welcome to history

page 2

history you should know

**U.S. GUILTY OF MORE ELECTION MEDDLING THAN RUSSIA, HAS DONE TO OTHER COUNTRIES FOR OVER A CENTURY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*COARD: AMERICA'S 12 SLAVEHOLDING PRESIDENTS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A historian explains why Robert E. Lee wasn’t a hero — he was a traitor

(ARTICLE BELOW)

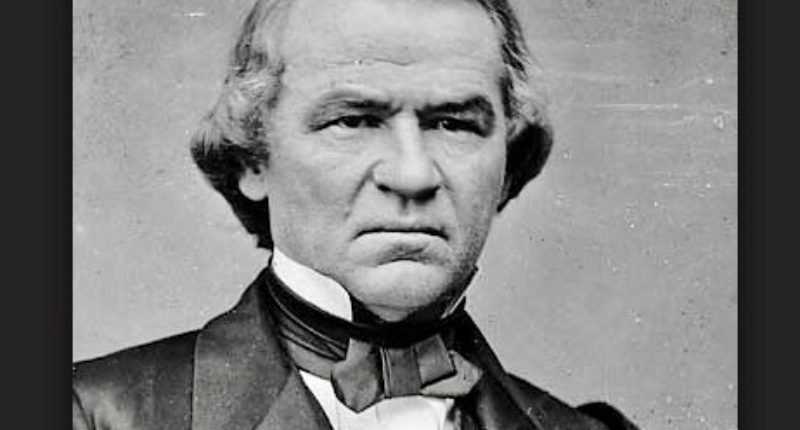

*ANDREW JOHNSON’S FAILED PRESIDENCY ECHOES IN TRUMP’S WHITE HOUSE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ON ITS HUNDREDTH BIRTHDAY IN 1959, EDWARD TELLER WARNED THE OIL INDUSTRY ABOUT GLOBAL WARMING(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WHITE NEWSPAPER JOURNALISTS EXPLOITED RACIAL DIVISIONS TO HELP BUILD THE GOP’S SOUTHERN FIREWALL IN THE 1960S(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE TWO MEN WHO ALMOST DERAILED NEW ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONIES

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*UNITED DAUGHTERS OF THE CONFEDERACY LED A CAMPAIGN TO BUILD MONUMENTS AND WHITEWASH HISTORY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*HOW THE US GOVERNMENT CREATED AND CODDLED THE GUN INDUSTRY

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A HISTORIAN DESTROYS RACISTS’ FAVORITE MYTHS ABOUT THE VIKINGS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*DONALD TRUMP, JEWS AND THE MYTH OF RACE: HOW JEWS GRADUALLY BECAME “WHITE,” AND HOW THAT CHANGED AMERICA(ARTICLE BELOW)

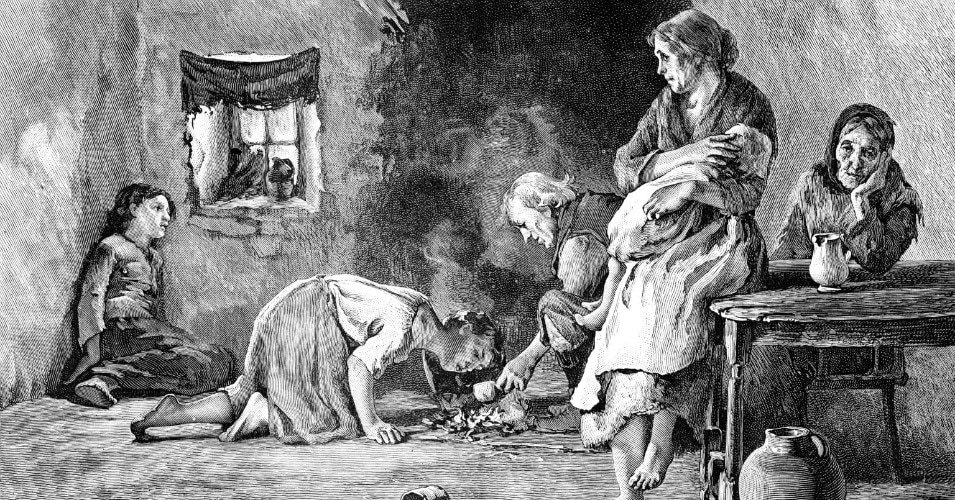

*THE REAL IRISH-AMERICAN STORY NOT TAUGHT IN SCHOOLS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*ROE V. WADE

ABORTION WAS OUTLAWED SO DOCTORS COULD MAKE MONEY(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CHOMSKY ON AMERICA'S UGLY HISTORY: FDR WAS FASCIST-FRIENDLY BEFORE WWII(ARTICLE BELOW)

*HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF CAPITALISM AND IMPERIALISM(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WHY ALLEN DULLES KILLED THE KENNEDYS (ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE REAL (DESPICABLE) THOMAS JEFFERSON(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE SECRET HISTORY OF HITLER’S ‘BLACK HOLOCAUST’(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AND SLAVERY IN A GLOBAL ECONOMY(ARTICLE BELOW)

U.S. Guilty of More Election Meddling Than Russia, Has Done To Other Countries For Over A Century

By David Love - atlanta black star

March 18, 2018

With news of Russian meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election seizing the spotlight each day, America is now faced with the prospect of being victimized by the same practices it has promoted throughout the world. While Russia is receiving attention for its interference in the internal politics of the United States, Britain and other European nations, Uncle Sam has a long history of disrupting foreign governments, engaging in regime change, deposing elected leaders and even assassinating them.

Comparing the United States and Russia and their respective histories of overt and covert election influence in other countries, the former wins decisively. Carnegie Mellon University researcher Dov H. Levin has created a data set in which he found between 1946 and 2000, the U.S. interfered in foreign elections 81 times, while the Soviet Union and later Russia meddled on 36 occasions. “I’m not in any way justifying what the Russians did in 2016,” Levin told The New York Times. “It was completely wrong of Vladimir Putin to intervene in this way. That said, the methods they used in this election were the digital version of methods used both by the United States and Russia for decades: breaking into party headquarters, recruiting secretaries, placing informants in a party, giving information or disinformation to newspapers.”

Africa and the Caribbean provide ample evidence of a history of U.S. meddling in the elections of other nations. For example, Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was overthrown and assassinated in 1961 by the Belgians, who were reportedly aided and abetted by the CIA. The U.S. also had its own plan, which was not implemented, to assassinate Lumumba by lacing his toothpaste with poison, and otherwise remove him from power through other methods.

In 1966, the CIA was involved in the overthrow of Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah by way of a military coup. According to CIA intelligence officer John Stockwell in the book “In Search of Enemies,” the Accra office of the CIA had a “generous budget” and was encouraged by headquarters to maintain close contact with the coup plotters. According to a declassified U.S. government document, “The coup in Ghana is another example of a fortuitous windfall. Nkrumah was doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African. In reaction to his strongly pro-Communist leanings, the new military regime is almost pathetically pro-Western.” CIA participation in the coup was reportedly undertaken without approval from an interagency group that monitors clandestine CIA operations.

The U.S. Marines were on hand in 1912 to assist the Cuban government in destroying El Partido de Independiente de Color (PIC) or the Independent Party of Color, which was formed by descendants of slaves and became the first 20th century Black political party in the Western Hemisphere outside of Haiti. PIC — which believed in racial pride and equal rights for Black people — engaged in protest after the Cuban government banned the race-based party from participating in elections. In putting down the PIC, the United States invoked the Platt Amendment, which allowed American intervention in Cuban affairs. The military action from U.S. and Cuban forces resulted in the massacre of 6,000 Black people.

The U.S. occupied the Dominican Republic twice — from 1916 until 1924, controlling the government and who became president, and again in 1965, opposing elected president Juan Bosch, supporting a military coup and installing Joaquin Balaguer. President Reagan took advantage of the assassination of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop of Grenada and orchestrated its long planned invasion of the Caribbean nation, justifying the invasion on the grounds the regime was anti-American and supported by Cuba.

America is known for a high degree of intervention and coup sponsorship in Haiti, with military occupations and support for brutal dictators, and the ousting of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide under both Presidents George H.W. and George W. Bush. In 2009, during the Obama administration, Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was overthrown in a military coup and forced to fly to a U.S. military base at gunpoint and in his pajamas in an act of American-endorsed regime change. Although there was no evidence the Obama administration was involved in the coup, it did not stop it from taking place. The United States called for new elections rather than declaring a coup had taken place, and contributed to the subsequent deterioration and violence in Honduras. Elsewhere in Latin America, the U.S. was involved in the 1954 overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman, the democratically elected president of Guatemala, to protect the profits of the United Fruit Company.

In 1953, the CIA, with help from Great Britain, engineered a coup in Iran, overthrowing the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and installing a puppet regime under the Shah. This, after Mossadegh nationalized the British Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, later known as BP. In 1965, the U.S. Embassy supported the rise to power of Indonesia’s brutal dictator General Suharto, and enabled his massacre of over half a million Indonesians.. Ten years later, the U.S. helped Suharto with political and military support in his invasion of East Timor, which had declared independence from Portugal. The Indonesian occupation killed more than 200,000 Timorese, one third of the population.

With the 2016 presidential election, America now has experienced having another country meddle in its internal affairs — something which the U.S. has perpetrated against other nations for more than a century.

Comparing the United States and Russia and their respective histories of overt and covert election influence in other countries, the former wins decisively. Carnegie Mellon University researcher Dov H. Levin has created a data set in which he found between 1946 and 2000, the U.S. interfered in foreign elections 81 times, while the Soviet Union and later Russia meddled on 36 occasions. “I’m not in any way justifying what the Russians did in 2016,” Levin told The New York Times. “It was completely wrong of Vladimir Putin to intervene in this way. That said, the methods they used in this election were the digital version of methods used both by the United States and Russia for decades: breaking into party headquarters, recruiting secretaries, placing informants in a party, giving information or disinformation to newspapers.”

Africa and the Caribbean provide ample evidence of a history of U.S. meddling in the elections of other nations. For example, Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was overthrown and assassinated in 1961 by the Belgians, who were reportedly aided and abetted by the CIA. The U.S. also had its own plan, which was not implemented, to assassinate Lumumba by lacing his toothpaste with poison, and otherwise remove him from power through other methods.

In 1966, the CIA was involved in the overthrow of Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah by way of a military coup. According to CIA intelligence officer John Stockwell in the book “In Search of Enemies,” the Accra office of the CIA had a “generous budget” and was encouraged by headquarters to maintain close contact with the coup plotters. According to a declassified U.S. government document, “The coup in Ghana is another example of a fortuitous windfall. Nkrumah was doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African. In reaction to his strongly pro-Communist leanings, the new military regime is almost pathetically pro-Western.” CIA participation in the coup was reportedly undertaken without approval from an interagency group that monitors clandestine CIA operations.

The U.S. Marines were on hand in 1912 to assist the Cuban government in destroying El Partido de Independiente de Color (PIC) or the Independent Party of Color, which was formed by descendants of slaves and became the first 20th century Black political party in the Western Hemisphere outside of Haiti. PIC — which believed in racial pride and equal rights for Black people — engaged in protest after the Cuban government banned the race-based party from participating in elections. In putting down the PIC, the United States invoked the Platt Amendment, which allowed American intervention in Cuban affairs. The military action from U.S. and Cuban forces resulted in the massacre of 6,000 Black people.

The U.S. occupied the Dominican Republic twice — from 1916 until 1924, controlling the government and who became president, and again in 1965, opposing elected president Juan Bosch, supporting a military coup and installing Joaquin Balaguer. President Reagan took advantage of the assassination of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop of Grenada and orchestrated its long planned invasion of the Caribbean nation, justifying the invasion on the grounds the regime was anti-American and supported by Cuba.

America is known for a high degree of intervention and coup sponsorship in Haiti, with military occupations and support for brutal dictators, and the ousting of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide under both Presidents George H.W. and George W. Bush. In 2009, during the Obama administration, Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was overthrown in a military coup and forced to fly to a U.S. military base at gunpoint and in his pajamas in an act of American-endorsed regime change. Although there was no evidence the Obama administration was involved in the coup, it did not stop it from taking place. The United States called for new elections rather than declaring a coup had taken place, and contributed to the subsequent deterioration and violence in Honduras. Elsewhere in Latin America, the U.S. was involved in the 1954 overthrow of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman, the democratically elected president of Guatemala, to protect the profits of the United Fruit Company.

In 1953, the CIA, with help from Great Britain, engineered a coup in Iran, overthrowing the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and installing a puppet regime under the Shah. This, after Mossadegh nationalized the British Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, later known as BP. In 1965, the U.S. Embassy supported the rise to power of Indonesia’s brutal dictator General Suharto, and enabled his massacre of over half a million Indonesians.. Ten years later, the U.S. helped Suharto with political and military support in his invasion of East Timor, which had declared independence from Portugal. The Indonesian occupation killed more than 200,000 Timorese, one third of the population.

With the 2016 presidential election, America now has experienced having another country meddle in its internal affairs — something which the U.S. has perpetrated against other nations for more than a century.

Coard: America's 12 Slaveholding Presidents

Michael Coard - philly tribune

3/10/18

In my Freedom’s Journal columns on February 24 and March 3 here in The Philadelphia Tribune, I exposed the lies about President George Washington’s supposed wooden teeth and Thomas Jefferson’s supposed innocently romantic love affair with Sally Hemings.

Washington’s teeth were actually yanked from the mouths of our enslaved ancestors and Jefferson actually raped Sally repeatedly while she was just a child.

In response to both columns, white racists went certifiably crazy (I mean crazier) and denied and yelled and screamed and hollered and insulted. They also trolled on social media. Unfortunately for them, they’re gonna need a straight-jacket after reading this.

This week’s topic is about the twelve United States presidents who enslaved Black men, women, boys, and girls. And before you crazy racists start talking nonsense about those so-called “great” patriots simply being “men of their times,” you need to know that the anti-slavery movement amongst good white folks began in the 1730s and spread throughout the Thirteen Colonies as a result of the abolitionist activities during the First Great Awakening, which was early America’s Christian revival movement. Furthermore, the anti-slavery gospel of the Second Great Awakening was all over the nation from around 1790 through the 1850s.

America is and always has been a Christian country, right? Therefore, if the Christian revivalists weren’t men (and women) of that slaveholding time, why weren’t those twelve presidents who led this Christian country?

Beyond the religious abolitionist movement, the secular abolitionist movement was in full effect in the 1830s, thanks to the likes of the great newspaper publisher William Lloyd Garrison. Presidents knew how to read, right?

By the way, John Adams, the second president (from 1797-1801) and his son John Quincy Adams, the sixth president (from 1825-1829), never enslaved anybody. And they certainly were men of their times. Maybe they knew slavery was, is, and forever will be evil and inhumane.

Here are the evil and inhumane 12 slaveholding presidents listed from bad to worse to worst:

12. Martin Van Buren, the eighth president, enslaved 1 but not during his presidency. By the way, that 1 escaped.

11. Ulysses S. Grant, the eighteenth president, enslaved 5 but not during his presidency. In office from 1869-1877, he was the last slaveholding president.

10. Andrew Johnson, the seventeenth president, enslaved 8 but not during his presidency. However, when he was Military Governor of Tennessee, he persuaded President Abraham Lincoln to remove that state from those subject to “Honest Abe’s” Emancipation Proclamation.

9. William Henry Harrison, the ninth president, enslaved 11 but not during his presidency. However, as Governor of the Indiana Territory, he petitioned Congress to make slavery legal there. Fortunately, he was unsuccessful.

8. James K. Polk, the eleventh president, enslaved 25 and held many of them during his presidency. He also stole much of Mexico from the Mexicans during the 1846-1848 war in which those Brown people were robbed of California and almost all of today’s Southwest.

7. John Tyler, the tenth president, enslaved 70 and held many of them during his presidency. He was a states’ rights bigot and a jingoist flag-waver who robbed Mexico of Texas in 1845.

6. James Monroe, the fifth president, enslaved 75 and held many of them during his presidency. He hated Blacks so much that he wanted them sent back to Africa. That’s why he supported the racist American Colonization Society, robbed West Africans of a large piece of coastal land in 1821, and created a colony that later became Liberia. The Liberian state of Monrovia is named after that racist thug.

5. James Madison, the fourth president, enslaved approximately 100-125 and did so during his presidency. He’s the very same guy who proposed the Constitution’s Three-Fifths Clause.

4. Zachary Taylor, the twelfth president, enslaved approximately 150 and held many of them during his presidency. During his run for president in 1849, he campaigned on and bragged about his wholesale slaughter of Brown people when he was a Major General in the Mexican-American War. And white folks in America elected him.

3. Andrew Jackson, the seventh president, enslaved 150-200 and held many of them during his presidency. By the way, Jackson, nicknamed “Indian Killer”- whom fake President Donald Trump describes as his all-time favorite- wasn’t just a brutal slaveholder. He was also a genocidal monster who was responsible for the slaughter of approximately 30,000-50,000 Red men, women, and children. Moreover, he signed the horrific Indian Removal Act of 1830 that robbed the indigenous people of 25 million acres of fertile land and doomed them and their descendants to reservation ghettos.

2. Thomas Jefferson, the third president, enslaved 267 and held many of them during his presidency. For more info about this child rapist, read my March 3 column

1. George Washington, the first president, enslaved 316 and held many of them during his presidency. For more info about the man whose teeth were “yanked from the heads of his slaves,” read my February 24 column.

Washington’s teeth were actually yanked from the mouths of our enslaved ancestors and Jefferson actually raped Sally repeatedly while she was just a child.

In response to both columns, white racists went certifiably crazy (I mean crazier) and denied and yelled and screamed and hollered and insulted. They also trolled on social media. Unfortunately for them, they’re gonna need a straight-jacket after reading this.

This week’s topic is about the twelve United States presidents who enslaved Black men, women, boys, and girls. And before you crazy racists start talking nonsense about those so-called “great” patriots simply being “men of their times,” you need to know that the anti-slavery movement amongst good white folks began in the 1730s and spread throughout the Thirteen Colonies as a result of the abolitionist activities during the First Great Awakening, which was early America’s Christian revival movement. Furthermore, the anti-slavery gospel of the Second Great Awakening was all over the nation from around 1790 through the 1850s.

America is and always has been a Christian country, right? Therefore, if the Christian revivalists weren’t men (and women) of that slaveholding time, why weren’t those twelve presidents who led this Christian country?

Beyond the religious abolitionist movement, the secular abolitionist movement was in full effect in the 1830s, thanks to the likes of the great newspaper publisher William Lloyd Garrison. Presidents knew how to read, right?

By the way, John Adams, the second president (from 1797-1801) and his son John Quincy Adams, the sixth president (from 1825-1829), never enslaved anybody. And they certainly were men of their times. Maybe they knew slavery was, is, and forever will be evil and inhumane.

Here are the evil and inhumane 12 slaveholding presidents listed from bad to worse to worst:

12. Martin Van Buren, the eighth president, enslaved 1 but not during his presidency. By the way, that 1 escaped.

11. Ulysses S. Grant, the eighteenth president, enslaved 5 but not during his presidency. In office from 1869-1877, he was the last slaveholding president.

10. Andrew Johnson, the seventeenth president, enslaved 8 but not during his presidency. However, when he was Military Governor of Tennessee, he persuaded President Abraham Lincoln to remove that state from those subject to “Honest Abe’s” Emancipation Proclamation.

9. William Henry Harrison, the ninth president, enslaved 11 but not during his presidency. However, as Governor of the Indiana Territory, he petitioned Congress to make slavery legal there. Fortunately, he was unsuccessful.

8. James K. Polk, the eleventh president, enslaved 25 and held many of them during his presidency. He also stole much of Mexico from the Mexicans during the 1846-1848 war in which those Brown people were robbed of California and almost all of today’s Southwest.

7. John Tyler, the tenth president, enslaved 70 and held many of them during his presidency. He was a states’ rights bigot and a jingoist flag-waver who robbed Mexico of Texas in 1845.

6. James Monroe, the fifth president, enslaved 75 and held many of them during his presidency. He hated Blacks so much that he wanted them sent back to Africa. That’s why he supported the racist American Colonization Society, robbed West Africans of a large piece of coastal land in 1821, and created a colony that later became Liberia. The Liberian state of Monrovia is named after that racist thug.

5. James Madison, the fourth president, enslaved approximately 100-125 and did so during his presidency. He’s the very same guy who proposed the Constitution’s Three-Fifths Clause.

4. Zachary Taylor, the twelfth president, enslaved approximately 150 and held many of them during his presidency. During his run for president in 1849, he campaigned on and bragged about his wholesale slaughter of Brown people when he was a Major General in the Mexican-American War. And white folks in America elected him.

3. Andrew Jackson, the seventh president, enslaved 150-200 and held many of them during his presidency. By the way, Jackson, nicknamed “Indian Killer”- whom fake President Donald Trump describes as his all-time favorite- wasn’t just a brutal slaveholder. He was also a genocidal monster who was responsible for the slaughter of approximately 30,000-50,000 Red men, women, and children. Moreover, he signed the horrific Indian Removal Act of 1830 that robbed the indigenous people of 25 million acres of fertile land and doomed them and their descendants to reservation ghettos.

2. Thomas Jefferson, the third president, enslaved 267 and held many of them during his presidency. For more info about this child rapist, read my March 3 column

1. George Washington, the first president, enslaved 316 and held many of them during his presidency. For more info about the man whose teeth were “yanked from the heads of his slaves,” read my February 24 column.

A historian explains why Robert E. Lee wasn’t a hero — he was a traitor

November 20, 2019

By History News Network- Commentary - raw story

There’s a fabled moment from the Battle of Fredericksburg, a gruesome Civil War battle that extinguished several thousand lives, when the commander of a rebel army looked down upon the carnage and said, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.” That commander, of course, was Robert Lee.

The moment is the stuff of legend. It captures Lee’s humility (he won the battle), compassion, and thoughtfulness. It casts Lee as a reluctant leader who had no choice but to serve his people, and who might have had second thoughts about doing so given the conflict’s tremendous amount of violence and bloodshed. The quote, however, is misleading. Lee was no hero. He was neither noble nor wise. Lee was a traitor who killed United States soldiers, fought for human enslavement, vastly increased the bloodshed of the Civil War, and made embarrassing tactical mistakes.

1) Lee was a traitor

Robert Lee was the nation’s most notable traitor since Benedict Arnold. Like Arnold, Robert Lee had an exceptional record of military service before his downfall. Lee was a hero of the Mexican-American War and played a crucial role in its final, decisive campaign to take Mexico City. But when he was called on to serve again—this time against violent rebels who were occupying and attacking federal forts—Lee failed to honor his oath to defend the Constitution. He resigned from the United States Army and quickly accepted a commission in a rebel army based in Virginia. Lee could have chosen to abstain from the conflict—it was reasonable to have qualms about leading United States soldiers against American citizens—but he did not abstain. He turned against his nation and took up arms against it. How could Lee, a lifelong soldier of the United States, so quickly betray it?

2) Lee fought for slavery

Robert Lee understood as well as any other contemporary the issue that ignited the secession crisis. Wealthy white plantation owners in the South had spent the better part of a century slowly taking over the United States government. With each new political victory, they expanded human enslavement further and further until the oligarchs of the Cotton South were the wealthiest single group of people on the planet. It was a kind of power and wealth they were willing to kill and die to protect.

According to Northwest Ordinance of 1787, new lands and territories in the West were supposed to be free while largescale human enslavement remained in the South. In 1820, however, Southerners amended that rule by dividing new lands between a free North and slave South. In the 1830s, Southerners used their inflated representation in Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act, an obvious and ultimately successful effort to take fertile Indian land and transform it into productive slave plantations. The Compromise of 1850 forced Northern states to enforce fugitive slave laws, a blatant assault on the rights of Northern states to legislate against human enslavement. In 1854, Southerners moved the goal posts again and decided that residents in new states and territories could decide the slave question for themselves. Violent clashes between pro- and anti-slavery forces soon followed in Kansas.

The South’s plans to expand slavery reached a crescendo in 1857 with the Dred Scott Decision. In the decision, the Supreme Court ruled that since the Constitution protected property and enslaved humans were considered property, territories could not make laws against slavery.

The details are less important than the overall trend: in the seventy years after the Constitution was written, a small group of Southerner oligarchs took over the government and transformed the United States into a pro-slavery nation. As one young politician put it, “We shall lie pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State.”

The ensuing fury over the expansion of slave power in the federal government prompted a historic backlash. Previously divided Americans rallied behind a new political party and the young, brilliant politician quoted above. Abraham Lincoln presented a clear message: should he be elected, the federal government would no longer legislate in favor of enslavement, and would work to stop its expansion into the West.

Lincoln’s election in 1860 was not simply a single political loss for slaveholding Southerners. It represented a collapse of their minority political dominance of the federal government, without which they could not maintain and expand slavery to full extent of their desires. Foiled by democracy, Southern oligarchs disavowed it and declared independence from the United States.

Their rebel organization—the “Confederate States of America,” a cheap imitation of the United States government stripped of its language of equality, freedom, and justice—did not care much for states’ rights. States in the Confederacy forfeited both the right to secede from it and the right to limit or eliminate slavery. What really motivated the new CSA was not only obvious, but repeatedly declared. In their articles of secession, which explained their motivations for violent insurrection, rebel leaders in the South cited slavery. Georgia cited slavery. Mississippi cited slavery. South Carolina cited the “increasing hostility… to the institution of slavery.” Texas cited slavery. Virginia cited the “oppression of… Southern slaveholding.” Alexander Stephens, the second in command of the rebel cabal, declared in his Cornerstone Speech that they had launched the entire enterprise because the Founding Fathers had made a mistake in declaring that all people are made equal. “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea,” he said. People of African descent were supposed to be enslaved.

Despite making a few cryptic comments about how he refused to fight his fellow Virginians, Lee would have understood exactly what the war was about and how it served wealthy white men like him. Lee was a slave-holding aristocrat with ties to George Washington. He was the face of Southern gentry, a kind of pseudo royalty in a land that had theoretically extinguished it. The triumph of the South would have meant the triumph not only of Lee, but everything he represented: that tiny, self-defined perfect portion at the top of a violently unequal pyramid.

Yet even if Lee disavowed slavery and fought only for some vague notion of states’ rights, would that have made a difference? War is a political tool that serves a political purpose. If the purpose of the rebellion was to create a powerful, endless slave empire (it was), then do the opinions of its soldiers and commanders really matter? Each victory of Lee’s, each rebel bullet that felled a United States soldier, advanced the political cause of the CSA. Had Lee somehow defeated the United States Army, marched to the capital, killed the President, and won independence for the South, the result would have been the preservation of slavery in North America. There would have been no Thirteenth Amendment. Lincoln would not have overseen the emancipation of four million people, the largest single emancipation event in human history. Lee’s successes were the successes of the Slave South, personal feelings be damned.

If you need more evidence of Lee’s personal feelings on enslavement, however, note that when his rebel forces marched into Pennsylvania, they kidnapped black people and sold them into bondage. Contemporaries referred to these kidnappings as “slave hunts.”

3) Lee was not a military genius

Despite a mythology around Lee being the Napoleon of America, Lee blundered his way to a surrender. To be fair to Lee, his early victories were impressive. Lee earned command of the largest rebel army in 1862 and quickly put his experience to work. His interventions at the end of the Peninsula Campaign and his aggressive flanking movements at the Battle of Second Manassas ensured that the United States Army could not achieve a quick victory over rebel forces. At Fredericksburg, Lee also demonstrated a keen understanding of how to establish a strong defensive position, and foiled another US offensive. Lee’s shining moment came later at Chancellorsville, when he again maneuvered his smaller but more mobile force to flank and rout the US Army. Yet Lee’s broader strategy was deeply flawed, and ended with his most infamous blunder.

Lee should have recognized that the objective of his army was not to defeat the larger United States forces that he faced. Rather, he needed to simply prevent those armies from taking Richmond, the city that housed the rebel government, until the United States government lost support for the war and sued for peace. New military technology that greatly favored defenders would have bolstered this strategy. But Lee opted for a different strategy, taking his army and striking northward into areas that the United States government still controlled.

It’s tempting to think that Lee’s strategy was sound and could have delivered a decisive blow, but it’s far more likely that he was starting to believe that his men truly were superior and that his army was essentially unstoppable, as many supporters in the South were openly speculating. Even the Battle of Antietam, an aggressive invasion that ended in a terrible rebel loss, did not dissuade Lee from this thinking. After Chancellorsville, Lee marched his army into Pennsylvania where he ran into the United States Army at the town of Gettysburg. After a few days of fighting into a stalemate, Lee decided against withdrawing as he had done at Antietam. Instead, he doubled down on his aggressive strategy and ordered a direct assault over open terrain straight into the heart of the US Army’s lines.

The result—several thousand casualties—was devastating. It was a crushing blow and a terrible military decision from which Lee and his men never fully recovered. The loss also bolstered support for the war effort and Lincoln in the North, almost guaranteeing that the United States would not stop short of a total victory.

4) Lee, not Grant, was responsible for the staggering losses of the Civil War

The Civil War dragged on even after Lee’s horrific loss at Gettysburg. Even after it was clear that the rebels were in trouble, with white women in the South rioting for bread, conscripted men deserting, and thousands of enslaved people self-emancipating, Lee and his men dug in and continued to fight. Only after going back on the defensive—that is, digging in on hills and building massive networks of trenches and fortifications—did Lee start to achieve lopsided results again. Civil War enthusiasts often point to the resulting carnage as evidence that Ulysses S. Grant, the new General of the entire United States Army, did not care about the terrible losses and should be criticized for how he threw wave after wave of men at entrenched rebel positions. In reality, however, the situation was completely of Lee’s making.

As Grant doggedly pursued Lee’s forces, he did his best to flush Lee into an open field for a decisive battle, like at Antietam or Gettysburg. Lee refused to accept, however, knowing that a crushing loss likely awaited him. Lee also could have abandoned the area around the rebel capital and allowed the United States to achieve a moral and political victory. Both of these options would have drastically reduced the loss of life on both sides and ended the war earlier. Lee chose neither option. Rather, he maneuvered his forces in such a way that they always had a secure, defensive position, daring Grant to sacrifice more men. When Grant did this and overran the rebel positions, Lee pulled back and repeated the process. The result was the most gruesome period of the war. It was not uncommon for dead bodies to be stacked upon each other after waves of attacks and counterattacks clashed at the same position. At the Wilderness, the forest caught fire, trapping wounded men from both sides in the inferno. Their comrades listened helplessly to the screams as the men in the forest burned alive.

To his credit, when the war was truly lost—the rebel capital sacked (burned by retreating rebel soldiers), the infrastructure of the South in ruins, and Lee’s army chased one hundred miles into the west—Lee chose not to engage in guerrilla warfare and surrendered, though the decision was likely based on image more than a concern for human life. He showed up to Grant’s camp, after all, dressed in a new uniform and riding a white horse. So ended the military career of Robert Lee, a man responsible for the death of more United States soldiers than any single commander in history.

So why, after all of this, do some Americans still celebrate Lee? Well, many white Southerners refused to accept the outcome of the Civil War. After years of terrorism, local political coups, wholesale massacres, and lynchings, white Southerners were able to retake power in the South. While they erected monuments to war criminals like Nathan Bedford Forrest to send a clear message to would-be civil rights activists, white southerners also needed someone who represented the “greatness” of the Old South, someone of whom they could be proud. They turned to Robert Lee.

But Lee was not great. In fact, he represented the very worst of the Old South, a man willing to betray his republic and slaughter his countrymen to preserve a violent, unfree society that elevated him and just a handful of others like him. He was the gentle face of a brutal system. And for all his acclaim, Lee was not a military genius. He was a flawed aristocrat who fell in love with the mythology of his own invincibility.

After the war, Robert Lee lived out the remainder of his days. He was neither arrested nor hanged. But it is up to us how we remember him. Memory is often the trial that evil men never received. Perhaps we should take a page from the United States Army of the Civil War, which needed to decide what to do with the slave plantation it seized from the Lee family. Ultimately, the Army decided to use Lee’s land as a cemetery, transforming the land from a site of human enslavement to a final resting place for United States soldiers who died to make men free. You can visit that cemetery today. After all, who hasn’t heard of Arlington Cemetery?

The moment is the stuff of legend. It captures Lee’s humility (he won the battle), compassion, and thoughtfulness. It casts Lee as a reluctant leader who had no choice but to serve his people, and who might have had second thoughts about doing so given the conflict’s tremendous amount of violence and bloodshed. The quote, however, is misleading. Lee was no hero. He was neither noble nor wise. Lee was a traitor who killed United States soldiers, fought for human enslavement, vastly increased the bloodshed of the Civil War, and made embarrassing tactical mistakes.

1) Lee was a traitor

Robert Lee was the nation’s most notable traitor since Benedict Arnold. Like Arnold, Robert Lee had an exceptional record of military service before his downfall. Lee was a hero of the Mexican-American War and played a crucial role in its final, decisive campaign to take Mexico City. But when he was called on to serve again—this time against violent rebels who were occupying and attacking federal forts—Lee failed to honor his oath to defend the Constitution. He resigned from the United States Army and quickly accepted a commission in a rebel army based in Virginia. Lee could have chosen to abstain from the conflict—it was reasonable to have qualms about leading United States soldiers against American citizens—but he did not abstain. He turned against his nation and took up arms against it. How could Lee, a lifelong soldier of the United States, so quickly betray it?

2) Lee fought for slavery

Robert Lee understood as well as any other contemporary the issue that ignited the secession crisis. Wealthy white plantation owners in the South had spent the better part of a century slowly taking over the United States government. With each new political victory, they expanded human enslavement further and further until the oligarchs of the Cotton South were the wealthiest single group of people on the planet. It was a kind of power and wealth they were willing to kill and die to protect.

According to Northwest Ordinance of 1787, new lands and territories in the West were supposed to be free while largescale human enslavement remained in the South. In 1820, however, Southerners amended that rule by dividing new lands between a free North and slave South. In the 1830s, Southerners used their inflated representation in Congress to pass the Indian Removal Act, an obvious and ultimately successful effort to take fertile Indian land and transform it into productive slave plantations. The Compromise of 1850 forced Northern states to enforce fugitive slave laws, a blatant assault on the rights of Northern states to legislate against human enslavement. In 1854, Southerners moved the goal posts again and decided that residents in new states and territories could decide the slave question for themselves. Violent clashes between pro- and anti-slavery forces soon followed in Kansas.

The South’s plans to expand slavery reached a crescendo in 1857 with the Dred Scott Decision. In the decision, the Supreme Court ruled that since the Constitution protected property and enslaved humans were considered property, territories could not make laws against slavery.

The details are less important than the overall trend: in the seventy years after the Constitution was written, a small group of Southerner oligarchs took over the government and transformed the United States into a pro-slavery nation. As one young politician put it, “We shall lie pleasantly dreaming that the people of Missouri are on the verge of making their State free; and we shall awake to the reality, instead, that the Supreme Court has made Illinois a slave State.”

The ensuing fury over the expansion of slave power in the federal government prompted a historic backlash. Previously divided Americans rallied behind a new political party and the young, brilliant politician quoted above. Abraham Lincoln presented a clear message: should he be elected, the federal government would no longer legislate in favor of enslavement, and would work to stop its expansion into the West.

Lincoln’s election in 1860 was not simply a single political loss for slaveholding Southerners. It represented a collapse of their minority political dominance of the federal government, without which they could not maintain and expand slavery to full extent of their desires. Foiled by democracy, Southern oligarchs disavowed it and declared independence from the United States.

Their rebel organization—the “Confederate States of America,” a cheap imitation of the United States government stripped of its language of equality, freedom, and justice—did not care much for states’ rights. States in the Confederacy forfeited both the right to secede from it and the right to limit or eliminate slavery. What really motivated the new CSA was not only obvious, but repeatedly declared. In their articles of secession, which explained their motivations for violent insurrection, rebel leaders in the South cited slavery. Georgia cited slavery. Mississippi cited slavery. South Carolina cited the “increasing hostility… to the institution of slavery.” Texas cited slavery. Virginia cited the “oppression of… Southern slaveholding.” Alexander Stephens, the second in command of the rebel cabal, declared in his Cornerstone Speech that they had launched the entire enterprise because the Founding Fathers had made a mistake in declaring that all people are made equal. “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea,” he said. People of African descent were supposed to be enslaved.

Despite making a few cryptic comments about how he refused to fight his fellow Virginians, Lee would have understood exactly what the war was about and how it served wealthy white men like him. Lee was a slave-holding aristocrat with ties to George Washington. He was the face of Southern gentry, a kind of pseudo royalty in a land that had theoretically extinguished it. The triumph of the South would have meant the triumph not only of Lee, but everything he represented: that tiny, self-defined perfect portion at the top of a violently unequal pyramid.

Yet even if Lee disavowed slavery and fought only for some vague notion of states’ rights, would that have made a difference? War is a political tool that serves a political purpose. If the purpose of the rebellion was to create a powerful, endless slave empire (it was), then do the opinions of its soldiers and commanders really matter? Each victory of Lee’s, each rebel bullet that felled a United States soldier, advanced the political cause of the CSA. Had Lee somehow defeated the United States Army, marched to the capital, killed the President, and won independence for the South, the result would have been the preservation of slavery in North America. There would have been no Thirteenth Amendment. Lincoln would not have overseen the emancipation of four million people, the largest single emancipation event in human history. Lee’s successes were the successes of the Slave South, personal feelings be damned.

If you need more evidence of Lee’s personal feelings on enslavement, however, note that when his rebel forces marched into Pennsylvania, they kidnapped black people and sold them into bondage. Contemporaries referred to these kidnappings as “slave hunts.”

3) Lee was not a military genius

Despite a mythology around Lee being the Napoleon of America, Lee blundered his way to a surrender. To be fair to Lee, his early victories were impressive. Lee earned command of the largest rebel army in 1862 and quickly put his experience to work. His interventions at the end of the Peninsula Campaign and his aggressive flanking movements at the Battle of Second Manassas ensured that the United States Army could not achieve a quick victory over rebel forces. At Fredericksburg, Lee also demonstrated a keen understanding of how to establish a strong defensive position, and foiled another US offensive. Lee’s shining moment came later at Chancellorsville, when he again maneuvered his smaller but more mobile force to flank and rout the US Army. Yet Lee’s broader strategy was deeply flawed, and ended with his most infamous blunder.

Lee should have recognized that the objective of his army was not to defeat the larger United States forces that he faced. Rather, he needed to simply prevent those armies from taking Richmond, the city that housed the rebel government, until the United States government lost support for the war and sued for peace. New military technology that greatly favored defenders would have bolstered this strategy. But Lee opted for a different strategy, taking his army and striking northward into areas that the United States government still controlled.

It’s tempting to think that Lee’s strategy was sound and could have delivered a decisive blow, but it’s far more likely that he was starting to believe that his men truly were superior and that his army was essentially unstoppable, as many supporters in the South were openly speculating. Even the Battle of Antietam, an aggressive invasion that ended in a terrible rebel loss, did not dissuade Lee from this thinking. After Chancellorsville, Lee marched his army into Pennsylvania where he ran into the United States Army at the town of Gettysburg. After a few days of fighting into a stalemate, Lee decided against withdrawing as he had done at Antietam. Instead, he doubled down on his aggressive strategy and ordered a direct assault over open terrain straight into the heart of the US Army’s lines.

The result—several thousand casualties—was devastating. It was a crushing blow and a terrible military decision from which Lee and his men never fully recovered. The loss also bolstered support for the war effort and Lincoln in the North, almost guaranteeing that the United States would not stop short of a total victory.

4) Lee, not Grant, was responsible for the staggering losses of the Civil War

The Civil War dragged on even after Lee’s horrific loss at Gettysburg. Even after it was clear that the rebels were in trouble, with white women in the South rioting for bread, conscripted men deserting, and thousands of enslaved people self-emancipating, Lee and his men dug in and continued to fight. Only after going back on the defensive—that is, digging in on hills and building massive networks of trenches and fortifications—did Lee start to achieve lopsided results again. Civil War enthusiasts often point to the resulting carnage as evidence that Ulysses S. Grant, the new General of the entire United States Army, did not care about the terrible losses and should be criticized for how he threw wave after wave of men at entrenched rebel positions. In reality, however, the situation was completely of Lee’s making.

As Grant doggedly pursued Lee’s forces, he did his best to flush Lee into an open field for a decisive battle, like at Antietam or Gettysburg. Lee refused to accept, however, knowing that a crushing loss likely awaited him. Lee also could have abandoned the area around the rebel capital and allowed the United States to achieve a moral and political victory. Both of these options would have drastically reduced the loss of life on both sides and ended the war earlier. Lee chose neither option. Rather, he maneuvered his forces in such a way that they always had a secure, defensive position, daring Grant to sacrifice more men. When Grant did this and overran the rebel positions, Lee pulled back and repeated the process. The result was the most gruesome period of the war. It was not uncommon for dead bodies to be stacked upon each other after waves of attacks and counterattacks clashed at the same position. At the Wilderness, the forest caught fire, trapping wounded men from both sides in the inferno. Their comrades listened helplessly to the screams as the men in the forest burned alive.

To his credit, when the war was truly lost—the rebel capital sacked (burned by retreating rebel soldiers), the infrastructure of the South in ruins, and Lee’s army chased one hundred miles into the west—Lee chose not to engage in guerrilla warfare and surrendered, though the decision was likely based on image more than a concern for human life. He showed up to Grant’s camp, after all, dressed in a new uniform and riding a white horse. So ended the military career of Robert Lee, a man responsible for the death of more United States soldiers than any single commander in history.

So why, after all of this, do some Americans still celebrate Lee? Well, many white Southerners refused to accept the outcome of the Civil War. After years of terrorism, local political coups, wholesale massacres, and lynchings, white Southerners were able to retake power in the South. While they erected monuments to war criminals like Nathan Bedford Forrest to send a clear message to would-be civil rights activists, white southerners also needed someone who represented the “greatness” of the Old South, someone of whom they could be proud. They turned to Robert Lee.

But Lee was not great. In fact, he represented the very worst of the Old South, a man willing to betray his republic and slaughter his countrymen to preserve a violent, unfree society that elevated him and just a handful of others like him. He was the gentle face of a brutal system. And for all his acclaim, Lee was not a military genius. He was a flawed aristocrat who fell in love with the mythology of his own invincibility.

After the war, Robert Lee lived out the remainder of his days. He was neither arrested nor hanged. But it is up to us how we remember him. Memory is often the trial that evil men never received. Perhaps we should take a page from the United States Army of the Civil War, which needed to decide what to do with the slave plantation it seized from the Lee family. Ultimately, the Army decided to use Lee’s land as a cemetery, transforming the land from a site of human enslavement to a final resting place for United States soldiers who died to make men free. You can visit that cemetery today. After all, who hasn’t heard of Arlington Cemetery?

Andrew Johnson’s failed presidency echoes in Trump’s White House

The Conversation - raw story

19 FEB 2018 AT 07:43 ET

The two have much in common. Like Trump, Johnson followed an unconventional path to the presidency.

A Tennessean and lifelong Democrat, Johnson was a defender of slavery and white supremacy but also an uncompromising Unionist. He was the only U.S. senator from the South who opposed his state’s move to secede in 1861. That made him an unconventional yet attractive choice as Abraham Lincoln’s running mate in 1864 when Republicans took on the mantle of the “Union Party” to win support from Democrats alienated by their own party’s anti-war stance.

Six weeks after becoming vice president, an assassin’s bullet killed Lincoln and catapulted Johnson to the presidency.

Republican reception mixed for JohnsonLike Trump, Johnson entered the White House with a mixture of skepticism and support among Republicans who controlled Congress. He was a Southerner and a Democrat, which concerned them. But his courageous Unionism and blunt criticism of rebels – “Treason must be made infamous and traitors punished,” he proclaimed – impressed congressional leaders, who believed that he would take a firm approach to the South.

Through bold assertion of executive authority, Johnson quickly reconstructed state and local governments in the South. Because African-Americans were excluded from the process, these regimes were controlled by Southern whites, most of whom had been loyal Confederates. Predictably, they adopted laws designed to keep African-Americans in a servile position.

Southern officials also stood by and even abetted whites who unleashed a wave of violence against former slaves. For example, in July 1866, New Orleans police participated in a massacre that left 37 African-Americans and white Unionists dead and more than 100 wounded.

Unlike today’s Republicans, most of whom have become more loyal to Trump, Reconstruction-era Republicans pushed back against Johnson. They viewed emancipation as a crowning achievement of Union victory and were determined to ensure that former slaves enjoyed the fruits of freedom. Although they hoped to avoid conflict with the president, in early 1866, they adopted measures designed to establish color-blind citizenship and protect former slaves from injustice.

No fan of negotiationLike Trump, Johnson’s instinct was to attack rather than negotiate. A states’ rights Democrat and proponent of white supremacy, Johnson rebuffed Republicans’ efforts at compromise. He responded to Republican civil rights legislation with scathing veto messages. In September 1866, he toured the North, leveling personal attacks against congressional leaders and seeking to rally voters against them in the midterm elections.

Growing up poor and illiterate, Johnson had developed a deep hostility for African-Americans, believing that they looked down on people like him. His private conversations were laced with racist invective. After meeting with a delegation led by the black leader, Frederick Douglass, for example, he exclaimed to his secretary, “I know that damned Douglass; he’s just like any n—-r, and he would just as likely cut a white man’s throat as not.”

In speeches on the campaign trail and in Washington, Johnson cast his opposition to Republican civil rights policy in language that today appears clearly racist. He sought to appeal to voters — North as well as South – who felt threatened by African-American gains.

In vetoing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Johnson argued that African-Americans, who had “just emerged from slavery,” lacked “the requisite qualifications to entitle them to the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.” Indeed, he asserted, the law discriminated “against large numbers of intelligent, worthy, and patriotic foreigners [who had to reside in the U.S. for five years to qualify for citizenship] in favor of the negro.”

Made excuses for Southern racismJohnson excused racist violence in the South. Ignoring facts that had been widely reported in the press, Johnson held Republicans in Congress responsible for encouraging black political activism during the New Orleans massacre. That was the July 1866 riot where a white mob – aided by police – set upon African-American marchers and their white Unionist sympathizers, leaving 37 African-Americans and white Unionists dead and more than 100 wounded.

“Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts,” Johnson charged, “and they are responsible for it.” Whites who encouraged blacks to demand the right to vote, not the white mobs and police who attacked them, bore responsibility, Johnson implied.

Like Trump, Johnson fancied himself a populist. He saw himself as a principled defender of the people against Washington insiders bent on destroying the republic. By refusing to seat senators and representatives from the reconstructed states of the former Confederacy, he charged in 1866, congressional leaders were riding roughshod over the Constitution.

“There are individuals in the Government,” Johnson told an audience in Washington, D.C., “who want to destroy our institutions.”

Later, when confronted by catcalls from Republican partisans, Johnson fired back.

“Congress is trying to break up the Government,” he said, casting congressional leaders as enemies of the Union in the mold of secessionist heroes Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee.

Combining egotism, victimhood and paranoia in a manner similar to Trump, Johnson portrayed himself as the nation’s much maligned savior.

“I am your instrument,” he told one audience. “I stand for the country, I stand for the Constitution.”

The public could get tickets to attend the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson.

Johnson saw his opponents as enemies bent not just on impugning the legitimacy of his presidency but whose “intention … [is] to incite assassination.” In a melodramatic and revealing pledge, he proclaimed, “If my blood is to be shed because I vindicate the Union … then let it be shed.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Johnson’s presidency ended badly.

Reviled by African-AmericansWhile lauded by white Southerners, he was reviled by African-Americans and most Northerners for disgracing the office of the presidency. Thomas Nast, the popular political cartoonist, lampooned him, the press chastised him and private citizens expressed their disgust.

Commenting on Johnson’s electioneering tour of the North, Mary Todd Lincoln said acidly that his conduct “would humiliate any other than himself.”

Congressional Republicans overrode Johnson’s vetoes and tied his hands on matters of policy. In 1868, the House of Representatives voted to impeach him but the Senate fell one vote shy of the two-thirds majority necessary to remove him from office.

As his term came to an end in 1869, his successor, Ulysses Grant, refused to ride to the inauguration in the same carriage as the disgraced Johnson, who then declined to attend the ceremony. Instead, he remained at the White House, leaving it for the last time to go to his Tennessee home — and perhaps a more receptive audience of like-minded Southerners — after the inauguration was over.

Presidents succeed by appealing to shared values, uniting rather than dividing, making strategic use of the respect Americans have for the office, and avoiding the gutter. Andrew Johnson failed on all counts, destroying his presidency and bringing himself into contempt.

The Washington Post’s Senior Editor Marc Fisher writes that Donald Trump learned as a real estate developer and entertainer “that what humiliates, damages, even destroys others can actually strengthen his image and therefore his bottom line.”

Will those lessons serve Trump well as president? Or will they condemn him to Johnson’s ignominious fate?

Donald Nieman, Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost, Binghamton University, State University of New York

A Tennessean and lifelong Democrat, Johnson was a defender of slavery and white supremacy but also an uncompromising Unionist. He was the only U.S. senator from the South who opposed his state’s move to secede in 1861. That made him an unconventional yet attractive choice as Abraham Lincoln’s running mate in 1864 when Republicans took on the mantle of the “Union Party” to win support from Democrats alienated by their own party’s anti-war stance.

Six weeks after becoming vice president, an assassin’s bullet killed Lincoln and catapulted Johnson to the presidency.

Republican reception mixed for JohnsonLike Trump, Johnson entered the White House with a mixture of skepticism and support among Republicans who controlled Congress. He was a Southerner and a Democrat, which concerned them. But his courageous Unionism and blunt criticism of rebels – “Treason must be made infamous and traitors punished,” he proclaimed – impressed congressional leaders, who believed that he would take a firm approach to the South.

Through bold assertion of executive authority, Johnson quickly reconstructed state and local governments in the South. Because African-Americans were excluded from the process, these regimes were controlled by Southern whites, most of whom had been loyal Confederates. Predictably, they adopted laws designed to keep African-Americans in a servile position.

Southern officials also stood by and even abetted whites who unleashed a wave of violence against former slaves. For example, in July 1866, New Orleans police participated in a massacre that left 37 African-Americans and white Unionists dead and more than 100 wounded.

Unlike today’s Republicans, most of whom have become more loyal to Trump, Reconstruction-era Republicans pushed back against Johnson. They viewed emancipation as a crowning achievement of Union victory and were determined to ensure that former slaves enjoyed the fruits of freedom. Although they hoped to avoid conflict with the president, in early 1866, they adopted measures designed to establish color-blind citizenship and protect former slaves from injustice.

No fan of negotiationLike Trump, Johnson’s instinct was to attack rather than negotiate. A states’ rights Democrat and proponent of white supremacy, Johnson rebuffed Republicans’ efforts at compromise. He responded to Republican civil rights legislation with scathing veto messages. In September 1866, he toured the North, leveling personal attacks against congressional leaders and seeking to rally voters against them in the midterm elections.

Growing up poor and illiterate, Johnson had developed a deep hostility for African-Americans, believing that they looked down on people like him. His private conversations were laced with racist invective. After meeting with a delegation led by the black leader, Frederick Douglass, for example, he exclaimed to his secretary, “I know that damned Douglass; he’s just like any n—-r, and he would just as likely cut a white man’s throat as not.”

In speeches on the campaign trail and in Washington, Johnson cast his opposition to Republican civil rights policy in language that today appears clearly racist. He sought to appeal to voters — North as well as South – who felt threatened by African-American gains.

In vetoing the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Johnson argued that African-Americans, who had “just emerged from slavery,” lacked “the requisite qualifications to entitle them to the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States.” Indeed, he asserted, the law discriminated “against large numbers of intelligent, worthy, and patriotic foreigners [who had to reside in the U.S. for five years to qualify for citizenship] in favor of the negro.”

Made excuses for Southern racismJohnson excused racist violence in the South. Ignoring facts that had been widely reported in the press, Johnson held Republicans in Congress responsible for encouraging black political activism during the New Orleans massacre. That was the July 1866 riot where a white mob – aided by police – set upon African-American marchers and their white Unionist sympathizers, leaving 37 African-Americans and white Unionists dead and more than 100 wounded.

“Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts,” Johnson charged, “and they are responsible for it.” Whites who encouraged blacks to demand the right to vote, not the white mobs and police who attacked them, bore responsibility, Johnson implied.

Like Trump, Johnson fancied himself a populist. He saw himself as a principled defender of the people against Washington insiders bent on destroying the republic. By refusing to seat senators and representatives from the reconstructed states of the former Confederacy, he charged in 1866, congressional leaders were riding roughshod over the Constitution.

“There are individuals in the Government,” Johnson told an audience in Washington, D.C., “who want to destroy our institutions.”

Later, when confronted by catcalls from Republican partisans, Johnson fired back.

“Congress is trying to break up the Government,” he said, casting congressional leaders as enemies of the Union in the mold of secessionist heroes Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee.

Combining egotism, victimhood and paranoia in a manner similar to Trump, Johnson portrayed himself as the nation’s much maligned savior.

“I am your instrument,” he told one audience. “I stand for the country, I stand for the Constitution.”

The public could get tickets to attend the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson.

Johnson saw his opponents as enemies bent not just on impugning the legitimacy of his presidency but whose “intention … [is] to incite assassination.” In a melodramatic and revealing pledge, he proclaimed, “If my blood is to be shed because I vindicate the Union … then let it be shed.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Johnson’s presidency ended badly.

Reviled by African-AmericansWhile lauded by white Southerners, he was reviled by African-Americans and most Northerners for disgracing the office of the presidency. Thomas Nast, the popular political cartoonist, lampooned him, the press chastised him and private citizens expressed their disgust.

Commenting on Johnson’s electioneering tour of the North, Mary Todd Lincoln said acidly that his conduct “would humiliate any other than himself.”

Congressional Republicans overrode Johnson’s vetoes and tied his hands on matters of policy. In 1868, the House of Representatives voted to impeach him but the Senate fell one vote shy of the two-thirds majority necessary to remove him from office.

As his term came to an end in 1869, his successor, Ulysses Grant, refused to ride to the inauguration in the same carriage as the disgraced Johnson, who then declined to attend the ceremony. Instead, he remained at the White House, leaving it for the last time to go to his Tennessee home — and perhaps a more receptive audience of like-minded Southerners — after the inauguration was over.

Presidents succeed by appealing to shared values, uniting rather than dividing, making strategic use of the respect Americans have for the office, and avoiding the gutter. Andrew Johnson failed on all counts, destroying his presidency and bringing himself into contempt.

The Washington Post’s Senior Editor Marc Fisher writes that Donald Trump learned as a real estate developer and entertainer “that what humiliates, damages, even destroys others can actually strengthen his image and therefore his bottom line.”

Will those lessons serve Trump well as president? Or will they condemn him to Johnson’s ignominious fate?

Donald Nieman, Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost, Binghamton University, State University of New York

they knew!!!

On its hundredth birthday in 1959, Edward Teller warned the oil industry about global warming

Somebody cut the cake – new documents reveal that American oil writ large was warned of global warming at its 100th birthday party.

Benjamin Franta

the guardian

Mon 1 Jan ‘18 06.00 EST

...The nuclear weapons physicist Edward Teller had, by 1959, become ostracized by the scientific community for betraying his colleague J. Robert Oppenheimer, but he retained the embrace of industry and government. Teller’s task that November fourth was to address the crowd on “energy patterns of the future,” and his words carried an unexpected warning:

Ladies and gentlemen, I am to talk to you about energy in the future. I will start by telling you why I believe that the energy resources of the past must be supplemented. First of all, these energy resources will run short as we use more and more of the fossil fuels. But I would [...] like to mention another reason why we probably have to look for additional fuel supplies. And this, strangely, is the question of contaminating the atmosphere. [....] Whenever you burn conventional fuel, you create carbon dioxide. [....] The carbon dioxide is invisible, it is transparent, you can’t smell it, it is not dangerous to health, so why should one worry about it?

Carbon dioxide has a strange property. It transmits visible light but it absorbs the infrared radiation which is emitted from the earth. Its presence in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect [....] It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York. All the coastal cities would be covered, and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions, I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.

How, precisely, Mr. Dunlop and the rest of the audience reacted is unknown, but it’s hard to imagine this being welcome news. After his talk, Teller was asked to “summarize briefly the danger from increased carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere in this century.” The physicist, as if considering a numerical estimation problem, responded:

At present the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen by 2 per cent over normal. By 1970, it will be perhaps 4 per cent, by 1980, 8 per cent, by 1990, 16 per cent [about 360 parts per million, by Teller’s accounting], if we keep on with our exponential rise in the use of purely conventional fuels. By that time, there will be a serious additional impediment for the radiation leaving the earth. Our planet will get a little warmer. It is hard to say whether it will be 2 degrees Fahrenheit or only one or 5.

But when the temperature does rise by a few degrees over the whole globe, there is a possibility that the icecaps will start melting and the level of the oceans will begin to rise. Well, I don’t know whether they will cover the Empire State Building or not, but anyone can calculate it by looking at the map and noting that the icecaps over Greenland and over Antarctica are perhaps five thousand feet thick.

And so, at its hundredth birthday party, American oil was warned of its civilization-destroying potential.

Talk about a buzzkill.

How did the petroleum industry respond? Eight years later, on a cold, clear day in March, Robert Dunlop walked the halls of the U.S. Congress. The 1967 oil embargo was weeks away, and the Senate was investigating the potential of electric vehicles. Dunlop, testifying now as the Chairman of the Board of the American Petroleum Institute, posed the question, “tomorrow’s car: electric or gasoline powered?” His preferred answer was the latter:

We in the petroleum industry are convinced that by the time a practical electric car can be mass-produced and marketed, it will not enjoy any meaningful advantage from an air pollution standpoint. Emissions from internal-combustion engines will have long since been controlled.

Dunlop went on to describe progress in controlling carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, and hydrocarbon emissions from automobiles. Absent from his list? The pollutant he had been warned of years before: carbon dioxide.

We might surmise that the odorless gas simply passed under Robert Dunlop’s nose unnoticed. But less than a year later, the American Petroleum Institute quietly received a report on air pollution it had commissioned from the Stanford Research Institute, and its warning on carbon dioxide was direct:

Significant temperature changes are almost certain to occur by the year 2000, and these could bring about climatic changes. [...] there seems to be no doubt that the potential damage to our environment could be severe. [...] pollutants which we generally ignore because they have little local effect, CO2 and submicron particles, may be the cause of serious world-wide environmental changes.

Thus, by 1968, American oil held in its hands yet another notice of its products’ world-altering side effects, one affirming that global warming was not just cause for research and concern, but a reality needing corrective action: “Past and present studies of CO2 are detailed,” the Stanford Research Institute advised. “What is lacking, however, is [...] work toward systems in which CO2 emissions would be brought under control.”

This early history illuminates the American petroleum industry’s long-running awareness of the planetary warming caused by its products. Teller’s warning, revealed in documentation I found while searching archives, is another brick in a growing wall of evidence.

In the closing days of those optimistic 1950s, Robert Dunlop may have been one of the first oilmen to be warned of the tragedy now looming before us. By the time he departed this world in 1995, the American Petroleum Institute he once led was denying the climate science it had been informed of decades before, attacking the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and fighting climate policies wherever they arose.

This is a history of choices made, paths not taken, and the fall from grace of one of the greatest enterprises – oil, the “prime mover” – ever to tread the earth. Whether it’s also a history of redemption, however partial, remains to be seen.

American oil’s awareness of global warming – and its conspiracy of silence, deceit, and obstruction – goes further than any one company. It extends beyond (though includes) ExxonMobil. The industry is implicated to its core by the history of its largest representative, the American Petroleum Institute.

It is now too late to stop a great deal of change to our planet’s climate and its global payload of disease, destruction, and death. But we can fight to halt climate change as quickly as possible, and we can uncover the history of how we got here. There are lessons to be learned, and there is justice to be served.

Ladies and gentlemen, I am to talk to you about energy in the future. I will start by telling you why I believe that the energy resources of the past must be supplemented. First of all, these energy resources will run short as we use more and more of the fossil fuels. But I would [...] like to mention another reason why we probably have to look for additional fuel supplies. And this, strangely, is the question of contaminating the atmosphere. [....] Whenever you burn conventional fuel, you create carbon dioxide. [....] The carbon dioxide is invisible, it is transparent, you can’t smell it, it is not dangerous to health, so why should one worry about it?

Carbon dioxide has a strange property. It transmits visible light but it absorbs the infrared radiation which is emitted from the earth. Its presence in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect [....] It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York. All the coastal cities would be covered, and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions, I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.

How, precisely, Mr. Dunlop and the rest of the audience reacted is unknown, but it’s hard to imagine this being welcome news. After his talk, Teller was asked to “summarize briefly the danger from increased carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere in this century.” The physicist, as if considering a numerical estimation problem, responded:

At present the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen by 2 per cent over normal. By 1970, it will be perhaps 4 per cent, by 1980, 8 per cent, by 1990, 16 per cent [about 360 parts per million, by Teller’s accounting], if we keep on with our exponential rise in the use of purely conventional fuels. By that time, there will be a serious additional impediment for the radiation leaving the earth. Our planet will get a little warmer. It is hard to say whether it will be 2 degrees Fahrenheit or only one or 5.

But when the temperature does rise by a few degrees over the whole globe, there is a possibility that the icecaps will start melting and the level of the oceans will begin to rise. Well, I don’t know whether they will cover the Empire State Building or not, but anyone can calculate it by looking at the map and noting that the icecaps over Greenland and over Antarctica are perhaps five thousand feet thick.

And so, at its hundredth birthday party, American oil was warned of its civilization-destroying potential.

Talk about a buzzkill.

How did the petroleum industry respond? Eight years later, on a cold, clear day in March, Robert Dunlop walked the halls of the U.S. Congress. The 1967 oil embargo was weeks away, and the Senate was investigating the potential of electric vehicles. Dunlop, testifying now as the Chairman of the Board of the American Petroleum Institute, posed the question, “tomorrow’s car: electric or gasoline powered?” His preferred answer was the latter:

We in the petroleum industry are convinced that by the time a practical electric car can be mass-produced and marketed, it will not enjoy any meaningful advantage from an air pollution standpoint. Emissions from internal-combustion engines will have long since been controlled.

Dunlop went on to describe progress in controlling carbon monoxide, nitrous oxide, and hydrocarbon emissions from automobiles. Absent from his list? The pollutant he had been warned of years before: carbon dioxide.

We might surmise that the odorless gas simply passed under Robert Dunlop’s nose unnoticed. But less than a year later, the American Petroleum Institute quietly received a report on air pollution it had commissioned from the Stanford Research Institute, and its warning on carbon dioxide was direct:

Significant temperature changes are almost certain to occur by the year 2000, and these could bring about climatic changes. [...] there seems to be no doubt that the potential damage to our environment could be severe. [...] pollutants which we generally ignore because they have little local effect, CO2 and submicron particles, may be the cause of serious world-wide environmental changes.