TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

WELCOME TO REALITY ~ TRIVIA

currents

hi lites of innovation and research to better

mankind

things that could be achieved if we had a real government!!!

august 2022

a country run by intelligent people with a real government!!!

Whistle blows in Germany for world's first hydrogen train fleet

Agence France-Presse - raw story

August 24, 2022

Germany on Wednesday will inaugurate a railway line powered entirely by hydrogen, a "world first" and a major step forward for green train transport despite nagging supply challenges.

A fleet of 14 trains provided by French industrial giant Alstom to the German state Lower Saxony will replace the diesel locomotives on the 100 kilometres (60 miles) of track connecting the cities of Cuxhaven, Bremerhaven, Bremervoerde and Buxtehude near Hamburg.

"Whatever the time of day, passengers will travel on this route thanks to hydrogen", Stefan Schrank, project manager at Alstom, told AFP, hailing a "world first".

Hydrogen trains have become a promising way to decarbonize the rail sector and replace diesel, which still powers 20 percent of journeys in Germany.

Billed as a "zero emission" mode of transport, the trains mix hydrogen on board with oxygen present in the ambient air, thanks to a fuel cell installed in the roof. This produces the electricity needed to pull the train.

Run for its money

Designed in the southern French town of Tarbes and assembled in Salzgitter in central Germany, Alstom's trains -- called Coradia iLint -- are trailblazers in the sector.

The project drew investment of "several tens of millions of euros" and created jobs for up to 80 employees in the two countries, according to Alstom.

Commercial trials have been carried out since 2018 on the line with two hydrogen trains but now the entire fleet is adopting the ground-breaking technology.

The French group has inked four contracts for several dozen trains between Germany, France and Italy, with no sign of demand waning.

In Germany alone "between 2,500 and 3,000 diesel trains could be replaced by hydrogen models", Schrank estimates.

"By 2035, around 15 to 20 percent of the regional European market could run on hydrogen," Alexandre Charpentier, rail expert at consultancy Roland Berger, told AFP.

Hydrogen trains are particularly attractive on short regional lines where the cost of a transition to electric outstrips the profitability of the route.

Currently, around one out of two regional trains in Europe runs on diesel.

But Alstom's competitors are ready to give it a run for its money. German behemoth Siemens unveiled a prototype hydrogen train with national rail company Deutsche Bahn in May, with a view to a roll-out in 2024.

But, despite the attractive prospects, "there are real barriers" to a big expansion with hydrogen, Charpentier said.

For starters, trains are not the only means of transport hungry for the fuel.

The entire sector, whether it be road vehicles or aircraft, not to mention heavy industry such as steel and chemicals, are eyeing hydrogen to slash CO2 emissions.

Colossal investment

Although Germany announced in 2020 an ambitious seven-billion-euro (-dollar) plan to become a leader in hydrogen technologies within a decade, the infrastructure is still lacking in Europe's top economy.

It is a problem seen across the continent, where colossal investment would be needed for a real shift to hydrogen.

"For this reason, we do not foresee a 100-percent replacement of diesel trains with hydrogen," Charpentier said.

Furthermore, hydrogen is not necessarily carbon-free: only "green hydrogen", produced using renewable energy, is considered sustainable by experts.

Other, more common manufacturing methods exist, but they emit greenhouse gases because they are made from fossil fuels.

The Lower Saxony line will in the beginning have to use a hydrogen by-product of certain industries such as the chemical sector.

The French research institute IFP specializing in energy issues says that hydrogen is currently "95 percent derived from the transformation of fossil fuels, almost half of which come from natural gas".

Europe's enduring reliance on gas from Russia amid massive tensions over the Kremlin's invasion of Ukraine poses major challenges for the development of hydrogen in rail transport.

"Political leaders will have to decide which sector to prioritize when determining what the production of hydrogen will or won't go to," Charpentier said.

Germany will also have to import massively to meet its needs.

Partnerships have recently been signed with India and Morocco, and an agreement to import hydrogen from Canada was on the agenda this week during a visit by Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

A fleet of 14 trains provided by French industrial giant Alstom to the German state Lower Saxony will replace the diesel locomotives on the 100 kilometres (60 miles) of track connecting the cities of Cuxhaven, Bremerhaven, Bremervoerde and Buxtehude near Hamburg.

"Whatever the time of day, passengers will travel on this route thanks to hydrogen", Stefan Schrank, project manager at Alstom, told AFP, hailing a "world first".

Hydrogen trains have become a promising way to decarbonize the rail sector and replace diesel, which still powers 20 percent of journeys in Germany.

Billed as a "zero emission" mode of transport, the trains mix hydrogen on board with oxygen present in the ambient air, thanks to a fuel cell installed in the roof. This produces the electricity needed to pull the train.

Run for its money

Designed in the southern French town of Tarbes and assembled in Salzgitter in central Germany, Alstom's trains -- called Coradia iLint -- are trailblazers in the sector.

The project drew investment of "several tens of millions of euros" and created jobs for up to 80 employees in the two countries, according to Alstom.

Commercial trials have been carried out since 2018 on the line with two hydrogen trains but now the entire fleet is adopting the ground-breaking technology.

The French group has inked four contracts for several dozen trains between Germany, France and Italy, with no sign of demand waning.

In Germany alone "between 2,500 and 3,000 diesel trains could be replaced by hydrogen models", Schrank estimates.

"By 2035, around 15 to 20 percent of the regional European market could run on hydrogen," Alexandre Charpentier, rail expert at consultancy Roland Berger, told AFP.

Hydrogen trains are particularly attractive on short regional lines where the cost of a transition to electric outstrips the profitability of the route.

Currently, around one out of two regional trains in Europe runs on diesel.

But Alstom's competitors are ready to give it a run for its money. German behemoth Siemens unveiled a prototype hydrogen train with national rail company Deutsche Bahn in May, with a view to a roll-out in 2024.

But, despite the attractive prospects, "there are real barriers" to a big expansion with hydrogen, Charpentier said.

For starters, trains are not the only means of transport hungry for the fuel.

The entire sector, whether it be road vehicles or aircraft, not to mention heavy industry such as steel and chemicals, are eyeing hydrogen to slash CO2 emissions.

Colossal investment

Although Germany announced in 2020 an ambitious seven-billion-euro (-dollar) plan to become a leader in hydrogen technologies within a decade, the infrastructure is still lacking in Europe's top economy.

It is a problem seen across the continent, where colossal investment would be needed for a real shift to hydrogen.

"For this reason, we do not foresee a 100-percent replacement of diesel trains with hydrogen," Charpentier said.

Furthermore, hydrogen is not necessarily carbon-free: only "green hydrogen", produced using renewable energy, is considered sustainable by experts.

Other, more common manufacturing methods exist, but they emit greenhouse gases because they are made from fossil fuels.

The Lower Saxony line will in the beginning have to use a hydrogen by-product of certain industries such as the chemical sector.

The French research institute IFP specializing in energy issues says that hydrogen is currently "95 percent derived from the transformation of fossil fuels, almost half of which come from natural gas".

Europe's enduring reliance on gas from Russia amid massive tensions over the Kremlin's invasion of Ukraine poses major challenges for the development of hydrogen in rail transport.

"Political leaders will have to decide which sector to prioritize when determining what the production of hydrogen will or won't go to," Charpentier said.

Germany will also have to import massively to meet its needs.

Partnerships have recently been signed with India and Morocco, and an agreement to import hydrogen from Canada was on the agenda this week during a visit by Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

Scientists unveil bionic robo-fish to remove microplastics from seas

Sofia Quaglia - the guardian

Wed 22 Jun 2022 07.47 EDT

Scientists have designed a tiny robot-fish that is programmed to remove microplastics from seas and oceans by swimming around and adsorbing them on its soft, flexible, self-healing body.

Microplastics are the billions of tiny plastic particles which fragment from the bigger plastic things used every day such as water bottles, car tyres and synthetic T-shirts. They are one of the 21st century’s biggest environmental problems because once they are dispersed into the environment through the breakdown of larger plastics they are very hard to get rid of, making their way into drinking water, produce, and food, harming the environment and animal and human health.

“It is of great significance to develop a robot to accurately collect and sample detrimental microplastic pollutants from the aquatic environment,” said Yuyan Wang, a researcher at the Polymer Research Institute of Sichuan University and one of the lead authors on the study. Her team’s novel invention is described in a research paper in the journal Nano Letters. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of such soft robots.”

Researchers at Sichuan University have revealed an innovative solution to track down these pollutants when it comes to water contamination: designing a tiny self-propelled robo-fish that can swim around, latch on to free-floating microplastics, and fix itself if it gets cut or damaged while on its expedition.

The robo-fish is just 13mm long, and thanks to a light laser system in its tail, swims and flaps around at almost 30mm a second, similar to the speed at which plankton drift around in moving water.

The researchers created the robot from materials inspired by elements that thrive in the sea: mother-of-pearl, also known as nacre, which is the interior covering of clam shells. The team created a material similar to nacre by layering various microscopic sheets of molecules according to nacre’s specific chemical gradient.

This made them a robo-fish that is stretchy, flexible to twist, and even able to pull up to 5kg in weight, according to the study. Most importantly, the bionic fish can adsorb nearby free-floating bits of microplastics because the organic dyes, antibiotics, and heavy metals in the microplastics have strong chemical bonds and electrostatic interactions with the fish’s materials. That makes them cling on to its surface, so the fish can collect and remove microplastics from the water. “After the robot collects the microplastics in the water, the researchers can further analyse the composition and physiological toxicity of the microplastics,” said Wang.

Plus, the newly created material also seems to have regenerative abilities, said Wang, who specialises in the development of self-healing materials. So the robot fish can heal itself to 89% of its ability and continue adsorbing even in the case it experiences some damage or cutting – which could happen often if it goes hunting for pollutants in rough waters.

This is just a proof of concept, Wang notes, and much more research is needed – especially into how this could be deployed in the real world. For example, the soft robot currently only works on water surfaces, so Wang’s team will soon be working on more functionally complex robo-fish that can go deeper under the water. Still, this bionic design could offer a launchpad for other similar projects, Wang said. “I think nanotechnology holds great promise for trace adsorption, collection, and detection of pollutants, improving intervention efficiency while reducing operating costs.”

Indeed, nanotechnology will be one of the most important players in the fight against microplastics, according to Philip Demokritou, the director of the Nanoscience and Advanced Materials Research Center at Rutgers University, who was not involved in this study.

Demokritou’s lab also focuses on using nanotechnology to get rid of microplastics from the planet – but instead of cleaning them up, they are working on substituting them. This week, in the journal Nature Food, he announced the invention of a new plant-based spray coating which can serve as an environmentally friendly alternative to plastic food wraps. Their case study showed that this starch-based fibre spray can fend off pathogens and guard against transportation damage just as well, if not better, than current plastic packaging options.

“The motto for the last 40 to 50 years for the chemical industry is: let’s make chemicals, let’s make materials, put them out there and then clean the mess 20, or 30 years later,” said Demokritou. “That’s not a sustainable model. So can we synthesise safer design materials? Can we derive materials from food waste as part of the circular economy and turn them into useful materials that we can use to address this problem?”

This is low-hanging fruit for the field of nanotechnology, Demokritou said, and as research into materials gets better so will the multi-pronged approach of substituting plastic in our daily lives and filtering out its microplastic residue from the environment.

“But there’s a big distinction between an invention and an innovation,” Demokritou said. “Invention is something that nobody has thought about yet. Right? But innovation is something that will change people’s lives, because it makes it to commercialisation, and it can be scaled.”

Microplastics are the billions of tiny plastic particles which fragment from the bigger plastic things used every day such as water bottles, car tyres and synthetic T-shirts. They are one of the 21st century’s biggest environmental problems because once they are dispersed into the environment through the breakdown of larger plastics they are very hard to get rid of, making their way into drinking water, produce, and food, harming the environment and animal and human health.

“It is of great significance to develop a robot to accurately collect and sample detrimental microplastic pollutants from the aquatic environment,” said Yuyan Wang, a researcher at the Polymer Research Institute of Sichuan University and one of the lead authors on the study. Her team’s novel invention is described in a research paper in the journal Nano Letters. “To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of such soft robots.”

Researchers at Sichuan University have revealed an innovative solution to track down these pollutants when it comes to water contamination: designing a tiny self-propelled robo-fish that can swim around, latch on to free-floating microplastics, and fix itself if it gets cut or damaged while on its expedition.

The robo-fish is just 13mm long, and thanks to a light laser system in its tail, swims and flaps around at almost 30mm a second, similar to the speed at which plankton drift around in moving water.

The researchers created the robot from materials inspired by elements that thrive in the sea: mother-of-pearl, also known as nacre, which is the interior covering of clam shells. The team created a material similar to nacre by layering various microscopic sheets of molecules according to nacre’s specific chemical gradient.

This made them a robo-fish that is stretchy, flexible to twist, and even able to pull up to 5kg in weight, according to the study. Most importantly, the bionic fish can adsorb nearby free-floating bits of microplastics because the organic dyes, antibiotics, and heavy metals in the microplastics have strong chemical bonds and electrostatic interactions with the fish’s materials. That makes them cling on to its surface, so the fish can collect and remove microplastics from the water. “After the robot collects the microplastics in the water, the researchers can further analyse the composition and physiological toxicity of the microplastics,” said Wang.

Plus, the newly created material also seems to have regenerative abilities, said Wang, who specialises in the development of self-healing materials. So the robot fish can heal itself to 89% of its ability and continue adsorbing even in the case it experiences some damage or cutting – which could happen often if it goes hunting for pollutants in rough waters.

This is just a proof of concept, Wang notes, and much more research is needed – especially into how this could be deployed in the real world. For example, the soft robot currently only works on water surfaces, so Wang’s team will soon be working on more functionally complex robo-fish that can go deeper under the water. Still, this bionic design could offer a launchpad for other similar projects, Wang said. “I think nanotechnology holds great promise for trace adsorption, collection, and detection of pollutants, improving intervention efficiency while reducing operating costs.”

Indeed, nanotechnology will be one of the most important players in the fight against microplastics, according to Philip Demokritou, the director of the Nanoscience and Advanced Materials Research Center at Rutgers University, who was not involved in this study.

Demokritou’s lab also focuses on using nanotechnology to get rid of microplastics from the planet – but instead of cleaning them up, they are working on substituting them. This week, in the journal Nature Food, he announced the invention of a new plant-based spray coating which can serve as an environmentally friendly alternative to plastic food wraps. Their case study showed that this starch-based fibre spray can fend off pathogens and guard against transportation damage just as well, if not better, than current plastic packaging options.

“The motto for the last 40 to 50 years for the chemical industry is: let’s make chemicals, let’s make materials, put them out there and then clean the mess 20, or 30 years later,” said Demokritou. “That’s not a sustainable model. So can we synthesise safer design materials? Can we derive materials from food waste as part of the circular economy and turn them into useful materials that we can use to address this problem?”

This is low-hanging fruit for the field of nanotechnology, Demokritou said, and as research into materials gets better so will the multi-pronged approach of substituting plastic in our daily lives and filtering out its microplastic residue from the environment.

“But there’s a big distinction between an invention and an innovation,” Demokritou said. “Invention is something that nobody has thought about yet. Right? But innovation is something that will change people’s lives, because it makes it to commercialisation, and it can be scaled.”

Gel that repairs heart attack damage could improve health of millions

Injectable, biodegradable technology developed by UK team works as a scaffold to help new tissue grow

Andrew Gregory Health editor

the guardian

Tue 7 Jun 2022 19.01 EDT

British researchers have developed a biodegradable gel to repair damage caused by a heart attack in a breakthrough that could improve the health of millions of survivors worldwide.

There are more than 100,000 hospital admissions every year due to heart attacks in the UK alone – one every five minutes. Medical advances mean more people than ever before survive, with 1.4 million Britons alive today after experiencing a heart attack. But hearts have a very limited ability to regenerate, meaning survivors are left at risk of heart failure and other health problems.

Now after years of efforts searching for solutions to help the heart repair itself, researchers at the University of Manchester have created a gel that can be injected directly into the beating heart – effectively working as a scaffold to help injected cells grow new tissue.

Until now, when cells have been injected into the heart to reduce the risk of heart failure, only 1% have stayed in place and survived. But the gel can hold them in place as they graft on to the heart.

“While it’s still early days, the potential this new technology has in helping to repair failing hearts after a heart attack is huge,” said Katharine King, who led the research backed by the British Heart Foundation (BHF). “We’re confident that this gel will be an effective option for future cell-based therapies to help the damaged heart to regenerate.

To prove the technology could work, researchers showed the gel can support growth of normal heart muscle tissue. When they added human cells reprogrammed to become heart muscle cells into the gel, they were able to grow in a dish for three weeks and the cells started to spontaneously beat.

Echocardiograms (ultrasounds of the heart) and electrocardiograms (ECGs, which measure the electrical activity of the heart) on mice confirmed the safety of the gel. To gain more knowledge, researchers will test the gel after mice have a heart attack to show they develop new muscle tissue.

The study is being presented at the British Cardiovascular Society conference in Manchester.

Prof James Leiper, an associate medical director at the BHF, said: “We’ve come so far in our ability to treat heart attacks and today more people than ever survive. However, this also means that more people are surviving with damaged hearts and are at risk of developing heart failure.

“This new injectable technology harnesses the natural properties of peptides to potentially solve one of the problems that has hindered this type of therapy for years. If the benefits are replicated in further research and then in patients, these gels could become a significant component of future treatments to repair the damage caused by heart attacks.”

Separate research being presented at the same conference found that obesity can drive hearts to fail and weaken their structure.

The largest study of its kind on 490,000 people found that those with a higher body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio had about a 30% increased risk of heart failure. This risk occurred regardless of other risks for heart failure such as diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Dr Zahra Raisi-Estabragh, from Queen Mary University of London, who supervised the study, said: “We already know that obesity increases the risk of heart and circulatory diseases that can go on to cause heart failure. But now we have revealed that obesity itself could be a driver of hearts starting to fail.”

There are more than 100,000 hospital admissions every year due to heart attacks in the UK alone – one every five minutes. Medical advances mean more people than ever before survive, with 1.4 million Britons alive today after experiencing a heart attack. But hearts have a very limited ability to regenerate, meaning survivors are left at risk of heart failure and other health problems.

Now after years of efforts searching for solutions to help the heart repair itself, researchers at the University of Manchester have created a gel that can be injected directly into the beating heart – effectively working as a scaffold to help injected cells grow new tissue.

Until now, when cells have been injected into the heart to reduce the risk of heart failure, only 1% have stayed in place and survived. But the gel can hold them in place as they graft on to the heart.

“While it’s still early days, the potential this new technology has in helping to repair failing hearts after a heart attack is huge,” said Katharine King, who led the research backed by the British Heart Foundation (BHF). “We’re confident that this gel will be an effective option for future cell-based therapies to help the damaged heart to regenerate.

To prove the technology could work, researchers showed the gel can support growth of normal heart muscle tissue. When they added human cells reprogrammed to become heart muscle cells into the gel, they were able to grow in a dish for three weeks and the cells started to spontaneously beat.

Echocardiograms (ultrasounds of the heart) and electrocardiograms (ECGs, which measure the electrical activity of the heart) on mice confirmed the safety of the gel. To gain more knowledge, researchers will test the gel after mice have a heart attack to show they develop new muscle tissue.

The study is being presented at the British Cardiovascular Society conference in Manchester.

Prof James Leiper, an associate medical director at the BHF, said: “We’ve come so far in our ability to treat heart attacks and today more people than ever survive. However, this also means that more people are surviving with damaged hearts and are at risk of developing heart failure.

“This new injectable technology harnesses the natural properties of peptides to potentially solve one of the problems that has hindered this type of therapy for years. If the benefits are replicated in further research and then in patients, these gels could become a significant component of future treatments to repair the damage caused by heart attacks.”

Separate research being presented at the same conference found that obesity can drive hearts to fail and weaken their structure.

The largest study of its kind on 490,000 people found that those with a higher body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio had about a 30% increased risk of heart failure. This risk occurred regardless of other risks for heart failure such as diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Dr Zahra Raisi-Estabragh, from Queen Mary University of London, who supervised the study, said: “We already know that obesity increases the risk of heart and circulatory diseases that can go on to cause heart failure. But now we have revealed that obesity itself could be a driver of hearts starting to fail.”

Study suggests bacteria in cow’s stomach can break down plastic

Scientists find micro-organisms from the bovine stomach have ability to degrade polyesters in lab setting

Natalie Grover

the guardian

Fri 2 Jul 2021 05.14 EDT

Bacteria found in one of the compartments of a cow’s stomach can break down plastic, research suggests.

Since the 1950s, more than 8bn tonnes of plastic have been produced – equivalent in weight to 1 billion elephants – driven predominantly by packaging, single-use containers, wrapping and bottles. As a result, plastic pollution is all-pervasive, in the water and in the air, with people unwittingly consuming and breathing microplastic particles. In recent years, researchers have been working on harnessing the ability of tiny microscopic bugs to break down the stubborn material.

There are existing microbes that are able to degrade natural polyester, found for example in the peels of tomatoes or apples. Given that cow diets contain these natural polyesters, scientists suspected the bovine stomach would contain a cornucopia of microbes to degrade all the plant material.

To test that theory, Dr Doris Ribitsch, of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, and her colleagues procured liquid from the rumen, a compartment of a cow’s stomach, from a slaughterhouse in Austria. One cow typically produces a rumen volume of about 100 litres, noted Ribitsch. “You can imagine the huge amount of rumen liquid accumulating in slaughterhouses every day – and it’s only waste.”

That liquid was incubated with the three types of polyesters – PET (a synthetic polymer commonly used in textiles and packaging); PBAT (biodegradable plastic often used in compostable plastic bags); and PEF (a biobased material made from renewable resources). Each plastic was tested in both film and powder form.

The results showed all three plastics could be broken down by the micro-organisms from cow stomachs in the lab setting, with the plastic powders breaking down quicker than plastic film. The next steps, she said, were to identify those microbes crucial to plastic degradation from the thousands present in the rumen, and then the enzymes produced by them. Once the enzymes have been identified, they can be produced and applied in recycling plants.

For now, plastic waste is mostly burned. To a lesser extent, it is melted for use in other products, but beyond a point it becomes damaged and can no longer be used again. Another method is chemical recycling – turning plastic waste back into base chemicals – but that is not an environmentally friendly process. Using enzymes is billed as a form of green chemical recycling.

Other researchers are further along in their quest to developing and scaling such enzymes. In September a super-enzyme was engineered by linking two separate enzymes, both of which were found in the plastic-eating bug discovered at a Japanese waste site in 2016.

The researchers revealed an engineered version of the first enzyme in 2018, which started breaking down the plastic in a few days. But the super-enzyme gets to work six times faster. Earlier in April, the French company Carbios revealed a different enzyme, originally discovered in a compost heap of leaves, that degrades 90% of plastic bottles within 10 hours.

In the rumen liquid, it appears there is not just one type of enzyme present, but rather different enzymes working together to achieve degradation, the authors suggested in the journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology.

Carbios was working on scaling up its technology, noted Ribitsch. “But of course, it’s always good to have even better enzymes that are maybe recycling other polymers, not only PET, for example … so it can be seen as a general recycling material.”

Since the 1950s, more than 8bn tonnes of plastic have been produced – equivalent in weight to 1 billion elephants – driven predominantly by packaging, single-use containers, wrapping and bottles. As a result, plastic pollution is all-pervasive, in the water and in the air, with people unwittingly consuming and breathing microplastic particles. In recent years, researchers have been working on harnessing the ability of tiny microscopic bugs to break down the stubborn material.

There are existing microbes that are able to degrade natural polyester, found for example in the peels of tomatoes or apples. Given that cow diets contain these natural polyesters, scientists suspected the bovine stomach would contain a cornucopia of microbes to degrade all the plant material.

To test that theory, Dr Doris Ribitsch, of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna, and her colleagues procured liquid from the rumen, a compartment of a cow’s stomach, from a slaughterhouse in Austria. One cow typically produces a rumen volume of about 100 litres, noted Ribitsch. “You can imagine the huge amount of rumen liquid accumulating in slaughterhouses every day – and it’s only waste.”

That liquid was incubated with the three types of polyesters – PET (a synthetic polymer commonly used in textiles and packaging); PBAT (biodegradable plastic often used in compostable plastic bags); and PEF (a biobased material made from renewable resources). Each plastic was tested in both film and powder form.

The results showed all three plastics could be broken down by the micro-organisms from cow stomachs in the lab setting, with the plastic powders breaking down quicker than plastic film. The next steps, she said, were to identify those microbes crucial to plastic degradation from the thousands present in the rumen, and then the enzymes produced by them. Once the enzymes have been identified, they can be produced and applied in recycling plants.

For now, plastic waste is mostly burned. To a lesser extent, it is melted for use in other products, but beyond a point it becomes damaged and can no longer be used again. Another method is chemical recycling – turning plastic waste back into base chemicals – but that is not an environmentally friendly process. Using enzymes is billed as a form of green chemical recycling.

Other researchers are further along in their quest to developing and scaling such enzymes. In September a super-enzyme was engineered by linking two separate enzymes, both of which were found in the plastic-eating bug discovered at a Japanese waste site in 2016.

The researchers revealed an engineered version of the first enzyme in 2018, which started breaking down the plastic in a few days. But the super-enzyme gets to work six times faster. Earlier in April, the French company Carbios revealed a different enzyme, originally discovered in a compost heap of leaves, that degrades 90% of plastic bottles within 10 hours.

In the rumen liquid, it appears there is not just one type of enzyme present, but rather different enzymes working together to achieve degradation, the authors suggested in the journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology.

Carbios was working on scaling up its technology, noted Ribitsch. “But of course, it’s always good to have even better enzymes that are maybe recycling other polymers, not only PET, for example … so it can be seen as a general recycling material.”

MIT Engineers Have Discovered a Completely New Way of Generating Electricity

By ANNE TRAFTON, MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

scitechdaily.com

JUNE 7, 2021

Tiny Particles Power Chemical Reactions

A new material made from carbon nanotubes can generate electricity by scavenging energy from its environment.

MIT engineers have discovered a new way of generating electricity using tiny carbon particles that can create a current simply by interacting with liquid surrounding them.

The liquid, an organic solvent, draws electrons out of the particles, generating a current that could be used to drive chemical reactions or to power micro- or nanoscale robots, the researchers say.

“This mechanism is new, and this way of generating energy is completely new,” says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT. “This technology is intriguing because all you have to do is flow a solvent through a bed of these particles. This allows you to do electrochemistry, but with no wires.”

In a new study describing this phenomenon, the researchers showed that they could use this electric current to drive a reaction known as alcohol oxidation — an organic chemical reaction that is important in the chemical industry.

Strano is the senior author of the paper, which appears today (June 7, 2021) in Nature Communications. The lead authors of the study are MIT graduate student Albert Tianxiang Liu and former MIT researcher Yuichiro Kunai. Other authors include former graduate student Anton Cottrill, postdocs Amir Kaplan and Hyunah Kim, graduate student Ge Zhang, and recent MIT graduates Rafid Mollah and Yannick Eatmon.

Unique properties

The new discovery grew out of Strano’s research on carbon nanotubes — hollow tubes made of a lattice of carbon atoms, which have unique electrical properties. In 2010, Strano demonstrated, for the first time, that carbon nanotubes can generate “thermopower waves.” When a carbon nanotube is coated with layer of fuel, moving pulses of heat, or thermopower waves, travel along the tube, creating an electrical current.

That work led Strano and his students to uncover a related feature of carbon nanotubes. They found that when part of a nanotube is coated with a Teflon-like polymer, it creates an asymmetry that makes it possible for electrons to flow from the coated to the uncoated part of the tube, generating an electrical current. Those electrons can be drawn out by submerging the particles in a solvent that is hungry for electrons.

To harness this special capability, the researchers created electricity-generating particles by grinding up carbon nanotubes and forming them into a sheet of paper-like material. One side of each sheet was coated with a Teflon-like polymer, and the researchers then cut out small particles, which can be any shape or size. For this study, they made particles that were 250 microns by 250 microns.

When these particles are submerged in an organic solvent such as acetonitrile, the solvent adheres to the uncoated surface of the particles and begins pulling electrons out of them.

“The solvent takes electrons away, and the system tries to equilibrate by moving electrons,” Strano says. “There’s no sophisticated battery chemistry inside. It’s just a particle and you put it into solvent and it starts generating an electric field.”

“This research cleverly shows how to extract the ubiquitous (and often unnoticed) electric energy stored in an electronic material for on-site electrochemical synthesis,” says Jun Yao, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, who was not involved in the study. “The beauty is that it points to a generic methodology that can be readily expanded to the use of different materials and applications in different synthetic systems.”

Particle power

The current version of the particles can generate about 0.7 volts of electricity per particle. In this study, the researchers also showed that they can form arrays of hundreds of particles in a small test tube. This “packed bed” reactor generates enough energy to power a chemical reaction called an alcohol oxidation, in which an alcohol is converted to an aldehyde or a ketone. Usually, this reaction is not performed using electrochemistry because it would require too much external current.

“Because the packed bed reactor is compact, it has more flexibility in terms of applications than a large electrochemical reactor,” Zhang says. “The particles can be made very small, and they don’t require any external wires in order to drive the electrochemical reaction.”

In future work, Strano hopes to use this kind of energy generation to build polymers using only carbon dioxide as a starting material. In a related project, he has already created polymers that can regenerate themselves using carbon dioxide as a building material, in a process powered by solar energy. This work is inspired by carbon fixation, the set of chemical reactions that plants use to build sugars from carbon dioxide, using energy from the sun.

In the longer term, this approach could also be used to power micro- or nanoscale robots. Strano’s lab has already begun building robots at that scale, which could one day be used as diagnostic or environmental sensors. The idea of being able to scavenge energy from the environment to power these kinds of robots is appealing, he says.

“It means you don’t have to put the energy storage on board,” he says. “What we like about this mechanism is that you can take the energy, at least in part, from the environment.”

A new material made from carbon nanotubes can generate electricity by scavenging energy from its environment.

MIT engineers have discovered a new way of generating electricity using tiny carbon particles that can create a current simply by interacting with liquid surrounding them.

The liquid, an organic solvent, draws electrons out of the particles, generating a current that could be used to drive chemical reactions or to power micro- or nanoscale robots, the researchers say.

“This mechanism is new, and this way of generating energy is completely new,” says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT. “This technology is intriguing because all you have to do is flow a solvent through a bed of these particles. This allows you to do electrochemistry, but with no wires.”

In a new study describing this phenomenon, the researchers showed that they could use this electric current to drive a reaction known as alcohol oxidation — an organic chemical reaction that is important in the chemical industry.

Strano is the senior author of the paper, which appears today (June 7, 2021) in Nature Communications. The lead authors of the study are MIT graduate student Albert Tianxiang Liu and former MIT researcher Yuichiro Kunai. Other authors include former graduate student Anton Cottrill, postdocs Amir Kaplan and Hyunah Kim, graduate student Ge Zhang, and recent MIT graduates Rafid Mollah and Yannick Eatmon.

Unique properties

The new discovery grew out of Strano’s research on carbon nanotubes — hollow tubes made of a lattice of carbon atoms, which have unique electrical properties. In 2010, Strano demonstrated, for the first time, that carbon nanotubes can generate “thermopower waves.” When a carbon nanotube is coated with layer of fuel, moving pulses of heat, or thermopower waves, travel along the tube, creating an electrical current.

That work led Strano and his students to uncover a related feature of carbon nanotubes. They found that when part of a nanotube is coated with a Teflon-like polymer, it creates an asymmetry that makes it possible for electrons to flow from the coated to the uncoated part of the tube, generating an electrical current. Those electrons can be drawn out by submerging the particles in a solvent that is hungry for electrons.

To harness this special capability, the researchers created electricity-generating particles by grinding up carbon nanotubes and forming them into a sheet of paper-like material. One side of each sheet was coated with a Teflon-like polymer, and the researchers then cut out small particles, which can be any shape or size. For this study, they made particles that were 250 microns by 250 microns.

When these particles are submerged in an organic solvent such as acetonitrile, the solvent adheres to the uncoated surface of the particles and begins pulling electrons out of them.

“The solvent takes electrons away, and the system tries to equilibrate by moving electrons,” Strano says. “There’s no sophisticated battery chemistry inside. It’s just a particle and you put it into solvent and it starts generating an electric field.”

“This research cleverly shows how to extract the ubiquitous (and often unnoticed) electric energy stored in an electronic material for on-site electrochemical synthesis,” says Jun Yao, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, who was not involved in the study. “The beauty is that it points to a generic methodology that can be readily expanded to the use of different materials and applications in different synthetic systems.”

Particle power

The current version of the particles can generate about 0.7 volts of electricity per particle. In this study, the researchers also showed that they can form arrays of hundreds of particles in a small test tube. This “packed bed” reactor generates enough energy to power a chemical reaction called an alcohol oxidation, in which an alcohol is converted to an aldehyde or a ketone. Usually, this reaction is not performed using electrochemistry because it would require too much external current.

“Because the packed bed reactor is compact, it has more flexibility in terms of applications than a large electrochemical reactor,” Zhang says. “The particles can be made very small, and they don’t require any external wires in order to drive the electrochemical reaction.”

In future work, Strano hopes to use this kind of energy generation to build polymers using only carbon dioxide as a starting material. In a related project, he has already created polymers that can regenerate themselves using carbon dioxide as a building material, in a process powered by solar energy. This work is inspired by carbon fixation, the set of chemical reactions that plants use to build sugars from carbon dioxide, using energy from the sun.

In the longer term, this approach could also be used to power micro- or nanoscale robots. Strano’s lab has already begun building robots at that scale, which could one day be used as diagnostic or environmental sensors. The idea of being able to scavenge energy from the environment to power these kinds of robots is appealing, he says.

“It means you don’t have to put the energy storage on board,” he says. “What we like about this mechanism is that you can take the energy, at least in part, from the environment.”

Astronomy

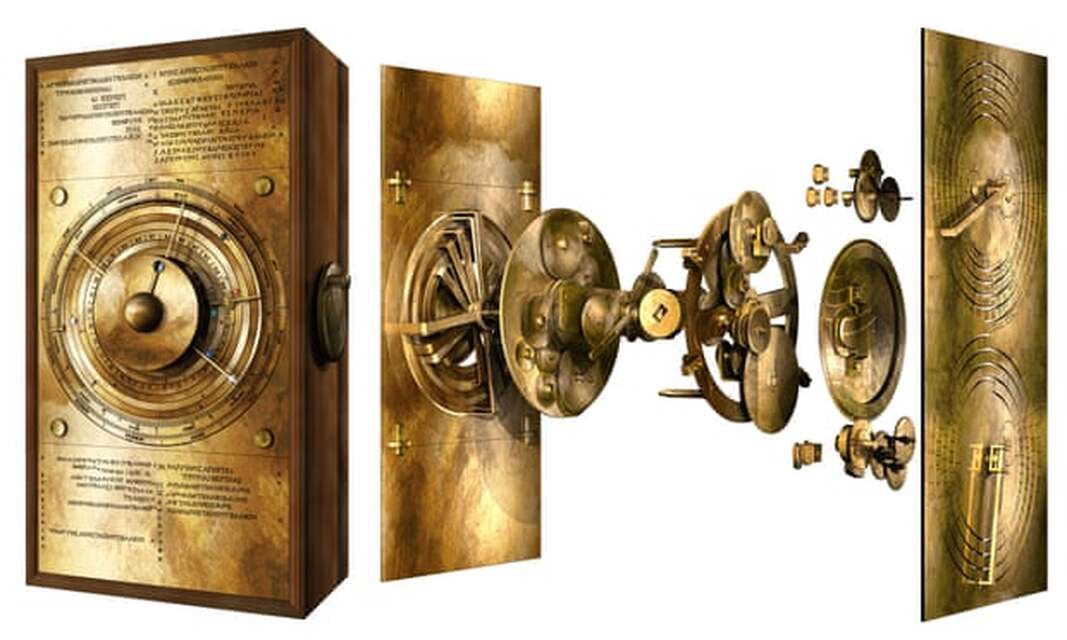

Scientists may have solved ancient mystery of 'first computer'

Researchers claim breakthrough in study of 2,000-year-old Antikythera mechanism, an astronomical calculator found in sea

Ian Sample Science editor

the guardian

Fri 12 Mar 2021 05.00 EST

From the moment it was discovered more than a century ago, scholars have puzzled over the Antikythera mechanism, a remarkable and baffling astronomical calculator that survives from the ancient world.

The hand-powered, 2,000-year-old device displayed the motion of the universe, predicting the movement of the five known planets, the phases of the moon and the solar and lunar eclipses. But quite how it achieved such impressive feats has proved fiendishly hard to untangle.

Now researchers at UCL believe they have solved the mystery – at least in part – and have set about reconstructing the device, gearwheels and all, to test whether their proposal works. If they can build a replica with modern machinery, they aim to do the same with techniques from antiquity.

“We believe that our reconstruction fits all the evidence that scientists have gleaned from the extant remains to date,” said Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL. While other scholars have made reconstructions in the past, the fact that two-thirds of the mechanism are missing has made it hard to know for sure how it worked.

The mechanism, often described as the world’s first analogue computer, was found by sponge divers in 1901 amid a haul of treasures salvaged from a merchant ship that met with disaster off the Greek island of Antikythera. The ship is believed to have foundered in a storm in the first century BC as it passed between Crete and the Peloponnese en route to Rome from Asia Minor.

The battered fragments of corroded brass were barely noticed at first, but decades of scholarly work have revealed the object to be a masterpiece of mechanical engineering. Originally encased in a wooden box one foot tall, the mechanism was covered in inscriptions – a built-in user’s manual – and contained more than 30 bronze gearwheels connected to dials and pointers. Turn the handle and the heavens, as known to the Greeks, swung into motion.

Michael Wright, a former curator of mechanical engineering at the Science Museum in London, pieced together much of how the mechanism operated and built a working replica, but researchers have never had a complete understanding of how the device functioned. Their efforts have not been helped by the remnants surviving in 82 separate fragments, making the task of rebuilding it equivalent to solving a battered 3D puzzle that has most of its pieces missing.

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, the UCL team describe how they drew on the work of Wright and others, and used inscriptions on the mechanism and a mathematical method described by the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides, to work out new gear arrangements that would move the planets and other bodies in the correct way. The solution allows nearly all of the mechanism’s gearwheels to fit within a space only 25mm deep.

According to the team, the mechanism may have displayed the movement of the sun, moon and the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn on concentric rings. Because the device assumed that the sun and planets revolved around Earth, their paths were far more difficult to reproduce with gearwheels than if the sun was placed at the centre. Another change the scientists propose is a double-ended pointer they call a “Dragon Hand” that indicates when eclipses are due to happen.

The researchers believe the work brings them closer to a true understanding of how the Antikythera device displayed the heavens, but it is not clear whether the design is correct or could have been built with ancient manufacturing techniques. The concentric rings that make up the display would need to rotate on a set of nested, hollow axles, but without a lathe to shape the metal, it is unclear how the ancient Greeks would have manufactured such components.

“The concentric tubes at the core of the planetarium are where my faith in Greek tech falters, and where the model might also falter,” said Wojcik. “Lathes would be the way today, but we can’t assume they had those for metal.”

Whether or not the model works, more mysteries remain. It is unclear whether the Antikythera mechanism was a toy, a teaching tool or had some other purpose. And if the ancient Greeks were capable of such mechanical devices, what else did they do with the knowledge?

“Although metal is precious, and so would have been recycled, it is odd that nothing remotely similar has been found or dug up,” Wojcik said. “If they had the tech to make the Antikythera mechanism, why did they not extend this tech to devising other machines, such as clocks?”

The hand-powered, 2,000-year-old device displayed the motion of the universe, predicting the movement of the five known planets, the phases of the moon and the solar and lunar eclipses. But quite how it achieved such impressive feats has proved fiendishly hard to untangle.

Now researchers at UCL believe they have solved the mystery – at least in part – and have set about reconstructing the device, gearwheels and all, to test whether their proposal works. If they can build a replica with modern machinery, they aim to do the same with techniques from antiquity.

“We believe that our reconstruction fits all the evidence that scientists have gleaned from the extant remains to date,” said Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL. While other scholars have made reconstructions in the past, the fact that two-thirds of the mechanism are missing has made it hard to know for sure how it worked.

The mechanism, often described as the world’s first analogue computer, was found by sponge divers in 1901 amid a haul of treasures salvaged from a merchant ship that met with disaster off the Greek island of Antikythera. The ship is believed to have foundered in a storm in the first century BC as it passed between Crete and the Peloponnese en route to Rome from Asia Minor.

The battered fragments of corroded brass were barely noticed at first, but decades of scholarly work have revealed the object to be a masterpiece of mechanical engineering. Originally encased in a wooden box one foot tall, the mechanism was covered in inscriptions – a built-in user’s manual – and contained more than 30 bronze gearwheels connected to dials and pointers. Turn the handle and the heavens, as known to the Greeks, swung into motion.

Michael Wright, a former curator of mechanical engineering at the Science Museum in London, pieced together much of how the mechanism operated and built a working replica, but researchers have never had a complete understanding of how the device functioned. Their efforts have not been helped by the remnants surviving in 82 separate fragments, making the task of rebuilding it equivalent to solving a battered 3D puzzle that has most of its pieces missing.

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, the UCL team describe how they drew on the work of Wright and others, and used inscriptions on the mechanism and a mathematical method described by the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides, to work out new gear arrangements that would move the planets and other bodies in the correct way. The solution allows nearly all of the mechanism’s gearwheels to fit within a space only 25mm deep.

According to the team, the mechanism may have displayed the movement of the sun, moon and the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn on concentric rings. Because the device assumed that the sun and planets revolved around Earth, their paths were far more difficult to reproduce with gearwheels than if the sun was placed at the centre. Another change the scientists propose is a double-ended pointer they call a “Dragon Hand” that indicates when eclipses are due to happen.

The researchers believe the work brings them closer to a true understanding of how the Antikythera device displayed the heavens, but it is not clear whether the design is correct or could have been built with ancient manufacturing techniques. The concentric rings that make up the display would need to rotate on a set of nested, hollow axles, but without a lathe to shape the metal, it is unclear how the ancient Greeks would have manufactured such components.

“The concentric tubes at the core of the planetarium are where my faith in Greek tech falters, and where the model might also falter,” said Wojcik. “Lathes would be the way today, but we can’t assume they had those for metal.”

Whether or not the model works, more mysteries remain. It is unclear whether the Antikythera mechanism was a toy, a teaching tool or had some other purpose. And if the ancient Greeks were capable of such mechanical devices, what else did they do with the knowledge?

“Although metal is precious, and so would have been recycled, it is odd that nothing remotely similar has been found or dug up,” Wojcik said. “If they had the tech to make the Antikythera mechanism, why did they not extend this tech to devising other machines, such as clocks?”

The search for dark matter gets a speed boost from quantum technology

the conservation

February 10, 2021 11.10am EST

Nearly a century after dark matter was first proposed to explain the motion of galaxy clusters, physicists still have no idea what it’s made of.

Researchers around the world have built dozens of detectors in hopes of discovering dark matter. As a graduate student, I helped design and operate one of these detectors, aptly named HAYSTAC. But despite decades of experimental effort, scientists have yet to identify the dark matter particle.

Now, the search for dark matter has received an unlikely assist from technology used in quantum computing research. In a new paper published in the journal Nature, my colleagues on the HAYSTAC team and I describe how we used a bit of quantum trickery to double the rate at which our detector can search for dark matter. Our result adds a much-needed speed boost to the hunt for this mysterious particle.

Scanning for a dark matter signal

There is compelling evidence from astrophysics and cosmology that an unknown substance called dark matter constitutes more than 80% of the matter in the universe. Theoretical physicists have proposed dozens of new fundamental particles that could explain dark matter. But to determine which – if any – of these theories is correct, researchers need to build different detectors to test each one.

One prominent theory proposes that dark matter is made of as-yet hypothetical particles called axions that collectively behave like an invisible wave oscillating at a very specific frequency through the cosmos. Axion detectors – including HAYSTAC – work something like radio receivers, but instead of converting radio waves to sound waves, they aim to convert axion waves into electromagnetic waves. Specifically, axion detectors measure two quantities called electromagnetic field quadratures. These quadratures are two distinct kinds of oscillation in the electromagnetic wave that would be produced if axions exist.

The main challenge in the search for axions is that nobody knows the frequency of the hypothetical axion wave. Imagine you’re in an unfamiliar city searching for a particular radio station by working your way through the FM band one frequency at a time. Axion hunters do much the same thing: They tune their detectors over a wide range of frequencies in discrete steps. Each step can cover only a very small range of possible axion frequencies. This small range is the bandwidth of the detector.

Tuning a radio typically involves pausing for a few seconds at each step to see if you’ve found the station you’re looking for. That’s harder if the signal is weak and there’s a lot of static. An axion signal – in even the most sensitive detectors – would be extraordinarily faint compared with static from random electromagnetic fluctuations, which physicists call noise. The more noise there is, the longer the detector must sit at each tuning step to listen for an axion signal.

Unfortunately, researchers can’t count on picking up the axion broadcast after a few dozen turns of the radio dial. An FM radio tunes from only 88 to 108 megahertz (one megahertz is one million hertz). The axion frequency, by contrast, may be anywhere between 300 hertz and 300 billion hertz. At the rate today’s detectors are going, finding the axion or proving that it doesn’t exist could take more than 10,000 years.

Squeezing the quantum noise

On the HAYSTAC team, we don’t have that kind of patience. So in 2012 we set out to speed up the axion search by doing everything possible to reduce noise. But by 2017 we found ourselves running up against a fundamental minimum noise limit because of a law of quantum physics known as the uncertainty principle.

The uncertainty principle states that it is impossible to know the exact values of certain physical quantities simultaneously – for instance, you can’t know both the position and the momentum of a particle at the same time. Recall that axion detectors search for the axion by measuring two quadratures – those specific kinds of electromagnetic field oscillations. The uncertainty principle prohibits precise knowledge of both quadratures by adding a minimum amount of noise to the quadrature oscillations.

In conventional axion detectors, the quantum noise from the uncertainty principle obscures both quadratures equally. This noise can’t be eliminated, but with the right tools it can be controlled. Our team worked out a way to shuffle around the quantum noise in the HAYSTAC detector, reducing its effect on one quadrature while increasing its effect on the other. This noise manipulation technique is called quantum squeezing.

In an effort led by graduate students Kelly Backes and Dan Palken, the HAYSTAC team took on the challenge of implementing squeezing in our detector, using superconducting circuit technology borrowed from quantum computing research. General-purpose quantum computers remain a long way off, but our new paper shows that this squeezing technology can immediately speed up the search for dark matter.

Bigger bandwidth, faster search

Our team succeeded in squeezing the noise in the HAYSTAC detector. But how did we use this to speed up the axion search?

Quantum squeezing doesn’t reduce the noise uniformly across the axion detector bandwidth. Instead, it has the largest effect at the edges. Imagine you tune your radio to 88.3 megahertz, but the station you want is actually at 88.1. With quantum squeezing, you would be able to hear your favorite song playing one station away.

In the world of radio broadcasting this would be a recipe for disaster, because different stations would interfere with one another. But with only one dark matter signal to look for, a wider bandwidth allows physicists to search faster by covering more frequencies at once. In our latest result we used squeezing to double the bandwidth of HAYSTAC, allowing us to search for axions twice as fast as we could before.

Quantum squeezing alone isn’t enough to scan through every possible axion frequency in a reasonable time. But doubling the scan rate is a big step in the right direction, and we believe further improvements to our quantum squeezing system may enable us to scan 10 times faster.

Nobody knows whether axions exist or whether they will resolve the mystery of dark matter; but thanks to this unexpected application of quantum technology, we’re one step closer to answering these questions.

Researchers around the world have built dozens of detectors in hopes of discovering dark matter. As a graduate student, I helped design and operate one of these detectors, aptly named HAYSTAC. But despite decades of experimental effort, scientists have yet to identify the dark matter particle.

Now, the search for dark matter has received an unlikely assist from technology used in quantum computing research. In a new paper published in the journal Nature, my colleagues on the HAYSTAC team and I describe how we used a bit of quantum trickery to double the rate at which our detector can search for dark matter. Our result adds a much-needed speed boost to the hunt for this mysterious particle.

Scanning for a dark matter signal

There is compelling evidence from astrophysics and cosmology that an unknown substance called dark matter constitutes more than 80% of the matter in the universe. Theoretical physicists have proposed dozens of new fundamental particles that could explain dark matter. But to determine which – if any – of these theories is correct, researchers need to build different detectors to test each one.

One prominent theory proposes that dark matter is made of as-yet hypothetical particles called axions that collectively behave like an invisible wave oscillating at a very specific frequency through the cosmos. Axion detectors – including HAYSTAC – work something like radio receivers, but instead of converting radio waves to sound waves, they aim to convert axion waves into electromagnetic waves. Specifically, axion detectors measure two quantities called electromagnetic field quadratures. These quadratures are two distinct kinds of oscillation in the electromagnetic wave that would be produced if axions exist.

The main challenge in the search for axions is that nobody knows the frequency of the hypothetical axion wave. Imagine you’re in an unfamiliar city searching for a particular radio station by working your way through the FM band one frequency at a time. Axion hunters do much the same thing: They tune their detectors over a wide range of frequencies in discrete steps. Each step can cover only a very small range of possible axion frequencies. This small range is the bandwidth of the detector.

Tuning a radio typically involves pausing for a few seconds at each step to see if you’ve found the station you’re looking for. That’s harder if the signal is weak and there’s a lot of static. An axion signal – in even the most sensitive detectors – would be extraordinarily faint compared with static from random electromagnetic fluctuations, which physicists call noise. The more noise there is, the longer the detector must sit at each tuning step to listen for an axion signal.

Unfortunately, researchers can’t count on picking up the axion broadcast after a few dozen turns of the radio dial. An FM radio tunes from only 88 to 108 megahertz (one megahertz is one million hertz). The axion frequency, by contrast, may be anywhere between 300 hertz and 300 billion hertz. At the rate today’s detectors are going, finding the axion or proving that it doesn’t exist could take more than 10,000 years.

Squeezing the quantum noise

On the HAYSTAC team, we don’t have that kind of patience. So in 2012 we set out to speed up the axion search by doing everything possible to reduce noise. But by 2017 we found ourselves running up against a fundamental minimum noise limit because of a law of quantum physics known as the uncertainty principle.

The uncertainty principle states that it is impossible to know the exact values of certain physical quantities simultaneously – for instance, you can’t know both the position and the momentum of a particle at the same time. Recall that axion detectors search for the axion by measuring two quadratures – those specific kinds of electromagnetic field oscillations. The uncertainty principle prohibits precise knowledge of both quadratures by adding a minimum amount of noise to the quadrature oscillations.

In conventional axion detectors, the quantum noise from the uncertainty principle obscures both quadratures equally. This noise can’t be eliminated, but with the right tools it can be controlled. Our team worked out a way to shuffle around the quantum noise in the HAYSTAC detector, reducing its effect on one quadrature while increasing its effect on the other. This noise manipulation technique is called quantum squeezing.

In an effort led by graduate students Kelly Backes and Dan Palken, the HAYSTAC team took on the challenge of implementing squeezing in our detector, using superconducting circuit technology borrowed from quantum computing research. General-purpose quantum computers remain a long way off, but our new paper shows that this squeezing technology can immediately speed up the search for dark matter.

Bigger bandwidth, faster search

Our team succeeded in squeezing the noise in the HAYSTAC detector. But how did we use this to speed up the axion search?

Quantum squeezing doesn’t reduce the noise uniformly across the axion detector bandwidth. Instead, it has the largest effect at the edges. Imagine you tune your radio to 88.3 megahertz, but the station you want is actually at 88.1. With quantum squeezing, you would be able to hear your favorite song playing one station away.

In the world of radio broadcasting this would be a recipe for disaster, because different stations would interfere with one another. But with only one dark matter signal to look for, a wider bandwidth allows physicists to search faster by covering more frequencies at once. In our latest result we used squeezing to double the bandwidth of HAYSTAC, allowing us to search for axions twice as fast as we could before.

Quantum squeezing alone isn’t enough to scan through every possible axion frequency in a reasonable time. But doubling the scan rate is a big step in the right direction, and we believe further improvements to our quantum squeezing system may enable us to scan 10 times faster.

Nobody knows whether axions exist or whether they will resolve the mystery of dark matter; but thanks to this unexpected application of quantum technology, we’re one step closer to answering these questions.

DeepMind AI cracks 50-year-old problem of protein folding

Program solves scientific problem in ‘stunning advance’ for understanding machinery of life

Ian Sample Science editor

the guardian

Mon 30 Nov 2020 10.58 EST

Having risen to fame on its superhuman performance at playing games, the artificial intelligence group DeepMind has cracked a serious scientific problem that has stumped researchers for half a century.

With its latest AI program, AlphaFold, the company and research laboratory showed it can predict how proteins fold into 3D shapes, a fiendishly complex process that is fundamental to understanding the biological machinery of life.

Independent scientists said the breakthrough would help researchers tease apart the mechanisms that drive some diseases and pave the way for designer medicines, more nutritious crops and “green enzymes” that can break down plastic pollution.

DeepMind said it had started work with a handful of scientific groups and would focus initially on malaria, sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease.

“It marks an exciting moment for the field,” said Demis Hassabis, DeepMind’s founder and chief executive. “These algorithms are now becoming mature enough and powerful enough to be applicable to really challenging scientific problems.”

Venki Ramakrishnan, the president of the Royal Society, called the work “a stunning advance” that had occurred “decades before many people in the field would have predicted”.

DeepMind is best known for its run of human-trouncing programs that achieved supremacy in chess, Go, Starcraft II and old-school Atari classics. But superhuman gameplay was never the primary aim. Instead, games provided a training ground for programs that, once powerful enough, would be unleashed on real-world problems.

Protein folding has been a grand challenge in biology for 50 years. An arcane form of molecular origami, its importance is hard to overstate. Most biological processes revolve around proteins and a protein’s shape determines its function. When researchers know how a protein folds up, they can start to uncover what it does. How insulin controls sugar levels in the blood and how antibodies fight coronavirus are both determined by protein structure.

Scientists have identified more than 200m proteins but structures are known for only a fraction of them. Traditionally, the shapes are discovered through meticulous lab work that can take years. And while computer scientists have made headway on the problem, inferring the structure from a protein’s makeup is no easy task. Proteins are chains of amino acids that can twist and bend into a mind-boggling variety of shapes: a googol cubed, or 1 followed by 300 zeroes.

To learn how proteins fold, researchers at DeepMind trained their algorithm on a public database containing about 170,000 protein sequences and their shapes. Running on the equivalent of 100 to 200 graphics processing units – by modern standards, a modest amount of computing power – the training took a few weeks.

DeepMind put AlphaFold through its paces by entering it for a biennial “protein olympics” known as Casp, the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction. Entrants to the international competition are given the amino acid sequences for about 100 proteins and challenged to work them out. The results from teams that use computers are compared with those based on lab work.

AlphaFold not only outperformed other computer programs but reached an accuracy comparable to the laborious and time-consuming lab-based methods. When ranked across all proteins analysed, AlphaFold had a median score of 92.5 out of 100, with 90 being the equivalent to experimental methods. For the hardest proteins, the median score fell, but only marginally to 87.

Hassabis said DeepMind had started work on how to give researchers access to AlphaFold to help with scientific research. Andrei Lupas, the director of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, Germany, said he had already used the program to solve a protein structure that scientists had been stuck on for a decade.

Janet Thornton, a director emeritus of EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute near Cambridge, who was not involved in the work, said she was excited to hear the results. “This is a problem that I was beginning to think would not get solved in my lifetime,” she said. “Knowing these structures will really help us to understand how human beings operate and function, how we work.”

John Jumper, a researcher on the team at DeepMind, said: “We really didn’t know until we saw the Casp results how far we had pushed the field.” It is not the end of the work, however. Future research will focus on how proteins combine to form larger “complexes” and how they interact with other molecules in living organisms.

With its latest AI program, AlphaFold, the company and research laboratory showed it can predict how proteins fold into 3D shapes, a fiendishly complex process that is fundamental to understanding the biological machinery of life.

Independent scientists said the breakthrough would help researchers tease apart the mechanisms that drive some diseases and pave the way for designer medicines, more nutritious crops and “green enzymes” that can break down plastic pollution.

DeepMind said it had started work with a handful of scientific groups and would focus initially on malaria, sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease.

“It marks an exciting moment for the field,” said Demis Hassabis, DeepMind’s founder and chief executive. “These algorithms are now becoming mature enough and powerful enough to be applicable to really challenging scientific problems.”

Venki Ramakrishnan, the president of the Royal Society, called the work “a stunning advance” that had occurred “decades before many people in the field would have predicted”.

DeepMind is best known for its run of human-trouncing programs that achieved supremacy in chess, Go, Starcraft II and old-school Atari classics. But superhuman gameplay was never the primary aim. Instead, games provided a training ground for programs that, once powerful enough, would be unleashed on real-world problems.

Protein folding has been a grand challenge in biology for 50 years. An arcane form of molecular origami, its importance is hard to overstate. Most biological processes revolve around proteins and a protein’s shape determines its function. When researchers know how a protein folds up, they can start to uncover what it does. How insulin controls sugar levels in the blood and how antibodies fight coronavirus are both determined by protein structure.

Scientists have identified more than 200m proteins but structures are known for only a fraction of them. Traditionally, the shapes are discovered through meticulous lab work that can take years. And while computer scientists have made headway on the problem, inferring the structure from a protein’s makeup is no easy task. Proteins are chains of amino acids that can twist and bend into a mind-boggling variety of shapes: a googol cubed, or 1 followed by 300 zeroes.

To learn how proteins fold, researchers at DeepMind trained their algorithm on a public database containing about 170,000 protein sequences and their shapes. Running on the equivalent of 100 to 200 graphics processing units – by modern standards, a modest amount of computing power – the training took a few weeks.

DeepMind put AlphaFold through its paces by entering it for a biennial “protein olympics” known as Casp, the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction. Entrants to the international competition are given the amino acid sequences for about 100 proteins and challenged to work them out. The results from teams that use computers are compared with those based on lab work.

AlphaFold not only outperformed other computer programs but reached an accuracy comparable to the laborious and time-consuming lab-based methods. When ranked across all proteins analysed, AlphaFold had a median score of 92.5 out of 100, with 90 being the equivalent to experimental methods. For the hardest proteins, the median score fell, but only marginally to 87.

Hassabis said DeepMind had started work on how to give researchers access to AlphaFold to help with scientific research. Andrei Lupas, the director of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, Germany, said he had already used the program to solve a protein structure that scientists had been stuck on for a decade.

Janet Thornton, a director emeritus of EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute near Cambridge, who was not involved in the work, said she was excited to hear the results. “This is a problem that I was beginning to think would not get solved in my lifetime,” she said. “Knowing these structures will really help us to understand how human beings operate and function, how we work.”

John Jumper, a researcher on the team at DeepMind, said: “We really didn’t know until we saw the Casp results how far we had pushed the field.” It is not the end of the work, however. Future research will focus on how proteins combine to form larger “complexes” and how they interact with other molecules in living organisms.

Plastics

New super-enzyme eats plastic bottles six times faster

Breakthrough that builds on plastic-eating bugs first discovered by Japan in 2016 promises to enable full recycling

Damian Carrington Environment editor

THE GUARDIAN

Mon 28 Sep 2020 15.38 EDT

A super-enzyme that degrades plastic bottles six times faster than before has been created by scientists and could be used for recycling within a year or two.

The super-enzyme, derived from bacteria that naturally evolved the ability to eat plastic, enables the full recycling of the bottles. Scientists believe combining it with enzymes that break down cotton could also allow mixed-fabric clothing to be recycled. Today, millions of tonnes of such clothing is either dumped in landfill or incinerated.

Plastic pollution has contaminated the whole planet, from the Arctic to the deepest oceans, and people are now known to consume and breathe microplastic particles. It is currently very difficult to break down plastic bottles into their chemical constituents in order to make new ones from old, meaning more new plastic is being created from oil each year.

The super-enzyme was engineered by linking two separate enzymes, both of which were found in the plastic-eating bug discovered at a Japanese waste site in 2016. The researchers revealed an engineered version of the first enzyme in 2018, which started breaking down the plastic in a few days. But the super-enzyme gets to work six times faster.

“When we linked the enzymes, rather unexpectedly, we got a dramatic increase in activity,“ said Prof John McGeehan, at the University of Portsmouth, UK. “This is a trajectory towards trying to make faster enzymes that are more industrially relevant. But it’s also one of those stories about learning from nature, and then bringing it into the lab.”

French company Carbios revealed a different enzyme in April, originally discovered in a compost heap of leaves, that degrades 90% of plastic bottles within 10 hours, but requires heating above 70C.

The new super-enzyme works at room temperature, and McGeehan said combining different approaches could speed progress towards commercial use: “If we can make better, faster enzymes by linking them together and provide them to companies like Carbios, and work in partnership, we could start doing this within the next year or two.”