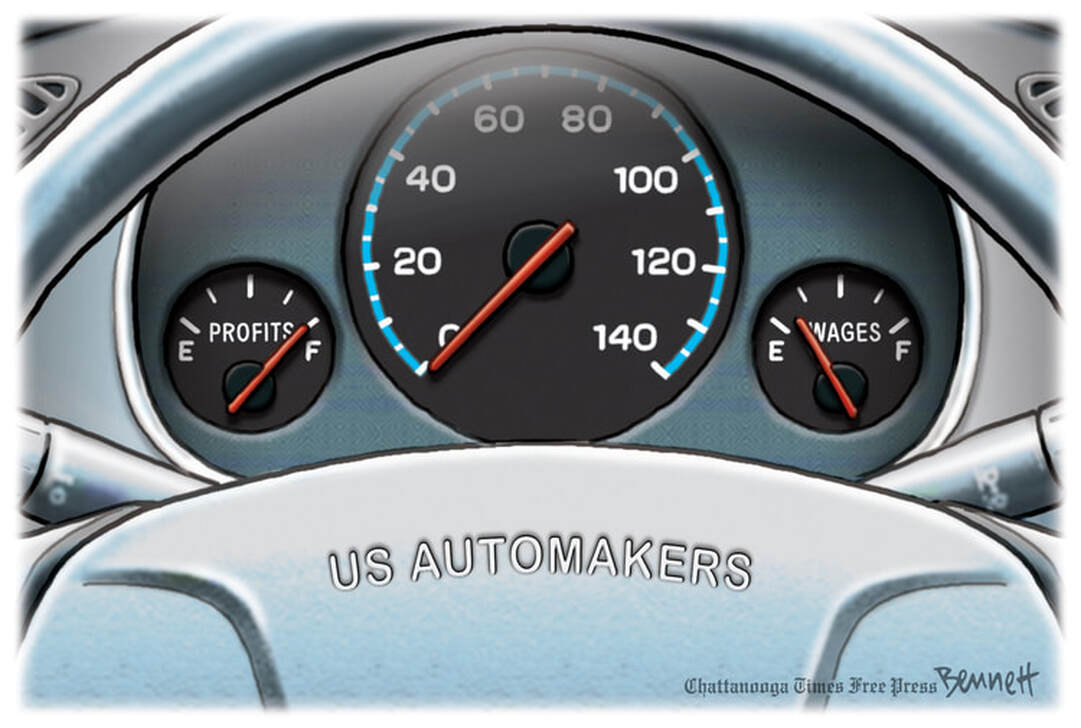

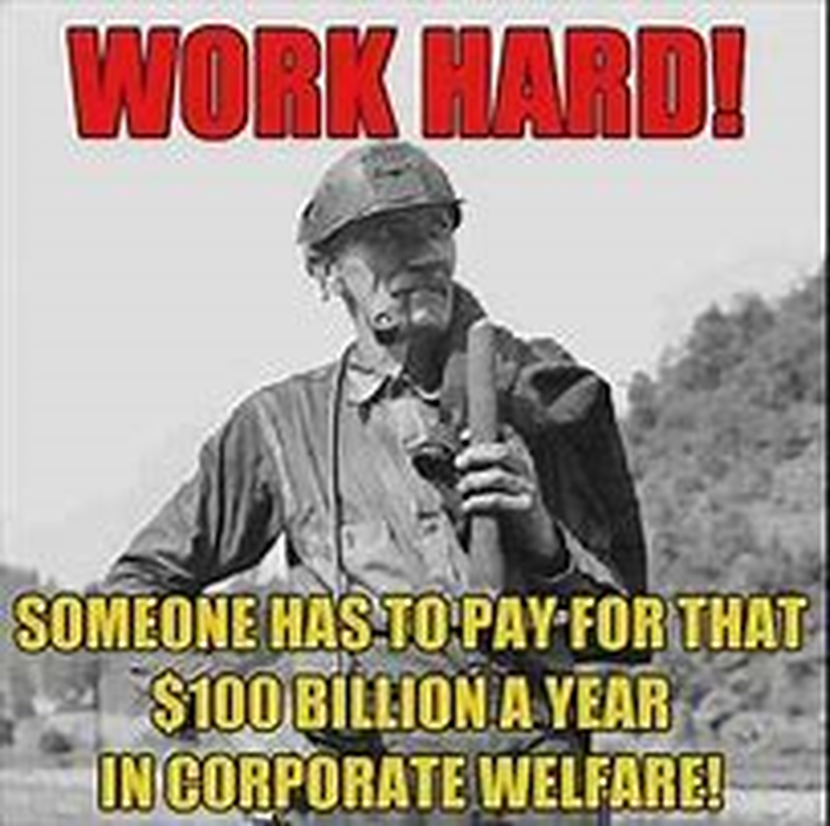

*TOP US CEOS MADE 254 TIMES MORE THAN MEDIAN WORKERS IN 2021, STUDY SHOWS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*STARBUCKS ANTI-UNION PUSH BACKFIRES

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Starbucks Asks Labor Board to Stop Ongoing Union Election in Mesa, Arizona

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WANT TO BE A CRIMINAL IN AMERICA? STEALING BILLIONS IS YOUR BEST BET TO GO SCOT-FREE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*‘THIS HAS BEEN HAPPENING FOR A LONG TIME’: MODERN-DAY SLAVERY UNCOVERED IN SOUTH GEORGIA(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Anti-masker abuse, subpar healthcare, and a 5 cent raise: CVS workers say enough is enough(ARTICLE BELOW)

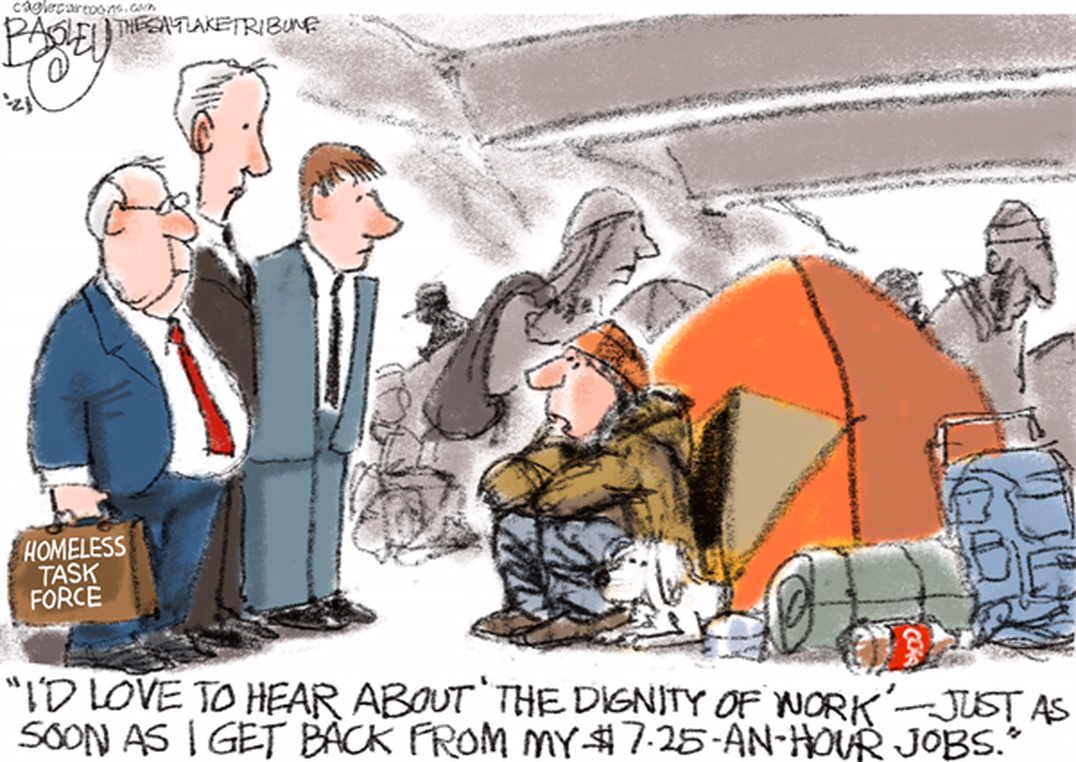

*AMERICAN CEOS MAKE 351 TIMES MORE THAN WORKERS. IN 1965 IT WAS 15 TO ONE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

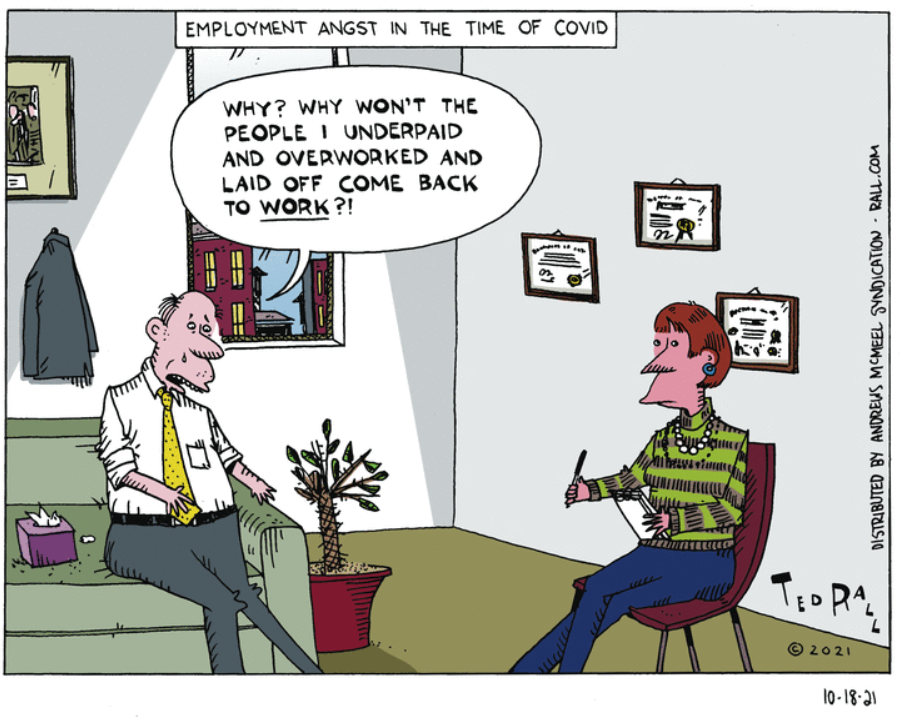

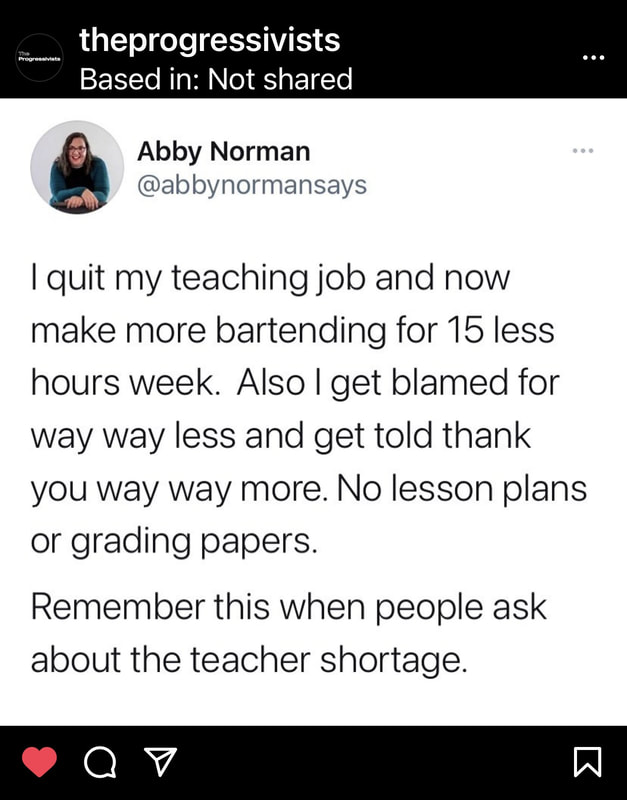

*More Workers Are Saying That Minimum-Wage Jobs Just Aren’t Worth It Anymore

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*AMAZON PRESSURED ALABAMA WORKERS TO VOTE AGAINST UNIONIZATION, LABOR BOARD FINDS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A Supreme Court ruling that's right out of the 19th century

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CEOS MADE 299 TIMES THE SALARY OF WHAT THE MEDIAN EMPLOYEE RECEIVED: ANALYSIS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*New York's 'essential' food delivery workers demand rights

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Overworked, underpaid: workers rail against hotel chains’ cost-cutting

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ROBERT REICH: BLAME CHIPOTLE, NOT WORKERS, FOR THE PRICE OF YOUR BURRITO

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Only 3 Percent of Jobs on Tennessee Government Website Pay Over $20,000

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE U.S. IS COMPLICIT IN THE GLOBAL WAR ON WORKERS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Striking coalminers in Alabama energize support across the south

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Kroger, Blasted for Ending Hazard Pay, Gave CEO $22 Million

(ARTICLE BELOW)

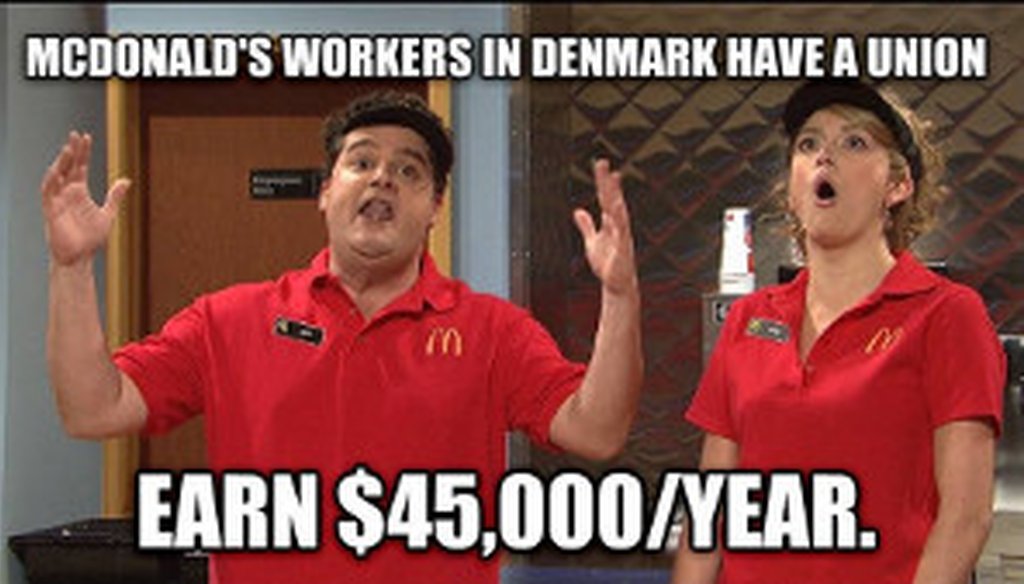

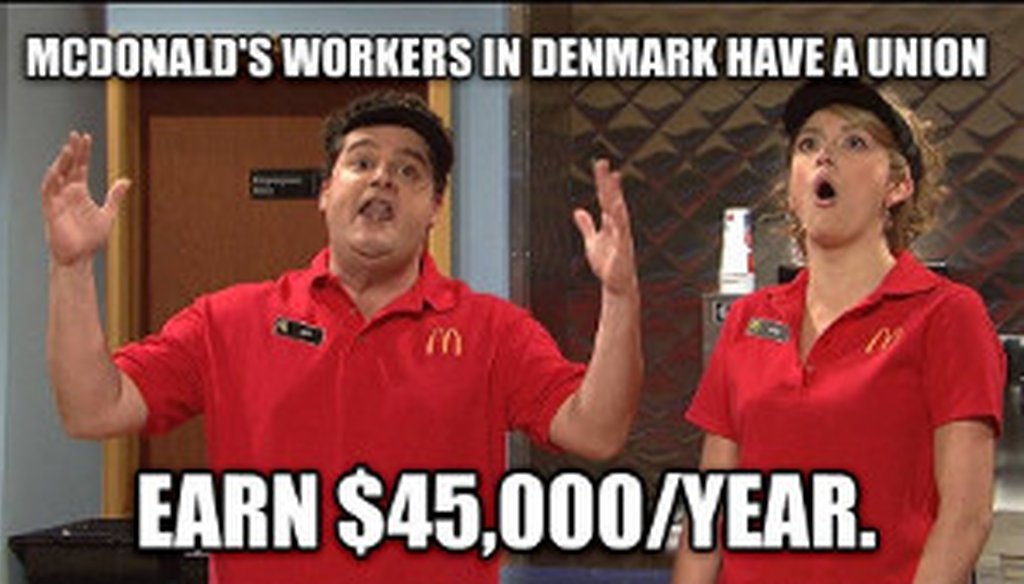

*McDonald's Raises Pay for U.S. Restaurant Workers

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE US RESTAURANT INDUSTRY IS LACKING IN WAGES, NOT WORKERS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*How Our Postal Service Helped Deliver Win To Amazon In Defeat Of Union

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CALIFORNIA WORKERS PAID AS LITTLE AS $2 AN HOUR -- AND IT'S TOTALLY LEGAL

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*MEDIAN WORKER MAKES $3,250 LESS PER YEAR THAN IN 1979 DUE TO DECLINE IN UNIONS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*At a Major Education Company, Freelancers Must Now Pay a Fee In Order to Get Paid

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*AMAZON RETALIATED AGAINST CHICAGO WORKERS FOLLOWING SPRING COVID-19 PROTESTS, NLRB FINDS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*14-HOUR DAYS AND NO BATHROOM BREAKS: AMAZON'S OVERWORKED DELIVERY DRIVERS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

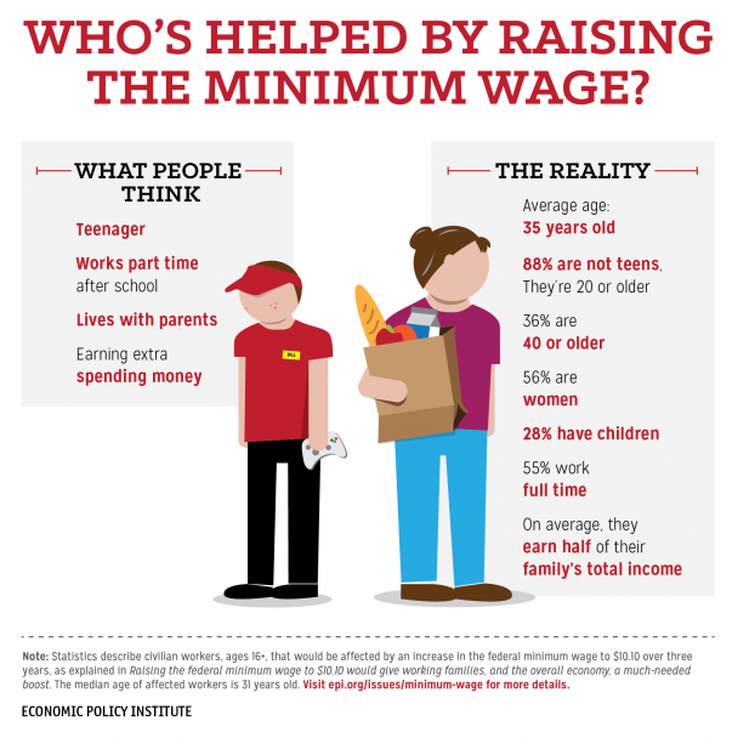

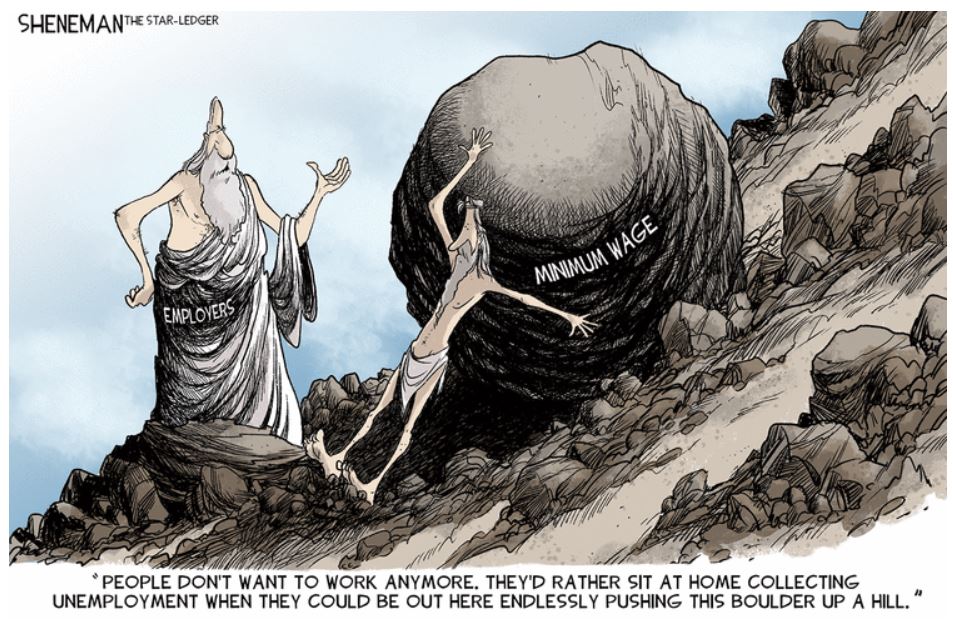

*HIKING THE MINIMUM WAGE TO $15 IS KEY — BUT IT’S HARDLY A LIVING WAGE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WHY IT'S TIME TO MAKE LARGE CORPORATIONS PAY LIVING WAGES

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE 1.5 MILLION CHILD SLAVES BEHIND YOUR CHOCOLATE BAR

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*How corporations try to divide and exploit America's workers

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*GOVERNMENT STUDY SHOWS TAXPAYERS ARE SUBSIDIZING “STARVATION WAGES” AT MCDONALD'S, WALMART(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Robert Reich: Here are the 5 biggest corporate lies about unions

(ARTICLE BELOW)

funnies(at the end)Whole Foods staff to protest working conditions as coronavirus cases rise

slavery 21st century!!!

The Most Common Essential Jobs in the US Don’t Pay a Living Wage

The economy is improving, but inequality is tearing the US apart. Democrats ignore working-class pain at their peril.

By Mike Ludwig , TRUTHOUT

Published June 20, 2024

The most common jobs in the United States are home health care aide, retail salesperson and fast-food and counter worker, which are all tied for first place on a long list of professions tracked by the government, according to analysis of federal data by The Washington Post. From caring for the elderly to serving the lunch rush, people who work these jobs are bedrocks of the everyday economy.

However, the 2023 median salaries listed for the top three most common jobs — and many others — do not offer a living wage in any state across the country. Ranging from about $29,500 for home care aides to $33,600 for fast-food servers, the median salaries offered by the top three most common jobs are at least $11,000 short of what is needed to make ends meet in states with the cheapest cost of living. California is out of the question.

“Median salary tells you that exactly half [of the workers] are being paid less, and half are being paid more,” said Elise Gould, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), in an interview.

Median salaries are not much better for public school teachers, restaurant servers, janitors, bus drivers, warehouse stockers and order fillers, and many essential workers who were hailed as heroes during pandemic lockdowns. With wages and the cost of living quicky becoming major campaign issues ahead of the November elections, President Joe Biden is trailing Donald Trump in the polls and hemorrhaging support from voters without college degrees, a large group that includes many Black and Latino voters as well as union members that Democrats depend on.

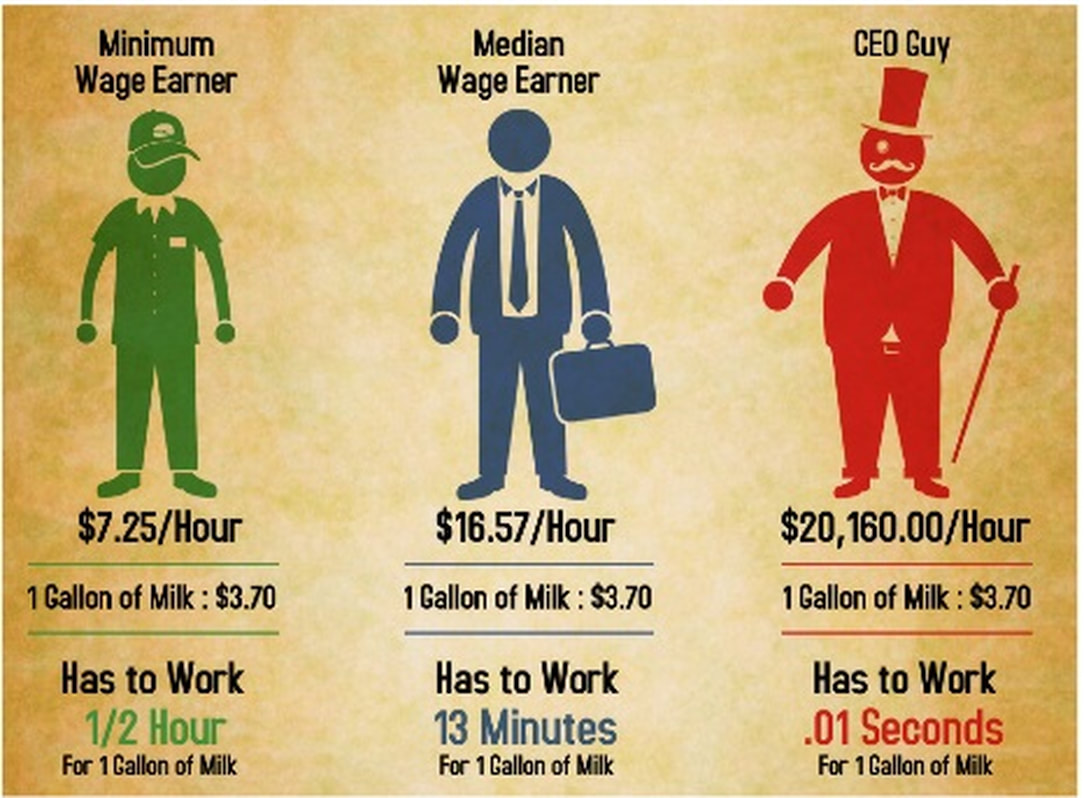

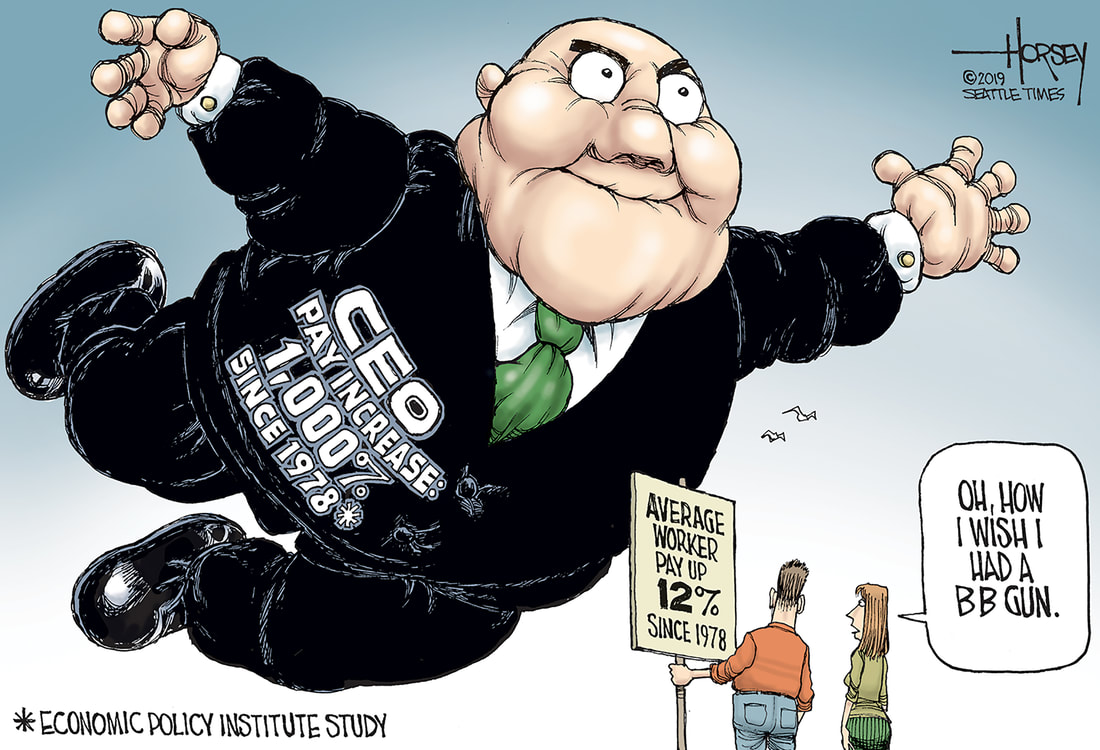

Meanwhile, executive compensation is ballooning at the highest rate in 14 years. CEO pay at S&P 500 countries increased by nearly 13 percent in 2023, while the average worker saw only a 4.1 percent increase in pay. Economic optimists point to a booming stock market and low unemployment, but the inequality gap between the wealthiest earners and everyone else is increasing nearly three times faster than overall wage growth.

The data reflects trends going back decades. In 1965, CEOs were paid 21 times more than the typical worker, but in 2022 CEOs made 344 times more, according to EPI.

The most common job after the top three is “general and operations manager,” which includes bosses and supervisors of lower-wage workers. Managers earn a median salary of $101,000, about three times the median salary offered to employees in fast food or retail. Working toward a manager position at a burger chain or corporate store is an age-old trope, but how do workers support their families in the meantime when the cost of living is out of reach?

Despite a much-touted economic recovery, about half the country is still living paycheck to paycheck, and deep income inequality is increasingly the throughline connecting so many woes and resentments. From the polarization and anti-immigrant animus exploited by Trump and the global far right, to skyrocketing housing prices and mass homelessness, the affordability crisis is taking center stage in the public consciousness.

Jo Risper, a senior electoral organizer at Right to the City, a national alliance of tenants’ unions and racial justice groups, said wage increases haven’t caught up with the cost of housing in cities across the country. Risper said roughly half of all tenants spend at least 30 percent of their income on rent, and of those, about 50 percent are spending 50 percent of their income just to stay in their homes.

“Minimum wage hasn’t gone up in 15 years, but from 2018 to 2021 the average rent was raised up to 30 percent,” Risper said in an interview.

After years of pushing neoliberal policies that benefited elites, Risper said Biden and other establishment politicians ignore this working-class pain at their own peril.

Tenants who rent their homes represent 26 percent of the electorate in five key battleground states coveted by Trump and Biden, including Pennsylvania and Michigan. The majority are younger voters under the age of 35. Along with health care and wages, the cost of housing is a clear priority for tenants, with 82 percent believing their lives would improve if the issue were addressed by policy makers, according to a poll commissioned by Right to the City. However, 51 percent of these potential voters report that they do not hear politicians talking about the issue “much” or “at all.”

Swing state tenants tend to have a more favorable view of Biden than Trump, and 77 percent say they would vote for a candidate that supports rent stabilization, a position favored by some progressives. It’s enthusiasm for Biden and the Democrats that is lacking. According to the Center for Popular Democracy, only 58 percent of swing state renters have said they will “definitely” turn out November — a significant drop from the number who self-reported turning out in 2020.

Risper said Democratic candidates tend to focus their messaging and canvassing on homeowners rather than renters, even as their constituents face stagnating wages and steep rent hikes. With rent prices up 31 percent since 2019, corporate landlords see their profits soaring.

“They say we just need to build more housing, but in reality, for folks who are home health aides or fast-food workers, they can’t afford to buy a house,” Risper said. “They are losing their base, and this is a block of voters.”

Democrats boast about low unemployment numbers and record wage growth since the pandemic, but with millions of people struggling to pay make ends meet, Biden remains one of the most unpopular presidents in modern times. To understand why, Gould looks beyond Biden’s time in office.

Thanks to state-level minimum wage hikes and a tight labor market, low paid and historical disadvantaged workers saw the fastest wage growth between 2019 and 2023, although wage growth has slowed as pay for managers increases. However, wages for jobs at the bottom of the pay scale remain insufficient to make ends meet, and the wealthiest earners keep taking bigger pieces of the pies off the top.

“Low- and moderate-wage workers typically have seen very little wage growth over the past 40 years, and that makes it harder and hard to make ends meet,” Gould said. “They were barely making ends meet before and they are still barely making ends meet today, and they are not able to get head because of the four decades up to about 2019.”

However, the 2023 median salaries listed for the top three most common jobs — and many others — do not offer a living wage in any state across the country. Ranging from about $29,500 for home care aides to $33,600 for fast-food servers, the median salaries offered by the top three most common jobs are at least $11,000 short of what is needed to make ends meet in states with the cheapest cost of living. California is out of the question.

“Median salary tells you that exactly half [of the workers] are being paid less, and half are being paid more,” said Elise Gould, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), in an interview.

Median salaries are not much better for public school teachers, restaurant servers, janitors, bus drivers, warehouse stockers and order fillers, and many essential workers who were hailed as heroes during pandemic lockdowns. With wages and the cost of living quicky becoming major campaign issues ahead of the November elections, President Joe Biden is trailing Donald Trump in the polls and hemorrhaging support from voters without college degrees, a large group that includes many Black and Latino voters as well as union members that Democrats depend on.

Meanwhile, executive compensation is ballooning at the highest rate in 14 years. CEO pay at S&P 500 countries increased by nearly 13 percent in 2023, while the average worker saw only a 4.1 percent increase in pay. Economic optimists point to a booming stock market and low unemployment, but the inequality gap between the wealthiest earners and everyone else is increasing nearly three times faster than overall wage growth.

The data reflects trends going back decades. In 1965, CEOs were paid 21 times more than the typical worker, but in 2022 CEOs made 344 times more, according to EPI.

The most common job after the top three is “general and operations manager,” which includes bosses and supervisors of lower-wage workers. Managers earn a median salary of $101,000, about three times the median salary offered to employees in fast food or retail. Working toward a manager position at a burger chain or corporate store is an age-old trope, but how do workers support their families in the meantime when the cost of living is out of reach?

Despite a much-touted economic recovery, about half the country is still living paycheck to paycheck, and deep income inequality is increasingly the throughline connecting so many woes and resentments. From the polarization and anti-immigrant animus exploited by Trump and the global far right, to skyrocketing housing prices and mass homelessness, the affordability crisis is taking center stage in the public consciousness.

Jo Risper, a senior electoral organizer at Right to the City, a national alliance of tenants’ unions and racial justice groups, said wage increases haven’t caught up with the cost of housing in cities across the country. Risper said roughly half of all tenants spend at least 30 percent of their income on rent, and of those, about 50 percent are spending 50 percent of their income just to stay in their homes.

“Minimum wage hasn’t gone up in 15 years, but from 2018 to 2021 the average rent was raised up to 30 percent,” Risper said in an interview.

After years of pushing neoliberal policies that benefited elites, Risper said Biden and other establishment politicians ignore this working-class pain at their own peril.

Tenants who rent their homes represent 26 percent of the electorate in five key battleground states coveted by Trump and Biden, including Pennsylvania and Michigan. The majority are younger voters under the age of 35. Along with health care and wages, the cost of housing is a clear priority for tenants, with 82 percent believing their lives would improve if the issue were addressed by policy makers, according to a poll commissioned by Right to the City. However, 51 percent of these potential voters report that they do not hear politicians talking about the issue “much” or “at all.”

Swing state tenants tend to have a more favorable view of Biden than Trump, and 77 percent say they would vote for a candidate that supports rent stabilization, a position favored by some progressives. It’s enthusiasm for Biden and the Democrats that is lacking. According to the Center for Popular Democracy, only 58 percent of swing state renters have said they will “definitely” turn out November — a significant drop from the number who self-reported turning out in 2020.

Risper said Democratic candidates tend to focus their messaging and canvassing on homeowners rather than renters, even as their constituents face stagnating wages and steep rent hikes. With rent prices up 31 percent since 2019, corporate landlords see their profits soaring.

“They say we just need to build more housing, but in reality, for folks who are home health aides or fast-food workers, they can’t afford to buy a house,” Risper said. “They are losing their base, and this is a block of voters.”

Democrats boast about low unemployment numbers and record wage growth since the pandemic, but with millions of people struggling to pay make ends meet, Biden remains one of the most unpopular presidents in modern times. To understand why, Gould looks beyond Biden’s time in office.

Thanks to state-level minimum wage hikes and a tight labor market, low paid and historical disadvantaged workers saw the fastest wage growth between 2019 and 2023, although wage growth has slowed as pay for managers increases. However, wages for jobs at the bottom of the pay scale remain insufficient to make ends meet, and the wealthiest earners keep taking bigger pieces of the pies off the top.

“Low- and moderate-wage workers typically have seen very little wage growth over the past 40 years, and that makes it harder and hard to make ends meet,” Gould said. “They were barely making ends meet before and they are still barely making ends meet today, and they are not able to get head because of the four decades up to about 2019.”

SLAVERY 21ST CENTURY!!!

Advocates sue federal government for failing to ban imports of cocoa harvested by children

Child welfare advocates have filed a federal lawsuit asking a judge to force the Biden administration to block imports of cocoa harvested by children in West Africa that ends up in America’s most popular chocolate desserts and candies

MARTHA MENDOZA Associated Press

August 15, 2023, 5:25 AM

WASHINGTON -- Child welfare advocates filed a federal lawsuit Tuesday asking a judge to force the Biden administration to block imports of cocoa harvested by children in West Africa that can end up in America's most popular chocolate desserts and candies.

The lawsuit, brought by International Rights Advocates, seeks to have the federal government enforce a 1930s era federal law that requires the government to ban products created by child labor from entering the U.S.

The nonprofit group says it filed the suit because Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Homeland Security have ignored extensive evidence documenting children cultivating cocoa destined for well-known U.S. candy makers, including Hershey, Mars, Nestle and Cargill.

The major chocolate companies pledged to end their reliance on child labor to harvest their cocoa by 2005. Now they say they will eliminate the worst forms of child labor in their supply chains by 2025.

“They will never stop until they are forced to," said Terry Collingsworth, International Rights Advocates' executive director. He added that the U.S. government has "the power to end this incredible abuse of African children by enforcing the law.”

Spokespeople for CBP declined to comment on the suit, which was filed in the U.S. Court of International Trade. When asked more generally about cocoa produced by child labor, the federal agency said it was “unable to disclose additional information or plans regarding forced labor enforcement activities due to protections of law enforcement sensitive and business confidential information.”

Cocoa cultivation by children in Cote d’Ivoire, also known as the Ivory Coast, as well as neighboring Ghana, is not a new phenomenon. Human rights leaders, academics, news organizations and even federal agencies have spent the last two decades exposing the plight of children working on cocoa plantations in the West African nations, which produce about 70% of the world's cocoa supply.

A 2019 study by the University of Chicago, commissioned by the U.S. government, found 790,000 children, some as young as 5, were working on Ivory Coast cocoa plantations. The situation was similar in neighboring Ghana, researchers found.

The U.S. government has long recognized that child labor is a major problem in the Ivory Coast. The Department of Labor reported in 2021 that “children in Côte d’Ivoire are subjected to the worst forms of child labor, including in the harvesting of cocoa and coffee.”

The State Department in a recent report said that agriculture companies in the Ivory Coast rely on child labor to produce a range of products, including cocoa. The department said this year that human traffickers “exploit Ivoirian boys and boys from West African countries, especially Burkina Faso, in forced labor in agriculture, especially cocoa production."

To try to force companies to abandon cocoa produced by child labor, International Rights Advocates has sued some of the world’s large chocolate companies over the use of child labor in harvesting cocoa beans. It lost a case before the Supreme Court in 2021. Several others are pending.

Pressured by lawmakers and advocates, major chocolate makers in 2001 agreed to stop purchasing cocoa produced by child labor. That goal, experts and industry officials say, has not been met.

“These companies kept saying, ‘We can’t trace it back.’ That’s BS," said former Sen. Tom Harkin, who led a push for legislation to reform the industry, but ended up agreeing to a protocol that allows corporations to regulate themselves. “They just won’t do it because it will cost them money.”

Harkin said Americans don’t realize the treats they hand their children originate with child abuse.

“It’s not just the chocolate you eat, it’s the chocolate syrup you put on your ice cream, the cocoa you drink, the chocolate chip cookies you bake," he said.

The World Cocoa Foundation, which represents major cocoa companies, said it is committed to “improving livelihoods of cocoa farmers and their communities.”

A Hershey spokesperson said the company “does not tolerate child labor within our supply chain.” Cargill, Nestle and Mars did not respond to requests for comment. Their websites all describe their work to end child labor in cocoa plantations.

Ivory Coast officials have said they are taking steps to eradicate child labor but blocking imports of the nation's cocoa would devastate the nation's economy.

“We don’t want to un-employ the whole country,” said Collingsworth, the labor advocate who brought Tuesday's lawsuit. “We just want children replaced by adults in cocoa plantations.”

Collingsworth was in the Ivory Coast investigating working conditions when he noticed children chopping through brush and harvesting cocoa. He pulled out a phone and took video and photographs of the boys and girls at work. He also stopped by a nearby processing facility and took a photos of burlap sacks with labels of U.S. companies.

International Rights Advocates decided to petition the CBP to block imports of the cocoa, filing a 24-page petition in 2020 asking the agency take such action. The petition contained what it said was photographic and other evidence detailing how the companies were violating the law.

Collingsworth said his group also provided CBP with interviews with children as young as 12 who said their wages were being withheld, and that they had been tricked by recruiters into working long hours on a false promise they would be given land of their own.

CBP failed to take any action on the petition, the lawsuit alleges.

The lawsuit, brought by International Rights Advocates, seeks to have the federal government enforce a 1930s era federal law that requires the government to ban products created by child labor from entering the U.S.

The nonprofit group says it filed the suit because Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Homeland Security have ignored extensive evidence documenting children cultivating cocoa destined for well-known U.S. candy makers, including Hershey, Mars, Nestle and Cargill.

The major chocolate companies pledged to end their reliance on child labor to harvest their cocoa by 2005. Now they say they will eliminate the worst forms of child labor in their supply chains by 2025.

“They will never stop until they are forced to," said Terry Collingsworth, International Rights Advocates' executive director. He added that the U.S. government has "the power to end this incredible abuse of African children by enforcing the law.”

Spokespeople for CBP declined to comment on the suit, which was filed in the U.S. Court of International Trade. When asked more generally about cocoa produced by child labor, the federal agency said it was “unable to disclose additional information or plans regarding forced labor enforcement activities due to protections of law enforcement sensitive and business confidential information.”

Cocoa cultivation by children in Cote d’Ivoire, also known as the Ivory Coast, as well as neighboring Ghana, is not a new phenomenon. Human rights leaders, academics, news organizations and even federal agencies have spent the last two decades exposing the plight of children working on cocoa plantations in the West African nations, which produce about 70% of the world's cocoa supply.

A 2019 study by the University of Chicago, commissioned by the U.S. government, found 790,000 children, some as young as 5, were working on Ivory Coast cocoa plantations. The situation was similar in neighboring Ghana, researchers found.

The U.S. government has long recognized that child labor is a major problem in the Ivory Coast. The Department of Labor reported in 2021 that “children in Côte d’Ivoire are subjected to the worst forms of child labor, including in the harvesting of cocoa and coffee.”

The State Department in a recent report said that agriculture companies in the Ivory Coast rely on child labor to produce a range of products, including cocoa. The department said this year that human traffickers “exploit Ivoirian boys and boys from West African countries, especially Burkina Faso, in forced labor in agriculture, especially cocoa production."

To try to force companies to abandon cocoa produced by child labor, International Rights Advocates has sued some of the world’s large chocolate companies over the use of child labor in harvesting cocoa beans. It lost a case before the Supreme Court in 2021. Several others are pending.

Pressured by lawmakers and advocates, major chocolate makers in 2001 agreed to stop purchasing cocoa produced by child labor. That goal, experts and industry officials say, has not been met.

“These companies kept saying, ‘We can’t trace it back.’ That’s BS," said former Sen. Tom Harkin, who led a push for legislation to reform the industry, but ended up agreeing to a protocol that allows corporations to regulate themselves. “They just won’t do it because it will cost them money.”

Harkin said Americans don’t realize the treats they hand their children originate with child abuse.

“It’s not just the chocolate you eat, it’s the chocolate syrup you put on your ice cream, the cocoa you drink, the chocolate chip cookies you bake," he said.

The World Cocoa Foundation, which represents major cocoa companies, said it is committed to “improving livelihoods of cocoa farmers and their communities.”

A Hershey spokesperson said the company “does not tolerate child labor within our supply chain.” Cargill, Nestle and Mars did not respond to requests for comment. Their websites all describe their work to end child labor in cocoa plantations.

Ivory Coast officials have said they are taking steps to eradicate child labor but blocking imports of the nation's cocoa would devastate the nation's economy.

“We don’t want to un-employ the whole country,” said Collingsworth, the labor advocate who brought Tuesday's lawsuit. “We just want children replaced by adults in cocoa plantations.”

Collingsworth was in the Ivory Coast investigating working conditions when he noticed children chopping through brush and harvesting cocoa. He pulled out a phone and took video and photographs of the boys and girls at work. He also stopped by a nearby processing facility and took a photos of burlap sacks with labels of U.S. companies.

International Rights Advocates decided to petition the CBP to block imports of the cocoa, filing a 24-page petition in 2020 asking the agency take such action. The petition contained what it said was photographic and other evidence detailing how the companies were violating the law.

Collingsworth said his group also provided CBP with interviews with children as young as 12 who said their wages were being withheld, and that they had been tricked by recruiters into working long hours on a false promise they would be given land of their own.

CBP failed to take any action on the petition, the lawsuit alleges.

union busting!!!

Workers Fighting Union-Busting May Have a New Legal Tool at Their Disposal

A class-action lawsuit against a California-based grocery retailer could set a new precedent against union-busters.

By Sam Knight , TRUTHOUT

Published April 23, 2023

A company accused of lying about retirement benefits to stop workers from organizing can be sued in a class-action lawsuit, a federal judge ruled.

The decision came on April 7 after the defendant, the California-based grocery retailer Save Mart Supermarkets, asked the judge to dismiss the case, which experts are calling a creative use of labor law against union-busting.

The suit hinges on promises made by managers about retirement benefits to undercut the appeal of union membership to employees, a common tactic in campaigns against labor organizing. A ruling against Save Mart could haunt companies that have used similar tactics for decades.

“Unions need to address large companies’ anti-union tactics any way they can, especially given how weak our labor laws have become,” said Naomi Soldon, partner of the union-side labor law firm Soldon McCoy, which isn’t representing anyone in the dispute. Soldon told Truthout that the case takes a “novel approach” to fighting union-busters, and a decision in favor of the workers “should help organizing drives, in general, as it shows employees that they have rights,” which unions can help enforce.

U.S. District Judge William Orrick said the lawsuit against Save Mart may proceed based on allegations of “two misrepresentations” by the company; one stems from promises of nonunion retirement benefits “as good or better than those of their union counterparts,” the other pertains to managers having told employees to retire earlier than they should have to maximize benefits and income.

The benefits offers were made by Save Mart as part of a strategy to undermine organizers with the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), lawyers for the plaintiffs allege.

Save Mart operates more than 200 grocery stores with more than 14,000 workers in California and Nevada under different retail brand names, including Lucky, FoodMaxx, Lucky California and Save Mart itself. The company was listed by Forbes last year as the 109th- largest private employer in the U.S. with some $5 billion in revenue. UFCW local chapters in California represent about 11,500 Save Mart workers.

For years, Save Mart did provide similar retirement benefits to nonunion workers, in dollar amounts. But the terms of benefits to union workers were binding, as per the collective bargaining agreement governing them, while nonunion retirees were compensated at the discretion of management.

In April 2022, shortly after Save Mart’s longtime owners sold the company to a private equity firm, Kingswood Capital Management LP, management took benefits away from nonunion retirees, many of whom had worked for Save Mart for decades. Thus emerged the class- action suit, which features four lead plaintiffs who spent a total of 146 years working for Save Mart companies.

“Put simply, Save Mart made false assurances about [its nonunion retirement plan] benefits as a means of suppressing union enrollment among Save Mart employees,” lawyers for the plaintiffs alleged. They estimated that their clients represent a class that could consist of thousands of workers who are owed “hundreds of millions of dollars.”

The plaintiffs’ complaint outlined how Save Mart, deceptively, touted the quality of its benefits as part of a relentless union-busting strategy orchestrated at the highest level of the corporate hierarchy. When the company opened a new store, for example, executives and high-ranking human resources employees would descend on the staff with generous promises to diminish the appeal of organizing, the filing alleged.

“In these meetings, the HR representative(s) and company executive were trained to communicate that employees should not pay dues to join the union, since the non-union benefits — including retirement benefits — would always be as good as or better than the benefits enjoyed by union employees,” the complaint stated.

Claims about benefits were also invoked by managers at these meetings to counter arguments made by “employees who were union members at their prior location [and] expressed concern about losing their union benefits,” according to the plaintiffs. Similar meetings were held at any store playing host to an organizing drive, if executives or HR got wind of the campaign.

“Internally, these meetings were referred to as ‘the roadshow’ or ‘kumbaya’ meetings because ‘the purpose was to foster harmony amongst the employees by reassuring them about their benefits and quelling any desires to give up those benefits’ by unionizing,” the complaint said. “The message worked: many Save Mart stores remained non-union.”

In a twist of irony, the complaint drew heavily on the testimony of HR executives who were, for years, foot soldiers in Save Mart’s union-busting campaigns. They themselves were “shocked” by the withdrawal of benefits after the Kingswood takeover, plaintiffs’ lawyers said, because they “had been communicating to employees for years that the Plan’s medical benefits were guaranteed for life” and “had themselves relied upon this lifetime guarantee” in deciding to give years of their life to Save Mart.

Meanwhile, the union employees that HR spent years attempting to curtail, didn’t have to consider the possibility of losing their benefits because they refused to take their former bosses’ word for it.

“Our members can rest assured they have the benefit of solid successor language which guarantees they will continue to enjoy the benefits of their Union memberships and labor contracts,” UFCW Local 8-Golden State said in a statement reacting to news of the takeover.

Most legal battles against union busters are waged by workers under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the law that grants legal protections to workplace organizing. In recent months, for example, the law has been used by Starbucks workers to win their jobs back after they were fired for supporting union activity.

Worker advocates, however, have been attempting to strengthen the law for decades, arguing that it could do much more to punish tyrannical union-busting bosses. Democrats attempted to pass a major reform bill in 2021, the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, but fell a few Senate votes shy of sending the legislation to President Joe Biden’s desk.

One way the bill would have strengthened the NLRA: It would have allowed workers to sue companies for monetary damages if the firms violate their rights under the law. The Save Mart class action is being brought under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, which established federal standards for employer-provided retirement and health care plans.

Eric Fink, associate professor of Elon University School of Law, echoed Soldon’s analysis, saying that there’s a high threshold under the NLRA for securing charges against union-busting managers who make deceptive claims about benefits, and the remedies are weak.

“Even if the bait-and-switch in this case could be the basis for an unfair labor practice charge, it would require proof that the employer was motivated by anti-union animus, which would be difficult,” he noted.

“More significantly, in contrast to the limited remedies available for [unfair labor practices], the potential remedies in an ERISA suit are substantial,” Fink added. “If this suit is successful, and if other employers anticipate the possibility of facing similar suits, the deterrent effect could be much greater than has been the case with [unfair labor practice] charges (which are not much of a deterrent at all).”

Bosses violate workers’ rights under the NLRA in 41.5 percent of union organizing campaigns, according to a study published in 2019 by the Economic Policy Institute.

The decision came on April 7 after the defendant, the California-based grocery retailer Save Mart Supermarkets, asked the judge to dismiss the case, which experts are calling a creative use of labor law against union-busting.

The suit hinges on promises made by managers about retirement benefits to undercut the appeal of union membership to employees, a common tactic in campaigns against labor organizing. A ruling against Save Mart could haunt companies that have used similar tactics for decades.

“Unions need to address large companies’ anti-union tactics any way they can, especially given how weak our labor laws have become,” said Naomi Soldon, partner of the union-side labor law firm Soldon McCoy, which isn’t representing anyone in the dispute. Soldon told Truthout that the case takes a “novel approach” to fighting union-busters, and a decision in favor of the workers “should help organizing drives, in general, as it shows employees that they have rights,” which unions can help enforce.

U.S. District Judge William Orrick said the lawsuit against Save Mart may proceed based on allegations of “two misrepresentations” by the company; one stems from promises of nonunion retirement benefits “as good or better than those of their union counterparts,” the other pertains to managers having told employees to retire earlier than they should have to maximize benefits and income.

The benefits offers were made by Save Mart as part of a strategy to undermine organizers with the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), lawyers for the plaintiffs allege.

Save Mart operates more than 200 grocery stores with more than 14,000 workers in California and Nevada under different retail brand names, including Lucky, FoodMaxx, Lucky California and Save Mart itself. The company was listed by Forbes last year as the 109th- largest private employer in the U.S. with some $5 billion in revenue. UFCW local chapters in California represent about 11,500 Save Mart workers.

For years, Save Mart did provide similar retirement benefits to nonunion workers, in dollar amounts. But the terms of benefits to union workers were binding, as per the collective bargaining agreement governing them, while nonunion retirees were compensated at the discretion of management.

In April 2022, shortly after Save Mart’s longtime owners sold the company to a private equity firm, Kingswood Capital Management LP, management took benefits away from nonunion retirees, many of whom had worked for Save Mart for decades. Thus emerged the class- action suit, which features four lead plaintiffs who spent a total of 146 years working for Save Mart companies.

“Put simply, Save Mart made false assurances about [its nonunion retirement plan] benefits as a means of suppressing union enrollment among Save Mart employees,” lawyers for the plaintiffs alleged. They estimated that their clients represent a class that could consist of thousands of workers who are owed “hundreds of millions of dollars.”

The plaintiffs’ complaint outlined how Save Mart, deceptively, touted the quality of its benefits as part of a relentless union-busting strategy orchestrated at the highest level of the corporate hierarchy. When the company opened a new store, for example, executives and high-ranking human resources employees would descend on the staff with generous promises to diminish the appeal of organizing, the filing alleged.

“In these meetings, the HR representative(s) and company executive were trained to communicate that employees should not pay dues to join the union, since the non-union benefits — including retirement benefits — would always be as good as or better than the benefits enjoyed by union employees,” the complaint stated.

Claims about benefits were also invoked by managers at these meetings to counter arguments made by “employees who were union members at their prior location [and] expressed concern about losing their union benefits,” according to the plaintiffs. Similar meetings were held at any store playing host to an organizing drive, if executives or HR got wind of the campaign.

“Internally, these meetings were referred to as ‘the roadshow’ or ‘kumbaya’ meetings because ‘the purpose was to foster harmony amongst the employees by reassuring them about their benefits and quelling any desires to give up those benefits’ by unionizing,” the complaint said. “The message worked: many Save Mart stores remained non-union.”

In a twist of irony, the complaint drew heavily on the testimony of HR executives who were, for years, foot soldiers in Save Mart’s union-busting campaigns. They themselves were “shocked” by the withdrawal of benefits after the Kingswood takeover, plaintiffs’ lawyers said, because they “had been communicating to employees for years that the Plan’s medical benefits were guaranteed for life” and “had themselves relied upon this lifetime guarantee” in deciding to give years of their life to Save Mart.

Meanwhile, the union employees that HR spent years attempting to curtail, didn’t have to consider the possibility of losing their benefits because they refused to take their former bosses’ word for it.

“Our members can rest assured they have the benefit of solid successor language which guarantees they will continue to enjoy the benefits of their Union memberships and labor contracts,” UFCW Local 8-Golden State said in a statement reacting to news of the takeover.

Most legal battles against union busters are waged by workers under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the law that grants legal protections to workplace organizing. In recent months, for example, the law has been used by Starbucks workers to win their jobs back after they were fired for supporting union activity.

Worker advocates, however, have been attempting to strengthen the law for decades, arguing that it could do much more to punish tyrannical union-busting bosses. Democrats attempted to pass a major reform bill in 2021, the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, but fell a few Senate votes shy of sending the legislation to President Joe Biden’s desk.

One way the bill would have strengthened the NLRA: It would have allowed workers to sue companies for monetary damages if the firms violate their rights under the law. The Save Mart class action is being brought under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, which established federal standards for employer-provided retirement and health care plans.

Eric Fink, associate professor of Elon University School of Law, echoed Soldon’s analysis, saying that there’s a high threshold under the NLRA for securing charges against union-busting managers who make deceptive claims about benefits, and the remedies are weak.

“Even if the bait-and-switch in this case could be the basis for an unfair labor practice charge, it would require proof that the employer was motivated by anti-union animus, which would be difficult,” he noted.

“More significantly, in contrast to the limited remedies available for [unfair labor practices], the potential remedies in an ERISA suit are substantial,” Fink added. “If this suit is successful, and if other employers anticipate the possibility of facing similar suits, the deterrent effect could be much greater than has been the case with [unfair labor practice] charges (which are not much of a deterrent at all).”

Bosses violate workers’ rights under the NLRA in 41.5 percent of union organizing campaigns, according to a study published in 2019 by the Economic Policy Institute.

slavery 21st century!!

GEICO Is Trying to Crush Workers’ Attempts to Form an Independent Union

BY Jonah Furman, Labor Notes - truthout

PUBLISHED October 1, 2022

GEICO insurance sales rep Lila Balali first started thinking about a union early in the pandemic. “I didn’t really know what a union was,” she says, “just that it was something for the employee.”

She and her co-workers had been abruptly sent to work from home, where she set up a cramped workspace. “We were taking calls on our cell phones, 40 hours a week, our phone to our ear,” she recalls. “You couldn’t get reimbursed or provided a headset.

“A billion-dollar company — a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary, a Warren Buffet company — was having us go on our cell phones. They passed the cost of business on to us. They didn’t want to spend $1,000 on each associate, and we couldn’t stop them.”

This year, she and her co-workers in Buffalo launched GEICO United, an effort to form an independent union at the insurance giant. GEICO has 2,600 employees in Buffalo, making it one of the area’s largest employers. The union would be the first at the company, although more than 50,000 workers at other Berkshire Hathaway companies are unionized, including rail workers at BNSF.

“The System Is Flawed”

The pandemic did more than send GEICO workers home. It also severely hit GEICO’s bottom line; the company had two of its worst quarters ever in late 2021 and early 2022, a product of the surging values of used cars and the increased cost of repairs. This year, citing these factors GEICO stopped selling insurance over the phone in 18 states and closed 38 offices in California.

For workers like Balali, who has worked at GEICO since 2014, lower sales volume has meant no more bonuses, which are based on sales performance. In fact, the company has reassigned about 30 percent of the sales department nationally to other functions. GEICO has also laid off hundreds of workers in other departments.

The pay and treatment at GEICO can be uneven. Department heads are given a pot of money to distribute raises to the workers they supervise, and women and people of color tend to get left behind.

Sometimes there is outright racism. One supervisor Balali had “would walk around and say ‘What’s up, ISIS?’ because I’m Middle Eastern.”

Inspiration Close to Home

At first, thinking about a union was the extent of it. Then the Amazon Labor Union won in Staten Island, and Balali heard about Chris Smalls, an Amazon worker who took on the e-commerce giant and won.

“I read everything I could find online about [Smalls],” says Balali “He was terminated. Just a regular person, an average person. At such a large facility… Chris Smalls showed you can organize a location of 8,000 employees without being an established union.”

Balali had another important source of inspiration. Working from home in Buffalo, she would head down her street, Elmwood Avenue, to Starbucks. There she met a barista named Jaz Brisack, a leader in the Starbucks Workers United effort, who helped win the first-ever Starbucks union at the Elmwood store last December.

Balali started researching. She read Confessions of a Union Buster, Secrets of a Successful Organizer, books by Jane McAlevey, even union constitutions. She watched union movies like Hoffa and Norma Rae. “I just started reading whatever I could find,” she said. “I was obsessed.”

And she started talking to her co-workers. “The sales department is small. I just started reaching out to my friends. They said ‘Yeah, I’m in.’” A group of seven started meeting for breakfast and coffee.

Going Door to Door

Since their job was fully remote, Balali and her core group didn’t have the option of doing union outreach in the break room or in the hallways. “All of our co-workers, who we counted as friends, we haven’t seen in two and a half years,” she said. “New hires? We don’t know who they are. We don’t even talk to them on the phone.”

The GEICO United organizers needed to find a way to reach their 2,600 co-workers in Buffalo.

In New York state, workers in the insurance industry have to be registered as “insurance producers.” Their home addresses are publicly available in a state-run database. So over a period of months, Balali and her co-workers compiled a list of the addresses of GEICO employees in the greater Buffalo area.

Though Balali sells insurance, she doesn’t make cold calls; the sales she handles are initiated by customers who are in the market for an insurance policy. “I was so scared for the first door I knocked on,” she said

“This lady comes out poker-faced. I couldn’t read her, didn’t know her. That first weekend, we had a flyer we made that looked horrible. It was so ugly. I’m standing there, the woman opens the door, I’m looking at the flyer like, ‘Why did I write so much? This is embarrassing.’

“I’m like, ‘We’re trying to make a union.’ She’s shocked. She’s like, ‘I’ll hear your pitch.’ I start laughing, like, ‘We don’t even have a pitch. We’re just employees.’ That softens her up.

“So we’re talking for a while in front of her door. She pauses. It’s a long pause, back to the poker face. I’m like ‘Oh, shit.’

“She calls her husband out. He’s a GEICO employee too. And they both signed right away. They donated. And they’re like, ‘We’re going to get our friends on board.’

“In that first experience we thought, ‘If we want this, we can do this.’ Then we go to the next door and he’s like, ‘I already signed online.’”

Backlash Begins

Balali and her core group collected 200 signatures in a month — some through their online authorization card, others from their expanding canvassing operation. In those early days, Balali estimates, about 80 percent of people would open their doors, and the vast majority would sign a card.

And then, Balali recalls, “the email comes out.”

On August 12, GEICO sent out an email warning its Buffalo employees that union representatives were visiting workers’ homes. The company wrote that it had not “authorized” such visits, and that “you have every right to contact the police.”

In a follow-up email a week later, the company pointed to Starbucks as an example of a union drive that had achieved no benefits for its members. The email touted the raises and benefits that Starbucks gave only at its non-union stores, a practice for which the National Labor Relations Board has since filed a formal complaint against Starbucks.

GEICO United enlisted the help of pro bono lawyers to file unfair labor practice charges. But the damage was done.

Most people stopped opening their doors when organizers would go canvassing. One of the core organizers, a Black worker who has been at the company for a decade and makes less than $20 an hour, backed out for fear of reprisals.

For all these setbacks, though, Balali says the union is still growing, if slowly. More and more of the signatures are coming through the online card — which workers are finding by social media and word of mouth. Sometimes it is management, probing for details, that inadvertently alerts employees to the effort.

She and her co-workers had been abruptly sent to work from home, where she set up a cramped workspace. “We were taking calls on our cell phones, 40 hours a week, our phone to our ear,” she recalls. “You couldn’t get reimbursed or provided a headset.

“A billion-dollar company — a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary, a Warren Buffet company — was having us go on our cell phones. They passed the cost of business on to us. They didn’t want to spend $1,000 on each associate, and we couldn’t stop them.”

This year, she and her co-workers in Buffalo launched GEICO United, an effort to form an independent union at the insurance giant. GEICO has 2,600 employees in Buffalo, making it one of the area’s largest employers. The union would be the first at the company, although more than 50,000 workers at other Berkshire Hathaway companies are unionized, including rail workers at BNSF.

“The System Is Flawed”

The pandemic did more than send GEICO workers home. It also severely hit GEICO’s bottom line; the company had two of its worst quarters ever in late 2021 and early 2022, a product of the surging values of used cars and the increased cost of repairs. This year, citing these factors GEICO stopped selling insurance over the phone in 18 states and closed 38 offices in California.

For workers like Balali, who has worked at GEICO since 2014, lower sales volume has meant no more bonuses, which are based on sales performance. In fact, the company has reassigned about 30 percent of the sales department nationally to other functions. GEICO has also laid off hundreds of workers in other departments.

The pay and treatment at GEICO can be uneven. Department heads are given a pot of money to distribute raises to the workers they supervise, and women and people of color tend to get left behind.

Sometimes there is outright racism. One supervisor Balali had “would walk around and say ‘What’s up, ISIS?’ because I’m Middle Eastern.”

Inspiration Close to Home

At first, thinking about a union was the extent of it. Then the Amazon Labor Union won in Staten Island, and Balali heard about Chris Smalls, an Amazon worker who took on the e-commerce giant and won.

“I read everything I could find online about [Smalls],” says Balali “He was terminated. Just a regular person, an average person. At such a large facility… Chris Smalls showed you can organize a location of 8,000 employees without being an established union.”

Balali had another important source of inspiration. Working from home in Buffalo, she would head down her street, Elmwood Avenue, to Starbucks. There she met a barista named Jaz Brisack, a leader in the Starbucks Workers United effort, who helped win the first-ever Starbucks union at the Elmwood store last December.

Balali started researching. She read Confessions of a Union Buster, Secrets of a Successful Organizer, books by Jane McAlevey, even union constitutions. She watched union movies like Hoffa and Norma Rae. “I just started reading whatever I could find,” she said. “I was obsessed.”

And she started talking to her co-workers. “The sales department is small. I just started reaching out to my friends. They said ‘Yeah, I’m in.’” A group of seven started meeting for breakfast and coffee.

Going Door to Door

Since their job was fully remote, Balali and her core group didn’t have the option of doing union outreach in the break room or in the hallways. “All of our co-workers, who we counted as friends, we haven’t seen in two and a half years,” she said. “New hires? We don’t know who they are. We don’t even talk to them on the phone.”

The GEICO United organizers needed to find a way to reach their 2,600 co-workers in Buffalo.

In New York state, workers in the insurance industry have to be registered as “insurance producers.” Their home addresses are publicly available in a state-run database. So over a period of months, Balali and her co-workers compiled a list of the addresses of GEICO employees in the greater Buffalo area.

Though Balali sells insurance, she doesn’t make cold calls; the sales she handles are initiated by customers who are in the market for an insurance policy. “I was so scared for the first door I knocked on,” she said

“This lady comes out poker-faced. I couldn’t read her, didn’t know her. That first weekend, we had a flyer we made that looked horrible. It was so ugly. I’m standing there, the woman opens the door, I’m looking at the flyer like, ‘Why did I write so much? This is embarrassing.’

“I’m like, ‘We’re trying to make a union.’ She’s shocked. She’s like, ‘I’ll hear your pitch.’ I start laughing, like, ‘We don’t even have a pitch. We’re just employees.’ That softens her up.

“So we’re talking for a while in front of her door. She pauses. It’s a long pause, back to the poker face. I’m like ‘Oh, shit.’

“She calls her husband out. He’s a GEICO employee too. And they both signed right away. They donated. And they’re like, ‘We’re going to get our friends on board.’

“In that first experience we thought, ‘If we want this, we can do this.’ Then we go to the next door and he’s like, ‘I already signed online.’”

Backlash Begins

Balali and her core group collected 200 signatures in a month — some through their online authorization card, others from their expanding canvassing operation. In those early days, Balali estimates, about 80 percent of people would open their doors, and the vast majority would sign a card.

And then, Balali recalls, “the email comes out.”

On August 12, GEICO sent out an email warning its Buffalo employees that union representatives were visiting workers’ homes. The company wrote that it had not “authorized” such visits, and that “you have every right to contact the police.”

In a follow-up email a week later, the company pointed to Starbucks as an example of a union drive that had achieved no benefits for its members. The email touted the raises and benefits that Starbucks gave only at its non-union stores, a practice for which the National Labor Relations Board has since filed a formal complaint against Starbucks.

GEICO United enlisted the help of pro bono lawyers to file unfair labor practice charges. But the damage was done.

Most people stopped opening their doors when organizers would go canvassing. One of the core organizers, a Black worker who has been at the company for a decade and makes less than $20 an hour, backed out for fear of reprisals.

For all these setbacks, though, Balali says the union is still growing, if slowly. More and more of the signatures are coming through the online card — which workers are finding by social media and word of mouth. Sometimes it is management, probing for details, that inadvertently alerts employees to the effort.

slavery 21st century!!!

More US Employers Are Trapping Workers in a New Form of Indentured Servitude

BY Sam Knight, Truthout

PUBLISHED September 19, 2022

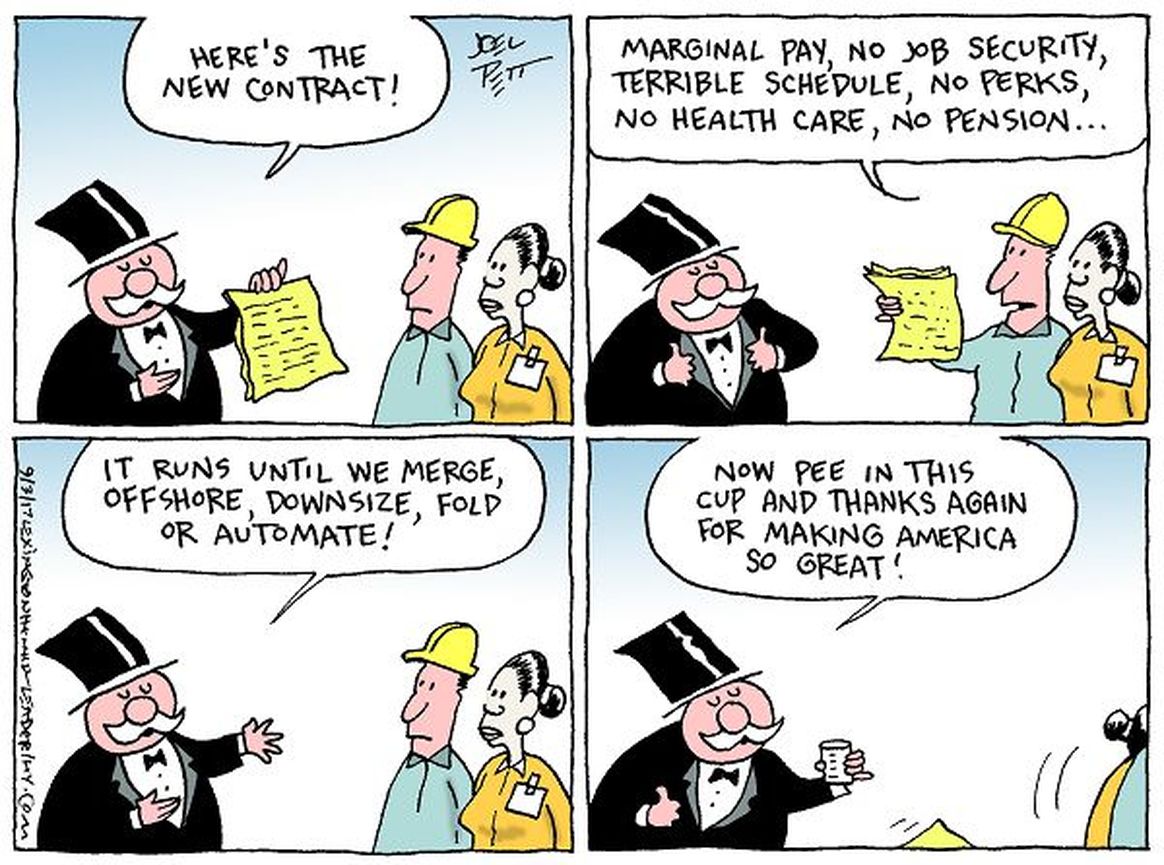

Bosses in industries such as retail, health care and logistics are reverting to an old tactic and trapping people in miserable jobs by threatening to saddle them with debt if they quit. Workers across the United States in fields ranging from nursing to trucking have been discouraged from leaving jobs they hate or can’t afford to keep because employers vow to charge them for training costs if they quit before an arbitrary deadline.

The threats are backed by so-called Training Repayment Agreement Provisions (TRAPs) in employment contracts. The practice has been likened by critics to indentured servitude and peonage — formerly common types of debt bondage in which a borrower was bound to perform labor for a creditor.

TRAPs have recently come under fire from policymakers because of class action litigation against the pet store chain PetSmart, and reporting on the restrictive covenants from a watchdog group called the Student Borrower Protection Center. Earlier this month, the Senate Banking Committee held hearings examining the agreements and other forms of employer-driven debt. In June, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau also launched an investigation of employment arrangements that led to workers owing money to their bosses.

Two workers who are being threatened with thousands of dollars in bills through the enforcement of TRAPs appeared before the banking committee on September 7. BreAnn Scally, the lead plaintiff in the class action against PetSmart, told lawmakers about how she was left owing $5,500 to the company for a dog “Grooming Academy” that was initially advertised as free. Registered nurse Cassie Pennings testified about being stuck with $7,500, “more than six months’ rent,” after leaving one hospital job because she was appalled by staffing ratios during the COVID-19 pandemic and didn’t want to be complicit in neglecting patients.

Although the pair came from different industries, they both detailed callous indifference from their ex-managers in response to their grievances. “Despite being one of the most profitable health care systems in the nation, my former employer responded to cries for help from the front line with breakfast burritos and free water bottles,” Pennings said. Scally recalled how one manager told her she could work her way out of debt simply by “upselling” or convincing customers to buy more pet grooming products and services. She said that she upsold $6,000 worth of products but was still charged the full amount for the debt, months after she left the job.

The dollar value attached by each company to the cost of training appeared to have been pulled from thin air. “I thought I was going to get important and valuable training, but it wasn’t anything like that,” Scally said. “I didn’t get any kind of license or accreditation or anything, and my actual training was only a few weeks.” Pennings also told lawmakers that she doubted the $7,500 price tag placed on the cost of her training regimen.

At a second hearing on September 13, one of Scally’s lawyers, David Seligman, told the Senate Banking Committee that TRAPs are used by managers to leave workers “stuck with low pay, dangerous conditions, abusive treatment, or work that does not allow them to advance professionally.” The chair of the committee, Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown, was unimpressed with the managerial tactic.

“Last I checked, indentured servitude was illegal in the United States. But it looks like some enterprising companies are rebranding it, with these new employment contracts,” Senator Brown said. His office told Truthout that the lawmaker is currently “considering legislation” that would rein in the use of TRAPs by employers, and said he “will work with the [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau] to ensure that consumers are protected from predatory consumer products like TRAPs.”

Indentured servitude was pioneered during the British colonial period to finance the travel of European migrant laborers to North America. Wealthy individuals who paid for the travel were allowed for years to closely control and abuse those who made the voyage. Although the United States technically banned indentured servitude with the abolition of chattel slavery and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, U.S. railroad companies effectively brought Chinese workers over as indentured servants in the postbellum 19th century for five-year contracts with terms that brought the workers “low wages and … substandard living conditions.”

“The law does not permit employers or others to provide a work opportunity in exchange for a worker’s promise to indenture themselves to their employer through debt,” Seligman said. “These sorts of work arrangements harken back to nineteenth century peonage used to subjugate former slaves, and they are precisely the kind of exploitation that our anti-trafficking and peonage laws were designed to prohibit.” Peonage was imposed on former slaves in the southern United States during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era through sharecropping arrangements and fines levied by racist law enforcement.

Although critics question the legality of TRAPs, a legal analysis published last year found that courts generally uphold the agreements in challenges brought under anti-kickback provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act, the law establishing a federal minimum wage. However, the author of the study, Loyola Marymount associate law professor Jonathan F. Harris, said another type of legal challenge might prove more successful: courts could refuse to enforce TRAP contract language under the so-called unconscionability doctrine, a legal principle that allows judges to void agreements containing unreasonable terms dictated by a party “with superior bargaining power.” In 2000, the study noted, a federal judge in Manhattan nullified one employment agreement in the financial services industry, ruling that the language of the contract “approaches indentured servitude.”

TRAPs have been commonly used by employers since the 1990s, but they were almost exclusively reserved then for highly specialized workers such as engineers or airline pilots. As markets became increasingly concentrated and union power was diminished by policymakers into the 21st century, bosses used their growing dominance to impose TRAPs on rank-and-file workers, such as “truckers, nurses, mechanics, electricians, salespeople, paramedics, flight attendants, bank workers, repairmen, and social workers,” as Harris’s study detailed. “While such jobs used to be middle class and highly unionized, many workers in these sectors now struggle financially, and unionization levels have dropped,” according to Harris.

In his study, Harris noted that there has been little evidence-based analysis of the agreements and their impact on labor markets but said the use of them is on the rise, and that the vast majority never see any kind of legal scrutiny. “For every [TRAP] that is the subject of a court opinion, tens of thousands remain unchallenged,” he noted. What empirical analysis has been done has shown bosses primarily using TRAPs for “employee immobility” — to obstruct workers from leaving jobs. Harris also found anecdotal evidence from the nursing sector, which showed the restrictive agreements mostly wielded by employers “unable or unwilling to compete on wages and other benefits.”

Payday advances were another type of employer-driven debt examined by the Senate Banking Committee. Seligman highlighted the case of Marriott workers in Philadelphia who became dependent on short-term loans from the company credit union because “scheduling practices made it difficult for them to earn consistent income without getting a second job.” Franchising agreements that misclassify workers as independent contractors can also leave low-wage earners heavily in debt to bosses because of franchising fees, he told the committee.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau investigation into employer-driven debt will be examining franchising agreements among other job arrangements that “involve deferred payment to the employer or an associated entity for employer mandated training, equipment, and other expenses.” The agency will also be looking at TRAPs, though it described the arrangements as “Training Repayment Agreements.” There’s also an ongoing bureau investigation of payday advances (so-called “earned wage access” products) which was launched in February.

Whatever the terms used and however the debt originated, employer-driven loans have not proliferated because workers “lack access to credit,” as Seligman told the banking committee, but because workers aren’t paid enough. “And far too many employers seek to shift onto their workers their own costs while undermining their workers’ bargaining power by making it costly for them to seek out jobs where they might be treated better or paid more,” he added.

The threats are backed by so-called Training Repayment Agreement Provisions (TRAPs) in employment contracts. The practice has been likened by critics to indentured servitude and peonage — formerly common types of debt bondage in which a borrower was bound to perform labor for a creditor.

TRAPs have recently come under fire from policymakers because of class action litigation against the pet store chain PetSmart, and reporting on the restrictive covenants from a watchdog group called the Student Borrower Protection Center. Earlier this month, the Senate Banking Committee held hearings examining the agreements and other forms of employer-driven debt. In June, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau also launched an investigation of employment arrangements that led to workers owing money to their bosses.

Two workers who are being threatened with thousands of dollars in bills through the enforcement of TRAPs appeared before the banking committee on September 7. BreAnn Scally, the lead plaintiff in the class action against PetSmart, told lawmakers about how she was left owing $5,500 to the company for a dog “Grooming Academy” that was initially advertised as free. Registered nurse Cassie Pennings testified about being stuck with $7,500, “more than six months’ rent,” after leaving one hospital job because she was appalled by staffing ratios during the COVID-19 pandemic and didn’t want to be complicit in neglecting patients.

Although the pair came from different industries, they both detailed callous indifference from their ex-managers in response to their grievances. “Despite being one of the most profitable health care systems in the nation, my former employer responded to cries for help from the front line with breakfast burritos and free water bottles,” Pennings said. Scally recalled how one manager told her she could work her way out of debt simply by “upselling” or convincing customers to buy more pet grooming products and services. She said that she upsold $6,000 worth of products but was still charged the full amount for the debt, months after she left the job.

The dollar value attached by each company to the cost of training appeared to have been pulled from thin air. “I thought I was going to get important and valuable training, but it wasn’t anything like that,” Scally said. “I didn’t get any kind of license or accreditation or anything, and my actual training was only a few weeks.” Pennings also told lawmakers that she doubted the $7,500 price tag placed on the cost of her training regimen.

At a second hearing on September 13, one of Scally’s lawyers, David Seligman, told the Senate Banking Committee that TRAPs are used by managers to leave workers “stuck with low pay, dangerous conditions, abusive treatment, or work that does not allow them to advance professionally.” The chair of the committee, Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown, was unimpressed with the managerial tactic.

“Last I checked, indentured servitude was illegal in the United States. But it looks like some enterprising companies are rebranding it, with these new employment contracts,” Senator Brown said. His office told Truthout that the lawmaker is currently “considering legislation” that would rein in the use of TRAPs by employers, and said he “will work with the [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau] to ensure that consumers are protected from predatory consumer products like TRAPs.”

Indentured servitude was pioneered during the British colonial period to finance the travel of European migrant laborers to North America. Wealthy individuals who paid for the travel were allowed for years to closely control and abuse those who made the voyage. Although the United States technically banned indentured servitude with the abolition of chattel slavery and the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, U.S. railroad companies effectively brought Chinese workers over as indentured servants in the postbellum 19th century for five-year contracts with terms that brought the workers “low wages and … substandard living conditions.”

“The law does not permit employers or others to provide a work opportunity in exchange for a worker’s promise to indenture themselves to their employer through debt,” Seligman said. “These sorts of work arrangements harken back to nineteenth century peonage used to subjugate former slaves, and they are precisely the kind of exploitation that our anti-trafficking and peonage laws were designed to prohibit.” Peonage was imposed on former slaves in the southern United States during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era through sharecropping arrangements and fines levied by racist law enforcement.

Although critics question the legality of TRAPs, a legal analysis published last year found that courts generally uphold the agreements in challenges brought under anti-kickback provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act, the law establishing a federal minimum wage. However, the author of the study, Loyola Marymount associate law professor Jonathan F. Harris, said another type of legal challenge might prove more successful: courts could refuse to enforce TRAP contract language under the so-called unconscionability doctrine, a legal principle that allows judges to void agreements containing unreasonable terms dictated by a party “with superior bargaining power.” In 2000, the study noted, a federal judge in Manhattan nullified one employment agreement in the financial services industry, ruling that the language of the contract “approaches indentured servitude.”

TRAPs have been commonly used by employers since the 1990s, but they were almost exclusively reserved then for highly specialized workers such as engineers or airline pilots. As markets became increasingly concentrated and union power was diminished by policymakers into the 21st century, bosses used their growing dominance to impose TRAPs on rank-and-file workers, such as “truckers, nurses, mechanics, electricians, salespeople, paramedics, flight attendants, bank workers, repairmen, and social workers,” as Harris’s study detailed. “While such jobs used to be middle class and highly unionized, many workers in these sectors now struggle financially, and unionization levels have dropped,” according to Harris.

In his study, Harris noted that there has been little evidence-based analysis of the agreements and their impact on labor markets but said the use of them is on the rise, and that the vast majority never see any kind of legal scrutiny. “For every [TRAP] that is the subject of a court opinion, tens of thousands remain unchallenged,” he noted. What empirical analysis has been done has shown bosses primarily using TRAPs for “employee immobility” — to obstruct workers from leaving jobs. Harris also found anecdotal evidence from the nursing sector, which showed the restrictive agreements mostly wielded by employers “unable or unwilling to compete on wages and other benefits.”

Payday advances were another type of employer-driven debt examined by the Senate Banking Committee. Seligman highlighted the case of Marriott workers in Philadelphia who became dependent on short-term loans from the company credit union because “scheduling practices made it difficult for them to earn consistent income without getting a second job.” Franchising agreements that misclassify workers as independent contractors can also leave low-wage earners heavily in debt to bosses because of franchising fees, he told the committee.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau investigation into employer-driven debt will be examining franchising agreements among other job arrangements that “involve deferred payment to the employer or an associated entity for employer mandated training, equipment, and other expenses.” The agency will also be looking at TRAPs, though it described the arrangements as “Training Repayment Agreements.” There’s also an ongoing bureau investigation of payday advances (so-called “earned wage access” products) which was launched in February.

Whatever the terms used and however the debt originated, employer-driven loans have not proliferated because workers “lack access to credit,” as Seligman told the banking committee, but because workers aren’t paid enough. “And far too many employers seek to shift onto their workers their own costs while undermining their workers’ bargaining power by making it costly for them to seek out jobs where they might be treated better or paid more,” he added.

CEO Who Got $940 Million Richer in Pandemic Is Behind Starbucks Union-Busting

BY Jake Johnson, Common Dreams

PUBLISHED August 31, 2022

An analysis released Wednesday shows that the multi-billionaire chief executive spearheading Starbucks’ aggressive and unlawful union-busting campaign has gotten $940 million richer during the coronavirus pandemic as employees at the coffee chain have struggled to get by on low wages.

Compiled by the progressive group Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF), “Billion-Dollar Union Busters: How Starbucks and Its Rich CEO Are Stifling Worker Organizing” was published as the nationwide unionization drive at the coffee chain continues to grow in the face of increasingly brazen opposition from management, with more than 200 locations voting to join Workers United since December 2021.

“Starbucks and its billionaire CEO, Howard Schultz, can well-afford to improve employees’ pay and working conditions through unionization,” reads the new report. “Schultz’s personal fortune increased by nearly $1 billion during the Covid pandemic, leaping to nearly $4 billion today. Over the last decade his wealth has increased by about $640,000 a day on average, or more money in a single day than most of his store employees are likely to make from Starbucks in a lifetime.”

Schultz retook the helm at Starbucks in an interim capacity earlier this year as the unionization push spread rapidly to coffee shops across the country. Given his long history of union-busting, Schultz’s return was widely viewed as part of the corporation’s attempt to crush organizing momentum.

While recent data shows the union drive slowed slightly last month, the number of stores filing for union elections and winning is still rising at a striking pace, an indication that Starbucks’ aggressive anti-union tactics — from firing organizers to denying unionized workers wage and benefit improvements — have thus far been largely unsuccessful.

“As of early August 2022, Starbucks had racked up 276 unfair labor practice charges,” ATF notes in its report, which comes just ahead of Labor Day.

Zachary Tashman, a research and policy associate at ATF and the new report’s lead author, said in a statement Wednesday that “the ruthless union-busting strategy used by Starbucks and its billionaire CEO is a perfect example of how far wealthy corporations are willing to go to keep their profits concentrated in just a few hands.”

The report points out that Starbucks netted $4.1 billion in pre-tax profits in 2021, up 457% from the previous year, when the coronavirus pandemic took a significant toll on operations.

“Starbucks can certainly afford to pay its workers more and offer them better benefits,” the report continues. “Kevin Johnson, the CEO of Starbucks until March of this year, was rewarded with $20.4 million in compensation in 2021, a bump of nearly $5.8 million (39.3%) from 2020.”