TO COMMENT CLICK HERE

GESTAPO USA

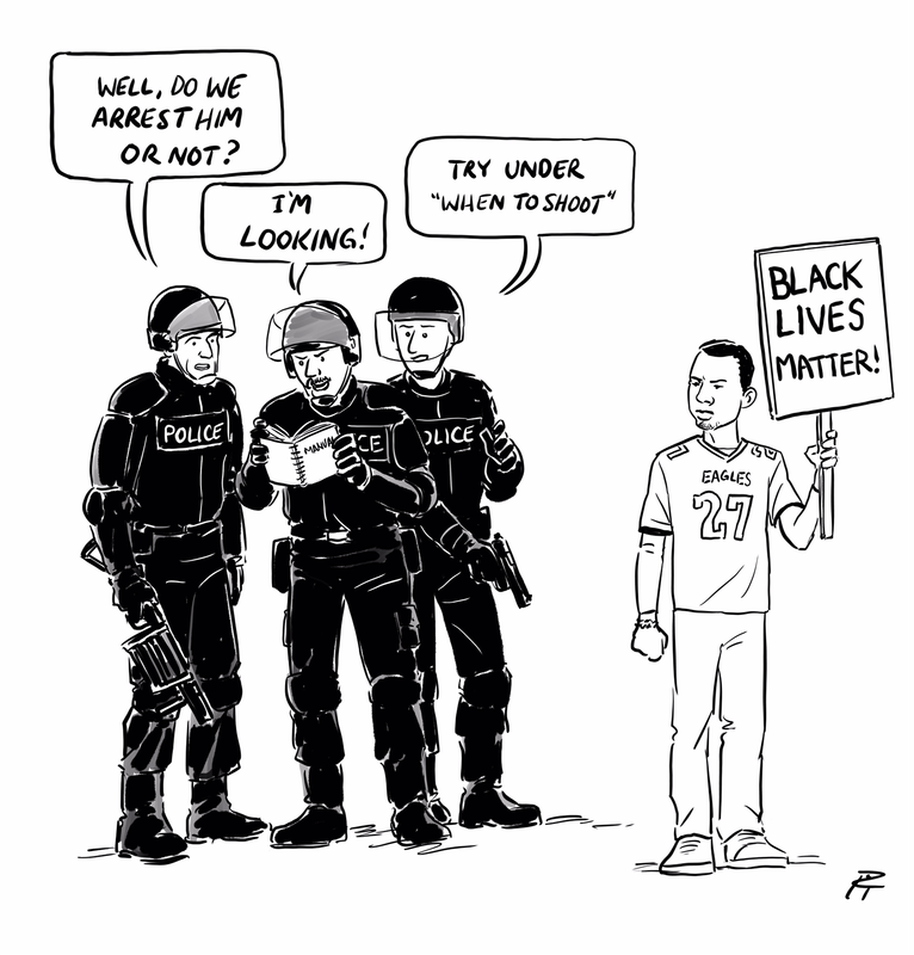

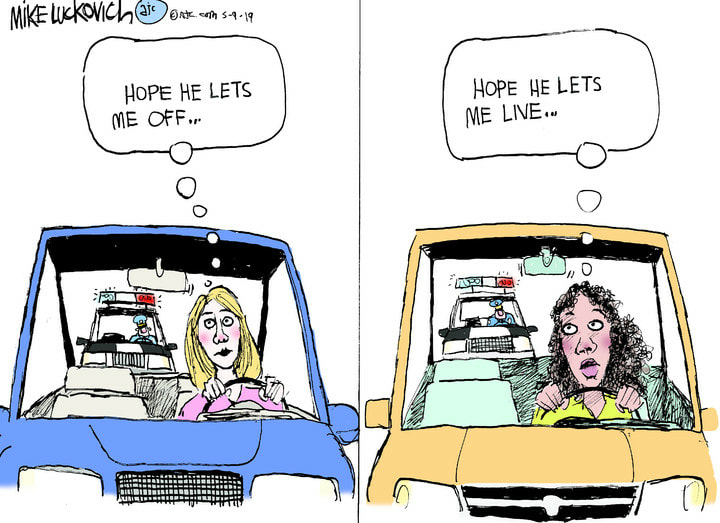

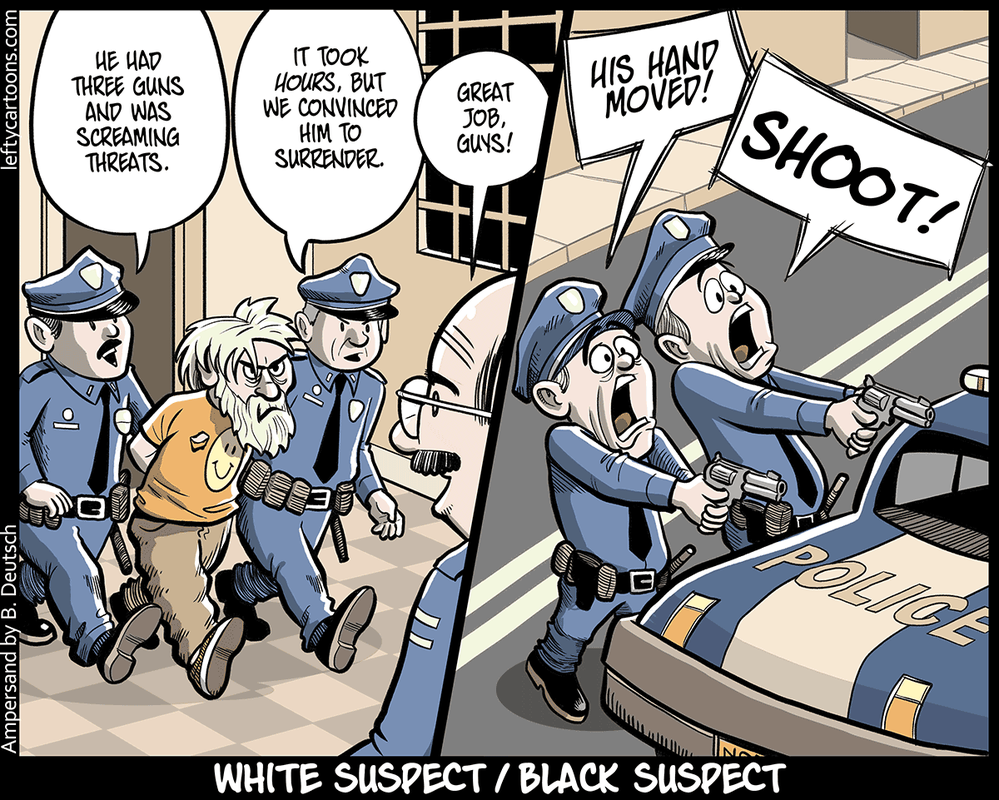

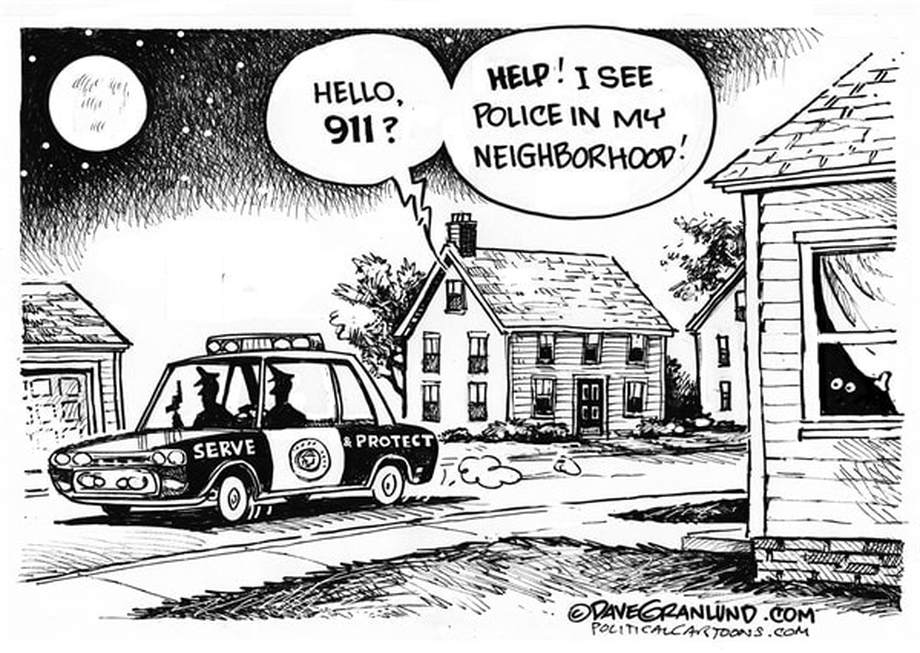

TO SERVE AND PROTECT SOME OF US

january 2024

MICHAEL WOOD: We have a culture that from the beginning has been disproportionate and been oppressive to persons of color, and women, and other minorities. We have a system in which criminal justice is an oxymoron. We have a society that trumps up the second amendment as this big right that we have and that right is to have this weaponry so cops can be killed. That’s literally the purpose of the second amendment. And we have state sanctioned murder all over the country with a blue wall of silence and justice not being done. So I’m completely baffled by why anyone is surprised by all of this.

Why Cops Kill Black People: Research Suggests a Troubling Pattern of 'Retaliatory Violence'

Chauncey DeVega / Salon

The story of race in America is a story of change, and a story of things remaining the same. To measure our progress, or lack thereof, all we need to do is to look at how America's police treat the public, and look in turn at who fills the prison cells -- and all too often the cemeteries.

in the headlines

2023 SAW RECORD KILLINGS BY US POLICE. WHO IS MOST IMPACTED?

(ARTICLE BELOW)

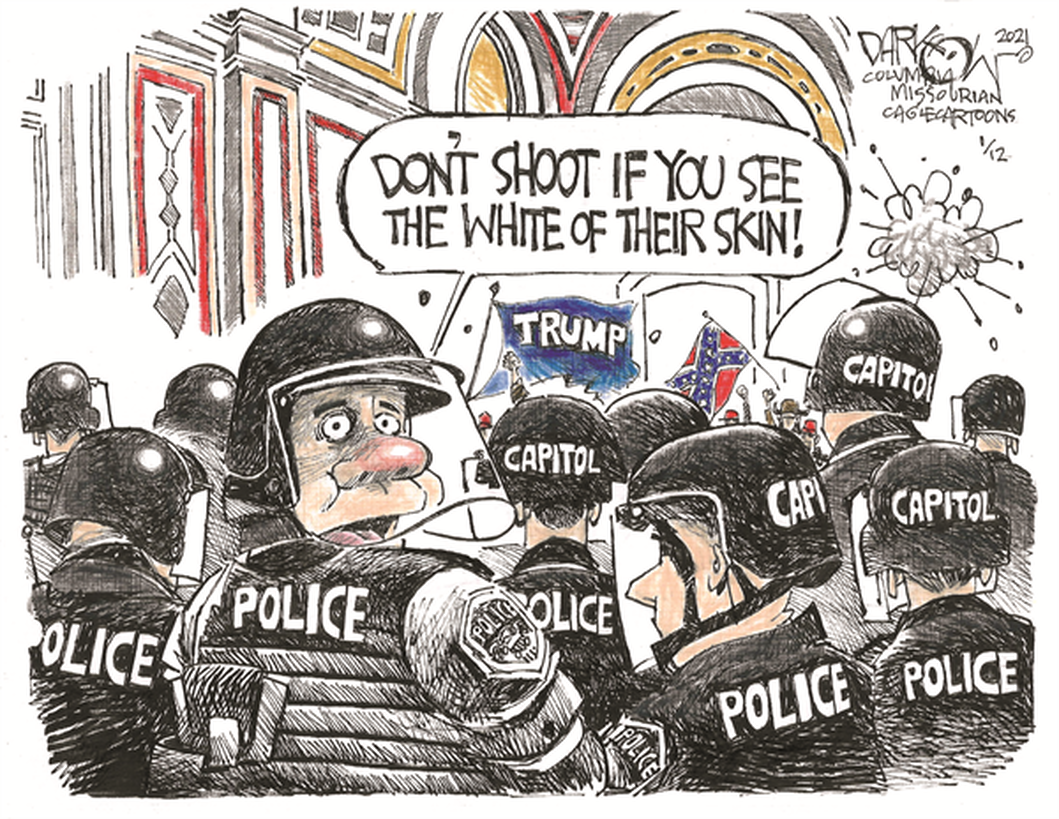

FBI FAILED 'AT FUNDAMENTAL LEVEL' BEFORE CAPITOL RIOT, SENATE REPORT CLAIMS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

WEST VIRGINIA STATE POLICE FACE DAMNING CLAIMS: ‘THE MORE WE DUG, THE WORSE IT STUNK’

(ARTICLE BELOW)

RESEARCH SHOWS THAT ARRESTS FOR SERIOUS CRIMES ARE QUITE RARE.

POLICE SOLVE JUST 2% OF ALL MAJOR CRIMES(ARTICLE BELOW)

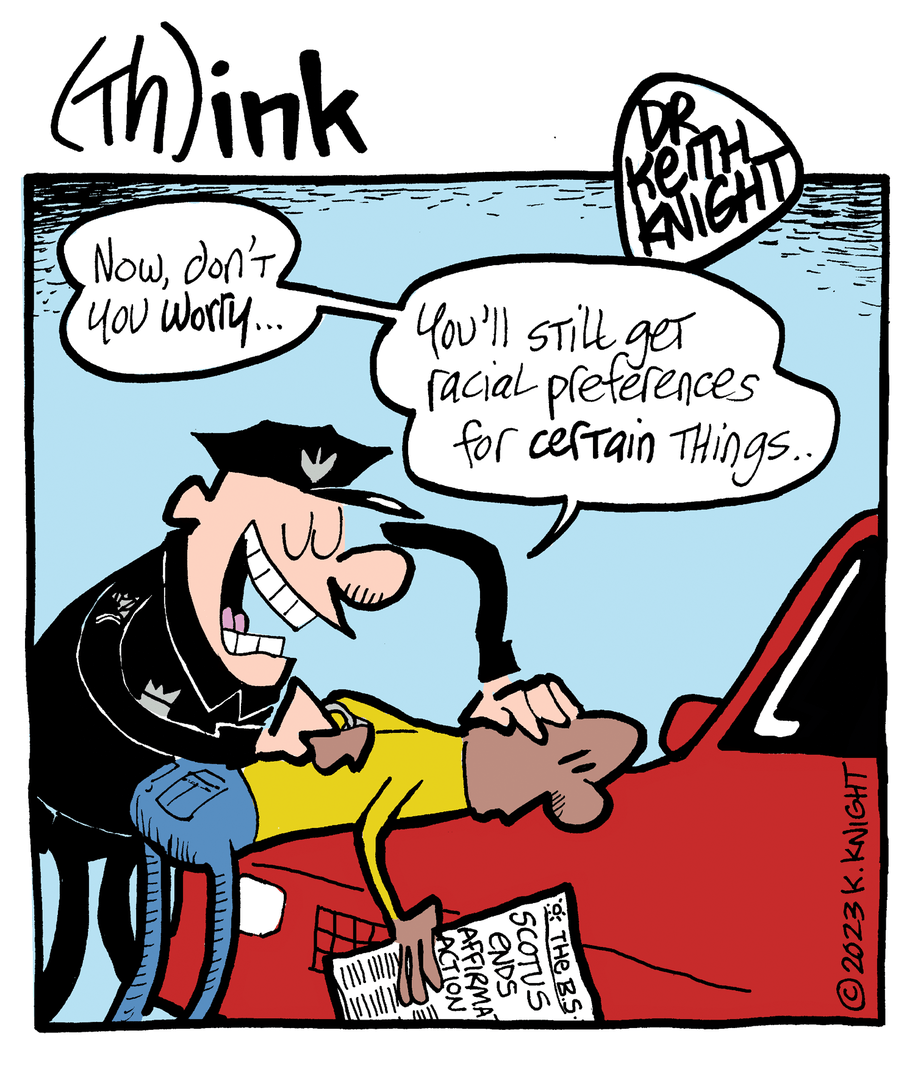

*POLICE RIP BLACK MAN'S PROSTHETIC LEG OFF DURING VIOLENT TRAFFIC STOP: 'IT'S LIKE SOMEONE RIPPING OFF YOUR SKIN'(ARTICLE BELOW)

*HISTORIAN: BLACK DISTRUST OF THE POLICE IS ABOUT MORE THAN ACTS OF VIOLENCE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*‘In a Defenseless Position’: South Carolina Cop Charged After Stomping Black Man’s Head Into Concrete Thanks to 911 Caller Mistaking the Man’s Stick for a Weapon

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*5 police officers face criminal charges in hotel beating of Black men

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*NEW REPORT FINDS POLICE-PERPETRATED KILLINGS IN 2020 WERE VASTLY UNDERREPORTED

(ARTICLE BELOW)

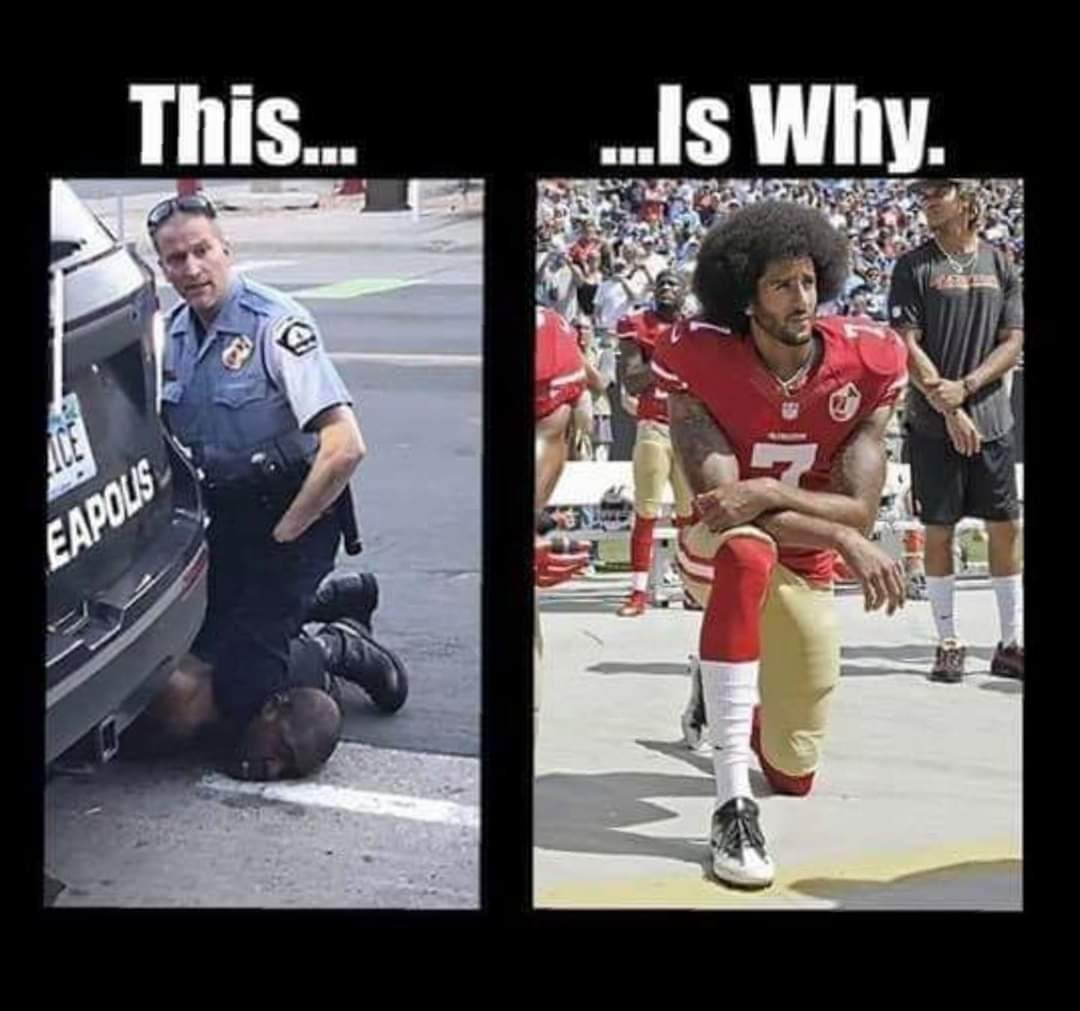

*PRO-COP PAC TRIED TO FUNDRAISE BY BLAMING GEORGE FLOYD FOR HIS OWN DEATH

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*CALLING CHAUVIN A “BAD APPLE” DENIES SYSTEMIC NATURE OF RACIST POLICE VIOLENCE

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*THE LITTLE KNOWN, RACIST HISTORY OF THE 911 EMERGENCY CALL SYSTEM

(ARTICLE BELOW)

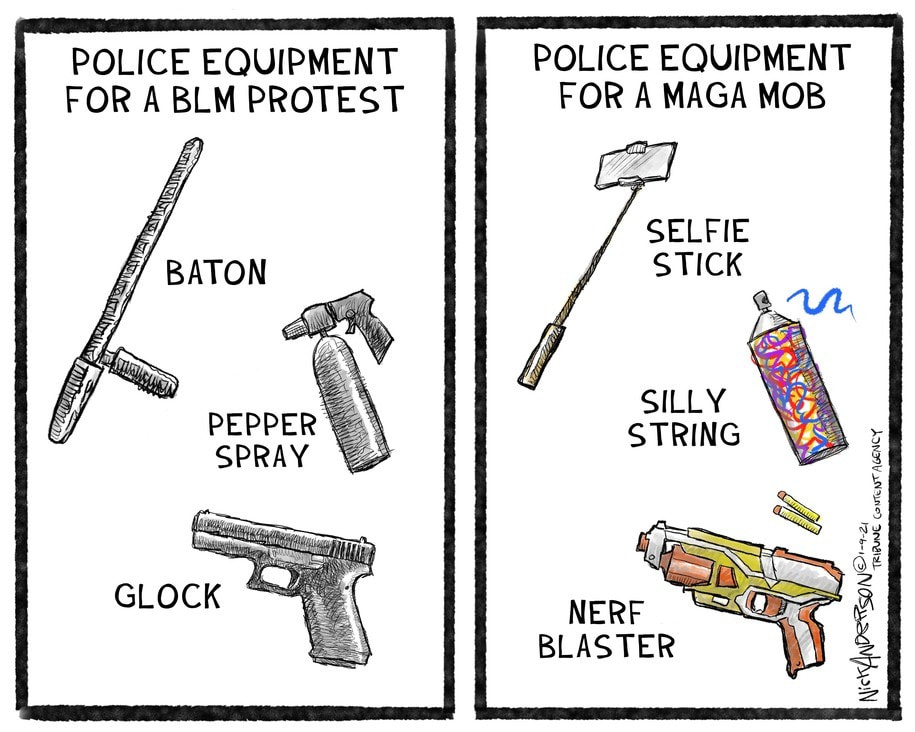

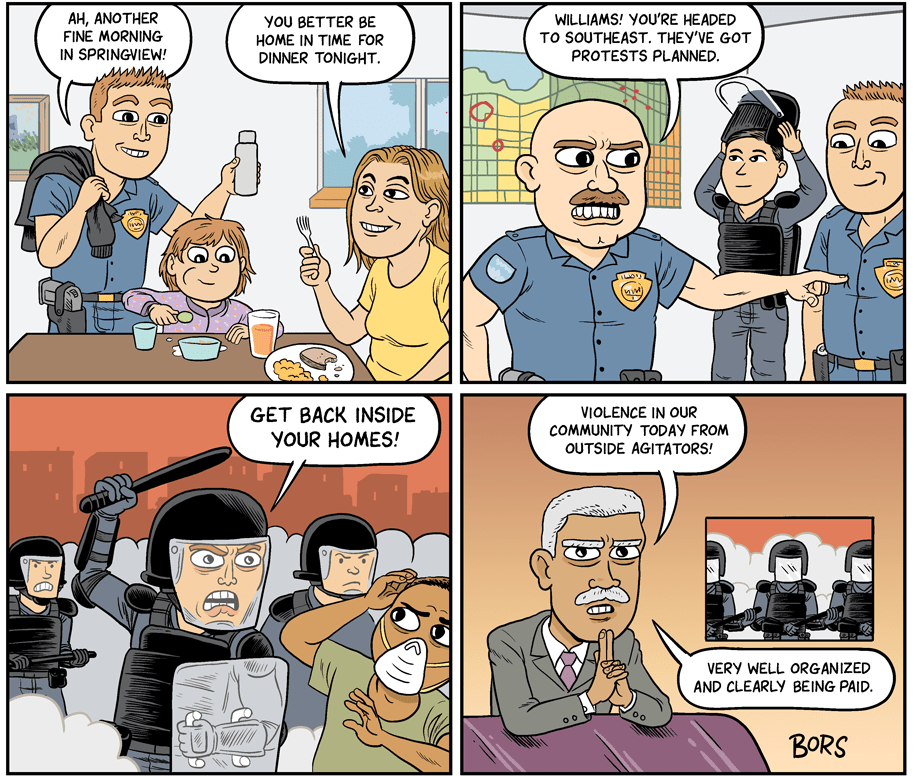

*POLICE ARE 3 TIMES MORE LIKELY TO USE VIOLENCE AGAINST LEFTIST PROTESTERS THAN FAR-RIGHT: ANALYSIS(ARTICLE BELOW)

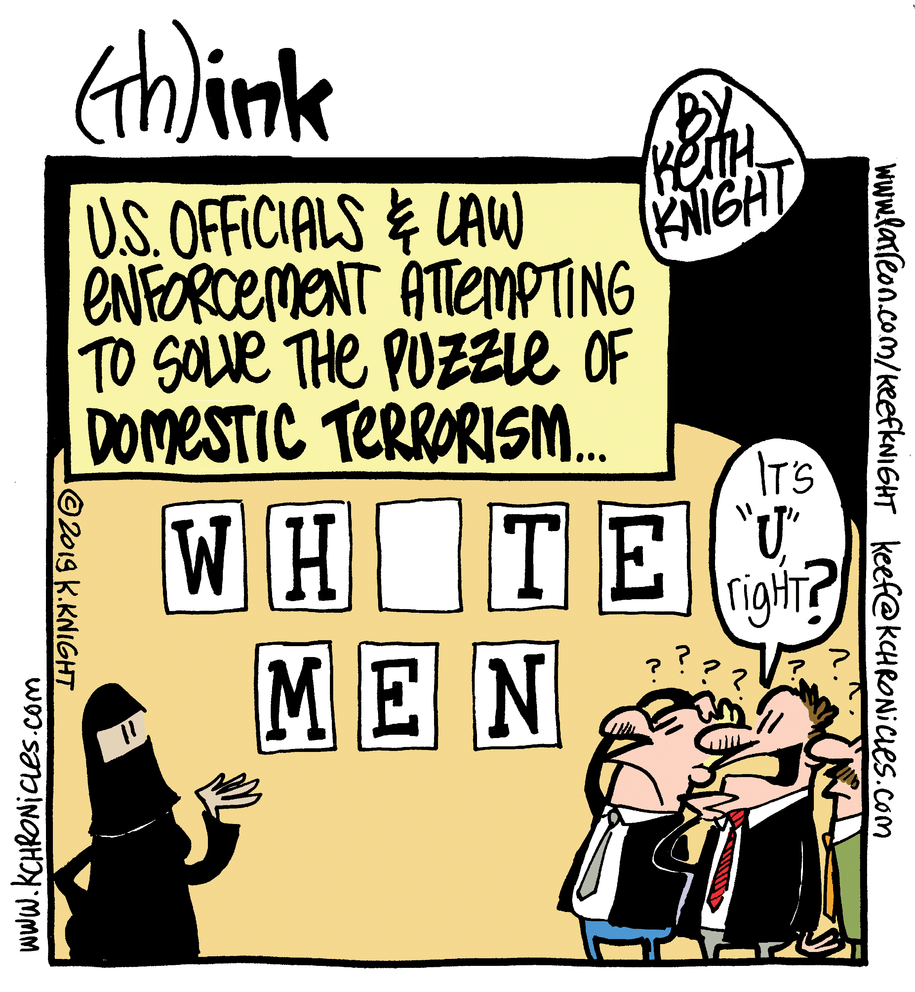

*UNREDACTED FBI DOCUMENT SHEDS NEW LIGHT ON WHITE SUPREMACIST INFILTRATION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT(ARTICLE BELOW)

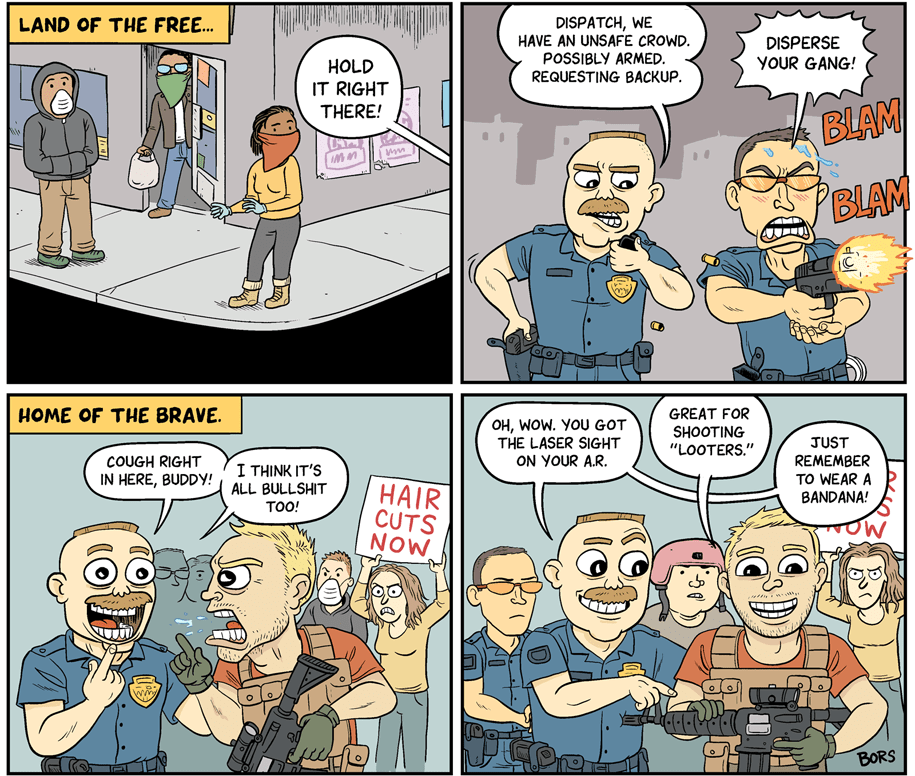

*US Cops Are Treating White Militias as “Heavily Armed Friendlies”

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*MULTIPLE BOSTON COPS ARRESTED FOR ‘STEALING TAXPAYER MONEY’ OVER THE COURSE OF SEVERAL YEARS(ARTICLE BELOW)

*WHITE SUPREMACISTS AND MILITIAS HAVE INFILTRATED POLICE ACROSS US, REPORT SAYS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Cops unleash dog on Black man even though he was kneeling with his hands up

(ARTICLE BELOW)

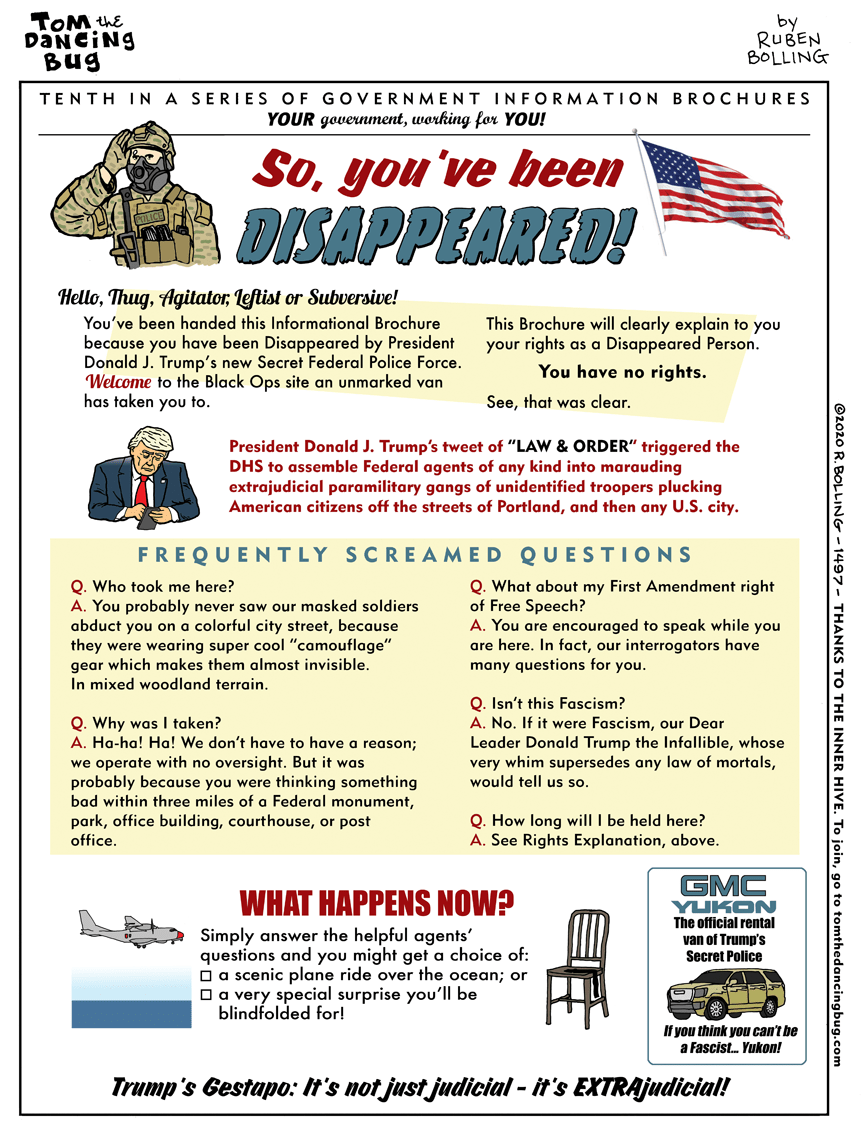

*NYPD admits it’s used unmarked vehicles to apprehend suspects for “decades” after “disturbing” video(ARTICLE BELOW)

*NYPD DISAPPEARED BLACK LIVES MATTER PROTESTERS INTO DETENTION FOR DAYS AT A TIME. LAWMAKERS WANT TO END THE PRACTICE.(ARTICLE BELOW)

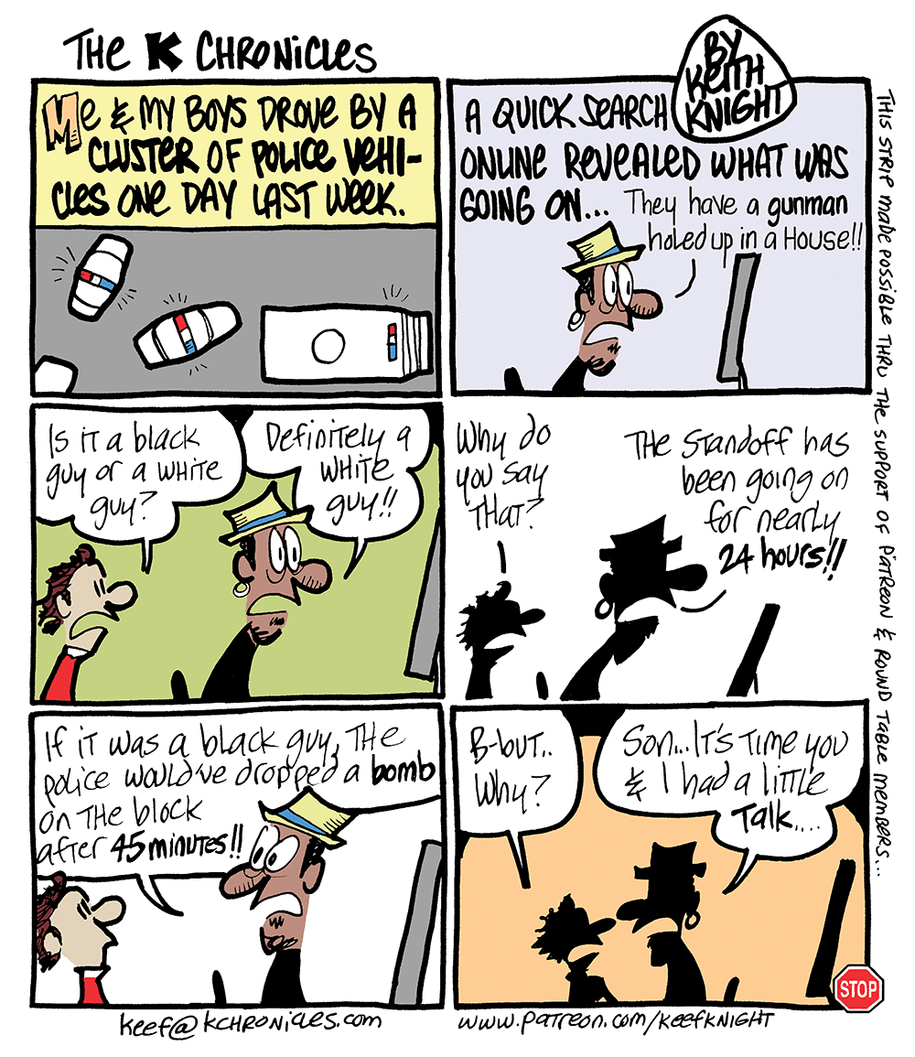

*The psychology of police violence: What makes so many cops have racial biases?

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Cop fired after racist remarks caught on tape “forgot” to disclose criminal record to department(ARTICLE BELOW)

*How Starbucks, Target, Google and Microsoft quietly fund police through private donations(ARTICLE BELOW)

*A Buffalo police officer says she stopped a fellow cop's chokehold on a black suspect. She was fired.(ARTICLE BELOW)

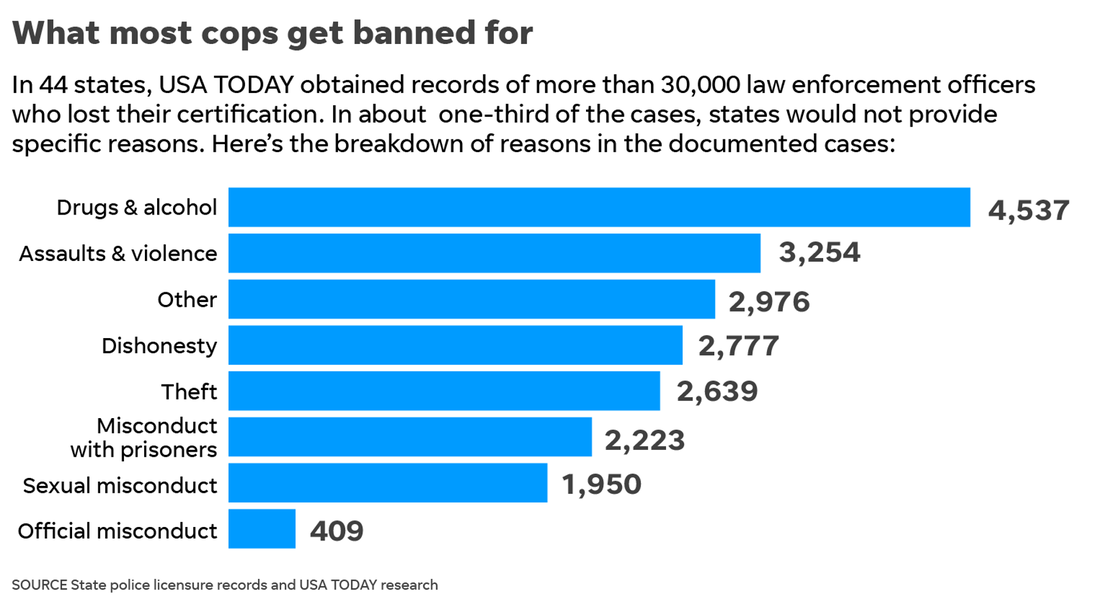

*We found 85,000 cops who’ve been investigated for misconduct. Now you can read their records.(excerpt below)

*Police Are Building Surveillance Networks of Private Security Cameras in Cities

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*If you’re surprised by how the police are acting, you don’t understand US history

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*US POLICE HAVE A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE AGAINST BLACK PEOPLE. WILL IT EVER STOP?

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Suspected Looter Was Kneeling and Had a Hammer, Not a Gun, When Fatally Shot By Vallejo Police(ARTICLE BELOW)

*LOUISVILLE POLICE LEFT THE BODY OF DAVID MCATEE ON THE STREET FOR 12 HOURS

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Policing in the US is not about enforcing law. It’s about enforcing white supremacy

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Police officer: It’s ‘unfortunate’ not all Black people were killed by coronavirus

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*Early Data Shows Black People Are Being Disproportionally Arrested for Social Distancing Violations(ARTICLE BELOW)

*California City Was Accused of Police Brutality Weeks Before Cop Beat Black Teen

(ARTICLE BELOW)

*The racist roots of American policing: From slave patrols to traffic stops

(ARTICLE BELOW)

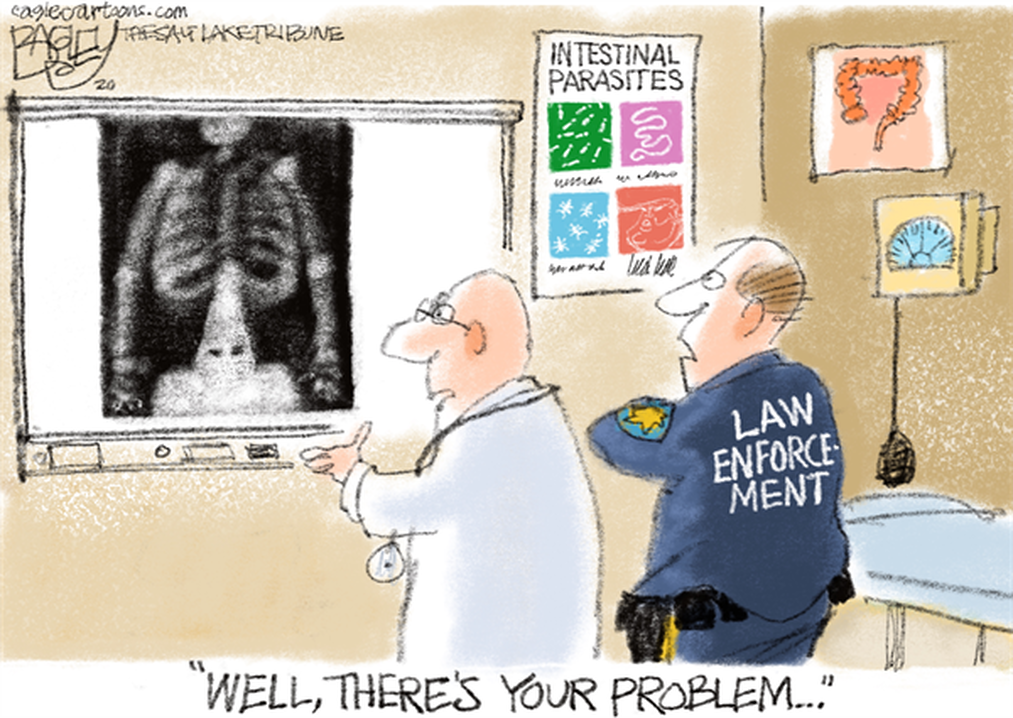

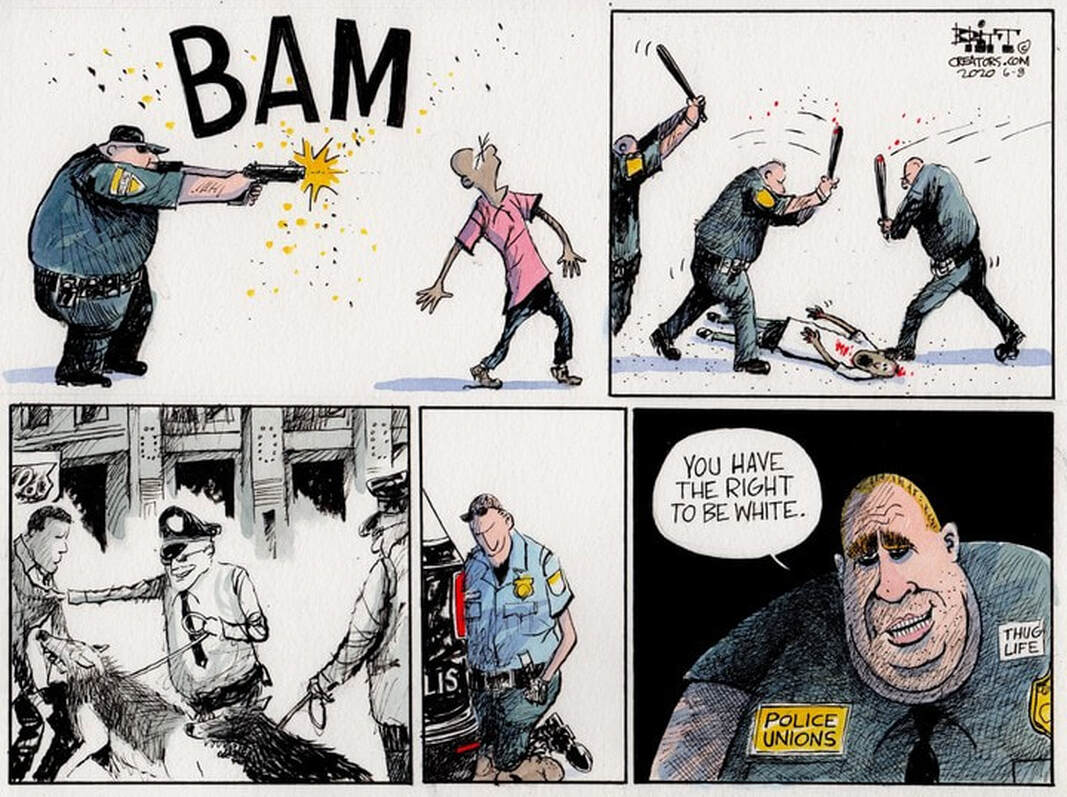

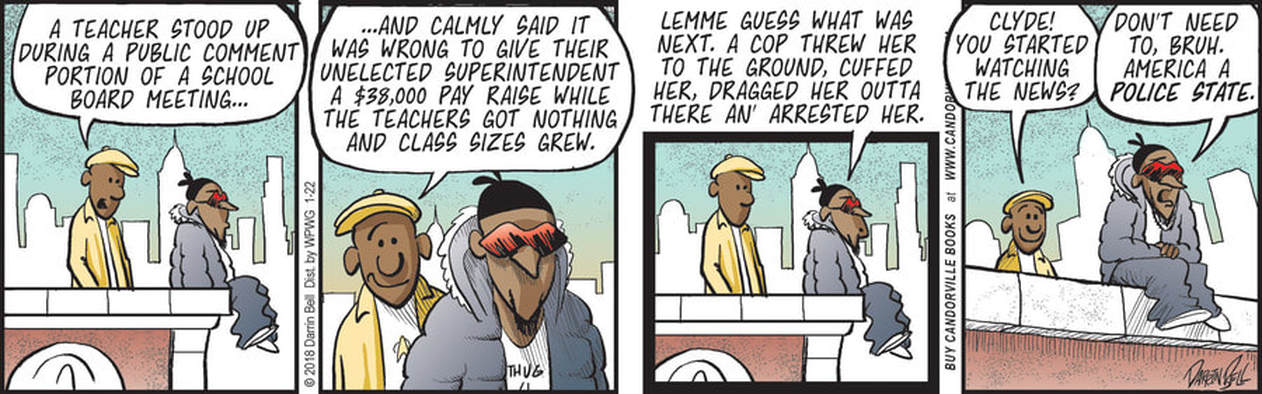

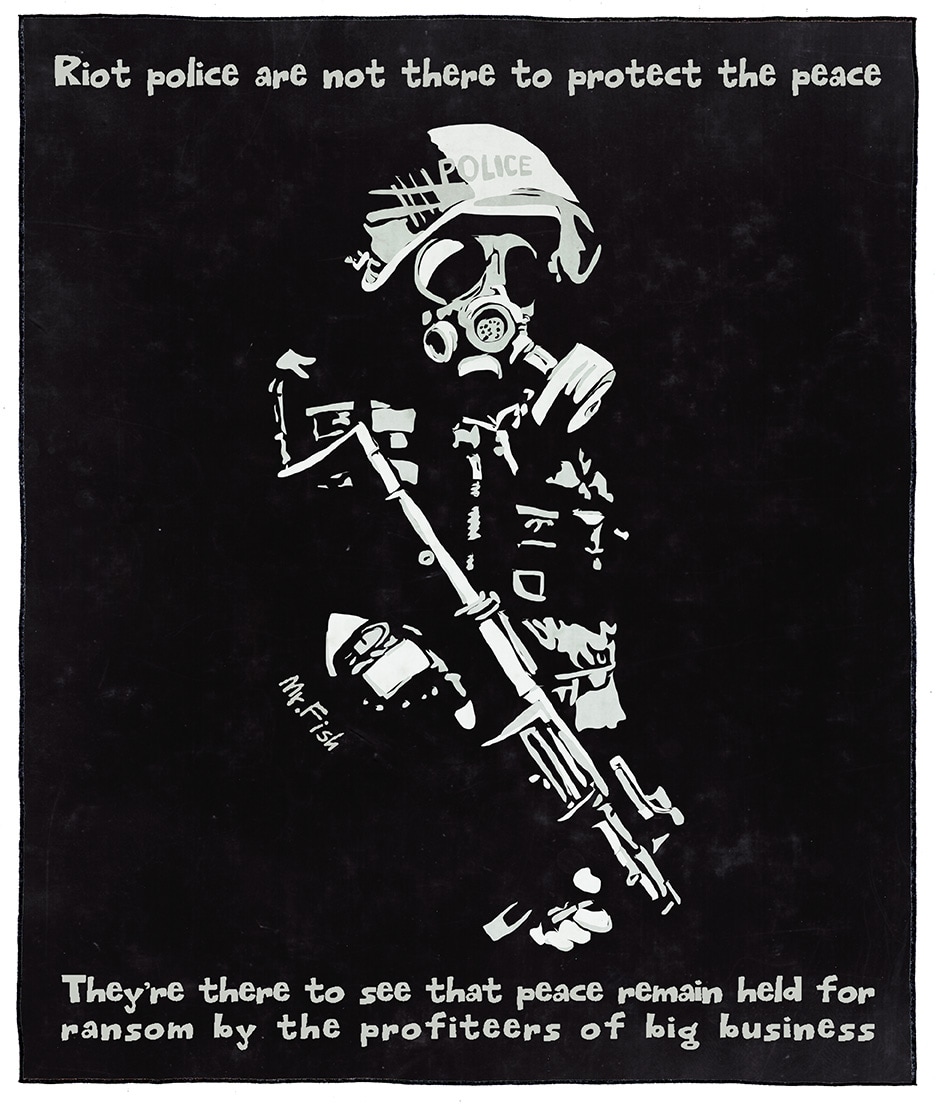

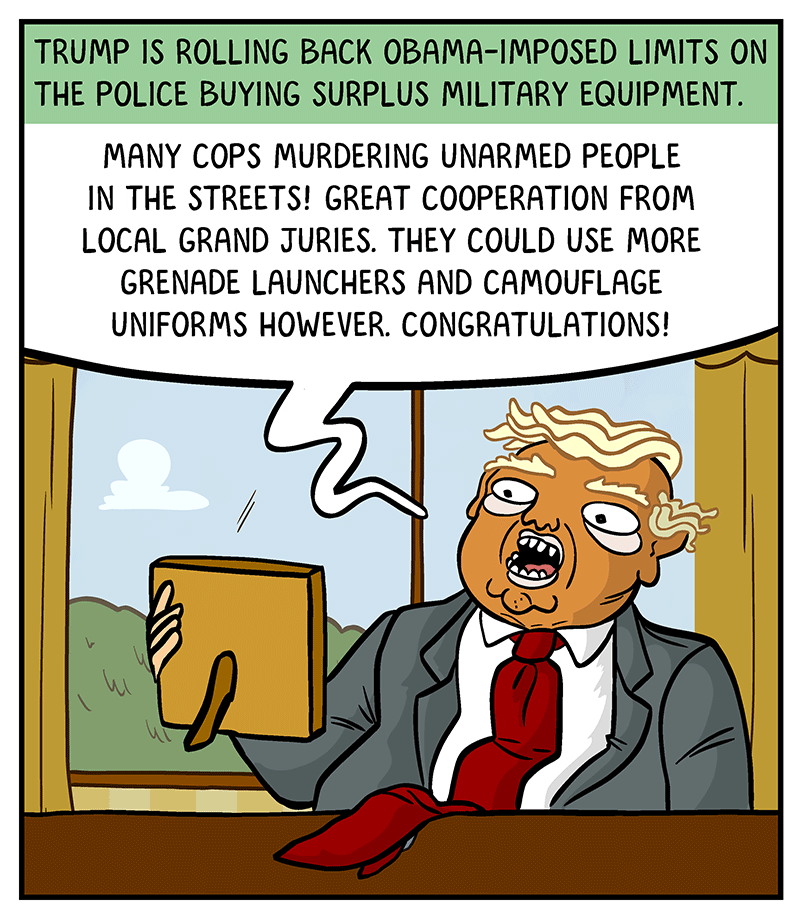

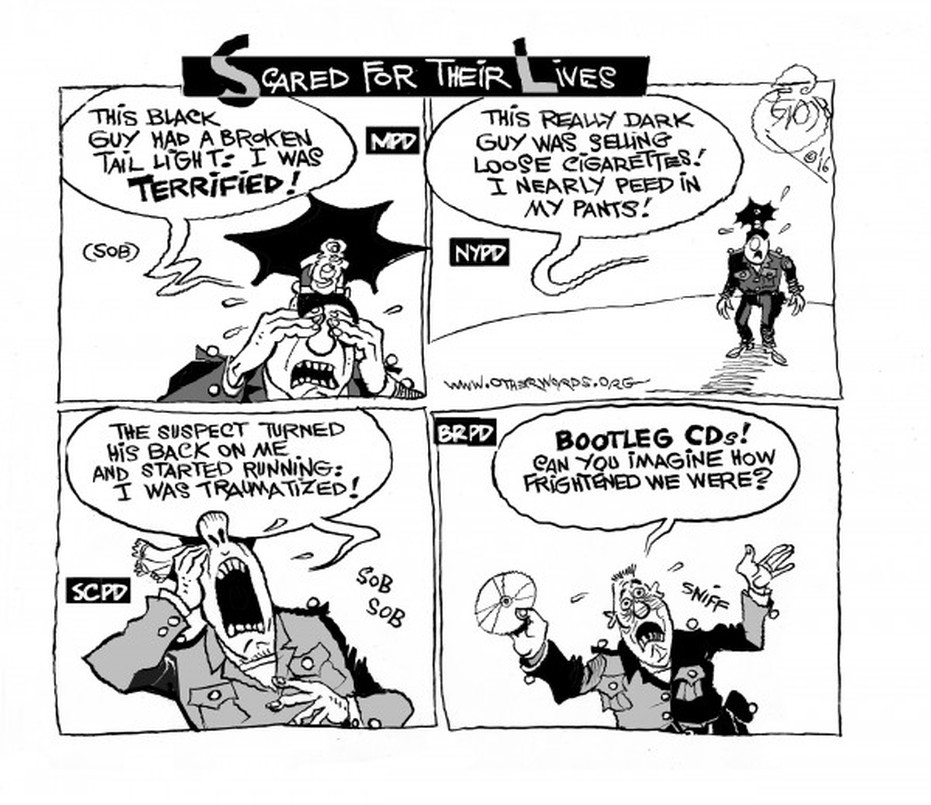

*GESTAPO USA FUNNIES(below)

US policing

2023 saw record killings by US police. Who is most impacted?

Officers killed at least 1,232 people last year – the deadliest year for homicides by law enforcement in over a decade, data shows

Sam Levin in Los Angeles

the guardian

Mon 8 Jan 2024 10.00 EST

Police in the US killed at least 1,232 people last year, making 2023 the deadliest year for homicides committed by law enforcement in more than a decade, according to newly released data.

Mapping Police Violence, a non-profit research group, catalogs deaths at the hands of police and last year recorded the highest number of killings since its national tracking began in 2013. The data suggests a systemic crisis and a remarkably consistent pattern, with an average of roughly three people killed by officers each day, with slight upticks in recent years.

The group recorded 30 more deaths in 2023 than the previous year, with 1,202 people killed in 2022; 1,148 in 2021; 1,160 in 2020; and 1,098 in 2019. The numbers include shooting victims, as well as people fatally shocked by a stun gun, beaten or restrained. The 2023 count is preliminary, and cases could be added as the database is updated.

High-profile 2023 cases included the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols in Memphis; the tasing of Keenan Anderson in Los Angeles; and the shooting in Lancaster, California, of Niani Finlayson, who had called 911 for help from domestic violence. There were hundreds more who garnered little attention, including Ricky Cobb, shot by a Minnesota trooper after he was pulled over for a tail light violation; Tahmon Kenneth Wilson, unarmed and shot outside a Bay Area cannabis dispensary; and Isidra Clara Castillo, killed when police in Amarillo, Texas, fired at someone else in the same car as her.

Here are some key takeaways from the data and experts’ insight into why US police continue to kill civilians at a rate an order of magnitude higher than comparable nations.

Police violence is increasing as murders are falling

The record number of police killings happened in a year that saw a significant decrease in homicides, according to preliminary reports of 2023 murder rates; one analyst said the roughly 13% decrease in homicides last year appears to be the largest year-to-year drop on record, and reports have also signaled drops in other violent and property crimes.

“Violence is trending downwards at an unprecedented rate, but the exception to that seems to be the police, who are engaging in more violence each year,” said Samuel Sinyangwe, a policy analyst and data scientist who founded Mapping Police Violence. “It hits home that many of the promises and actions made after the murder of George Floyd don’t appear to have reduced police violence on a nationwide level.”

Some advocates say the lack of systemic reforms and continued expansion of police forces have helped sustain the high rates. Polls show most Americans believe crime is rising, and amid voter concerns about safety and violence, municipalities have continued to increase police budgets.

Monifa Bandele, an activist on the leadership team for the Movement for Black Lives, said that while state and local governments continue to rely on police to address mental health crises, domestic disputes and other social problems, killings will continue: “The more police you put on the streets to interact with members of my community, the greater the risk of harm, abuse and death.”

Many people were killed while trying to flee police

The circumstances behind the 2023 killings mirrored past trends. Last year, 445 people killed by police had been fleeing, representing 36% of all cases. There have been efforts across the country to prevent police from shooting at fleeing cars and people, recognizing the danger to the public. But the rates have been steady in recent years, with one in three killings involving people fleeing.

The underlying reasons for the encounters were also consistent. In 2023, 139 killings (11%) involved claims a person was seen with a weapon; 107 (9%) began as traffic violations; 100 (8%) were mental health or welfare checks; 79 (6%) were domestic disturbances; 73 (6%) were cases where no offenses were alleged; 265 (22%) involved other alleged nonviolent offenses; and 469 (38%) involved claims of violent offenses or more serious crimes.

“The majority of cases have not originated from reported violent crimes. The police are routinely called into situations where there was no violence until police arrived and the situation escalated,” Sinyangwe said.

Sheriffs’ departments and rural regions are driving the increase

In 2023, there were more killings by police in rural zip codes (319 cases, or 26% of killings) than in urban ones (292 cases, or 24%); the remainder of killings were in suburban areas, with a handful of cases undetermined. This marks a shift from previous years when the number of killings in cities outpaced rural deaths.

County sheriff’s departments, which tend to have jurisdiction over more rural and suburban areas and face less oversight, were responsible for 32% of killings last year; ten years prior, sheriffs were involved in only 26% of killings.

Black Americans were killed at much higher rates

In 2023, Black people were killed at a rate 2.6 times higher than white people, Mapping Police Violence found. Last year, 290 people killed by police were Black, making up 23.5% of victims, while Black Americans make up roughly 14% of the total population. Native Americans were killed at a rate 2.2 times greater than white people, and Latinos were killed at a rate 1.3 times greater.

Black and brown people have also consistently been more likely to be killed while fleeing. From 2013 to 2023, 39% of Black people who were killed by police had been fleeing, typically either running or driving away. That figure is 35% for Latinos, 33% for Native Americans, 29% for white people and 22% for Asian Americans.

Albuquerque and New Mexico had the deadliest rates

Police in New Mexico killed 23 people last year, making it the state with the highest number of fatalities per capita, with a rate of 10.9 killings per 1 million residents, Mapping Police Violence found.

In one New Mexico case in April, Farmington officers showed up to the wrong house and killed the resident, Robert Dotson, when he opened the door with a handgun. In November, an officer in Las Cruces near the border fatally shot Teresa Gomez after he questioned why she was parked outside a public housing complex.

Albuquerque, New Mexico’s most populous city, also ranked highest in killings per capita among the country’s 50 largest cities. Albuquerque police killed six people in 2023, while many cities with substantially larger populations, including San Jose and Honolulu, each killed only one civilian last year. Some advocates have said gun culture in the state, particularly in rural areas, could be a factor in the high rates of police violence.

A spokesperson for New Mexico governor Michelle Lujan Grisham said in an email that she was “committed to promoting professional and constitutional policing”, and noted the governor signed a bill into law last year “aimed at increased accountability for those in this critical profession”. SB19 established a duty to intervene when officers witness certain unlawful uses of force; prohibited neck restraints and firing at fleeing vehicles; and required the establishment of a public police misconduct database.

Spokespeople for Albuquerque police did not respond to an inquiry on Friday.

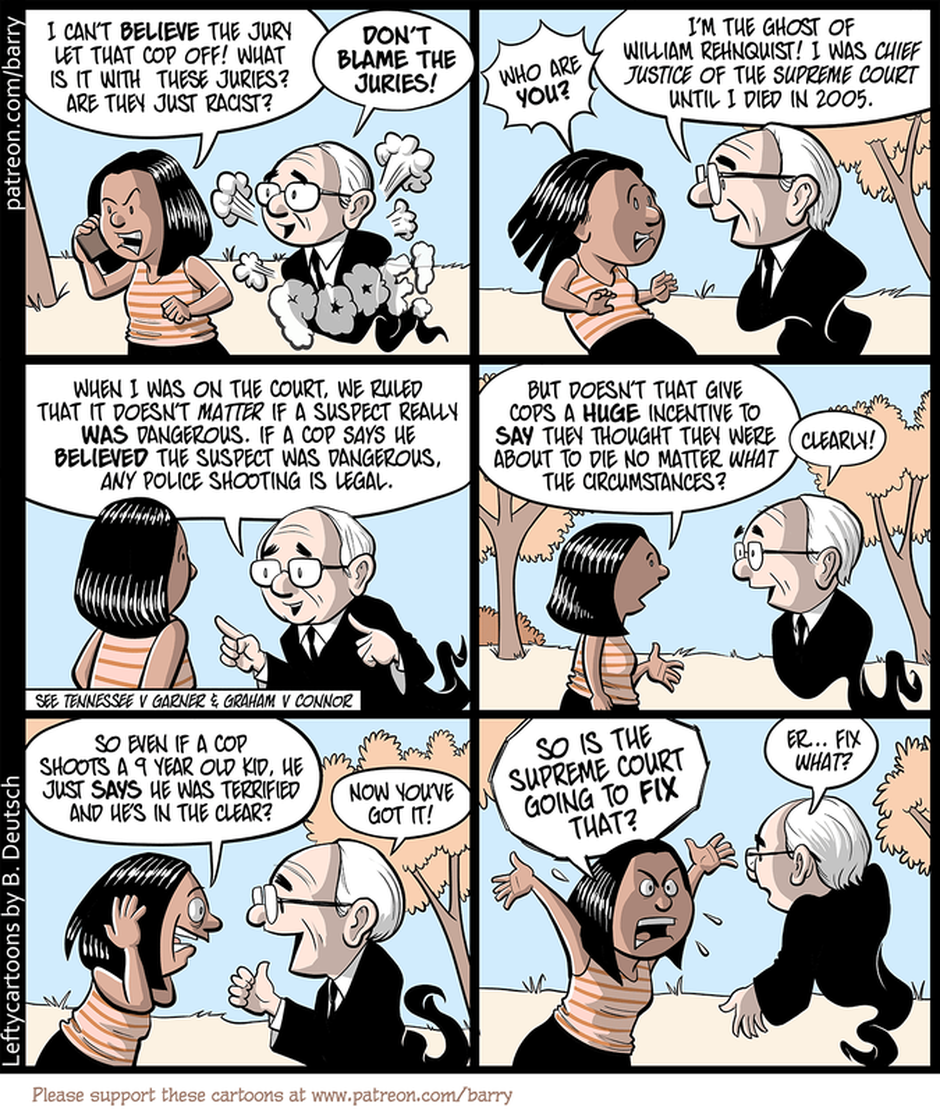

Few officers face accountability

From 2013 to 2022, 98% of police killings have not resulted in officers facing charges, Mapping Police Violence reported.

This contributes to the steady rate of violence, said Joanna Schwartz, University of California, Los Angeles law professor and expert on how officers evade accountability for misconduct:“Even with public attention to police killings in recent years and unprecedented community engagement, it’s really business as usual. That means tremendous discretion given to police to use force whenever they believe it’s appropriate, very limited federal and state oversight of policing, and union agreements across the country that make it very difficult to effectively investigate, discipline or fire officers.”

Problem officers with repeated brutality incidents or killings frequently remain on the force or get jobs in other departments, she noted.

Some cities experienced decreases in lethal force

Some cities with histories of police brutality had notably few killings in 2023. St Louis police killed one person last year, and there were no killings recorded by Minneapolis, Seattle or Boston police.

“It suggests that even places with longstanding issues can see improvement. It’s not fixed that they always have to be this way,” Sinyangwe said.

Bandele noted that there are community violence prevention programs that have helped reduce reliance on police and limit vulnerable people’s exposure to potentially lethal encounters. Denver has received national attention for its program sending civilian responders to mental health calls instead of police. A Brooklyn neighborhood last year experimented with civilian responders to 911 calls.

“Every week, someone who needs mental health care ends up killed by police,” Bandele said. “But there are alternative ways to respond.”

RELATED: How the system shapes "bad apple" cops

Mapping Police Violence, a non-profit research group, catalogs deaths at the hands of police and last year recorded the highest number of killings since its national tracking began in 2013. The data suggests a systemic crisis and a remarkably consistent pattern, with an average of roughly three people killed by officers each day, with slight upticks in recent years.

The group recorded 30 more deaths in 2023 than the previous year, with 1,202 people killed in 2022; 1,148 in 2021; 1,160 in 2020; and 1,098 in 2019. The numbers include shooting victims, as well as people fatally shocked by a stun gun, beaten or restrained. The 2023 count is preliminary, and cases could be added as the database is updated.

High-profile 2023 cases included the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols in Memphis; the tasing of Keenan Anderson in Los Angeles; and the shooting in Lancaster, California, of Niani Finlayson, who had called 911 for help from domestic violence. There were hundreds more who garnered little attention, including Ricky Cobb, shot by a Minnesota trooper after he was pulled over for a tail light violation; Tahmon Kenneth Wilson, unarmed and shot outside a Bay Area cannabis dispensary; and Isidra Clara Castillo, killed when police in Amarillo, Texas, fired at someone else in the same car as her.

Here are some key takeaways from the data and experts’ insight into why US police continue to kill civilians at a rate an order of magnitude higher than comparable nations.

Police violence is increasing as murders are falling

The record number of police killings happened in a year that saw a significant decrease in homicides, according to preliminary reports of 2023 murder rates; one analyst said the roughly 13% decrease in homicides last year appears to be the largest year-to-year drop on record, and reports have also signaled drops in other violent and property crimes.

“Violence is trending downwards at an unprecedented rate, but the exception to that seems to be the police, who are engaging in more violence each year,” said Samuel Sinyangwe, a policy analyst and data scientist who founded Mapping Police Violence. “It hits home that many of the promises and actions made after the murder of George Floyd don’t appear to have reduced police violence on a nationwide level.”

Some advocates say the lack of systemic reforms and continued expansion of police forces have helped sustain the high rates. Polls show most Americans believe crime is rising, and amid voter concerns about safety and violence, municipalities have continued to increase police budgets.

Monifa Bandele, an activist on the leadership team for the Movement for Black Lives, said that while state and local governments continue to rely on police to address mental health crises, domestic disputes and other social problems, killings will continue: “The more police you put on the streets to interact with members of my community, the greater the risk of harm, abuse and death.”

Many people were killed while trying to flee police

The circumstances behind the 2023 killings mirrored past trends. Last year, 445 people killed by police had been fleeing, representing 36% of all cases. There have been efforts across the country to prevent police from shooting at fleeing cars and people, recognizing the danger to the public. But the rates have been steady in recent years, with one in three killings involving people fleeing.

The underlying reasons for the encounters were also consistent. In 2023, 139 killings (11%) involved claims a person was seen with a weapon; 107 (9%) began as traffic violations; 100 (8%) were mental health or welfare checks; 79 (6%) were domestic disturbances; 73 (6%) were cases where no offenses were alleged; 265 (22%) involved other alleged nonviolent offenses; and 469 (38%) involved claims of violent offenses or more serious crimes.

“The majority of cases have not originated from reported violent crimes. The police are routinely called into situations where there was no violence until police arrived and the situation escalated,” Sinyangwe said.

Sheriffs’ departments and rural regions are driving the increase

In 2023, there were more killings by police in rural zip codes (319 cases, or 26% of killings) than in urban ones (292 cases, or 24%); the remainder of killings were in suburban areas, with a handful of cases undetermined. This marks a shift from previous years when the number of killings in cities outpaced rural deaths.

County sheriff’s departments, which tend to have jurisdiction over more rural and suburban areas and face less oversight, were responsible for 32% of killings last year; ten years prior, sheriffs were involved in only 26% of killings.

Black Americans were killed at much higher rates

In 2023, Black people were killed at a rate 2.6 times higher than white people, Mapping Police Violence found. Last year, 290 people killed by police were Black, making up 23.5% of victims, while Black Americans make up roughly 14% of the total population. Native Americans were killed at a rate 2.2 times greater than white people, and Latinos were killed at a rate 1.3 times greater.

Black and brown people have also consistently been more likely to be killed while fleeing. From 2013 to 2023, 39% of Black people who were killed by police had been fleeing, typically either running or driving away. That figure is 35% for Latinos, 33% for Native Americans, 29% for white people and 22% for Asian Americans.

Albuquerque and New Mexico had the deadliest rates

Police in New Mexico killed 23 people last year, making it the state with the highest number of fatalities per capita, with a rate of 10.9 killings per 1 million residents, Mapping Police Violence found.

In one New Mexico case in April, Farmington officers showed up to the wrong house and killed the resident, Robert Dotson, when he opened the door with a handgun. In November, an officer in Las Cruces near the border fatally shot Teresa Gomez after he questioned why she was parked outside a public housing complex.

Albuquerque, New Mexico’s most populous city, also ranked highest in killings per capita among the country’s 50 largest cities. Albuquerque police killed six people in 2023, while many cities with substantially larger populations, including San Jose and Honolulu, each killed only one civilian last year. Some advocates have said gun culture in the state, particularly in rural areas, could be a factor in the high rates of police violence.

A spokesperson for New Mexico governor Michelle Lujan Grisham said in an email that she was “committed to promoting professional and constitutional policing”, and noted the governor signed a bill into law last year “aimed at increased accountability for those in this critical profession”. SB19 established a duty to intervene when officers witness certain unlawful uses of force; prohibited neck restraints and firing at fleeing vehicles; and required the establishment of a public police misconduct database.

Spokespeople for Albuquerque police did not respond to an inquiry on Friday.

Few officers face accountability

From 2013 to 2022, 98% of police killings have not resulted in officers facing charges, Mapping Police Violence reported.

This contributes to the steady rate of violence, said Joanna Schwartz, University of California, Los Angeles law professor and expert on how officers evade accountability for misconduct:“Even with public attention to police killings in recent years and unprecedented community engagement, it’s really business as usual. That means tremendous discretion given to police to use force whenever they believe it’s appropriate, very limited federal and state oversight of policing, and union agreements across the country that make it very difficult to effectively investigate, discipline or fire officers.”

Problem officers with repeated brutality incidents or killings frequently remain on the force or get jobs in other departments, she noted.

Some cities experienced decreases in lethal force

Some cities with histories of police brutality had notably few killings in 2023. St Louis police killed one person last year, and there were no killings recorded by Minneapolis, Seattle or Boston police.

“It suggests that even places with longstanding issues can see improvement. It’s not fixed that they always have to be this way,” Sinyangwe said.

Bandele noted that there are community violence prevention programs that have helped reduce reliance on police and limit vulnerable people’s exposure to potentially lethal encounters. Denver has received national attention for its program sending civilian responders to mental health calls instead of police. A Brooklyn neighborhood last year experimented with civilian responders to 911 calls.

“Every week, someone who needs mental health care ends up killed by police,” Bandele said. “But there are alternative ways to respond.”

RELATED: How the system shapes "bad apple" cops

the incompetence of christopher wray!!!

FBI failed 'at fundamental level' before Capitol riot, Senate report claims

By Gareth Evans - BBC News

6/27/2023

The FBI and other US government agencies failed "at a fundamental level" to assess the potential for violence ahead of the Capitol riot on 6 January 2021, a new report claims.

Democrats on a Senate panel found the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) "downplayed" the risks and so did not properly prepare.

The 105-page report, titled Planned in Plain Sight, was released on Tuesday.

It criticises officials for misjudging and reacting slowly to tip-offs.

"At a fundamental level, the agencies failed to fulfil their mission and connect the public and non-public information they received," the report reads.

It adds that officials from the agencies failed to "formally disseminate guidance to their law enforcement partners with sufficient urgency and alarm to enable those partners to prepare for the violence that ultimately occurred".

The report offers specific examples of the type of warnings the FBI received, including flagged online extremist activity, public tip-offs and alerts from its own field offices around the country.

One example the report highlights is a social media post on the Parler platform directed at the FBI four days before the riot. "This is a final stand where we are drawing the red line at Capitol Hill," it reads. "Don't be surprised if we take the #capital building."

Many other posts alluded to a potential violent attack on the Capitol, the report by Democrats on the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee suggests.

The document also includes a previously unknown warning from the FBI's New Orleans office which was issued on 5 January 2021. It said some people who were planning to attend the protest in Washington the following day were planning to be armed.

"What was shocking is that this attack was essentially planned in plain sight in social media," the committee's Democratic chair, Gary Peters, said. "And yet it seemed as if our intelligence agencies completely dropped the ball."

In a statement, an FBI spokesperson said the bureau was "constantly trying to learn and evaluate what we can do better or differently, and this is especially true of the attack on the US Capitol".

The spokesman added that, since the attack, the bureau had centralised the flow of information to ensure timely threat notifications to all field offices.

Separately, a spokesperson for the DHS told the Washington Post that the agency had been conducting a "comprehensive organisational review" which would soon develop recommendations.

The 6 January riot saw more than 2,000 people enter the US Capitol as lawmakers certified the results of the 2020 election, in which President Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump.

The mob stormed the Capitol following a speech from Mr Trump, who was speaking at a rally not far from the Capitol grounds. In his speech, Mr Trump claimed election fraud and called on then-Vice-President Mike Pence to overturn the results.

The riot led to the biggest police investigation in US history with hundreds of people accused of criminal offences.

Democrats on a Senate panel found the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) "downplayed" the risks and so did not properly prepare.

The 105-page report, titled Planned in Plain Sight, was released on Tuesday.

It criticises officials for misjudging and reacting slowly to tip-offs.

"At a fundamental level, the agencies failed to fulfil their mission and connect the public and non-public information they received," the report reads.

It adds that officials from the agencies failed to "formally disseminate guidance to their law enforcement partners with sufficient urgency and alarm to enable those partners to prepare for the violence that ultimately occurred".

The report offers specific examples of the type of warnings the FBI received, including flagged online extremist activity, public tip-offs and alerts from its own field offices around the country.

One example the report highlights is a social media post on the Parler platform directed at the FBI four days before the riot. "This is a final stand where we are drawing the red line at Capitol Hill," it reads. "Don't be surprised if we take the #capital building."

Many other posts alluded to a potential violent attack on the Capitol, the report by Democrats on the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee suggests.

The document also includes a previously unknown warning from the FBI's New Orleans office which was issued on 5 January 2021. It said some people who were planning to attend the protest in Washington the following day were planning to be armed.

"What was shocking is that this attack was essentially planned in plain sight in social media," the committee's Democratic chair, Gary Peters, said. "And yet it seemed as if our intelligence agencies completely dropped the ball."

In a statement, an FBI spokesperson said the bureau was "constantly trying to learn and evaluate what we can do better or differently, and this is especially true of the attack on the US Capitol".

The spokesman added that, since the attack, the bureau had centralised the flow of information to ensure timely threat notifications to all field offices.

Separately, a spokesperson for the DHS told the Washington Post that the agency had been conducting a "comprehensive organisational review" which would soon develop recommendations.

The 6 January riot saw more than 2,000 people enter the US Capitol as lawmakers certified the results of the 2020 election, in which President Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump.

The mob stormed the Capitol following a speech from Mr Trump, who was speaking at a rally not far from the Capitol grounds. In his speech, Mr Trump claimed election fraud and called on then-Vice-President Mike Pence to overturn the results.

The riot led to the biggest police investigation in US history with hundreds of people accused of criminal offences.

GESTAPO USA!!!

West Virginia state police face damning claims: ‘The more we dug, the worse it stunk’

An anonymous letter detailed abuses including hidden cameras, theft, kidnapping, druggings and rape – and their cover-up

Maya Yang - THE GUARDIAN

Mon 26 Jun 2023 08.00 EDT

A slew of investigations have opened up against the West Virginia state police department after startling claims surfaced in recent months including alleged hidden cameras in women’s locker rooms, casino thefts, cover-ups, kidnappings, druggings and rape.

The investigations were initiated after an anonymous five-page letter was sent to multiple state lawmakers. The contents of the letter, which were then covered by local media outlets, consisted of multiple damning claims. Those claims triggered leadership changes across the department as well as sweeping investigations into the West Virginia state police.

In February, local reports emerged of the letter that was sent to a handful of the state’s highest-ranking politicians, including the governor, Jim Justice, and the attorney general, Patrick Morrisey. The letter’s allegations ranged from misuse of state and federal dollars, office affairs, illegal overtime practices, drunken fights, hidden cameras and sexual assault.

“The more we dug, the worse it stunk,” Justice said about the allegations in March. He subsequently ordered the state’s department of homeland security, as well as the interim superintendent of the West Virginia state police, Jack Chambers, to launch a multipronged investigation into the alleged wrongdoings.

One of the most disturbing claims involves at least one alleged hidden camera that was placed in the women’s locker room at the West Virginia state police academy. On 23 March, attorney Teresa Toriseva filed the first of four notices of legal action to Morrisey and Chambers, who replaced former superintendent Jan Cahill after his resignation in March.

Two retired West Virginia state police uniformed employees and a civilian, who regularly used the women’s locker room throughout their careers and after their retirements, intended to sue the West Virginia state police after media reported on the alleged hidden camera, according to the letter reviewed by the Guardian.

On 16 June, in her fourth and final notice of legal action, Toriseva revealed that her law office has gone from representing three women to 67, all of whom will be “filing claims against the West Virginia State Police for creating a toxic and hostile environment”.

In addition to the dozens of women who attended or visited the academy from 1994 to the present day, there were at least 10 minors likely between the ages of 14 and 17 who were part of the state police’s Junior Trooper academy and used the locker room, the letter said.

The investigations were initiated after an anonymous five-page letter was sent to multiple state lawmakers. The contents of the letter, which were then covered by local media outlets, consisted of multiple damning claims. Those claims triggered leadership changes across the department as well as sweeping investigations into the West Virginia state police.

In February, local reports emerged of the letter that was sent to a handful of the state’s highest-ranking politicians, including the governor, Jim Justice, and the attorney general, Patrick Morrisey. The letter’s allegations ranged from misuse of state and federal dollars, office affairs, illegal overtime practices, drunken fights, hidden cameras and sexual assault.

“The more we dug, the worse it stunk,” Justice said about the allegations in March. He subsequently ordered the state’s department of homeland security, as well as the interim superintendent of the West Virginia state police, Jack Chambers, to launch a multipronged investigation into the alleged wrongdoings.

One of the most disturbing claims involves at least one alleged hidden camera that was placed in the women’s locker room at the West Virginia state police academy. On 23 March, attorney Teresa Toriseva filed the first of four notices of legal action to Morrisey and Chambers, who replaced former superintendent Jan Cahill after his resignation in March.

Two retired West Virginia state police uniformed employees and a civilian, who regularly used the women’s locker room throughout their careers and after their retirements, intended to sue the West Virginia state police after media reported on the alleged hidden camera, according to the letter reviewed by the Guardian.

On 16 June, in her fourth and final notice of legal action, Toriseva revealed that her law office has gone from representing three women to 67, all of whom will be “filing claims against the West Virginia State Police for creating a toxic and hostile environment”.

In addition to the dozens of women who attended or visited the academy from 1994 to the present day, there were at least 10 minors likely between the ages of 14 and 17 who were part of the state police’s Junior Trooper academy and used the locker room, the letter said.

from the past: wasting money on incompetence!!!

Research shows that arrests for serious crimes are quite rare.

Police solve just 2% of all major crimes

BLAKE NISSEN - the conversation

Published: August 20, 2020 8.18am EDT

As Americans across the nation protest police violence, people have begun to call for cuts or changes in public spending on police. But neither these nor other proposed reforms address a key problem with solving crimes.

My recent review of 50 years of national crime data confirms that, as police report, they don’t solve most serious crimes in America. But the real statistics are worse than police data show. In the U.S. it’s rare that a crime report leads to police arresting a suspect who is then convicted of the crime.

The data show that consistently over the decades, fewer than half of serious crimes are reported to police. Few, if any arrests are made in those cases.

In reality, about 11% of all serious crimes result in an arrest, and about 2% end in a conviction. Therefore, the number of people police hold accountable for crimes – what I call the “criminal accountability” rate – is very low.

Many crimes aren’t reported

Police can only work on solving crimes they are aware of, and can only report statistics about their work based on criminal behavior they know about. But there is a huge slice of crime police never find out about.

By comparing surveys of the public with police reports, it’s clear that less than half of serious violent felonies – crimes like aggravated assault and burglary – ever get reported to the police.

Real arrest rates

In 2018, the rate of arrest for serious felony crimes reported to police was about 22%. But because twice as many crimes happen as the police are told about, the arrest rate for all crimes that happened was half what police reported – just 11%.

Real conviction rates

The official percentage of serious crimes where a person is actually convicted is even lower, though data is hard to confirm. The Bureau of Justice Statistics has not reported national conviction rates for serious crimes since 2006 – but in that year, out of all serious crimes reported to the police, only 4.1% of cases ended with an individual convicted in the wake of a reported crime.

Again, taking into account the fact that twice as many crimes happen, the national conviction rate in 2006 was actually closer to 2%.

Resolving crimes without arrests

There are ways police resolve conflicts and crimes without arresting people – for instance, by mediating neighborhood disputes and directing wayward young people to social services and community programs. But so long as police departments measure success by arrests, that won’t happen more widely.

When considering approaches to police reform, it’s important to remember that Americans still don’t report about half of major crimes – and police don’t solve very many of the cases that do get reported. Truly improving policing will require addressing these two gaps.

My recent review of 50 years of national crime data confirms that, as police report, they don’t solve most serious crimes in America. But the real statistics are worse than police data show. In the U.S. it’s rare that a crime report leads to police arresting a suspect who is then convicted of the crime.

The data show that consistently over the decades, fewer than half of serious crimes are reported to police. Few, if any arrests are made in those cases.

In reality, about 11% of all serious crimes result in an arrest, and about 2% end in a conviction. Therefore, the number of people police hold accountable for crimes – what I call the “criminal accountability” rate – is very low.

Many crimes aren’t reported

Police can only work on solving crimes they are aware of, and can only report statistics about their work based on criminal behavior they know about. But there is a huge slice of crime police never find out about.

By comparing surveys of the public with police reports, it’s clear that less than half of serious violent felonies – crimes like aggravated assault and burglary – ever get reported to the police.

Real arrest rates

In 2018, the rate of arrest for serious felony crimes reported to police was about 22%. But because twice as many crimes happen as the police are told about, the arrest rate for all crimes that happened was half what police reported – just 11%.

Real conviction rates

The official percentage of serious crimes where a person is actually convicted is even lower, though data is hard to confirm. The Bureau of Justice Statistics has not reported national conviction rates for serious crimes since 2006 – but in that year, out of all serious crimes reported to the police, only 4.1% of cases ended with an individual convicted in the wake of a reported crime.

Again, taking into account the fact that twice as many crimes happen, the national conviction rate in 2006 was actually closer to 2%.

Resolving crimes without arrests

There are ways police resolve conflicts and crimes without arresting people – for instance, by mediating neighborhood disputes and directing wayward young people to social services and community programs. But so long as police departments measure success by arrests, that won’t happen more widely.

When considering approaches to police reform, it’s important to remember that Americans still don’t report about half of major crimes – and police don’t solve very many of the cases that do get reported. Truly improving policing will require addressing these two gaps.

Police rip Black man's prosthetic leg off during violent traffic stop: 'It's like someone ripping off your skin'

Sky Palma - RAW STORY

February 15, 2022

A New York man with a prosthetic leg is seeking millions in damages from the Suffolk County Police Department, saying he was wrongfully arrested and injured by officers. He also claims officers ripped off his leg and threw it in the trunk of a police cruiser, NBC New York reports.

Waverly Lucas says he was pulled over by officers who demanded his identification and accused him of public urination. Lucas refused to provide his ID and began recording the incident on Facebook Live. That's when he said police assaulted him while trying to detain him.

"To rip that off, it's like someone ripping off your skin," Lucas said, speaking of his prosthetic leg. "Because it's like it's almost glued to my skin."

According to Lucas's attorney, the only explanation for him being pulled over is the fact that he's Black.

Waverly Lucas says he was pulled over by officers who demanded his identification and accused him of public urination. Lucas refused to provide his ID and began recording the incident on Facebook Live. That's when he said police assaulted him while trying to detain him.

"To rip that off, it's like someone ripping off your skin," Lucas said, speaking of his prosthetic leg. "Because it's like it's almost glued to my skin."

According to Lucas's attorney, the only explanation for him being pulled over is the fact that he's Black.

Historian: Black distrust of the police is about more than acts of violence

History News Network

November 08, 2021

We're supposed to be living in a time of racial reckoning. After the world watched George Floyd's excruciating street execution, over and over, there emerged a groundswell of support for antiracist work throughout society in the spring and summer of 2020. Reforming policing and reining in its obvious excesses became one of the most immediate goals.

In the last place that George Floyd called home, a majority of Minneapolis City Council members initially pledged, loudly, to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department, which turned into a modest budget cut. Disappointed activists put the question of replacing the police department with a department of public safety to voters this Election Day, and it failed. A yearlong, bipartisan police reform effort in Congress collapsed, producing nothing at all. Various states and localities have implemented reforms, such as limiting chokeholds or making police complaints publicly available, almost singularly focused on reducing violence and death at the hands of police.

This makes perfect sense, especially given the prevalence of these deaths caught on video in recent years, and the stark horror of watching people lose their lives, often in circumstances that are questionable, at best. However, policing's racial problem is age-old, and goes well beyond physical violence as I document in my new study of structural racism in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, The Harlem Uprising - Segregation and Inequality in Postwar New York City. If we don't understand the history, we miss the long legacy of distrust that people of color, particularly Black people, feel toward the police. And beginning and ending at beatings and shootings leaves us with a severely incomplete understanding of what is and has been wrong.

In July, a white NYPD lieutenant, with nearly two decades on the job and well over a dozen commendations for outstanding police work, including four for disarming men with guns, shot and killed a fifteen-year-old Black boy. He said the youngster came at him with a knife, even when the officer announced himself, even after he shot the boy the first time. Witnesses disputed the officer's account, and there was no video. A grand jury declined to indict the lieutenant, and the department ruled the shooting justified.

You may have heard about this one, but probably not, because it was in 1964. The boy was James Powell, Thomas Gilligan his killer. As for who believed this story, the New York Amsterdam News, the city's oldest Black newspaper wrote that "Nobody in Harlem does." In 1964, that was understood to mean Black New Yorkers did not trust the NYPD's version of events. They had little reason to.

The NYPD in the mid-1960s was thoroughly corrupt, racist and violent. Officers, individually and collectively, reserved their worst behavior for the city's segregated Black neighborhoods, like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville. Taking bribes from building contractors, tow truck drivers, funeral directors and defense lawyers was as much a part of the job as clocking in. They ran protection rackets on sex traffickers and heroin dealers, generating substantial weekly payments that would be split among the men working these patrols, and required local businesses to pay smaller amounts, which would be divvied up and spread around the local precinct. To anyone skeptical, read the Knapp Commission's report.

Police in the city treated Black neighborhoods, especially Harlem, as crime reservations, containment areas for drugs, gambling and sex work. It's not that the NYPD, from rank-and-file high up into the executive corps, permitted these illicit industries to exist. Instead, they worked hard to make sure these outlets of misery and ruin flourished, both out of selfish financial motives and racial spite, given that the NYPD was 95 percent white. Multiple memoirs from men on the force during this time establish that they worked with "a deep sea of racism and bitterness, poison and untamed cruelty in our souls."

And yes, the police were also violent, ranging from arbitrary roughness on the street, to sadistic squad room beatings, to shootings. Of course Black New Yorkers opposed this. But they also wanted safer communities, which the NYPD assiduously denied them. They had to live with all manner of random street crime, especially that which is concomitant with an impoverished neighborhood rife with addiction. More policing and less police violence and discourtesy are not mutually exclusive, or at least they should not be.

Some of this behavior has changed. It is much more difficult for police departments today to be so outwardly corrupt that they effectively act as untouchable criminal organizations. But many aspects remain. Police departments across the country have long used drivers as ATMs to fund local budgets, frequently targeting Black motorists for heightened enforcement of minor traffic laws. Not only do these stops engender bitterness, but the resulting fines also threaten to financially ruin people already living on the edge, and too often escalate into totally unnecessary shows of force. Ticket and arrest quotas demand that people be brought into the criminal justice system without good reason.

The racist assumption that Black and Brown men are more likely to be up to no good led to the explosion of stop-and-frisk in New York City, a practice the state approved in 1965. For decades, the police practiced the on-street search of someone who aroused an officer's suspicion, including "furtive movements" or simply being in a location with a high crime rate. The number of these searches peaked at 685,724 in 2011. Since 2014, the department instructed officers to only detain people when they have a strong suspicion of criminal activity, and the numbers dropped into the five-figure range.

For the last two decades, ninety percent of those officers detained were Black or Latinx, though the city is about 45 percent white. Ninety percent were released, having been found not engaging in or possessing anything illegal. Put another way, the NYPD was stopping and frisking tens of to hundreds of thousands of people, every year, who were doing nothing illegal. There is no evidence the practice measurably reduces crime.

The police also lie, from the smallest to the direst of matters, and courts side disproportionately with an officer's word. Officer Michael Slager of North Charleston, South Carolina, said he feared for his life because Walter Scott had taken his Taser and Slager "felt threatened." In reality, Slager had tased Scott after a physical altercation; Scott then ran away, unarmed, and Slager shot him in the back five times, killing him. But again, this is just a recent example of a very old practice, and perhaps one of the worst examples of a "cover charge," or a false accusation after the fact that permits officers to brutalize and arrest or kill someone. If the victim survives and complains, who believes an alleged felon?

Policing has been in need of reform since its inception. Changes have come, but they've been slow, and significant numbers of people, disproportionately Black and Brown, have experienced and continue to experience discourtesy, bigotry, false allegations, and violence. The outrage we saw explode in 2020 shouldn't have surprised anyone. If anything, we should be surprised the streets of America had been so quiet before.

People of color, and Black people in particular, have always experienced justice differently in this country. Distrust toward the police is multigenerational, and not the result of one violent act, or Marxist agitation, or exposure to rap lyrics. Until we fundamentally reimagine what policing looks like in this country, this situation seems unlikely to change.

In the last place that George Floyd called home, a majority of Minneapolis City Council members initially pledged, loudly, to dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department, which turned into a modest budget cut. Disappointed activists put the question of replacing the police department with a department of public safety to voters this Election Day, and it failed. A yearlong, bipartisan police reform effort in Congress collapsed, producing nothing at all. Various states and localities have implemented reforms, such as limiting chokeholds or making police complaints publicly available, almost singularly focused on reducing violence and death at the hands of police.

This makes perfect sense, especially given the prevalence of these deaths caught on video in recent years, and the stark horror of watching people lose their lives, often in circumstances that are questionable, at best. However, policing's racial problem is age-old, and goes well beyond physical violence as I document in my new study of structural racism in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, The Harlem Uprising - Segregation and Inequality in Postwar New York City. If we don't understand the history, we miss the long legacy of distrust that people of color, particularly Black people, feel toward the police. And beginning and ending at beatings and shootings leaves us with a severely incomplete understanding of what is and has been wrong.

In July, a white NYPD lieutenant, with nearly two decades on the job and well over a dozen commendations for outstanding police work, including four for disarming men with guns, shot and killed a fifteen-year-old Black boy. He said the youngster came at him with a knife, even when the officer announced himself, even after he shot the boy the first time. Witnesses disputed the officer's account, and there was no video. A grand jury declined to indict the lieutenant, and the department ruled the shooting justified.

You may have heard about this one, but probably not, because it was in 1964. The boy was James Powell, Thomas Gilligan his killer. As for who believed this story, the New York Amsterdam News, the city's oldest Black newspaper wrote that "Nobody in Harlem does." In 1964, that was understood to mean Black New Yorkers did not trust the NYPD's version of events. They had little reason to.

The NYPD in the mid-1960s was thoroughly corrupt, racist and violent. Officers, individually and collectively, reserved their worst behavior for the city's segregated Black neighborhoods, like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville. Taking bribes from building contractors, tow truck drivers, funeral directors and defense lawyers was as much a part of the job as clocking in. They ran protection rackets on sex traffickers and heroin dealers, generating substantial weekly payments that would be split among the men working these patrols, and required local businesses to pay smaller amounts, which would be divvied up and spread around the local precinct. To anyone skeptical, read the Knapp Commission's report.

Police in the city treated Black neighborhoods, especially Harlem, as crime reservations, containment areas for drugs, gambling and sex work. It's not that the NYPD, from rank-and-file high up into the executive corps, permitted these illicit industries to exist. Instead, they worked hard to make sure these outlets of misery and ruin flourished, both out of selfish financial motives and racial spite, given that the NYPD was 95 percent white. Multiple memoirs from men on the force during this time establish that they worked with "a deep sea of racism and bitterness, poison and untamed cruelty in our souls."

And yes, the police were also violent, ranging from arbitrary roughness on the street, to sadistic squad room beatings, to shootings. Of course Black New Yorkers opposed this. But they also wanted safer communities, which the NYPD assiduously denied them. They had to live with all manner of random street crime, especially that which is concomitant with an impoverished neighborhood rife with addiction. More policing and less police violence and discourtesy are not mutually exclusive, or at least they should not be.

Some of this behavior has changed. It is much more difficult for police departments today to be so outwardly corrupt that they effectively act as untouchable criminal organizations. But many aspects remain. Police departments across the country have long used drivers as ATMs to fund local budgets, frequently targeting Black motorists for heightened enforcement of minor traffic laws. Not only do these stops engender bitterness, but the resulting fines also threaten to financially ruin people already living on the edge, and too often escalate into totally unnecessary shows of force. Ticket and arrest quotas demand that people be brought into the criminal justice system without good reason.

The racist assumption that Black and Brown men are more likely to be up to no good led to the explosion of stop-and-frisk in New York City, a practice the state approved in 1965. For decades, the police practiced the on-street search of someone who aroused an officer's suspicion, including "furtive movements" or simply being in a location with a high crime rate. The number of these searches peaked at 685,724 in 2011. Since 2014, the department instructed officers to only detain people when they have a strong suspicion of criminal activity, and the numbers dropped into the five-figure range.

For the last two decades, ninety percent of those officers detained were Black or Latinx, though the city is about 45 percent white. Ninety percent were released, having been found not engaging in or possessing anything illegal. Put another way, the NYPD was stopping and frisking tens of to hundreds of thousands of people, every year, who were doing nothing illegal. There is no evidence the practice measurably reduces crime.

The police also lie, from the smallest to the direst of matters, and courts side disproportionately with an officer's word. Officer Michael Slager of North Charleston, South Carolina, said he feared for his life because Walter Scott had taken his Taser and Slager "felt threatened." In reality, Slager had tased Scott after a physical altercation; Scott then ran away, unarmed, and Slager shot him in the back five times, killing him. But again, this is just a recent example of a very old practice, and perhaps one of the worst examples of a "cover charge," or a false accusation after the fact that permits officers to brutalize and arrest or kill someone. If the victim survives and complains, who believes an alleged felon?

Policing has been in need of reform since its inception. Changes have come, but they've been slow, and significant numbers of people, disproportionately Black and Brown, have experienced and continue to experience discourtesy, bigotry, false allegations, and violence. The outrage we saw explode in 2020 shouldn't have surprised anyone. If anything, we should be surprised the streets of America had been so quiet before.

People of color, and Black people in particular, have always experienced justice differently in this country. Distrust toward the police is multigenerational, and not the result of one violent act, or Marxist agitation, or exposure to rap lyrics. Until we fundamentally reimagine what policing looks like in this country, this situation seems unlikely to change.

‘In a Defenseless Position’: South Carolina Cop Charged After Stomping Black Man’s Head Into Concrete Thanks to 911 Caller Mistaking the Man’s Stick for a Weapon

Niara Savage | atlanta black star

August 7, 2021

The South Carolina officer filmed stomping a Black man’s head into concrete in late July has been fired and charged with first-degree assault and battery, according to the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division.

Orangeburg Department of Public Safety Officer David Lance Dukes, 38, was fired after internal officials reviewed body camera footage of the July 26 incident, during which Dukes stomped 58-year-old Clarence Gailyard’s head while the man was on his hands and knees.

“Every time I look in the mirror, I see the scar on my forehead, and it’s not OK. The only thing I want the community to do is change,” Gailyard said Tuesday alongside his attorney Justin Bamberg.

On July 26, Gailyard was walking with his stick that he carries in case a dog approaches him. He also walks with a cane often and often moves slowly as a result of pins and rods in his leg from being hit by a vehicle on a bicycle, Bamberg said.

Someone called 911 thinking the stick Gailyard was holding was a gun. Dukes arrived and ordered Gailyard to the ground but the man wasn’t physically able to immediately comply. While he was on his hands and knees, Dukes stomped Gailyard’s head, causing it to hit the concrete.

“Officer Dukes then approached the victim, who was on his hands and knees. While the victim was in a defenseless position on his hands and knees, Officer Dukes raised his right leg and forcibly stomped with his boot on the victim’s neck and/or head area. The force of the blow caused the victim’s head to strike the concrete. The victim suffered a contusion to his forehead and was transported by EMS,” says a warrant from the state law enforcement division.

Bamberg released an eight-second video of the incident taken by a bystander, as well as body camera footage, which was played during the press conference. Dukes was fired two days after the incident, then charged days later.

The body camera footage is from another officer on the scene and shows the aftermath of the incident.

“You threw me down!” Gailyard said.

“I sure did,” Dukes replied. “You wasn’t listening.”

Officer Aqkwele Polidore, who was also on the scene, spoke up and told a sergeant who arrived later that Gailyard was lying about what had happened. Body camera footage shows Dukes speaking to a sergeant about what happened, leaving out the part about him striking Gailyard with his foot. Polidore told the sergeant that she’d seen Dukes strike Gailyard as she pulled up to the scene.

“She deserves a commendation,” Bamberg said.

Dukes was fired from another police department, the Calhoun County Sheriff’s Office in October due to insubordination, according to The Times and Democrat of Orangeburg.

On Saturday, a judge set Dukes’ bond at $10,000. While out on bond he is not permitted to posses firearms. If convicted, he faces 10 years in prison.

Bamberg tweeted a photo of his client showing his head wrapped with gauze over the wound. He tweeted, “This is my client, Mr. Clarence. Disabled, completely innocent bystander, unarmed, and defenseless. Got his head STOMPED on by a now fired officer in Orangeburg who repeatedly used excessive force on the people. Was also fired by his previous agency < a year ago. We can do better”

Orangeburg Department of Public Safety Officer David Lance Dukes, 38, was fired after internal officials reviewed body camera footage of the July 26 incident, during which Dukes stomped 58-year-old Clarence Gailyard’s head while the man was on his hands and knees.

“Every time I look in the mirror, I see the scar on my forehead, and it’s not OK. The only thing I want the community to do is change,” Gailyard said Tuesday alongside his attorney Justin Bamberg.

On July 26, Gailyard was walking with his stick that he carries in case a dog approaches him. He also walks with a cane often and often moves slowly as a result of pins and rods in his leg from being hit by a vehicle on a bicycle, Bamberg said.

Someone called 911 thinking the stick Gailyard was holding was a gun. Dukes arrived and ordered Gailyard to the ground but the man wasn’t physically able to immediately comply. While he was on his hands and knees, Dukes stomped Gailyard’s head, causing it to hit the concrete.

“Officer Dukes then approached the victim, who was on his hands and knees. While the victim was in a defenseless position on his hands and knees, Officer Dukes raised his right leg and forcibly stomped with his boot on the victim’s neck and/or head area. The force of the blow caused the victim’s head to strike the concrete. The victim suffered a contusion to his forehead and was transported by EMS,” says a warrant from the state law enforcement division.

Bamberg released an eight-second video of the incident taken by a bystander, as well as body camera footage, which was played during the press conference. Dukes was fired two days after the incident, then charged days later.

The body camera footage is from another officer on the scene and shows the aftermath of the incident.

“You threw me down!” Gailyard said.

“I sure did,” Dukes replied. “You wasn’t listening.”

Officer Aqkwele Polidore, who was also on the scene, spoke up and told a sergeant who arrived later that Gailyard was lying about what had happened. Body camera footage shows Dukes speaking to a sergeant about what happened, leaving out the part about him striking Gailyard with his foot. Polidore told the sergeant that she’d seen Dukes strike Gailyard as she pulled up to the scene.

“She deserves a commendation,” Bamberg said.

Dukes was fired from another police department, the Calhoun County Sheriff’s Office in October due to insubordination, according to The Times and Democrat of Orangeburg.

On Saturday, a judge set Dukes’ bond at $10,000. While out on bond he is not permitted to posses firearms. If convicted, he faces 10 years in prison.

Bamberg tweeted a photo of his client showing his head wrapped with gauze over the wound. He tweeted, “This is my client, Mr. Clarence. Disabled, completely innocent bystander, unarmed, and defenseless. Got his head STOMPED on by a now fired officer in Orangeburg who repeatedly used excessive force on the people. Was also fired by his previous agency < a year ago. We can do better”

5 police officers face criminal charges in hotel beating of Black men

By BILL HUTCHINSON - abc news

Wednesday, August 4, 2021

Five Miami Beach police officers are now facing criminal charges after they were seen on body camera and security video kicking a handcuffed Black man in a hotel lobby and tackling and pummeling a Black witness who was recording the incident on his cellphone.

Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle announced the officers have been suspended and charged with first-degree misdemeanor battery.

"Excessive force can never, ever, ever be an acceptable foundation for policing in any community," Fernandez Rundle said at a news conference on Monday. "Officers who forget that fact do a grave disservice to the people they have sworn to serve."

Fernandez Rundle, with Miami Beach Police Chief Richard Clements standing behind her, played a four-minute compilation of body camera and security camera footage showing the episode that unfolded in the early hours of July 26 in the lobby of the Royal Palm Hotel in South Beach.

The state attorney went over the footage in detail, stopping and rewinding it several times to point out the individual officers who were charged and even running the video in slow motion to show two officers kicking the handcuffed detainee in the head.

"With my team, when we saw that kick to the head, and then we replayed it and saw all the kicks that preceded it -- it was just unfathomable. It was unspeakable. It was just inexcusable," Fernandez Rundle said.

She said the incident started when a police officer chased 24-year-old Dalonta Crudup into the hotel and stopped him at gunpoint as he tried to take an elevator.

A police report obtained by Miami ABC affiliate WPLG alleged that Crudup was involved in a confrontation with a Miami Beach bicycle police officer over illegally parking a motorized scooter and allegedly struck the officer with the scooter. Fernandez Rundle said the officer's leg was injured in the encounter with Crudup and that he had to be hospitalized.

Once stopped by a police lieutenant inside the hotel, security camera footage showed Crudup appearing to comply with the officer's orders to step out of an elevator with his hands up.

"Crudup exits the elevator with his hands raised and drops down to the ground with his arms outstretched in front of him," Fernandez Rundle said.

After he was handcuffed with his arms behind his back, the security video showed 21 officers rushing into the lobby, swarming around Crudup and assisting in his arrest, Fernandez Rundle said.

"It is at this point the situation begins to change, in our opinion, from a legitimate arrest of a criminal suspect into an ongoing investigation of the use of force by five Miami Beach police officers," Fernandez Rundle said.

The security video appeared to show Sgt. Jose Perez allegedly kick Crudup in the head while he was face down on the ground with other officers on top of him. At one point, Perez appears to also be seen in the video lifting Crudup and slamming him to the ground.

The video showed Perez walk away briefly twice before returning and appearing to kick Crudup in the head.

The hotel security video allegedly showed Officer Kevin Perez, who Fernandez Rundle said is not related to Jose Perez, kicking Crudup at least four times.

Other officers then turned their attention to 28-year-old Khalid Vaughn, who Fernandez Rundle said was standing 12 to 15 feet away recording Crudup's arrest.

Body camera video appeared to show officers Robert Sabater allegedly tackling Vaughn, who was backing away. Officers David Rivas and Steven Serrano allegedly helped Sabater pin Vaughn against a concrete pillar. The body camera video appears to show Sabarter, Rivas and Serrano taking turns pummeling Vaughn with body blows.

"Body-worn cameras played a critical role in this case," Fernandez Rundle said.

She said Vaughn was initially arrested on charges of impeding, provoking and harassing officers. Fernandez Rundle said those charges were dropped as soon after she viewed the videos.

She said the investigation is ongoing and the officers could face more charges.

Fernandez Rundle praised Clements for taking swift action and immediately informing her office of the incident.

"This is by no means at all a reflection of the dedicated men and women of the Miami Beach Police Department," Clements said at Monday's news conference. "Moving forward, I can tell you that my staff and I promise you, as individuals and as an agency, that we will learn from this. And we will grow from this."

Upon his release from custody, Crudup told WPLG, "I got beat up, I got stitches, went to the hospital." He denied parking the scooter illegally and striking the officer with it.

Vaughn told WPLG he started video recording the incident after Crudup was already handcuffed and on the ground.

"They beat him, turned around, charged me down, beat me ... punched me, elbowed me in the face," Vaughn told WPLG. "I literally got jumped by officers."

Paul Ozeata, president of the Fraternal Order of Police, told the Miami Herald that the five charged officers are being represented by the police union's attorneys. He told the newspaper that he hadn't viewed the video evidence close enough to comment on the officers' actions.

"They deserve their day in court, just as everyone else does," Ozeata said.

In an interview with ABC News Live Prime anchor Linsey Davis, Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber said he viewed the video footage and called the incident "unacceptable in every way."

"This is not who our department is," Gelber said, adding, "And what our department did was exactly the right thing they should do, which is relieved the officers of duty immediately, and then within hours refer the entire matter to the state attorney's office for a review."

Miami-Dade State Attorney Katherine Fernandez Rundle announced the officers have been suspended and charged with first-degree misdemeanor battery.

"Excessive force can never, ever, ever be an acceptable foundation for policing in any community," Fernandez Rundle said at a news conference on Monday. "Officers who forget that fact do a grave disservice to the people they have sworn to serve."

Fernandez Rundle, with Miami Beach Police Chief Richard Clements standing behind her, played a four-minute compilation of body camera and security camera footage showing the episode that unfolded in the early hours of July 26 in the lobby of the Royal Palm Hotel in South Beach.

The state attorney went over the footage in detail, stopping and rewinding it several times to point out the individual officers who were charged and even running the video in slow motion to show two officers kicking the handcuffed detainee in the head.

"With my team, when we saw that kick to the head, and then we replayed it and saw all the kicks that preceded it -- it was just unfathomable. It was unspeakable. It was just inexcusable," Fernandez Rundle said.

She said the incident started when a police officer chased 24-year-old Dalonta Crudup into the hotel and stopped him at gunpoint as he tried to take an elevator.

A police report obtained by Miami ABC affiliate WPLG alleged that Crudup was involved in a confrontation with a Miami Beach bicycle police officer over illegally parking a motorized scooter and allegedly struck the officer with the scooter. Fernandez Rundle said the officer's leg was injured in the encounter with Crudup and that he had to be hospitalized.

Once stopped by a police lieutenant inside the hotel, security camera footage showed Crudup appearing to comply with the officer's orders to step out of an elevator with his hands up.

"Crudup exits the elevator with his hands raised and drops down to the ground with his arms outstretched in front of him," Fernandez Rundle said.

After he was handcuffed with his arms behind his back, the security video showed 21 officers rushing into the lobby, swarming around Crudup and assisting in his arrest, Fernandez Rundle said.

"It is at this point the situation begins to change, in our opinion, from a legitimate arrest of a criminal suspect into an ongoing investigation of the use of force by five Miami Beach police officers," Fernandez Rundle said.

The security video appeared to show Sgt. Jose Perez allegedly kick Crudup in the head while he was face down on the ground with other officers on top of him. At one point, Perez appears to also be seen in the video lifting Crudup and slamming him to the ground.

The video showed Perez walk away briefly twice before returning and appearing to kick Crudup in the head.

The hotel security video allegedly showed Officer Kevin Perez, who Fernandez Rundle said is not related to Jose Perez, kicking Crudup at least four times.

Other officers then turned their attention to 28-year-old Khalid Vaughn, who Fernandez Rundle said was standing 12 to 15 feet away recording Crudup's arrest.

Body camera video appeared to show officers Robert Sabater allegedly tackling Vaughn, who was backing away. Officers David Rivas and Steven Serrano allegedly helped Sabater pin Vaughn against a concrete pillar. The body camera video appears to show Sabarter, Rivas and Serrano taking turns pummeling Vaughn with body blows.

"Body-worn cameras played a critical role in this case," Fernandez Rundle said.

She said Vaughn was initially arrested on charges of impeding, provoking and harassing officers. Fernandez Rundle said those charges were dropped as soon after she viewed the videos.

She said the investigation is ongoing and the officers could face more charges.

Fernandez Rundle praised Clements for taking swift action and immediately informing her office of the incident.

"This is by no means at all a reflection of the dedicated men and women of the Miami Beach Police Department," Clements said at Monday's news conference. "Moving forward, I can tell you that my staff and I promise you, as individuals and as an agency, that we will learn from this. And we will grow from this."

Upon his release from custody, Crudup told WPLG, "I got beat up, I got stitches, went to the hospital." He denied parking the scooter illegally and striking the officer with it.

Vaughn told WPLG he started video recording the incident after Crudup was already handcuffed and on the ground.

"They beat him, turned around, charged me down, beat me ... punched me, elbowed me in the face," Vaughn told WPLG. "I literally got jumped by officers."

Paul Ozeata, president of the Fraternal Order of Police, told the Miami Herald that the five charged officers are being represented by the police union's attorneys. He told the newspaper that he hadn't viewed the video evidence close enough to comment on the officers' actions.

"They deserve their day in court, just as everyone else does," Ozeata said.

In an interview with ABC News Live Prime anchor Linsey Davis, Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber said he viewed the video footage and called the incident "unacceptable in every way."

"This is not who our department is," Gelber said, adding, "And what our department did was exactly the right thing they should do, which is relieved the officers of duty immediately, and then within hours refer the entire matter to the state attorney's office for a review."

New Report Finds Police-Perpetrated Killings in 2020 Were Vastly Underreported

BY James Dennis Hoff, Left Voice

PUBLISHED June 4, 2021

According to The Guardian newspaper, 1,093 people were killed by police in the United States in 2020. Meanwhile, the website Mapping Police Violence, another well-respected source for such information, puts that number slightly higher at 1,127, and Statista claims it is 1,021. These figures reflect a consensus that has existed since around 2015 that, in general, police in the United States kill about 1,000 people per year.

This extraordinary number far exceeds that of any other wealthy country in the world. For instance, police in the United States kill 10 times the number of people per capita as those in France, 30 times those in Germany, and 60 times more than those killed in the UK. Since 2000, it is estimated that tens of thousands of people, including at least 8,000 Black people, were killed by U.S. police and more are killed almost every day. In fact, since the beginning of 2021, there have been only six days in which the police did not shoot, asphyxiate, beat to death, or otherwise kill someone.

As shocking as the numbers are, activists and critics of police violence have long believed that the actual number of people killed by police in the United States was likely much higher. And now, a new report published by the Raza Database Project at California State University, Santa Barbara (CSUSB), is challenging the 1,000-per-year narrative.

The Raza Database Project is a product of the Latino Education and Advocacy Days Group at CSUSB. To complete the database, the group enrolled more than 50 volunteer researchers, journalists, and family members of people killed by police violence to research and investigate what they suspected was a significant undercount of Black and Latino people killed by the police.

The report, which was released on May 27, shows that there has in fact been a massive undercount of police killings, particularly among Black and Latino people. The greatest number of these new deaths come from people who died while already in police custody, including many who had been falsely listed as having died from “medical emergencies.” This research shows that the number of people killed by police in the United States is likely almost double what is normally reported by the media.

According to the report, the actual number of police killings for 2020 was 2,134 — well over a thousand more than what The Guardian reported for that same year. And that same discrepancy is seen in almost all the data every year since 2014. The project also shows that the number of Latino people killed by the police has also been significantly underreported, in large part because many police departments rely heavily on surnames to classify the race or ethnicity of people in their custody.

As a result of this, the actual number of Latino people killed by police is actually about 25 percent higher than normally reported, according to the project. Meanwhile, a closer inspection of the number of victims whose ethnicity was listed as “unknown” revealed that the number of Asians and Pacific Islanders killed by Police increased by an astonishing 600 percent, from 217 to more than 1,400 since just 2014.

These numbers show that police across the United States are killing significantly more people than previously thought, and many more people of color across a much wider spectrum of ethnicities. And these numbers held steady despite a mass uprising against police violence.